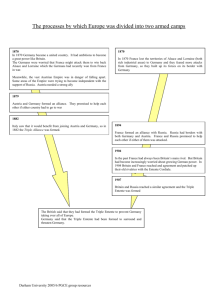

Bismarck's alliance system

advertisement

BISMARCK’S FOREIGN POLICY AND THE FRAMING OF THE EUROPEAN ALLIANCES, 1871-1907 Much of Bismarck was concerned with developments in Germany, his main interest after 1871 was still in foreign affairs. The German Empire had been built largely by his skill in diplomacy, and by that same skill he expected to preserve it. The central problem was the attitude of France. It can be argued that Bismarck in 1871 made a fatal mistake by annexing Alsace and Lorraine and so perpetuating France’s enmity. This was an injury that France intended neither to forgive nor to forget. The resources of the two territories in coal and iron, however, and above all their strategical value for the defence of south-west Germany against a new French attack, meant so much to Germany that Bismarck resolved to risk the undying hostility of France and take them. In so deciding he reckoned on three things. The first was that France would take many years to recover from the Franco-Prussian War. The second was that he could use the bogey of a French war of revenge to make the Reichstag maintain a high level of German armaments. And the third was that his diplomatic genius could keep France isolated – i.e. without any important ally. The first calculation was soon upset by the swiftness of France’s recovery. The £200,000,000 was paid off in two years, the army of occupation had to be withdrawn, the Republic was established as a permanency, and France seemed to be pulling herself together again. Bismarck was furious at the speed of all this (though he supported the establishment of a republic, which he thought would have more difficulty in finding allies than a monarchy). Accordingly in 1875, when France had begun to reorganize her army and increase her armaments, Bismarck indirectly threatened war – not in so many words, but in the form of hostile articles “inspired” in newspapers. He was certainly not the man to shrink from hitting an opponent as yet imperfectly on his – or her – feet. Nevertheless his object was probably only to bully France into abandoning her arms programme. In this, for once, he was unsuccessful, as both Britain and Russia reacted sharply against the apparent threat to France. They would not allow the balance of power to be completely upset by the annihilation or further weakening of France; and a visit to Berlin by the Tsar and a letter to the Emperor William from Queen Victoria clinched the matter. Bismarck found himself dealing with three powers, not one – and just as he knew the moment for attack, so he also knew the moment for retreat (and denial). The attitude of Russia over this incident disappointed Bismarck. Friendship with Russia had always been a mainspring of his policy. He had made it easy for the Russians to suppress the Polish revolt in 1863 and had been rewarded when the Russians remained neutral in the Franco-Prussian War. Immediately following that, in negotiations and meetings in 1872 and 1873, he had brought together the heads of the three great Empires – Germany, Russia and Austria-Hungary – in a pact usually known as the Dreikaiserbund (League of the Three Emperors) based on general friendship and consultation between the three powers. All three were conservatively-inclined monarchies, and all three had a common interest in opposing such ventures as Karl Marx’s “International” of working men (which they agreed to denounce). Bismarck also hoped, however, that this league of monarchical friendship, though somewhat vague, would form a common bond against republican France (which was one reason why he wanted France to remain a republic). Now, after Russia’s behaviour in 1875, it was clear that the policy of the three empires was very far from identical, and that the sentimental ties of the Dreikaiserbund might not count for much. -1- So indeed it proved a year or two later when the Eastern question entered one of its acute phases. It will be remembered that in 1877 after the Russian defeat of Turkey, Disraeli, being at length assured of the support of Austria-Hungary, by a threat of war compelled Russia to present the treaty of San Stefano to a Congress of European powers for revision. That Congress met, as we have seen, at Berlin in 1878, where Bismarck played the part of “honest broker” between Russia, Britain, and Austria-Hungary. At the Congress of Berlin Bismarck saw clearly that Russian and Austrian ambitions in the new Balkan states might well be incompatible, and that he might have to choose between Germany’s two friends. Bismarck’s choice fell on Austria-Hungary. He had at least three motives, quite apart from the fact that the Austrian core of the Hapsburg empire was German and that Russia was aggrieved by Germany’s failure to