Introduction - Green Evangelist

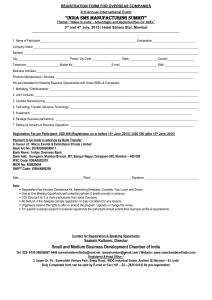

advertisement

ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE - SHIFT FROM COMMAND AND CONTROL MECHANISM TO MARKET DRIVEN STRATEGIES Dr.Smt.Bala Krishnamoorthy, Associate Professor, Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies–Deemed University, India balak@nmims.edu, balakrish_8@hotmail.com Abstract: Sustainability is the central theme in almost anything one would like to interrelate in environmental management at local, regional and at global levels. The right to development must be fulfilled equitably so that the developmental and environmental needs of present and future generations can be met. Management of environmental issues in different secotrs is shifting focus from mere regulations to adopting different approached of market driven strategies like ISO certification, Eco labeling, Voluntary reporting practices, Total Quality Environmental Management, Life Cycle Assessment etc. This paper takes a closer look at the emerging trends among the market driven strategies. The extent to which these strategies would enlist the participation of the different beneficiaries in the environmental resource group is yet to be fully developed. However, the shift from command and control approach is clearly visible. Introduction Sustainability is the central theme in almost anything one would like to interrelate in environmental management at local, regional and at global levels. The right to development must be fulfilled equitably so that the developmental and environmental needs of present and future generations can be met. This paper on shifting focus from command and control mechanism to market driven strategies also salutes the all encompassing concept of sustainability The Agenda 21 gives us the focus for all conscious efforts to manage environmental issues in all the different sectors. Principle 2 of Agenda 21 states “Human beings are at the center of concerns for sustainable development. They are entitled to a healthy and productive life in harmony with nature.” It is indeed this thought, which serves as a driving force to look at alternatives, more effective and less time consuming to address the multifaceted environmental issues. The interest in environmental issues and developing and managing the coping mechanisms at the individual, group, and the national levels has undergone a sea of change in the past few decades. The impact of industrial activity on the environment was nothing new to the twentieth century. As a part of the attempts were made to combat the effects of London’s blanket smogs, the term acid rain was invented in the nineteenth century, by Britain’s first chief Alkali Inspector, In 1950s the Britain introduced first environmental legislations in the form of Clean Air Acts. Rachel Carson’s silent spring written during the year 1962 remains the most eloquently written scientific text on the vulnerability of nature to organic pesticides made from chlorinated hydrocarbons. It inspired millions to gain environmental consciousness on a global scale of the dangers of manufacture and use of toxic substances. Murry Bookchin (1962) our synthetic Environment also noted the pollution of the natural world and its impact on human health and society. In 1969 in the United States, the National Environmental Policy Act established the Environmental protection Agency. The world’s first green party emerged in New Zealand as the Values Party. In 1970s, a group of industrialists led by Dr.Aureio Peccei worked with Massachusetts Institute of technology to produce computer projections of the future ecological impacts in five fields of human activity namely population, agricultural production, natural resource use, industrial production, and pollution. The club of Rome report, “The limits of growth (Meadows et al 1972) was the first attempt at a systematic assessment of the global impact of industrial progress and development. Throughout 1970s and 1980s fuelled by the oil price rises of 1973-4 and 1979-80s resource issues dominated economic and political discussions. The ecologist in 1972 published, “A Blue print for survival outlined the un sustainability of human numbers and percapita consumption” In 1974 World Watch Institute was established to propagate research in environmental issues. In 1978, Germany introduced the Blue Angel Award scheme based on the environmental emblem of the United Nations. In 1985, Myers wrote the Gaia Atlas of Planet Man. During 1987, the Brundtland Report popularly known as Our Common Future provided the impetus required to integrate the efforts towards sustainability all over the world. The decade 1985 –1995 has demonstrated that environmental excellence is synonymous with both competitive and cooperative advantage in the market place. The environment is no longer a threat to the industry, but an opportunity. It is as much in the interest of the industry as the environment, to have a well-balanced and sustained economic and social system. The levels of interests and the priorities for tackling environmental issues have not always been uniform. The industrialized countries have by and large been the trendsetter for providing the institutionalized support framework for tackling the environmental issues and formally identifying the major stakeholders and the interested parties. The developing countries tried to push back the environmental agenda as much as possible giving the reason as that it is indeed the industrialized countries which are using far too large part of the so called environmental resources so it is only fair that they clean the back yard. It was not until much later that the realization that it is one global unit that we all share and what happen at one part of the globe will invariably affect others in all other parts prevailed into their mindsets and the attitudes. A lot of credit for disseminating this information and knowledge goes to the global environmental bodies like UNEP and the Global conventions which were active to spread awareness and bring about consensus in the decision making processes. Though trade related environmental issues are still debated without arriving at amicable solutions it is true that the environmental agenda (environmental lobbying) is looked upon at least in the developing world as the hidden agenda, which comes up with the vested interest. This interplay of “who wins ultimately?” among the nations big and small brought about the new interest areas both academically and for the society on environmental justice, environmental ethical dilemmas, green trade wars, environmental refugees due tot unplanned development activities and the questions of relative good for every one. A company as a representative social institution of our society in addition to being an economic tool is a political and social body, its social function to the community is as important as its economic function as an effective producer. (Drucker, P. (1964) The concept of the corporation, New York, Mentor p132. ) It is important to realize that the company is a public institution and just not a private arrangement created by a contract. Sometimes the political and social contract can become deterministic in shaping its destiny than the economic factors. The new politics of corporate governance is about balancing economic performance against social accountability. Companies have adopted environmental policies for a number of reasons. According to Francis Cairncoss (1995:179) these include 1.Management morale, it can be advantageous and improve general management morale, to have an environmental policy in which pride can be taken. 2.Staff morale, pressure to adopt environmental policies has often come from a firm’s staff. 3.Consumer pressure, often consumers want to know more about the origins of the goods they buy. 4. Desire for publicity and a good image generally. 5.Desire to reduce unpredictable risks deriving from the cost of environmental damage, particularly in view of the legislative change. 