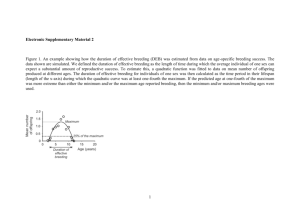

tc8_25_review_non_native_species_0

advertisement