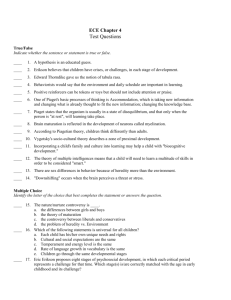

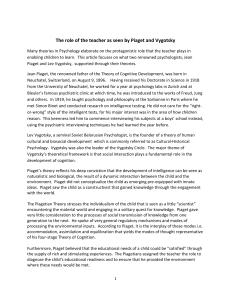

Jean Piaget - The Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition

advertisement