pms, eeg, and photic stimulation

advertisement

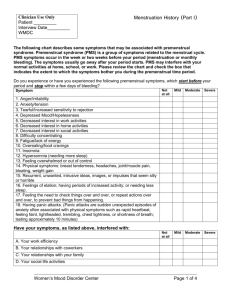

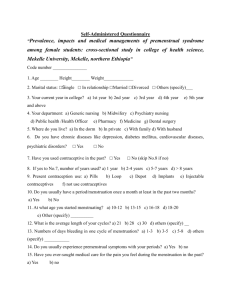

Preliminary trial of photic stimulation for premenstrual syndrome D. J. ANDERSON, N .J. LEGG and DEBORAH A. RIDOUT Department of Neurology and Medical Statistics Unit, Royal Postgraduate Medical School, London, UK Reprinted from Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (1997) Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 76-79. Summary In an open study 17 women with confirmed, severe and long-standing premenstrual syndrome used photic stimulation with a flickering red light, every day for up to four menstrual cycles. At the end of treatment prospectively recorded median luteal symptom scores were reduced by 76% (95% confidence interval 54-93, P<0.001), with clinically and statistically significant reductions for depression, anxiety, affective lability, irritability, poor concentration, fatigue, food cravings, bloating and breast pain. Twelve of the 17 patients (71%) no longer had the premenstrual syndrome. One patient failed to improve. One patient withdrew because of worsening premenstrual depression, but photic stimulation was otherwise well tolerated. The improvement is greater than that reported for relaxation or in open studies of fluoxetine, and much more than historical placebo rates. Photic stimulation may be a useful treatment for the premenstrual syndrome, and by its suggested action on circadian rhythms may have wider therapeutic applications. Introduction Premenstrual syndrome (Reid and Yen, 1981; Mortola et al., 1990; Bancroft, 1993), also defined as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), is a common disorder of unknown aetiology. Patients have a range of symptoms, physical, behavioural and psychological, which vary in intensity over the course of the menstrual cycle, disrupt normal functioning and are at their worst in the week before the menses. Current treatments include fluoxetine (prozac) which is better than placebo (Steiner et al., 1995), progesterone, which is not (Freeman et al., 1995), and other methods of altering the ovarian cycle, whose effects vary (Bancroft, 1993). Relaxation therapy was an effective treatment for severe cases in a controlled trial (Goodale et al., 1990). Photic stimulation can induce relaxation (Kroger and Schneider, 1959), and may therefore be of benefit. A portable variable frequency photic stimulation device, used in a previous study of migraine (Anderson, 1989), produced a significant reduction in premenstrual symptoms over 6 months in one subject who had obtained no relief from other measures. The purpose of this study was to quantify any beneficial effect of photic stimulation with flickering red light in a group of premenstrual syndrome patients, and to assess any effects on cycle length and dysmenorrhoea. Methods The study was open and was designed to follow 20 patients through a two-cycle baseline observation phase, a three cycle treatment phase and a final cycle off treatment. Patients were self-referred following local and newspaper publicity and were screened initially by a postal menstrual distress questionnaire (Moos, 1968) and a covering letter explaining the nature and demands of the study. Questionnaires (n = 261) were sent out and 82 were completed and returned. Patients were selected on willingness to participate, provisional confirmation of of the diagnosis based on the menstrual distress questionnaire and proximity to the study centre. Twenty-seven patients came for consultation, which included a full clinical history and examination. They were asked to choose their six most prominent and troublesome symptoms, including at least one physical symptom. They could use their own terms for instance 'mood swings' or 'angry outbursts' which were then assigned to the appropriate premenstrual dysphoric disorder category for analysis. In order to assess severity of symptoms they were supplied with diary cards, based on the PMT-Cator (Magos and Studd, 1988), and similar to an obstetric calendar, on which they could rate these 6 symptoms for up to 6 weeks. They were asked to record a score from 0 (no symptom) to 9 (as bad as it could be) for each symptom each day throughout the study. The luteal score was the sum total of the scores for each of the six symptoms for the 6 days prior to menses, and the follicular score the sum of the score from days 5 to 10 inclusive of the menstrual cycle. At each visit patients gave retrospective ratings of their previous cycle including a score of 0 to 9 for severity of dysmenorrhoea and a menstrual distress questionnaire. During the baseline observation phase three patients did not have cyclical changes of symptoms and were excluded. Three others withdrew, one because of pregnancy and two for personal reasons. The 21 patients entering the treatment phase satisfied all the criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and those of the National Institute of Mental Health (Bancroft, 1993) and Mortola et al. (1990) for premenstrual syndrome. All patients had a mean baseline luteal score above