The paper presents the findings of a research project on the in

advertisement

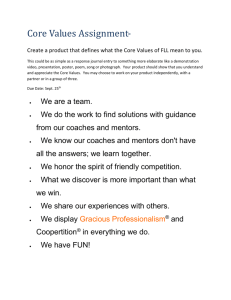

The in-classroom use of mobile technologies to support diagnostic and formative assessment and feedback Dr Ann Ooms – Dr Tim Linsey – Marion Webb – Andreas Panayiotidis Kingston University Abstract The paper presents the preliminary findings of an HEA Pathfinder research project investigating the use of in-classroom use of mobile technologies to support diagnostic and formative assessment. The mobile technologies used include electronic voting systems, i-Pods, mobile phones, Tablet PC’s and interactive tablets. Literature Review According to the National Student Survey (HEFCE, 2006), feedback on assessment is the weakest area for most universities in the UK. However, assessment is an important component of education. It “… is a broad term defined as a process for obtaining information that is used for making decisions about students, curricula and programs, and educational policy” (Nitko, 1996, p. 4). The definition of assessment given by Wiggins and McTighe is similar, yet more focused on the impact of the curriculum on student learning: assessment is … “the act of determining the extent to which the curricular goals are being and have been achieved.” (Wiggins & McTighe, 1998, p. 4). Within the classroom, assessment has two purposes: (a) to assess the quality of students’ work, and (b) to assess the success of learning and teaching practices and achievement of learning objectives. The assessment of students’ work is used to assign grades and provide feedback to the students on their learning status, in terms of misconceptions or naive conceptions and strengths. This feedback will support students in focusing their efforts on improvement of skills and knowledge. The assessment of pedagogical practices is used by teachers to make decisions about their teaching. It gives them information about needs to change teaching practices (i.e. revisit certain components, give students an opportunity to practice more, add or change instructional activities). It also identifies students’ misconceptions or naive conceptions. A third goal of assessment, more used for research purposes, and more likely to be beyond classroom assessment, is to determine how students perform in Page 1 of 9 July 1, 2008 comparison to other students in different settings. This third goal of assessment is mainly used by educational researchers, to evaluate certain theories or to explore new teaching methods or curriculum. A fourth goal is to provide a tool for accountability systems. For all the above reasons, assessment is an important component of learning and teaching, for teachers and students alike. As the use of technology in education expands, so does educators’ interest in using technology for assessments. Researchers have demonstrated that the use of Electronic Voting Systems (EVS) can positively impact students’ conceptual understanding (DiBattista et al, 2004), students’ problem-solving skills (Cue, 1998; Hake, 1998), classroom interaction and discussion (Draper & Brown, 2004; Masikunas, Panayiotidis, & Burke, 2007), student motivation (Boyle & Nicol, 2003), their enjoyment of lectures (Elliott, 2003; Masikunas, Panayiotidis, & Burke, 2007) and test results (Cue, 1998; Elliott, 2003; Hake, 1998). Elliott (2003) also confirmed that the personal response systems provide a mechanism for collecting information about students’ understanding. Project Rational Thirteen academic staff members from 7 faculties used mobile technologies such as Electronic Voting Systems, Tablet PC’s, Interactive tablets, i-pods and Mobile phones, in the classroom for formative assessment purposes and to provide rapid feedback to students on their knowledge and understanding. The use of technology can support the following in-classroom interaction and feedback patterns: (a) from staff to student, (b) from student to staff, and (c) from student to student. Rapid feedback enhances the ability of students to identify their areas of weakness and strengths, which will assist them in focusing their study efforts. It will also assist them with identifying misconceptions or naive conceptions, especially in reference to challenging concepts. Thus, rapid feedback has the potential to enhance student learning. Formative assessment will also inform academic staff about their students’ understandings of concepts and thus provide staff with information about the effectiveness of their teaching practices. Academic staff can use this information to adapt teaching practices if necessary (i.e. revisit certain components, give students an opportunity to practise more, add or change pedagogical activities). Teaching practices can be adapted immediately if time allows, or in future sessions. Academic Page 2 of 9 July 1, 2008 staff may reflect on their teaching practices and plan changes for the future. This project rational is also graphically presented in Figure 1. Figure 1: Project Rational Methodology The evaluation study was conducted to learn about the strengths and weaknesses of integrating these mobile technologies into learning and teaching practices. The impact of these approaches on students’ learning, teaching practices, and students’ and academic staff perceptions will be measured. A mixed-methods methodology was used to collect data from academic staff (questionnaires, interviews, reflective journals, classroom observations), students (questionnaires), and mentors (interviews, reflective journals). In addition, attendance records, assessment strategies, assessment tools and assessment records are compared with those from the previous year. Data was collected prior, throughout and at the end of the project. Tailored Design Method (Dillman, 2000) was used for the development and administration of the questionnaires. The research project addresses the following questions: - Under which conditions can each of the mobile technologies be efficiently and effectively used for diagnostic / formative assessment in classroom settings? - What is the impact of the in-classroom use of mobile technologies for diagnostic / formative assessment on students’ attitudes toward the module? Page 3 of 9 July 1, 2008 - What is the impact of the in-classroom use of mobile technologies for diagnostic / formative assessment on students’ conceptual understanding? - What is the impact of the in-classroom use of mobile technologies