An Inaugural Professorial Lecture by Dr. Benjamin Dwyer, Professor

advertisement

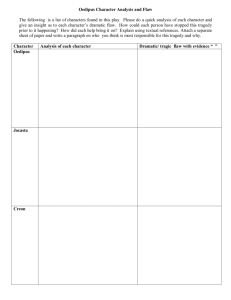

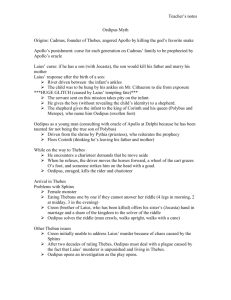

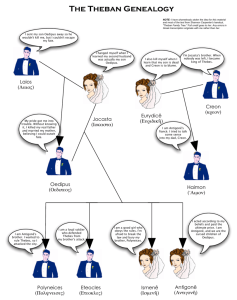

An Inaugural Professorial Lecture by Dr. Benjamin Dwyer, Professor of Music ‘Excavating the Irrational: Gender and Tragedy in Music’ (Reflections on the chamber work Umbilical by Professor Benjamin Dwyer) With a performance of Umbilical given by Maya Homburger - Baroque Violin Barry Guy - Double Bass David Adams - Harpsichord Thursday 28th February 2013 Middlesex University Grove Building – G274 The Burroughs Hendon London NW4 4BT Event Schedule Grove Building II - G274 4:30pm - 5:30pm Grove Building II - G274 Introduction by Melvyn Keen Deputy Chief Executive of Finance and External Relations followed by Dr. Benjamin Dwyer’s Inaugural Professorial Lecture 5:30pm – 5:45pm Break 5:45pm - 6:45pm Grove Building II - G274 Recital in the Concert Room 6:45pm - 7:15pm Grove Building, Atrium, 2nd Floor Mezzanine Buffet and Drinks Lecture ‘Excavating the Irrational: Gender and Tragedy in Music’ (Reflections on the chamber work Umbilical by Professor Benjamin Dwyer) RECITAL Maya Homburger – Baroque violin Barry Guy – double-bass David Adams – harpsichord Umbilical 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) 9) Laius Exorkismos Oedipus Eros Plēge Abyssos Agon Thanatos Epitaphion (harpsichord and tape) (violin, double-bass and harpsichord) (double-bass and tape) (violin, double-bass and harpsichord) (violin, double-bass) (violin and tape) (violin, double-bass and harpsichord) (violin, double-bass) (violin, double-bass and harpsichord) Based on Oedipus the King, Sophocles’s version of the myth, Umbilical circumvents textuality, telling the story through music. From the very beginning, I wanted to foreground the perspective of Jocasta—Oedipus’s mother and lover. In this manner, I hoped to both intervene in an established ‘grand narrative’ and present a work tackling issues around female agency, sexuality and immanence—aspects with continued resonance in contemporary society. The title Umbilical is apposite, as the umbilical cord is the connective tissue linking mother, father, and sonlover. I wrote the music so it would carry the narrative of this new ‘version’ of this well-known myth. In order to excavate the fundamental aspects of plot and character, I reduced the dramatis personae to three—Laius, Oedipus and Jocasta. By apportioning an instrument to each character— violin (Jocasta), double-bass (Oedipus) and harpsichord (Laius)—and writing solo pieces with tape for each instrument, the music reinforces characterisation and plot. In order to make evident Jocasta’s role as protagonist, I wrote music that intensively chronicles her psychological and emotional states as they shift and transform throughout the course of the story. Laius: This is introductory music. Laius, king, father of Oedipus and husband of Jocasta, is a spectre. He has been killed by Oedipus at the crossroads outside Thebes, but his character haunts the play. Until his killer can be found, the plague will continue to blight the city. Exorkismos: Jocasta attempts to extract herself psychologically from Laius. The Oracle had told Laius that if he had a son, the son would kill him. The marriage between Laius and Jocasta was, therefore, sexless, as Laius was avoiding this fate. Frustrated, Jocasta seduced Laius while he was drunk, thereby conceiving Oedipus. This scene is situated around the effects of Laius’s denial of Jocasta’s sexuality. Jocasta engages in a psychological ‘exorcism’ of her dead husband, thus making way for her virile new lover—Oedipus. Oedipus: This music suggests Jocasta’s projection of a new sexual awakening. Not knowing that her lover is, in fact, her son, she imagines and indulges in the possibility of a new, more sexually fulfilling life. The music, however, has dark overtones—with this new lover comes hidden and unknown dangers. Eros: This movement portrays the consummation of the sexual union between Jocasta and Oedipus. Tentative at first, the solo violin suggests Jocasta’s seductive advances. The brittle harpsichord indicates Laius’s continued presence in the background. But it is the entry of the double bass that initiates joy and pleasure. The movement unfolds