6.Desire for cost reductions through savings in material and energy use and waste disposal costs. All industrial activity has an effect on natural resources, water supplies and on the land. Where the continual supply of resource material has been the concern of the 1970s, since the mid 1980s there has been a shift. The most significant aspect is the awareness that the globe has a finite capacity to absorb industrial waste and pollutants. This realization has led to the development of what is known as sustainable development –development that meets the needs of the present without compromising on the ability of the future generations to meet theirs. (World Conference on Environment and Development, 1987:89) Sir Geoffery Chandler chairman of Amnesty International’s UK Business Group writing on behalf of a wide range of interest groups in a letter published in the Financial Times put the matter this way’ “Society needs to know what companies are doing to uphold human rights, protect the environment and help to tackle poverty, in exchange offer the legal privilege of limited liability; companies should disclose comprehensive information on their social and environmental performance alongside their financial results. At the turn of 20th century the following list of practices are commonly viewed as ethical within a business context. Employing good environmental practices Contributing to good causes Participating in community activities Paying employees a fair wage Providing safe and clean working conditions Not fixing the Books Being loyal to the customers Keeping your word in the deal Not fixing the prices with the competitors Not building in product obsolesce Negotiating morally with customers Equal employment opportunities Information disclosure could be viewed voluntary in response to market and /or non-market pressures. It could also be a mandatory requirement as a part of regulatory measures seek to ensure that the adequate and standard information is available to stakeholders/ consumers. Since the primary commercial motive would seem to be, profit (rather than overriding moral laws) tension is created at the interface between profit and other questions of moral value. Ethical sound practices introduced throughout an organization in the context of workers participation and commitment, are the hallmark of a progressive management aspiring to long-term survival. Institutional Mechanisms – the emergence of command and control approach The earliest of the approaches for managing or rather controlling the impact of human activities be it due to industrialized activities or due to any other significant impact primarily due to human interface, was through what is known as command and control mechanisms. One of the underlying beliefs in this type of approach is that the natural environment has its own self-regenerating capacity if it is not adversely affected by the human induced developmental activities. Command and control mechanisms involve one single set of institutions mostly the government bodies with power vested on them as statutory bodies trying to regulate all the human activities with different levels of impacts. The legal instruments were thought to be the most effective tools for controlling the human activities so that there are checks to the levels to which the natural resources can be exploited. So in the absence of well established standards in this approach each country developed its own legal enactments. Every country identified its own major environmental issues and media to be addressed to and developed their rules and regulations and made the rules and regulations as comprehensive as possible. In the command and control model the initiative is more from the regulatory body based on the resources available at its disposal and the overall level of tolerance to environmental deterioration and the expectations from the people for the quality of life that the desire to live, the tolerance level and the extent to which environmental problems are felt to be serious social problems. The countries have indeed come up with comprehensive legislations to counter environmental problems and made provisions in their budgets to amicable solve these problems. However there are a lot of variations in degrees of enforcements. The effectiveness of enforcement of regulations also leaves much to be desired. Very often, there is also conflict of interest between the government and the major industrial bodies as the industry does contribute to the economy so the industrial support becomes very vital to the whole issue of environmental impact mitigation. Though the rules and regulations are in place, very often it is not until a major environmental industrial disaster that one comes across effective environmental monitoring taking place. So there are wide different levels of enforcement of environmental regulations. This often poses the problems in inter- country trade relations and multi national operations to name only a few. It is also difficult to pinpoint as to which issue among the myriad environmental issues like air pollution, water pollution, Hazardous waste management, global warming, Green House Effect, Climate Change, Displacement of people due to developmental activities and many others, is of common interest to the countries falling in line to cooperate for trade and other mutually benefiting activities. Historically environmental trigger events have varied largely among countries. For example, when the industrialized countries provide to priority to climate change and quality of life, less developed countries have their handful of waste management problems and day-to-day environmental pollution related problems due to poor enforcement mechanisms. The question of providing relative importance to environmental problems looms large in the government agendas from time to time. Therefore, the search for alternative mechanisms to address the environmental problems is very significant. It is significant due to the following reasons. 1. The stakeholders involved in environmental decision-making process are many and environmental decision-making is critical to these stakeholders. The stakeholders would include the regulatory bodies, the industrial enterprises, the customers, the voluntary organizations, the suppliers, the community and significant others. The regulatory approach does not provide an opportunity for the other stakeholders to be meaningfully involved. It is a one-way approach of conforming to rules. 2. The regulation driven change is less tangible. It takes a lot of time to generate reports, use the department of justice to bring about longstanding judgment to create impact on other defaulting units. The process of change is very slow and involves a lot of legal documentation. 3. The free riders –people (in all sectors industrial unit owners, people who refuse to segregate the waste etc) who feel that they can continue with the existing misbehavior as far as their environmental practice is concerned remain, as a constant conviction for others not to change. 4. There are different levels of enforcement and the punishment for non-conforming is very low so people do not perceive his as a threat. Therefore, the system, which believed in creating conformation by using punishment for defaulting, is under question. The market driven strategies as a group refers to strategies that evolve from the market i.e. people who are using the resources as products controlling the moment of goods and services insisting on quality based environmental standards. Let us look at these strategies in some detail. What do you actually need to shift to a more effective market driven mechanisms? Here the word market is used as a larger term referring to all users of services rather than only the consumer oriented market. It also refers to different types of emerging markets for the cleaner technology markets that are emerging due to the increasing demands. One assumption that very strongly controls all types of market driven strategies is the increased level of awareness and appreciation for the environmentally friendly products and services and a deeper understanding of sustainability concept and its practical implications. The natural environment is the source of the materials and space on which all-human activities and all economies are built. At the same time, the natural environment has a finite capacity to supply these materials and to absorb the residues and waste materials produced by societies. These limitations appear at many levels, from arguments between next-door neighbors about noisy garden power tools, to global discussions over global warming or ozone depletion. The attempts of societies to address or solve these different problems vary, in terms of the methods and instruments employed, and with time, different approaches being favored in different periods. In historical terms, the dangers of overexploitation of natural resources have been known since ancient times, and some communities have been able to devise effective resource management systems, for example in local fisheries (Ostrom, 1990). Despite examples of successful resource management, global economic growth has taken place without a parallel development of environmental resource management systems. This, combined with the various sources of uncertainty and delays in observing and accepting environmental degradation, has produced a situation where growth and environment no longer seem to go hand in hand. The contemporary debate