support her at the Congress. Possibly his main motive was that an alliance with Russia would confront Germany with the hostility of Britain, a power profoundly anti-Russian. Secondly, he knew that he could control Austria-Hungary and be the predominant partner in that alliance, whereas the position would be much more doubtful with Russia. Thirdly, the support of Austria-Hungary would leave open the Danube, the main trade route to the Mediterranean, and allow Germany considerable influence in south-eastern Europe. These three considerations and the fear of seeing Russia in control of Constantinople more than outweighed the danger of a hostile power on Germany’s eastern boundary. Moreover, though he was now choosing an Austrian alliance Bismarck had no intention of being involved in war with Russia if he could possibly help it. The upshot was that in 1879 Germany and Austria-Hungary concluded what became known as the Dual Alliance, an arrangement by which each party undertook to help the other in the event of an attack by Russia, or to keep neutral in the event of an attack by any other power (France, for example). This, though purely “defensive” in form, gave Bismarck everything he wanted, for he knew how to make a German war of aggression appear the reverse, while if Austria-Hungary tried one for her own ends he could disown her. So the Dual Alliance was concluded, and its existence soon publicised – though not its exact terms, which remained secret until 1888. Continually renewed, it remained for the period preceding the First World War the firmest feature in the diplomatic world. Bismarck had not abandoned hopes of patching up his relationship with Russia, nor was he content with merely one ally. The Dual Alliance ensured that if war came again with France, Austria-Hungary would be neutral once more, as in 1870. But there was another power in Europe now, and on France’s borders – Italy. Accordingly, Bismarck drew Italy into his network. His technique was characteristic. He secretly encouraged French ambitions in North Africa, mainly to “divert” her from scheming to recover Alsace-Lorraine but also to bring her into collision with Italy, who had ambitions in the Tunis area. Moreover French expansion in North Africa would not improve French relations with Britain. In 1881 the French, reluctant to see an Italian colony established on the borders of French Algeria, took Bismarck’s hint and occupied Tunis. This threw Italy into the arms of Germany. The following year she joined the two powers of the Dual Alliance in a separate Triple Alliance. The terms of the understanding were again defensive, Italy having no obligation to support an aggressive policy on the part of Germany and Austria-Hungary. If she were attacked by France, however, she would have the help of the other two powers; and if France attacked Germany, Italy would come to the latter’s aid. Altogether Bismarck scored a considerable success in binding Italy to his system, for though her armed forces were not very strong she had a valuable friendship with Great Britain. Shortly afterwards he extended the network still further by including Rumania, which between 1883 and 1888 signed separate defensive treaties with all the Triple Alliance powers. -2- So Bismarck now had Austria-Hungary, Italy and Rumania as allies, and Great Britain not only friendly with Italy but on bad terms with France over North Africa – for the French occupation of Tunis was soon followed in 1882 by the British occupation of Egypt. The only danger of trouble for the Triple Alliance was if France, otherwise completely isolated, should come to an agreement with Russia. This danger, however, Bismarck had already skillfully forestalled, partly by playing on the natural objections of the Tsar to the most democratic country in Europe, and partly by persuading Russia and Austria-Hungary to revive the old Dreikaiserbund, this time in the form of a much more precise treaty. This was done in 1881, and the general arrangement then concluded – that none of the three powers would help a fourth power (France, for example) if war broke out between that power and any one of them – was renewed in 1884. So the possibility of a Franco-Russian alliance seemed to be banished, France had no friend in Europe, and Bismarck’s work was complete. It only remained to keep it so. About this time Bismarck’s whole conception of foreign policy began to be challenged at home by a movement which demanded colonies for Germany. Bismarck thought of Germany as a European power dominating the Continent; the Colonial school hoped rather for a Germany which would be a world power. It stressed the importance of colonies as sources of raw materials, markets for manufactured goods, creators of valuable positions for young men and outlets for