towards unfettered sexual bliss. Plēge: This music provides the setting of the Oedipus story. Plague is visited upon the city of Thebes because the murderer of Laius (Oedipus) remains housed within the city-state. The music suggests a rat infestation, a viral explosion. The plague brings our attention to the role of the gods and the role of the city in this myth. I wanted to focus attention on the societal taboo of incest—Jocasta’s and Oedipus’s sexual aberration—the use only of violin and double bass and the further use of ‘their’ voices (recently heard in Eros) suggests their role in the blight on the city. Abyssos: Now cognizant that she has transgressed a fundamental taboo in having sexual relations with her son, Jocasta faces the abyss. Agon: Following on from Abyssos, Jocasta confronts the agony of her fate in the wake of her transgression. Thanatos: The tragedy is played out at this point: the rule of the city has been broken, Oedipus is shown to be his father’s murderer, Jocasta dies, and Oedipus gouges out his eyes with the metal pins that hold her dress. The instruments, which begin in unison, diverge throughout the work, portraying the separation of Jocasta from Oedipus in death (thanatos). Epitaphion: This movement acts as a précis of the entire story, in particular Jocasta’s painful psychological journey. Central to all Greek tragedy is the notion of peripeteia—that moment in a play when nothing will ever be the same again. Some have described it as a conversion of one state of affairs to its opposite. In Oedipus the King, this is the moment when the Oracle’s revelation that Oedipus had killed his father and married his mother brought about the latter’s death and his own blindness and exile. In the music, Jocasta is exponentially projected towards her fate. The knowledge of her transgression creates the peripeteia—this is suggested in the moment of sheer chaos in the music. All rationality has broken down. The punishment has far exceeded the crime. What is left is tragic aftermath. Professor Benjamin Dwyer As a prolific composer, a virtuoso guitarist and an innovative researcher, Benjamin Dwyer's creative and critical work extends from a broad base in performance and artistic practice. Dwyer has given concerts worldwide and has appeared as soloist with the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra, the Irish Chamber Orchestra, the RTÉ Concert Orchestra, the Neubrandenburg Philharmonic Orchestra (Germany), the Santos Symphony Orchestra (Brazil), VOX21, the Vogler String Quartet (Germany) and the Callino String Quartet (UK). He is a recipient of the prestigious Villa-Lobos Centenary Medal and the McNamara Gold Medal for Excellence. His latest CD (with the Callino Quartet UK), Irish Guitar Works, was released in 2012. Dwyer’s compositions are performed internationally, and he has been the featured composer at the Musica Nova Festival 2008 in São Paulo, the Bienalle of Contemporary Music of Riberão Preto 2009 (Brazil), the National Concert Hall’s Composers' Choice (Ireland), and the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra's Horizons series (Ireland). In recent years, he has completed a number of large-scale works. These include Scenes from Crow (a chamber work based on the Crow poems of Ted Hughes), Rajas, Sattva, Tamas: Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra, his ground-breaking Twelve Études for guitar, and Concerto No. 2 for Guitar and Orchestra, which he composed for the distinguished Brazilian guitarist Fabio Zanon. He has written works for a number of renowned soloists, including violist Garth Knox, pianist Ortwin Stürmer, saxophonist Kenneth Edge, and guitarist Craig Ogden. Dwyer is an elected member of Aosdána, the affiliation of creative artists established by the Arts Council of Ireland to honour those artists whose work has made an outstanding contribution to the arts. In 2009, he was made an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music, London (ARAM), and an honour bestowed upon those former students deemed 'to have made a significant contribution to the music profession'. He earned a PhD in Composition from Queen's University (Belfast), and MMus in Performance from the Royal Academy of Music (London), and a BMus (Hons) from Trinity College (Dublin). Professor Benjamin Dwyer