tends to reflect this and also the tendency environmental impacts have to show up at inconvenient points in time, for example when a recession limits the desire to impose further cost burdens on industry. While there are many environmental problems to deal with, society has only a limited number of ways to address them. Traditional regulation involving command and control measures has flourished since the 1960s, and continues to do so, despite the criticism of their distorting effects leveled at these approaches in most textbooks on environmental economics and policy (Baumol and Oates, 1988). Alternative suggestions have appeared, for example proposals that governments charge users of environmental resources by levying taxes to correct externalities (Pigou, 1920) or by giving subsidies for reduction of pollution. Alternatively, the right to pollute might be institutionalized and made a tradable commodity, the supply of which government can control (Dales, 1968; Tietenberg, 1985). Creation of deposit–refund systems also belongs to this category of economic instruments of environmental policy, being a combination of a tax and a subsidy. In recent years a number of alternative trends have appeared, which mainly seek to involve companies more directly. One trend is commonly referred to as environmental agreements (EEA, 1997) between governments and industries about specific environmental actions, typically in relation to waste management. Agreements between regulators and industries are voluntary, albeit negotiated under the implicit threat of severe regulations should the parties fail to reach an understanding. Another trend also involves voluntary action by companies and can be summarized under the heading ‘corporate environmental management’. It consists of a variety of elements: initial environmental review of a firm’s activities, creation of an environmental policy, environmental accounting, and reporting and corporate environmental strategies (Welford, 1996). These alternative trends also encompass such elements as the process of ‘greening’ the supply chain (Haas, 1996) and discussions of material flow management and environmental value chain management (Linnanen and Halme, 1996). Companies do not engage in these voluntary activities without reason. Agreements between the state and individual industries are, as noted, likely to be reached under the impression of a more or less well defined threat of less appealing alternative forms of regulation (costly command and control regulation, green taxes or tradable emissions permits). Similarly, the various elements of corporate environmental management systems may be adopted in order to pre-empt regulation, to satisfy existing or perceived demands from stakeholders in the firm or to generate competitive advantage. Some argue that the regulatory pressure will cause many problems and costs for industry ( Walley and Whitehead, 1994) while others argue that strict regulation can be a vehicle for the creation of competitive advantage because it forces firms to innovate (Porter and van der Linde, 1995). Firms face a wide and constantly changing range of environmental problems and challenges. Whereas initial effort in improving environmental performance was arguably driven by the ‘sins of the past’ (Love Canal, Bhopal to mind), firms are today facing a much wider range of issues. In addition to problems associated with past operations and current emissions firms now have to consider recycling, product life cycles and through these the total impacts (i.e. physical as well as social) of their products or activities over the life of the product. Put differently, firms face not only the deterministic elements of public environmental regulation, but also the additional demands from stakeholders and society. The constraints imposed on firms by regulatory authorities, are generally unequivocal, the other demands are not stated in terms of clear (more or less) regulatory requirements but remain more or less poorly defined, and open to interpretation. Thus, firms are required to capture signals from stakeholders and formulate environmental strategies based on interpretation of these signals. However, stakeholder approaches make the implicit assumption that managers are not the only locus of corporate control (Donaldson and Preston, 1995). While adoption of such approaches by firms may thus signify recognition of this, an alternative use of the stakeholder approach is as a tool for strategic surveillance, which allows better decision-making. The regulatory and stakeholder views of firms’ environmental performance can also be classified as ecopush and eco-pull, respectively (Meffert and Kirchgeorg, 1993), albeit with the caveat that the ecopush is ultimately a form of pull that acts through political economy mechanisms. Whether pressure to improve firm environmental performance comes from clearly defined regulators or other stakeholders is not the real concern here. What is interesting is the nature of the pressure in terms of the demands for some specific action on the part of the firm. While clearly defined regulations can be expected, the determination of what other stakeholders wish from the firm is subject to greater uncertainties as the firm receives, records and interprets signals from a variety of stakeholders. In the final analysis, such demands may range from broad admonitions to be more sustainable to very specific demands for the establishment of recycling systems or the use of ‘design for- environment’ practices. As a result of increasing pressure from various stakeholders to be in compliance with both government regulation and other more or less voluntary agreements and arrangements, a range of tools and approaches for corporate environmental management has evolved, including audits, reports, management systems and certificates. They are all more or less interrelated and setting up a classification can be done to suit any purpose. The key feature of these tools is that they have an internal orientation, in the sense that they serve mainly as instruments for evaluating the environmental performance of the firm. The inward-looking emphasis is driven both by regulators, who want a focal point to which responsibility for environmental effects can be assigned, and by other stakeholders, who concentrate on individual firms because they have a stake in those firms (defined as a function of the size of the specific investment associated with the stake (Hill and Jones, 1992). However, environmental impacts sometimes defy firm boundaries, either because products are inappropriately used or because impacts only occur under certain adverse conditions. This may render environmental management efforts concentrated on internal performance less effective, and at the same time require more emphasis on inter-organizational efforts. In many respects, an internal focus is encouraged by regulation and institutional conditions in the firm’s surroundings. These tend to be discussed in terms of compliance with regulation, exposure to liability and alignment with institutional norms, with only two reference points, the state of the law (‘are we in compliance?’) and the actions of the firm (‘can noncompliance be proven?’). Such a frame of reference naturally leads to an emphasis on internal performance. However, neither identification nor recognition of external stakeholders, nor providing information for them, in the form of environmental reports and other communication efforts, will necessarily result in broadening the firm’s environmental effort to include other parts of the supply chain in which the firm finds it. What we are looking for is mechanisms and practices that change the model of firm environmental effort from one with an internal focus (or a passive one) into a model that includes active engagement in inter organizational environmental management. However, before we can pursue such mechanisms it is necessary to define more precisely what the expression ‘inter-organizational environmental management’ means. The key difference between this term and the ‘intra organizational environmental management’ described in the models above is that the former term refers to firms that pursue all of the environmental implications of their actions, both in thought and in action. In other words inter-organizational environmental management involves learning about environmental impacts throughout the supply chain and the life cycle of products, and interacting with other firms or organizations in the supply chain to reduce these impacts. Following Sharfman and colleagues (1998) we can define inter-organizational environmental management as activities between a firm and either a supplier or customer, where the firms jointly engage in any process