a severity threshold of 65 (representing 20% of the maximum possible score) (Freeman et al., 1995). No patient had history of epilepsy or concurrent psychiatric disorder, or was taking psychotropic drugs or hormones, including the oral contraceptive. They were aged between 23 and 44 years (median 38 years), had suffered from the syndrome for between 2 and 24 years (median 10) and had a menstrual cycle of between 24 and 34 days (median 28). They had taken a median of three previous treatments, without benefit. Seventeen patients completed at least two evaluable cycles on treatment. One patient moved abroad, one was lost to follow up, and one withdrew for personal reasons. One withdrew because of an increase in premenstrual depression, and did not return for further assessment. Fourteen patients completed the study by recording data for at least one more cycle on treatment and one cycle off treatment. The other three did not complete their diary cards for the third cycle and withdrew, all for personal reasons related to their employment. They did not stop treatment. Because of variations in cycle length and changes to appointments nine patients were treated for a fourth cycle. Thus there were data from 17 patients for the two baseline cycles and the first two treatment cycles, from 14 for the third treatment cycle, from nine for the fourth and from 14 for the follow up. Photic stimulation mask The photic stimulation mask is a portable photic stimulator delivering pulses of red light of wavelength 645 nm to each eye alternately at a frequency of 0.5 to 50 Hz and with a luminance of 10 to 45 mcd. A control box, which contains the control circuitry and battery is connected to miniature light -emitting diodes mounted in a neoprene wraparound face mask. Ambient light is excluded by close fitting hypoallergenic foam eyepads. Patients were instructed to use the photic stimulation mask daily, sitting comfortably with their eyes closed, with the frequency set at about the flicker fusion point, to increase the brightness to full and thereafter to adjust the frequency and brightness for the most comfortable setting, and to keep a record of the time and duration of mask use. Statistical methods Results are presented as medians and 95% confidence intervals (Altman, 1991) as we wish to make no assumptions about the distribution of the data. The Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test (Altman, 1991) was used to compare diary card scores, menstrual distress questionnaire scores and other variables. Results The median luteal scores for the two pre-treatment cycles did not differ so the mean score for the two cycles was used in subsequent analysis. The median baseline luteal score was 196 (95% confidence interval, 150-249). This was higher than the follicular score of 13 (0-17; P<0.001). The median follicular scores did not vary from the baseline throughout the study. After the first cycle of treatment the median luteal score fell from 196 (150-249) to 71 (41-136); P<0.001). Improvement continued with a further fall to 25 (8-139) by the fourth cycle, a reduction compared with the first treated cycle (P<0.05). At this point no difference was found between the median follicular and luteal scores. When treatment was withdrawn the median luteal score rose very little. The median reduction in luteal score for individual patients was 64% (54-93) after one cycle of treatment, and 76% (54-93) at the end of treatment. The three patients who withdrew after treating two cycles had individual reductions in luteal score of 82%, 91% and 53%, comparable with those in patients who completed the trial. After the first treated cycle there were reductions in the individual luteal symptom scores for depression, anxiety, affective lability, irritability, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, change in appetite, breast tenderness and bloating (P<0.05), and possibly for social withdrawal (P=0.06). There was insufficient data for separate analysis of the premenstrual dysphoric disorder symptom categories 'hypersomnia and insomnia' and 'being out of control'. In the last treated cycle there was a suggestion of further improvement in all symptoms except breast tenderness. At the end of the treatment only one patient had a luteal score higher than the baseline. Thirteen of the 17 patients had a reduction of the luteal score of at least 50%, and 10 of these had a reduction of at least 75%. Twelve of the 17 patients no longer met the criteria for the premenstrual syndrome. A substantial reduction in retrospective menstrual distress questionnaire scores of 74% (66-83) was seen after one cycle of treatment compared with the baseline (P<0.001), with physical symptoms responding similarly. No differences were found in the median cycle length, days menstruating, or menstrual flow between baseline and treatment cycles. The median dysmenorrhoea score was reduced from 5 (4-8) at the baseline to 3 (2-4) at the end of treatment (P<0.01). The duration of dysmenorrhoea was reduced from 36 hours (24-48 hours) to 24 hours (2-24 hours); P<0.001). Both severity and duration tended