for diagnostic / formative assessment on students’ test results? - What is the impact of the R3 project on teaching practices? How likely is it that that impact, if there is any, will sustain? - What is the impact of the R3 project on assessment practices? How likely is it that that impact, if there is any, will sustain? - What is the impact of the R3 project on attitudes on in-classroom use of mobile technologies? How likely is it that that impact, if there is any, will sustain? - What indicators are there of institutional commitment to and subsequent uptake of in-classroom use of mobile technologies? Staff participants were recommended by their faculty learning and teaching coordinators and by their faculty blended learning leaders, though participation was voluntary. The staff participants were supported by two mentors who have experience in the use of classroom technologies. Each staff participant was asked to integrate mobile classroom technologies into at least one module per semester. Class sizes of the project modules ranges from 15 to 550. Academic staff’s overall teaching experiences ranges from 4 to 25 years. Participants and mentors attended 2 full-day workshops and 2 half-day workshops about assessment and writing assessment items, hands-on activities with the mobile technologies and sharing of good practice. In addition, they participated in mentor led CAMEL meetings, where experiences and lessons learned were discussed and shared. Preliminary findings Eleven of 13 staff participants (11/13) successfully implemented mobile technologies in their classroom and plan to keep using the technologies in the next academic year. Data from their reflective journals show that staff experienced the use of the technologies as positive. “I felt a greater sense of involvement from the students in being able to see group feedback in real time.” “The students responded positively, many more of them were able to give responses (although anonymously) and we've spoken questions and it was therefore Page 4 of 9 July 1, 2008 possible to discuss the range of answers then if only one or two students would respond.” “The questions stimulated a lot of discussion.” Staff was also asked to reflect on negative or challenging aspects of the use of technology in their sessions. Just like the students, they mention the time it takes away from their teaching “The lecturer before me does not vacate the room in time and it takes a bit to set up”. However some don’t necessarily consider that a negative aspect as it forces them to reconsider their teaching approach and to identify alternative methods for delivering material. “I removed some of the material that I would normally talk about which was really just informational and pushed that into either additional slides, bits of reading outside the class, or a pod cast.” This demonstrates that some staff participants have been adapting their learning and teaching approaches beyond the specific requirements of the project. In addition, there is an indication that the use of a staff mentor approach to introducing new approaches to learning and teaching has been successful. Mentors have been available to support staff prior and even during lectures. Their support has been very appreciated by the participants. “Certainly that kind of encouragement and the warmth was very helpful.” “He was actually great. He came about a week before and he helped install the software which was really great. He was also really good with the first day; he was there. Plus he came here to just go back over PP Vote to make sure I really understood how to use it, the day before classes started. And then I had this one problem, there was just nothing I could do, and so I talked to him about it and he got me a laptop.” Preliminary analysis of the student questionnaire data indicates a very positive response from students. Students agree that the in classroom use of mobile technologies: - made the module more enjoyable to attend – 86% - made the classroom sessions more interactive – 94.7% - had an impact on their motivation to study - 58.8% Page 5 of 9 July 1, 2008 - was useful for feedback on their understanding – 77.4% - gave them information about their understanding of components – 70.4% - had a positive impact on their understanding of the material – 75.4% - was a positive experience overall – 86.1% Students (51.7%) agree that the feedback they received assisted them in focusing their study efforts. Students (83%) would like other lecturers to use the technologies in their modules and 93% of the students would advise their lecturer to keep using the technologies. Written comments from students confirm that the use of mobile technologies was a positive experience. When asked if there was anything else they wanted to share with us about the use of the new technologies, they wrote: - “Innovative and enjoyable to use.” - “PP vote seems to allow students to show which aspect of their course they truly understand.” - “I found it enjoyable, caused more interaction in lectures.” - “The interaction in lectures was a good use of involvement / interaction with the subject content and helped aid learning.” - “I think it was a good valuable use of learning resources. I felt it aided my understanding and what I need to improve in the study.” Students were also asked for suggestions for improving the use of the new technologies in this module. Several students suggested using the technologies more frequently. “Technology was not used in all lectures, it should be as it was very helpful and interesting.” A number of students mentioned the fact that setting-up the technologies is time-consuming and advise staff to set the technology up prior to the sessions. “If the new technologies are going to be used they should be already placed in the seating area before lecture starts as it wastes unnecessary time handing them out.” A few students also commented on the unreliability of the technologies. “System didn’t seem to work sometimes.” Future Plans Page 6 of 9 July 1, 2008 Continuation of the project - Our evidence to date shows the important role that the two staff mentors played in supporting the participants and it is hoped to continue with this model next academic year with a number of this year’s participants acting as mentors. With a minimum of 6 mentors supporting up to 30 staff participants next year it is expected that a significant impact can be made in each