that alters, considers, monitors, evaluates, assists, directs, impacts, affects etc. any activity either within a firm, its business units or between firms that has a meaningful environmental consequence (Sharfman et al., 1998). Inter organizational environmental management practices include recycling systems, total quality environmental management, life cycle assessment, life cycle oriented environmental management and industrial ecology. Recycling is a long established but loosely defined term, which may involve efforts at several levels, depending on the exact nature of the process. To illustrate this point four levels of recycling have been proposed (Graedel and Allenby, 1995). At the highest and most desirable levels we find product maintenance, followed, in descending order of desirability, by recycling of subassemblies, components and materials, reflecting Graedel and Allenby’s preference for processes that minimize energy requirements. Acceptance of the ‘systems’ view of organizations acknowledges that they need to interact with their environment. Specific interest groups (stakeholders) exist in that environment and have an impact on (a stake in) the behavior and effectiveness of that organization. While these groups can be identified and classified in various ways, they have in common a willingness and competency to act with the intent to influence the organization. In turn, the organization is aware of these groups and recognizes the need to deal with them. To do so, the organization develops strategies that guide their behavior with regard to those groups and their interests. This behavior and supporting strategies are in turn based on the assumption that the groups (stakeholders) can be ‘managed’ to enable the organization to achieve its goals. 188 Organizational relationships with stakeholders can be viewed as a process composed of a number of identifiable components. Freeman (1984) recognizes three levels that can be used to analyse this process. The first is the ‘rational’ that addresses the issue of who are the stakeholders and what are their perceived stakes. The second is the ‘transactional’, where the focus is on the dealings between the organization and the stakeholders. Finally, there is the ‘processional’, which concerns the organizational processes used implicitly or explicitly to manage the relationships. Market driven strategies also presuppose the increased level of participation from the different groups of stakeholders. For example, a sustainable industry would integrate all its activities in a manner that best supports the environmental cause. It means that the company believes in environmental best practices and looks at the environmental performance in its category as a competitive advantage. Therefore, it creates a niche market for its environmentally friendly product by its way of doing business. Businesses, response to environmental issues is coming of age all over the world. Stakeholders exert pressures on businesses to demonstrate environmental responsibility. However, it is the source and extent of such pressures that determine business response. At present, it would appear that the principal pressure on UK businesses to demonstrate environmental responsibility is that exerted by government through legislation and regulations. Businesses must comply with such legislation or risk punitive action. Compliance is the basis of environmental responsibility. However, businesses may elect to go beyond compliance, which implies that they are implementing a leadership strategy, balancing risk against competitive advantage. An environmental leadership strategy can provide competitive advantage for a company in two ways: firstly, by catering for a demand in the market place for environmentally responsible products or services ahead of its rivals; secondly, by generating cost savings from practices that conserve energy and materials and reduce waste. Companies that have determined that their strategy should be one of environmental leadership will want to publicize this to their stakeholders. The underlying pressure to improve environmental responsibility is the legislation introduced by governments, although this in turn is determined by a variety of economic, social, and scientific pressures. Environmental legislation in the UK is increasingly being driven by the European Union and its rate of introduction shows no sign of declining. As the requirement to implement legislation falls equally on all businesses, no business can claim that it is singularly disadvantaged. Compliance may increase costs but, if this is so, then all companies, in principle, are subject to the same cost increases. Such costs would be passed to the customer and properly so, since it is the wants of the customer that cause environmental harm. The only inequality that can arise is that some companies manage the cost of compliance more efficiently and effectively than their competitors and gain advantage by producing product at a lower cost. However, companies that manage costs, from whatever source, more efficiently and effectively than their competitors gain advantage. Given that a business must generate profits to survive, environmental leadership (although it demonstrates social responsibility) is unlikely to be just altruism. It has to be a strategy to improve competitive advantage. If that is so, then identifying and quantifying the business benefits becomes essential if the strategy is to be justified. Strategy is sometimes perceived by small companies to be the province of large companies. However, if the estimate that over 70% of businesses worldwide are small- or medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (O’Laoire and Welford, 1995), or that in the UK 98 percentage of all businesses is classified as small (Patton and Baron, 1995), how relevant is an environmental leadership strategy to such businesses? If caring for the environment can be demonstrated to reduce business costs, then even the smallest business may have an incentive to go beyond compliance. Companies and managers that take the environment seriously change not only their processes and products but also their organization (Welford, 1992). For many forward-looking organizations, environmental responsibility has become an aspect of the search for total quality and, as such, zero defects mean zero negative impact on the environment. Close parallels may be drawn between aiming for total quality and the concept of environmental management. For example, just as remedying errors and defects is more expensive once the product has left the factory, so is cleaning up after an environmental accident, rather than preventing damage in the first place. For a company with a TQM system in place the introduction of an integrated and effective environmental management system (EMS) should not be difficult. The main elements of a TQM system that need to be reflected in any EMS are teamwork, commitment, communications, organization, control and monitoring, planning and an inventory control system. 1. A sustainable consumer would definitely read the fine prints and look for products that are from companies with sound environmental practices. In the long run, the customer will demand a higher level of environmental quality products from the companies. 2. The market or the external environment to the enterprise creates a competitive environment to the companies by choosing to sell product and services only from companies following environmental quality practices. In other words, there is no market for products, which are hazardous/environmentally unfriendly products in the market place. 3. The countries cooperating at the international level to eliminate unsustainable practices and entering into dialogue to bring about better environmental consciousness. 4. Keeping in mind the eight principle of Rio conference Agenda 21. “To achieve sustainable development and a higher quality of life for all people, States should reduce and eliminate unsustainable patterns of production and consumption and promote appropriate demographic policies”, an increased level of environmental awareness created by the integrated efforts of different stakeholders. E.g., The government seeking collaboration with industrial associations to foster environmental best practices in the unorganized sector small-scale industrial units. 