Picasso- Guernica Painting

advertisement

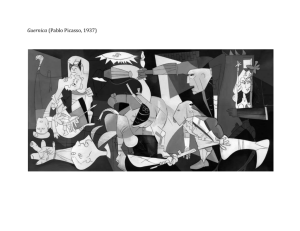

Picasso – Guernica Painting On April 26th 1937, a massive air raid by the German Luftwaffe on the Basque town of Guernica in Northern Spain shocked the world. Hundreds of civilians were killed in the raid which became a major incident of the Spanish Civil War. The bombing prompted Picasso to begin painting his greatest masterpiece... Guernica. The painting became a timely and prophetic vision of the Second World War and is now recognised as an international icon for peace. Despite the enormous interest the painting generated in his lifetime, Picasso obstinately refused to explain Guernica's imagery. Guernica has been the subject of more books than any other work in modern art and it is often described as..."the most important work of art of the twentieth century", yet its meanings have to this day eluded some of the most renowned scholars. Four years research into an unauthenticated Picasso drawing of a crucifixion, dated 12 May, 1934, has provided a wealth of new information about Picasso's use of symbolism. The study has also led to some remarkable discoveries about Guernica... listed here are a few examples. Guernica's "Secret" Harlequins (Note – Harlequins are clowns) "Experts," now agree that Picasso practised a form of art-magic, linked to this was Picasso's Harlequin. In 1932 another famous twentieth century magician, C.G.Jung... recognised Picasso's Harlequin as an underworld character, a master of disguise associated with the occult. Picasso identified with Harlequin whom he also associated with Christ due to the character's mystical power over death. In Picasso's "secret" Guernica, he has invoked a number of unseen Harlequins to overcome the forces of death represented in the painting. This is the largest Harlequin, which is cleverly hidden behind the surface imagery. The outline of the face can be seen in the lines and background tones of the composition, the eyes and the tuft of hair to the right of the face are clearly visible. The Harlequin appears to be crying a diamond tear for the victims of the bombing. The diamond is one of the Harlequin's symbols and in Picasso's work it is a personal signature. Painters often rotate or invert paintings to check balance and stability in the composition. Picasso knew from this and from his Cubist experiments that sideways or inverted imagery could have a powerful subliminal effect on the viewer and give a work hidden meanings and magical secrecy. The next Harlequin is easily recognisable as the painting is rotated 90 degrees to the right. From this viewpoint, Harlequin's hat becomes obvious as the figure appears to look upwards at the sky as if in reference to the bombing. This is another Harlequin, seen by rotating the painting 90 degrees to the left. The outline of the face and traditional hat and mask make him identifiable. Picasso hid many magical images in his work by incorporating them sideways or upside down. Sometimes, as in this case, he placed other images over the top as camouflage. This fourth Harlequin has been concealed by inversion, which is a common technique of encryption in Hermetic magic. This Harlequin is identifiable by his triangular hat and serrated collar. He is constructed from components of Punch and Judy theatre. The hat is peaked with a crocodile's jaw and his square mouth and face when viewed the right way up takes on the form of a traditional puppeteer's theatre. The Crocodile and the Harlequin are common characters in Punch and Judy shows, their inclusion in Guernica stems from Picasso's love of puppetry which began before the turn of the century in Barcelona where he saw many such shows and even helped produce them with Pere Romeu at Els Quatre Ghats . The figure falling across the Harlequin's face which is often assumed to be a woman, in fact bears a strong resemblance to Picasso, who appears to be identifying with the victims of the bombing. The next Harlequin (clown-like) image is again inverted and can be seen to the right of the previous Harlequin. He is identifiable from his patchwork costume and triangular hat and appears to be kneeling on the ground as if watching the puppet show taking place opposite. Guernica's Hidden Images of Death The preoccupying theme of Guernica is of course death; reinforcing this, in the centre of the painting is a hidden skull which dominates the viewer's subliminal impressions. The skull is shown sideways and has been ingeniously overlaid onto the body of the horse, which is also a death symbol. The skull's mechanical appearance seems appropriate to the modern weaponry used in the 1937 bombing. Picasso often hid one or more related symbols within a particular image as seen here. Below the dying horse in the centre of the painting is a concealed bull's head contained in the outline of the horse's buckled front leg. Its location infers that it is plunging its horns into the horse's belly from below... the goring of the horse in the bullfight was a favourite subject for Picasso and has strong sexual overtones. This image, like the concealed caricature of