surplus population. In this it linked up with the growing European movement known as imperialism – the belief that the acquisition of colonies would not merely be economically or strategically beneficial to the European power concerned, but would also be economically and culturally beneficial to the native peoples taken over. Bismarck himself thought rather of the dangers of a colonial policy – how it would call for a big navy, and how that would inevitably bring Germany into rivalry with Great Britain. And once Great Britain was on bad terms with Germany, France would be no longer “isolated”. She would have as her ally the greatest and richest empire in the world. These dangers, however, did not weigh with Germany as much as Bismarck would have wished. Germans, conscious of their new strength, were resentful when they saw Britain, with her great white dominions, her Indian Empire, her innumerable points of vantage from Gibraltar to Hong Kong, also picking up much of Africa. As a result, all infuriated Germans longed for similar movements. Even the despised France was quietly building up the second greatest colonial empire. To Algeria (settled in the reign of Louis Philippe) and her protectorates in Indo-China (initiated under the Second Empire and extended in 1884-85), she had added Tunis, whence she began to advance over the Sahara and Western Sudan. Little Belgium, too, was building up a valuable source of tropical products in the Congo; while Portugal and Holland still retained much, and Spain a little, of their old overseas empires. And all the time Russia was pressing relentlessly into the Caucasus and central Asia. So, not surprisingly, the German demand for colonies grew. It was exactly the kind of clamour most difficult for Bismarck to resist – a demand inspired not by liberalism but by patriotism. Reluctantly the old statesman, who later described himself as “no colonial man”, had to shift his ground and set about acquiring enough colonies at least to keep the Germans quiet. In 1884 Germany accordingly entered, as a late-starter, the fast-developing competition for Africa. She made off with the districts known as South-West Africa, the Cameroons, and Togoland. In 1885 she followed this by securing leases of extensive areas in East Africa – the beginnings of her colony of German East Africa (Tanganyika). Within a few years a million square miles of territory went to Germany without her so much as fighting a battle -3- for them. It was a good beginning, but she was still a long way behind. In entering the colonial sphere, Germany at first suffered no bad effects apart from some minor quarrels with Britain. These and similar troubles between other Powers led to an international Colonial Congress being held at Berlin to lay down rules for the future. The most important of these was that the Powers would recognize “effective occupation” as a title to possession. With this assurance, the “scramble for Africa” could then get going in earnest. Since France was at loggerheads with Italy over Tunis, Britain at loggerheads with France over Egypt, and Russia at loggerheads with Britain over the Balkans and the Far East, Germany seemed at first in a very favourable position. Her alliances gave her valuable friends, while her rivals’ objections to one another were greater than their common objection to Germany. Bismarck was like a clever juggler who could keep five very costly plates – Austria-Hungary, Italy, Russia, France and Britain – spinning through the air. The plates were always in some danger of being smashed and of injuring the juggler in the process, but Bismarck’ skill was such that the disaster never occurred. Consequently he earned much applause and enriched the employer for whom he worked. But sooner or later that employer had to give way to another- and what if the new employer himself should fancy his powers as a juggler (though he was quite an amateur) and want to try his own hand with the plates? This in fact was what occurred. Within a few years the new Emperor, successive Chancellors and the force of events brought about all the developments Bismarck had feared. Already during his own period of office he had found the task of keeping friendly with both Austria-Hungary and Russia extremely difficult. To maintain the friendship with Russia he had concluded in 1887, when the renewed Dreikaiserbund Treaty ran out, another agreement known as the Reinsurance Treaty. By this Russia and Germany promised to remain neutral if either went to war with a third power – except if Russia attacked Austria-Hungary or Germany attacked France. Now, freed from Bismarck’s control, the young Emperor followed other advice and allowed the Reinsurance Treaty to lapse. He did this because he was anxious to see Germany, not Russia, dominant