5. Initiate an effort to visioning of environmental best practices at all levels. Market driven strategies reflect the proactive approach. It is certainly due to the early maturity process of adapting to command and control mechanisms, which is a reactive approach of reacting to worse reported form of behavior. The government can also initiate market strategies or the regulatory bodies based on their own experience derived from regulating the different sectors through the compliance mechanism. The other stakeholders can also participate in the process and bring about change at a shorter term. Voluntary organizations can participate largely. The consumer can demand for better environmental quality and pose a threat to the very existence of the firm. Therefore, the environmental movement itself will become a customer driven force. 1.Total quality environmental management Total Quality Environmental Management is a practice or philosophy of focusing on customer needs and expectations, and is derived from total quality management (Piasecki et al., 1998). It is closely linked to an organization’s environmental management system but with the added dimensions of organizational commitment and customer satisfaction (Piasecki et al., 1998). The potential for inter-organizational environmental management is present in the sense that customers are included. However, TQEM as a system or approach does not go into the nature of customer satisfaction (which may not be related to environment at all) nor does it envisage interaction about other matters than satisfaction. 2Life cycle assessment The practice of life cycle assessment has been divided into four components, which together help describe what is a vaguely defined term. The SETAC ‘code of practice’ identifies scoping, compilation of quantitative data on direct and indirect materials: energy inputs and waste emissions, impact assessment (classification of effects, characterization and valuation) and improvement assessment (analysis of implications for the purposes of prioritization and assessment of policy alternatives) (Ayres, 1995). The recently published ISO 14040 series of standards on LCA defines the practice as ‘a technique for assessing environmental aspects and potential impacts associated with a product by compiling an inventory of inputs and outputs of a system, evaluating the potential environmental impacts associated with those inputs and outputs, and interpreting the results of the inventory and impact phases in relation to the objectives of the study’ (ISO, 1998). Strong reservations have been expressed about the many inherent weaknesses in the practice of the LCA approach. Because the costs of producing LCAs increase with the distance to the source of information (both in spatial and in transactional terms) companies conducting an LCA are likely to shift rapidly from using primary data to using databases . 3.Life cycle oriented environmental management Despite the insistence that LCAs themselves do not involve action, LCAs clearly invite such action on the part of the focal organization. However, while LCAs are becoming increasingly well defined, very little is known about how firms react to the findings of LCAs (Sharfman et al., 1998). Nevertheless, there are some indications to go by. First, the concept of LCOEM has been defined as consisting of three necessary elements inherent in it. First, LCOEM includes an understanding that organizations have effects on the natural environment through all elements of their total physical system from the creation of inputs to the final disposal, decontamination or recycling: reuse of outputs. Second, inherent in LCOEM is a coincident reduction in resource utilization both through production that is more efficient and design as well as waste management. Third, LCOEM can only be achieved through coordinated efforts of all parts of the organization, its suppliers, and its customers (Sharfman et al., 1998). Given this definition, there is no doubt that LCOEM can be included in the ‘inter organizational environmental management’ category. Furthermore, LCOEM is clearly an umbrella term and practices such as product stewardship, supply chain management, and design for environment are all variations on a similar theme that involves inter organizational effort. 4.Industrial ecology The final inter-organizational practice considered here is industrial ecology or industrial ecosystems. This is a term where definitions are problematic and need to be resolved before we can continue. One of the leading texts on industrial ecology defines the concept as ‘the design of industrial processes and products from the dual perspectives of product competitiveness and environmental interaction’ (Graedel and Allenby, 1995). Ecology and ecosystem are terms borrowed from biology although there are many systemic similarities between industrial and natural ecosystems. Most important, in terms of approaching the idea users of the term seem to have in mind, is that ‘The system has evolved so that the characteristic of communities of living organisms seems to be that nothing that contains available energy or useful material will be lost’ (Frosch, 1992). In this understanding, the term signifies the systemic effort to minimize or eliminate waste in all its forms. The crucial question that can be asked after reading most discussions of industrial ecology is ‘how will it be organized?’ Patricia Dillon comes close when saying that she feels that ‘cultural and organizational changes within industry (as well as changing the behavior of consumers and government agencies) will most likely present greater obstacles [than technology]’ (Dillon, 1994). One possible answer to the organizational problem is large integrated firms designed to capture as many ‘returns to system integration’ as possible (Ayres and Ayres, 1996). However, emphasizing that this is not a feasible design option, Robert Ayres instead concentrates on the need for a major ‘export product’ around which the system could be based. In terms of organization, Ayres presents models for the cooperation that industrial ecosystems require, large-scale vertical integration, the keiretsu family of firms model with interlocking shareholdings and finally the top-down marketing firm type of co-operation (Ayres and Ayres, 1996). Despite these uncertainties, industrial ecology is, because of its systemic emphasis, clearly an inter-organizational approach. As environmental ambition increases, so does the complexity of the management task required to fulfill these ambitions, regardless of whether they are driven by market forces The institutional process favors the internally oriented environmental management practices because they allow firms or organizations using them to show reliability of performance and high levels of accountability. Peripheral features are less subject to inertia while core features (organizational goals, forms of authority, core technology and marketing strategy) are more so. This distinction is also reflected in the intra organizational and inter-organizational approaches to environmental management. The former group of tools represents features that can be added on to an existing organization without significantly affecting its fundamental structure. The inter-organizational approaches, in contrast, envisage increasingly substantial changes in the way an organization works. This includes asking fundamental questions about the moral and social justifications on which the organization is built, for example questioning whether a toxic chemical can be produced in a sustainable manner, used and disposed of. The shift from regulatory mechanisms to market driven strategies will provide better participation from different interested parties. Several of the emerging strategies like Total quality environmental management, Life cycle assessment, ISO 14000 Environment Management System, and sustainable development, as the underlying principle in all aspects of business and social interactions is the emerging trend. The emphasis on control alone will not be sufficient to bring about the required level of change in environmental behavior. REFERENCES Central Pollution Control Board. 1997. ECOMARK: a Scheme on Labeling of Environment Friendly Products. Delhi. Environmental Committee. 1991. Eco-Labeling–Eighth Report of The House of Commons Environmental Committee. London: HMSO. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1998. Environmental Labeling: Issues, Policies, and Practices Worldwide. Pollution Prevention Division: Washington, DC. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 1998.Environmental Labeling: Issues, Policies, and Practices Worldwide. Pollution Prevention Division: Washington, DC. Freeman RE, Reed DL. 1983. Stockholders and stakeholders: a new perspective on corporate governance. California Management Review 25(Spring). Porter M, van der Linde C. 1995. Green and competitive. Harvard Business Review 75(3): 120–134. Hemmelskamp J, Brockmann KL. 1997. Environmental labels: the German ‘Blue Angel’. Futures 29(1): 67–76. ISO World. 