Hitler (not discussed in this article) was first identified by Mel Becraft, the inspired Guernica scholar and author of "Picasso's Guernica, Images within Images" Picasso remained neutral during the Spanish Civil War, World War I and World War II, refusing to fight for any side or country. Picasso never commented on this but encouraged the idea that it was because he was a pacifist. Some of his contemporaries though (including Braque) felt that this neutrality had more to do with cowardice than principle. As a Spanish citizen living in France, Picasso was under no compulsion to fight against the invading Germans in either world war. In the Spanish Civil War, service for Spaniards living abroad was optional and would have involved a voluntary return to the country to join either side. While Picasso expressed anger and condemnation of Franco and the Fascists through his art he did not take up arms against them. He also remained aloof from the Catalan independence movement during his youth despite expressing general support and being friendly with activists within it. No political movement seemed to compel his support to any great degree, though he did become a member of the Communist Party. During the Second World War, Picasso resided in Paris when the Germans occupied the city. The Nazis hated his style of painting, so he was not able to show his works during this time. He retreated into his studio, continuing to paint all the while. While the Germans outlawed bronze casting in Paris, Picasso was still able to continue because of the French resistance who would smuggle bronze to him. Comparisons There are so many similarities between 1934 drawing and Guernica that it seems certain to be an important but unknown precursor to Picasso's greatest painting. Like the drawing, Guernica is also full of hidden images and themes, consequently, almost every line and shape in it is meaningful, either in the context of what it represents or what it is concealing. The themes of death, the bullfight and the crucifixion are common to both pictures. The Guernica bull is very like the bull in the drawing, both are huge, in profile and stand motionless observing the scene before them. There is a strong similarity in the dramatic clashing of light and dark tones and the overhead light sources in both pictures. In both Guernica and the 1934 drawing there is a second bull's head concealed below the horse. The head of the woman with the lamp in Guernica swoops downwards from the upper right corner in exactly the same way as does the head of the hidden Lucifer in the drawing. Lucifer means 'the light bringer' and is related symbolically to Venus, the Morning Star. She represents the evil of the physical world. The fallen warrior in Guernica is very similar to the central figure in the 1934 drawing, both are in the crucifixion pose and both have severed arms, identifying them symbolically with Picasso. The fallen warrior, like the central figure in the drawing, is also relatable to Parsifal, because of the broken sword in his hand. Parsival was given a magnificent sword which breaks in two at a crucial moment in battle. In the centre of Guernica there is a human skull concealed within the body and legs of the wounded horse. Both pictures contain the same overlaying of horse and skull in the centre. In Guernica the horse has been stabbed by a spear, a symbol representing Picasso-the first four letters of his name mean spear in Spanish. The diamond tip of the spear represents harlequin, who like Christ has a mystical power over death. The Guernica spear also has a relationship to the broad paintbrush in the 1934 drawing. This has been overlaid on to the skull within the area of the concealed horse. In Guernica we find the skull penetrated by a spear within the horse. Picasso would have certainly made the association between a wet paintbrush and a spear in his childhood. Therefore it seems plausible from the placing of the paintbrush in the 1934 drawing, that the Guernica spear, is also a cryptic representation of Picasso's paintbrush, partly because of its similar appearance and partly because of its connection to Picasso's remarks about painting being a weapon, 'No, painting is not made to decorate apartments. It’s an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy.' The Guernica spear penetrates a cryptic representation of Hitler in the centre of the composition. In the centre of the 1934 drawing there is also a concealed portrait of Hitler. In the 1934 drawing, Picasso takes possession of the spear from Klingsor, who is strongly associated with Hitler. In Guernica, the artist continues this Wagnerian narrative by stabbing Hitler with the spear, which has now been transformed into a talisman of Picasso's personal mystical symbols. Picasso was very secretive about the meanings of Guernica and would only talk about it in a guarded and superficial way, yet the mysteries of its imagery have given rise to more art historical interpretations than any other picture in history. Surprisingly, nearly all of these scholarly interpretations are oblivious to Guernica's concealed imagery.