to return towards pre-treatment levels on withdrawal of treatment. Compliance and treatment use Patients used the photic stimulation mask for a median of 17 minutes a day (range 11-29 minutes a day), missing one day per cycle (range 0-5) and using the mask between 21.00 h and 24.00 h on 70% of occasions. Discussion Women with severe and chronic premenstrual syndrome obtained considerable benefit from the use of photic stimulation with flickering red light. Ninety -four per cent of women responded and the median decrease in prospectively recorded symptom score was 76% (95% confidence interval, 54-93). There is no previous report of variable frequency photic stimulation as a treatment for the syndrome. This level of effect appears at least equal to that reported for the most successful of previous treatments. In a small open trial a gonadatrophin-releasing hormone analogue, injected daily, abolished ovarian cyclicity, and reduced prospectively recorded symptom scores by 76% (Mortola et al., 1991). Fluoxetine, 20 mg daily, reduced symptom scores by 55% in an open study (Rickels et al., 1990) and between 44% (Steiner et al., 1995) and 62 % (Wood et al., 1992) in placebo-controlled studies. An obvious question is whether the effect of photic stimulation represents a placebo response, and one can only observe that it is much larger than previously reported placebo effects. A placebo response of up to 94% is often quoted in premenstrual syndrome, but this refers to one trial in which 33 of 35 women initially responded to a placebo subcutaneous implant (Magos et al., 1986). Their improvement measured by the mean reduction in daily symptom scores, was only 20% which is within the 10% to 30% range of placebo responses observed in other studies (Deeny et al., 1991; Wood et al., 1992; Freeman et al., 1995; Steiner et al., 1995). Patients are less likely to respond to placebo if they have sought treatment for premenstrual syndrome before (Metcalf and Hudson, 1985) or if the condition is long standing (Deeny et al., 1991). By these criteria our current study group should be poor placebo responders. Also placebo effects tend to wane (Magos et al., 1986), and patients in placebo treated groups tend to withdraw because of lack of response (Steiner et al., 1995), neither of which occurred in this study. Two other possible mechanisms for the response to photic stimulation are relaxation and an effect on entrained rhythms in the brain. Photic stimulation or flicker has long been known to induce relaxation in normal subjects (Kroger and Schneider, 1959), and also to evoke mood changes (Walter and Walter, 1949). Patients described the mask as relaxing, presumably because they found frequencies, which evoked pleasant or neutral sensations. The two previous studies of relaxation therapy are difficult to interpret because of the way the data are presented. One showed a reduction in symptom score of less than 20% in 12 patients (Morse et al., 1991). In the other the reduction was 30% overall in 16 patients, and 58% in the seven patients with undefined 'high severity' premenstrual syndrome (Goodale et al., 1990). These reductions are less than that found in the present study, suggesting that photic stimulation may not act by relaxation alone. An alternative mechanism is an effect on entrained rhythms in the brain. In the syndrome there is an abnormal relationship between the internal circadian clock and the sleep-wake cycle, in the form of a phase advance (Perry et al., 1990). Partial sleep deprivation has therefore been tried as an experimental treatment, in a manner similar to that used for major depressive disorders, and produced an average reduction in premenstrual symptom score of 62% (Perry et al., 1995). The mammalian circadian clock is intimately connected with the visual system (Stain Malmgren, 1993), and in humans it can certainly be phaseshifted by normal indoor illumination (Boivin et al., 1996). Flicker can cause a distorted sense of time (Walter and Walter, 1949), implying a direct, though temporary, effect upon internal clocks. Photic stimulation may perhaps reset the circadian clock, restoring normal synchrony between internal biological rhythms and external entraining cues. Such a mechanism could explain the improved sleep quality which was spontaneously reported by some of our patients and also the persistence of therapeutic response after the withdrawal of treatment. The optimum frequency and brightness settings, if such exist, the optimum duration of use and time of day of use, and the relative merits of alternate eye or synchronous flicker were not addressed in this study. The two patients with the poorest response, were the only ones to use the photic stimulation mask at extreme settings, one at the dimmest illumination and the other at the highest frequency, of 50 Hz. This open study of photic stimulation in a small group of patients with severe premenstrual syndrome has shown a considerable therapeutic effect, but it has not been tested against placebo. If these results are confirmed the underlying mechanisms will be of considerable interest. Photic stimulation appears to be a simple and safe treatment and may have other applications. Acknowledgements We thank Professor D. F. Hawkins for critical review of the study proposal. This study was supported by Migra Ltd. The photic stimulation mask and its use are covered by US patent 5092669 and UK patent 2196442. [One author D.J.A is the inventor of the photic stimulator described and has a financial interest in Migra Ltd.] References Altman D. G. (1991) Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London, Chapman and Hall American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, pp. 715-718. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association. Anderson D. J. (1989) The treatment of migraine with variable frequency photostimulation. Headache, 29, 154-155 . Bancroft J. (1993) The premenstrual syndrome - a reappraisal of the concept and the evidence. Psychological Medicine, Suppl 24, 1-47 Boivin D. B., Duffy J. F., Kronauer R. E. and Czeisler C. A. (1996) Dose-response relationships for resetting of human circadian clock by light. Nature, 379, 540-542. Deeny M., Hawthorn R. and McKay Hart D. (1991) Low dose danzol in the treatment of the premenstrual syndrome. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 67, 450-454. Freeman E. W., Rickels K., Sondheimer S. J. and Polansky M. (1995) A double-blind trial of oral progesterone, alprazolam, and placebo in treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome. Journal of the American Medical Association, 274, 51-57. Goodale I. L., Domar A. D. and Benson H. (1990) Alleviation of premenstrual syndrome symptoms with the relaxation response. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 75, 649-655. Kroger W. S. and Schneider A. S. (1959) An electronic aid for hypnotic induction: a preliminary report. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 7, 93-98. Magos A. L., Brincat M. and Studd J. W. (1986) Treatment of the premenstrual syndrome by subcutaneous estradiol implants and cyclical oral norethisterone: placebo controlled study. British Medical Journal, 292, 1629-1633, Magos A. L. and Studd J. W. (1988) A simple method for the diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome by use of a self-assessment disk. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 158, 1024-1028. Metclaf M. G. and Hudson S. M. (1985) The premenstrual syndrome: selection of women for treatment trials. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 29, 631-638. Moos R. H. (1986) The development of a menstrual distress questionnaire. Psychosomatic Medicine, 30, 853-867. Morse C. A., Dennerstein L., Farrell E. and Varnavides K. (1991) A comparison of hormone therapy, coping skills training, and relaxation for the relief of premenstrual syndrome. Journal of Behavioural Medicine, 14, 469-489. Mortola J. F., Girton L., Beck L. and Yen S. S. (1990) Diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome by a simple, prospective and reliable instrument: the calendar of premenstrual experiences. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 76, 302-307. Mortola J. F., Girton L. and Fischer U. (1991) Successful treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome by combined use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and estrogen/progestin [see comments]. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 72, 252A-252F. Parry B. L., Berga S. L., Kripke D. F., Klauber M. R., Laughlin G. A., Yen S. S. and Gillin J. C. (1990) Altered waveform of plasma nocturnal melatonin secretion in premenstrual depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47, 1139-1146 Parry B.L., Cover H., Mostofi N., LeVeau B., Sependa P.A., Resnick A. and Gillian J.C. (1995) Early versus late partial sleep deprivation in patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder and normal comparison subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 404-412. Reid R. L. and Yen S. S. (1981) Premenstrual syndrome. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 139, 85-104. Rickels K., Freeman E. W., Sondheimer S. J. and Albert J. (1990) Floxetine in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Current Therapeutic Research, 48, 161-166. Stain Malmgren, R. (1993) Biological cycles. In: The Headaches, edited by J. Olesen, P. Tfelt-Hansen and K. M. A. Welch, pp. 137-143. New York, Raven Press. Steiner M., Steinberg S., Stewart D., Carter D., Berger C., Reid R., Grover D., and Streiner D. (1995) Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria. Canadian Fluoxetine/Premenstrual Dysphoria Collaborative Study Group [see comments]. New England Journal of Medicine, 332, 1529-1534. Walter V. J. and Walter W. G.(1949) The central effects of rhythmic sensory stimulation. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 1, 57-86. Wood S. H., Mortola J. F., Chan Y. F., Moossazadeh F. and Yen S. S. (1992) Treatment of premenstrual syndrome with fluoxetine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 80, 339-344. Correspondance to: Dr. D. J. Anderson, Department of Neurology, Royal Postgraduate Medical School, Du Cane Road, London W12 0NN, UK.