2002. The Number of ISO14 001/EMAS Certification/Registration in the World. http://www.ecology.or.jp/isoworld/english/analy14k.htm [21 August 2001]. Nagel L. 1991. Giving Guidance to the Green Consumer- Progress on an Eco-Labeling Scheme for the UK, Report by the National Advisory Group on Eco-Labeling. Department of the Environment: London. Nicolson JA. 1994. In Introducing BS 7750: the Environmental Challenge, Werksman J, Roderick P (eds). Earthscan: London. Shrivastava P, Hart S. 1994. Greening organizations.International Journal of Public Administration 17(3/4): 607–635. Dr Knud Sinding, Department of Organization and Management, Aarhus School of Business, Haslegaardivey 10, DK 8210 Aarhus, Denmark. UNCTAD Secretariat. 1994a. Eco-Labeling and Market Opportunities for Environmentally Friendly Products. International Cooperation on Eco-Labeling and Eco- Certification Programmes and Market Opportunities for Environmentally Friendly Products. Welford R. 1997. Corporate Environmental Management :Culture and Organizations. Earthscan: London. Welford R, Gouldson A. 1993. Environmental Management and Business Strategy. Pitman: London. Welford R. 1995. Environmental Strategy and Sustainable Development. Routledge: London. 1 Risk Communication: A case study of Mumbai deluge on 26 July, 2005 Dr.Neeta Inamdar*, Dr.Bala Krishnamoorthy* Case lead: It’s mid July. The city of Mumbai looks beset with dark clouds. Heavy rains aren’t new to Mumbai but the deluge of 26 July 2005 has put an end to the idea of romantic rains for Mumbaikars ( People of Mumbai). It seems it is already pouring in some parts! Anxious Mumbaikars start tuning into their radios; try to get connected with family and friends for more information; Are the local trains running? Is there a traffic jam? Is it going to rain heavy? How do I reach home? A message is flashed on mobiles - on some not all - heavy to very heavy rains expected in next 48 hours and sender to your surprise was the BMC (Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation). Now, does it answer all those questions of Mumbaikars? Is this communication sufficient? What else needs to be done? The SMS was sent but it didn’t rain as heavily as expected. Next day, The BMC commissioner is pondered over this. It was not BMC’s mistake if it didn’t rain as expected. Will people believe such a message in a similar situation at a later date, again? After a week, a similar situation yet again, a similar warning from the Met department - heavy to very heavy rains….The BMC commissioner is in a fix, whether to communicate it to the public or not. Met department’s forecast has already failed twice but does not mean it is going to be so again. He just deliberated over the situation that Mumbai witnessed during the deluge on 26 July as he thought it was apt before taking a decision on communicating risk to the people. 1 Dr.Bala Krishnamoorthy, Professor & HOD Business Policy, NMIMS Dr.Neeta Inamdar, Asst.Professor, Business Policy, NMIMS Mumbai deluge: Rain rain go away Come again but not this way….! This is a kindergarten rhyme rewritten by mumbaikars who struggled through those troubled waters on July 26, 2005.The infamous deluge claimed more than a thousand lives. Low lying areas along the Mithi river like Dharavi, Kurla east and Mahim and Santa Cruz and Kurla west near Mumbai International Airport and Sion on the Mahul river were inundated. Many people in Mumbai also did not till then know that Mithi was a river for real, an official carrier of waste and garbage otherwise. It overflowed, railway tracks disappeared, and buses got stranded half immersed in dirty water. Water logging was such in some low lying areas that it gushed into the houses on the ground floors. Slum dwellers hutments were washed away. People out of the home struggled to contact their kith and kin in a state of shock. The rain played havoc like never before. . A city which is a witness to many rags to riches stories has a similar one for itself. It was once a group of seven islands, mostly deltaic mudflats in the 16th century. It passed through the hands of Portuguese and then England in the 17th century. Most of the reclamation works were undertaken in the mid 19 th century when the seven original islands were joined up. Undeterred by the problematic geomorphology and complex hydrology the city continues to grow vivaciously. However this growth has been unplanned, haphazard and heterogeneous. It houses 3-5 story apartments, industrial estates, shopping malls, sky scrapers, slums, flyovers, drains - wide and narrow some deep and some shallow. Mayanagari ( Dreamers paradise) Mumbai, the commercial capital of India, spread across 438 square kilometers has a population of 12 million people in the greater urban region with the escalating influx of people from across the country. It is city known for its uniqueness in more than one ways – be it the efficiency of dabbawallas and local transport facilities or the dreamy world of bollywood. It is also known for its darker sides of having the Asia’s largest slum and as a crime head quarter of the underworld. Greater Mumbai Metropolitan area or Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) area is divided in two revenue districts viz. Mumbai city District and Mumbai suburban District. Greater Mumbai of Maharashtra is entirely urban. It extends between 18o and 19.20o northern latitude and between 72o and 73.00o eastern longitude. It has an east to west extend of about 12 km. where it is broadest, and a northsouth extend of about 40 km. Geographically speaking, Greater Mumbai is an island outside the mainland of Konkan in Maharashtra separated from the mainland by the narrow Thane Creek and a somewhat wider Harbour Bay. At present, it covers the original island group of Mumbai, and most of the island of Salsette, with the former Trombay island appended to it in its Southeast. A small part in the north, the Salsette island however, lies in Thane District. The Salsette-Mumbai island creek and the Thane creek together separate it from the mainland. Thus the area of Greater Mumbai is surrounded on three sides by the seas: by the Arabian Sea to the west and the south, the Harbour Bay and the Thane Creek in the east - but in the north, the district of Thane stretches along its boundary across the northern parts of Salsette. The BMC limit extends up to Mulund, Mankhurd and Dahisar Its height is hardly 10 to 15 meters above sea level. At some places the height is just above the sea level. Part of Mumbai City district is a reclaimed land on Arabian sea coast. Mumbai City is one of the first four metropolitan areas in India. During last 35 years there has been a continuing shift of population from Mumbai city District to Mumbai Suburban District and now further to part of Thane District A commission that was constituted after the 2005 floods headed by former irrigation official Madhavrao Chitale took cognizance of the earlier studies that identified 235 flooding points within the city as well as 10 sections of the Central Railway and 12 along the Western Railway, prone to flooding. Chitale commission reported that the rapid, uncoordinated growth and poorly regulated construction of high value have added to the problems. Solid waste management has gone unaddressed which creates blockages of drains lead to flooding. Hundreds of commercial and small industries some of them dealing with scrap metal and waste oil were found to be illegally located along the Mithi River in the zone between Mumbai’s Vihar Lake and Mahim Bay. Unfortunately Mumbai has 53 per cent of its population living in slums divided among more than 2000 different slums settlements. To add to the woes is the drainage system which outfalls into the Arabian sea. There are no gates to shut them against storm surges and high tide. 70 of the 300 outfalls are presently below sea level due to subsidence. There was another argument that elevation of land along the Mithi river by the Airports Authority of India that blocked off part of the Mithi’s flood plain contributed to the 2005 floods. The floods could not be avoided in spite of efforts by control rooms that exist in greater Mumbai. Communication plays a vital role in catastrophe management. The communication and public information system in Mumbai is presented in a box below. Presently the following Control Rooms exist in the Greater Mumbai Police Control Room BMC Control Room Fire Brigade Control Room BEST Control Room Central Railway Control Room Western Railway Control Room Konkan Railway Control Room District Control Room for Mumbai district District Control Room for Mumbai Suburban district Civil Defence Control Room BOX1 Communication and Public Information Systems in Mumbai Public Information System (PIS) demands that people are kept aware and informed in the entire cycle of disaster management from the