faculty in terms of enhancing face-to-face learning and overall blended learning models. Ongoing Technical support - The project funded technical support for the classroom technologies used and the University has agreed to continue funding this post for the next academic year. This will allow us to continue to provide a support infrastructure for the mobile technologies. During the period of the project the University has expanded the number of mobile technologies that are available for learning and teaching. In November 2007 the University opened a ‘Collaborative Learning Zone’ as a student centred learning space supporting group work and activities. This room has been equipped with both an electronic voting system and a set of 15 tablet PCs. It is hoped to continue to expand the technologies available. In September each faculty will begin the second year of their blended learning strategy implementation. Over the summer the project team will analyse the project data and findings will be disseminated internally to the faculties to help inform this ongoing process and help shape faculty developments. Staff development events on the integration of mobile technologies into the classroom have been built into Academic Development’s staff development programme for the next academic year with a series of online resources either developed already as part of the project or are under development. We will continue to evaluate the role of new mobile technologies in learning and teaching and will apply for further project funding as appropriate. We are already investigating the use of mobile phone technology to provide ubiquitous voting systems and the use of low cost computing systems in combination with mobile broadband to provide networked computing in ‘any’ location such on fieldtrips etc. Great emphasis will be put on external dissemination as well, both by presenting at national and international conferences and through the submission of papers in refereed journals. Page 7 of 9 July 1, 2008 Key Messages for the Sector Embedding pedagogic change on an institutional scale is a complex task and it is recognised that the HEFCE eLearning strategy strand 1.4 ‘Produce and disseminate models of good e-learning practice including assessment’ is particularly relevant to this project. This project has demonstrated on evidence to date that a focussed limited scale project can be a significant catalyst for change especially where the project is closely linked to institutional strategy, is sustainable, the participants are well supported and that there are clear channels of dissemination. A number of focussed limited scale projects running in parallel may provide an effective approach to embedding institutional change. This approach will be continued at Kingston University during the next academic year as part of suite of targeted approaches to support the implementation of blended learning across the institution. In terms of specific points with regard project support the following points can be made: - the role of staff mentors with recognised expertise in the relevant field was effective. The mentor CAMEL groups also enabled staff to exchange experiences and advice on a regular basis. - the provision of dedicated technical support for mobile technologies proved essential to maintain the equipment and provide support for staff. Unreliability can be a significant issue in terms of continued use by staff and acceptance by students. Due to the portable nature of the equipment it was subject to more wear and tear and the need, for example, to replace batteries on a regular basis. The ability for academic staff to call for advice / troubleshooting support while setting up the portable equipment in a pressurised situation with students present proved valuable. In terms of the in-class use of mobile technologies, based on the analysis of our evidence to date, they have been effective by: - promoting greater interaction - enhancing feedback for both students and staff, and allowing staff to adapt their teaching based on this feedback. - acting as catalysts for change in learning and teaching approaches. It is obvious to state that technologies continue to evolve rapidly but it is important to recognise that some technologies in use today could be considered relatively expensive interim solutions and this should be considered when assessing Page 8 of 9 July 1, 2008 costs and benefits. Just over the period of the project the price of low cost mobile computers has dropped significantly as has that of mobile broadband. This has significant implications for ubiquitous networked mobile computing and its impact on learning and teaching. References Boyle, J. T., & Nicol, D. J. (2003). Using classroom communication systems to support interaction and discussion in large class settings. Association for Learning Technology Journal (ALT-J), 11 (3), 43-57. Cue, N. (1998). A universal learning tool for classrooms? Paper presented at the First Quality in Teaching and Learning Conference, Hong Kong. Dibattista, D., Mitterer, J.O., & Gosse, L. (2004). Acceptance by undergraduates of the immediate feedback assessment technique for multiple-choice testing. Teaching in Higher Education, 9 (1), 17 – 28. Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Draper, S. W., Cargill, J., & Cutts, Q. (2002). Electronically enhanced classroom interaction. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 18 (1), 13-23. Elliott, C. (2003). Using a Personal Response System in Economics Teaching. International Review of Economics Education, 1 (1), 80-86. Hake, R. R. (1998). Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: a sixthousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics, 66 (1), 64–74. HEFCE (2006). National Student Survey. Retrieved February 13, 2007 from http://education.guardian.co.uk/students/tables/0,,1574402,00.html. Masikunas, G., Panayiotidis, A., & Burke, L. (2007). The Use of Electronic Voting Systems in Lectures within Business and Marketing: A Case Study of their Impact on Student Learning. ALT-J, Research in Learning Technology, 15(1), 3-20. Nitko, A.J. (1996). Educational assessment of students. (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Merrill. Russell, M., & Haney, W. (2000). Bridging the Gap between Testing and Technology in Schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8 (19). Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Page 9 of 9 July 1, 2008