stage of risk assessment. A lot of community education, awareness building, plan dissemination and preparedness exercises has to precede if a meaningful PIS is made operational. Thus, these tasks have already been listed in the DMP. Involvement of citizen’s groups, NGOs in plan dissemination and preparedness is going to be one of the crucial elements. Additionally, familiarity with warning systems and regular drills to respond to such a system and specific do’s and don’ts for the community during the disaster situation have also been suggested. Respective agencies have been assigned to undertake such tasks Wireless Communication For efficient co-ordination and effective response, communication amongst line departments such as BMC, police, fire brigade, municipal/government hospitals, meteorological centre and BEST is essential. This can be ensured by upgrading the present communication system with a more efficient wireless system. The wireless system should be full-duplex and also enable communication with different line departments. Display Boards Also, as a part of mitigation measure, electronic information display boards should be installed which could be monitored from BMC control room. The messages displayed are essentially instructional during the time of disasters. The information displayed will direct public response and help the administration in localising the impact. In the normal times, the same display boards can be used for community education on social issues and disaster preparedness messages. The Traffic Police and BMC have jointly identified 44 locations where these display boards can be put-up. The critical locations are all rail terminus, airports, MSRTC depots, BEST bus stations, Air-India Building, Regal Cinema, Girgaum Chowpatty, Haji Ali, Worli naka, Gadge Maharaj chowk, Dadar T.T, Sion, Bandra, Mankhurd, Vashi, Panvel, Ghatkopar, Mulund, Thane, Dahisar, Virar etc. Public Adress Systems in local trains In order to keep the passengers informed about the movement of rail services, especially during monsoon and other contingencies, public address systems needs to be installed in all the rakes. This would also require a wireless contact between the guard and the railway stations. Such a system would allow the passengers to take timely decisions with respect to their travel Public Address Systems at railway stations and bus stations All railway stations, BEST bus stations, MSRTC bus stations within MMR region, should have the facility of public address systems to keep the passengers updated on traffic situation. Cable TV networks Information put on the cable TV networks may help the citizens to take decisions with respect to their travel. Since cable TV operators have local coverage, a ward wise arrangement will have to be made for information inputs. GIS All the infrastructural facilities and utilities in Greater Mumbai need to be mapped on to a GIS application on a multi-user basis. There is therefore a need to develop a GIS on a scale of 1:1000. This would help the planners, administrators, emergency services and utility providers. Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai Disaster Management Plan http://www.mdmu.maharashtra.gov.in/pages/Mumbai/mumbaiplanShow.php Many Mumbaikars however, are not aware of these arrangements made for damage control. They discuss the severity of problems; some of them are well informed whereas, the rest cling to rumors and some to less authentic sources. This sharing and spreading of unauthentic information leads to chaos and panic at the time of emergency. This also calls for immediate attention to risk communication. The major difference between the normal communication and risk communication is that the risk of misinterpretation of any message is too high during emergency situations. The two factors on which the effectiveness of risk communication depends is the authenticity of the source and simplicity and clarity with which message is put across to the people. The differences between normal communication and risk communication are presented below. Differences between normal and risk communication Normal communication Risk communication Takes place in a comfort zone Takes place in a sensitive zone Risk of misinterpretation is low Risk of misinterpretation is high A normal clear communication suffices A cautious communication is a must The response to communication is usually The response is usually faster and forceful simple and direct This communication follows normal course This stirs emotions and leads to chain of flow reaction Authenticity of source is not questioned Authenticity of source is of utmost often importance Channels of communication are chosen Channels of communication have to be liberally chosen very cautiously Credibility of channels of communication Credibility of channels of communication are not assessed seriously before selecting need to be assessed seriously before selecting Need not be very formal It has to be very formal Can be a spontaneous communication It has to be systematic, planned and deliberate communication May or may not be factual It has to be factual There is a need for a thorough understanding of the concept of risk communication before resorting to risk communication. Even within risk communication there is a need to have different approaches for communicating risk before disaster, during disaster and after disaster as the responses to a similar message can differ in these three phases. The simplistic model of communication of sender – medium – receiver can also help to make right decisions at the time of communicating risk. The importance of precision in communication has to be understood as all are in their most active mode while communicating risk. Who communicates at the time of a catastrophe is crucial as the people believe information coming from the horse’s mouth. The extent to which they believe is determined by the authenticity of the source. In the above example, the BMC commissioner is expected to speak and guide people in the right direction during the time of emergencies as in case of July 26. The integrity of the information that is disseminated by such source will determine the credibility of the source over a period of time. Therefore, the commissioner is confused whether to communicate the risk and if yes, how. Though it is true weather predictions of Met department are questioned and contested quite often, he is bound by duty to communicate it to people, though its repeated failure may affect the credibility of the source and hence the information disseminated by such source. The commissioner has to communicate especially in light of people’s right to information. According to the information handbook under Right to Information Act 2005, the Right to Information Act intends to set out the practical regime of Right to Information for citizens to enable them to access the information under the control of public authority in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of such authenticity. Section 2 (h) of the Act defines “public authority” as any authority or body or institution of selfgovernance established or constituted by or under the constitution or by law made by the parliament or any state legislature or by notification issued by the appropriate government. It includes body owned, controlled or substantially financed by the government. In accordance with the provisions contained in section 2(j) of the Act, Right to Information means tight to information accessible under control of a public authority. Risk communication Risk communication is a part of larger process of risk analysis which includes 1. Risk assessment 2. Risk Management 3. Risk communication Risk is a perceived potential threat, a negative impact that an event or process can have on living as well as nonliving constituents of the environment. This definition is inclusive of all kinds of risks – environmental risks, financial risk and industrial risk and almost all those things that can have potential negative implications. In everyday usage, risk is often used synonymously with the probability of a loss. Risk could be said to be the way we collectively measure and share this “true fear” – a fusion of rational doubt, irrational fear and a set of unqualified biases from our own experiences. A recognition of and respect for the irrational influences on human decision making may go far in itself to reduce disasters due to naïve risk assessment that pretends to rationality but in fact merely fuse many shared biases together. Though there are no concrete ways of measuring risk attempts have been made. It is explained as a result of the probability of an event occurring with the impact that event would have and the losses that can be incurred for one such accident. Risk = Probability of an accident x losses per accident The problem that arises in the above model is that an extremely disturbing event that all participants wish not to happen again may be ignored in analysis despite the fact that is has occurred and has a nonzero probability. Sometimes an event that everyone agrees is inevitable may be ruled out of analysis due to greed or an unwillingness to admit that it is believed to be inevitable. These human tendencies to err and wishful thinking often affect even the most rigourous applications of the scientific method and are a major concern. However, decision making under uncertainty must consider cognitive bias, cultural bias and national bias. High-concern situations involving risk create substantial barriers to effective communication and evoke strong emotions such as fear, anxiety, distrust, anger, outrage, helplessness and frustration. When communication environment becomes emotionally charged, the rules for effective communication change. Familiar and traditional approaches often fall short or can make the situation worse. The National Academy of Sciences defines risk communication as, “an interactive process of exchange of information and opinion among individuals, groups, and institutions. It involves multiple messages about the nature of risk and other messages, not strictly about risk, that express concerns, opinions or reactions to risk messages or to legal and institutional arrangement for risk management. The scientific literature on risk communication addresses the problems raised in the exchange of information about the nature, magnitude, significance, control, and management of risks. It also addresses the strengths and weaknesses of various channels through which risk information is communicated: press releases, public meetings, hot lines, websites, small group discussions, information exchanges, public exhibits and availability sessions, public service announcements and other print and electronic materials. Evaluation studies have consistently demonstrated the effectiveness of risk communication practices in helping stakeholders achieve major communication objectives: providing the knowledge needed for informed decision-making about risks; building or rebuilding trust among stakeholders; and engaging stakeholders in dialogue aimed at resolving disputes and reaching consensus. The evaluation literature has also demonstrated the major barriers to successful risk communication including conflict and lack of coordination among stakeholders and inadequate risk communication planning, preparation, resources, skill, and practice. It is a two-way interactive process that respects different values and treats the public as a full partner. However many personnel from agencies and organizations involved in risk lack the knowledge, sensitivity and skills needed for effective risk communication. They adhere to the DAD Decide, announce and defend model and proceed with limited understanding of the various stakeholders’ values and concerns. Whether the objective is to motivate people to take action, calm people down when they are enraged, or to educate and inform, there are specific techniques and strategies to effectively communicate and educate regarding issues of safety. Approaches to communicating risks Communication Process Approach - Traditional model of communication National Research Council's Approach - interactive process of exchange of information and opinions among individuals, groups and institutions concerning a risk or a potential risk to human health or the environment. Mental Models Approach - this approach is grounded in cognitive psychology and artificial intelligence approach. Crisis Communication Approach - This approach holds that those who are communicating the risk should use every devise to move the audience to appropriate action. Convergence communication Approach- Communication is an interactive long -term process in which the values (cultures, experiences, background) of the risk communication organization and the audience affect the communication process. Three-challenge approach - Risk communication is viewed as having three challenges: Knowledge challenge, a process challenge, and communication skills challenge. Social constructions approach - This approach focuses on the flow of technical information and values, beliefs, emotions. Hazard plus outrage approach - risk should be viewed as hazard plus outrage. The variety of approaches available to communicate risk reinforces the fact that risk communication is extremely critical form of formal communication, and it demands more attention. It has to be done in a responsible manner. Principles of risk communication The risk communication literature discusses a number of principles regarding how best to communicate risk. 1.Know your communication limits and purpose -to effectively communicate risk, you must know why you are communicating and any limitations to your ability to communicate risk .The communication limits may be a) Regulatory requirement b) Organizational requirements c) People’s requirement 2.Whenever possible pretest the message -the message should be reviewed by a group of people to determine the suitability and to ensure that the risk message achieves the desired results. 3.Communicate early, often, and fully- this principle has two aspects: timing of communication and amount of information to be released. Risk communication may be timed to involve the people all along the process of communication. Conclusion Educators may be telling people that a perceived hazard is not as serious as they may think. Peter Sandman’s formula for effective risk communication can be of help while strategizing communication. (Risk is the outcome of Hazard and Outrage. An understanding of the nuances of risk communication helps better in dealing with catastrophe at various levels of - before, during and after disasters. A proactive thinking can reduced the damage if not avoid it all together. However, solutions to such problems lie in developing new models of public private partnership. In the above case a proactive thinking on the part of MBC could have averted the confusion that prevailed at that time. A new model of public private partnership in handling integrated disaster management communication is the need of the hour. Questions: 1. Discuss the significance of risk communication? 2. Do we need special expertise for risk communication? 3. What is the role of BMC in enhancing effective communication? 4. Discuss the role of citizens in bridging the gaps in communication. 5. Develop a model for improving public private partnerships in disaster management. Reference 1. Bavadam Lyla (2005) There was no advance warning, an internview with Krishna Vatsa, Secretary, Relief and Rehabilitation, Government of Maharashtra, Frontline, Vol.22. No. 17 2. Fisher Ann, Pavlova Marial, Covello Vincent, Evaluation and Effective Risk Communication Workshop Proceedings, available http://www.health.gov/environment/casestudies/csapp3.htm 3. Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai Disaster Management Plan, available http://mdmu.maharashtra.gov.in/pages/Mumbai/mumbaiplanShow.php 4. ICT for Disaster Risk Reduction The Indian Experience, Ministry of Home Affairs, National Disaster Management Division, Government of India 5. Jagdevan Shibu (2005), Mithi River: The Official Garbage Carrier of Mumbai, IndianNGOs.com, available http://www.indianngos.com/issues/water/resources/articles-mithiriver.htm 6. Krishnamoorthy, Bala (2006) Environmental Management, chapter 3, prentice hall of India, New Delhi 7. Olekno, W W. (1995), Guidelines for improving risk communication in environmental health, Journal of Environmental Health, 58 (1) 20-23 8. Risk Communication: Working with Individuals and Communities to Weigh the Odds, Prevention report, US Public Health Service, February/March 1995 available http://odphp.osophs.dhhs.gov/pubs/prevrpt/Archives/95fml.htm 9. Rowan K E (1991), Goals, obstacles and strategies in risk communication: A problem solving approach to improving communication about risk, Journal of Applied Communication Research, 19, 300-329. 10. Sandman Peter .M (1987), Risk Communication: Facing public outrage, EPA Journal, 13, 21-22 11. Sandman Peter M (1993), Responding to community Outrage: Strategies for effective risk communication, Fairfax, VA: American Industrial Hygiene Association 12. Schaefer Anja and Harvey Brian(2000), Environmental knowledge and the adoption of ready made environmental management solutions, Eco-Management and Auditing, 7, 74-81 13. Wisner Ben, Mosnoon, market and Miscalculations (2006): The political Ecology of Mumbai July 2005 Floods available http://www.radixonline.org/resources/wisner-mumbaifloods2005_22jan2006.doc