at Constantinople, and because this would inevitably lead to trouble with Russia. His new advisers, being doubtful whether Russia would prove a reliable friend, at first inclined more to friendship with Britain – with whom, 1890, Germany made an agreement. By this she received Heligoland, which had been in British hands since the Napoleonic wars, in return for recognizing a British protectorate over the territories of the Sultan of Zanzibar. All this had a rapid effect on France and Russia. Germany, with Austria-Hungary and Italy already as firm allies, seemed to be stretching out the hand of friendship to Britain. France had for long been “isolated”: now Russia seemed to be isolated too. What more natural than that the two isolated powers should join together to end their isolation? The process did not take long. Even before Bismarck’s fall the publication of the Dual Alliance with Austria-Hungary had made Russia suspect the sincerity of Germany’s friendship, and further doubts had come when she found it hard, to raise loans in the Berlin money market. Now, in view of the German Emperor’s overtures to Britain, his refusal to renew the Reinsurance Treaty, and the renewal of the Triple Alliance in 1891, she began to feel certain of Germany’s unreliability. By contrast, she found France eager to cultivate her friendship – and fully prepared to raise big loans for her in Paris. So the two countries came together, in spite of the vast differences between Russian Tsardom and French democracy. By two or three stages a firm defensive military agreement was reached, the main feature being that -4- each would come to the other’s help if attacked by Germany. This was signed in 1892, and confirmed in 1894. So the Dual Alliance of France and Russia at length stood opposed to the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy. Bismarck’s haunting fear, “the war on two fronts” – against France and Russia simultaneously – loomed nearer. As yet, Britain still stood apart. In the early 1890s she certainly no nearer the Franco-Russian camp than she was to the Triple Alliance. Indeed, in coming together, France and Russia were conscious of their rivalries with Britain as well as Germany, for bad feeling persisted between Britain and France over Africa and between Britain and Russia over the Near and the Far East. For some years, in fact, the relations between France and Britain grew worse rather than better. France bitterly resented the British occupation of Egypt, while Britain objected to France’s protectorate in Tunis and her obvious designs on Morocco. Then, in the “Fashoda Incident”, a crisis blazed up over the Sudan. To counter the British occupation of Egypt the French had decided to control, if they could, the Upper Nile. One of their expeditions, led by Major Marchand with a handful of Frenchmen, spent two years of hardship winning its way across Africa from the Congo. Marchand at length reached the Upper Nile and planted the Tricolore at Fashoda, a small village on the river. A few days later Britain’s General Kitchener arrived on the scene following his defeat of the native Sudanese forces at Omdurman (1898), and found British control of the all-important Nile contested by a few individuals and the French flag. The matter was referred to the respective governments and for a time it seemed that the two countries were on the verge of war. Finally, however, France climbed down and acknowledged British control of the Upper Nile. Delcasse, the new French Foreign Minister, shrewdly calculated that British friendship might be more valuable to France than Fashoda or half a million square miles of the Sudan. It took some years for Britain to realize her need for friendship with France. For a time she seemed to be turning to Germany. The latter, however, increasingly jealous of British colonial and naval power, contemptuous of British liberalism, and fearful of being drawn into a clash between Britain and Russia, rebuffed Joseph Chamberlain’s friendly overtures. Gradually Britain’s outlook began to change. The hostility of almost every country in Europe during the Boer War was one factor – particularly that of Germany, whose Emperor had already in 1896 sent a telegram congratulating Kruger on repelling the Jameson Raid. Then there was the retirement from the post of foreign secretary of Britain’s foremost expert in foreign affairs, Lord Salisbury – a statesman whose policy has been described (not quite accurately) as one of “splendid isolation”. Any splendour which isolation held for Britain was now becoming less and less visible with each fresh cloud on the horizon. The passing of the old Queen, too, and the accession of Edward VII made some difference. Victoria had been pro-German, whereas Edward not only intensely disliked his nephew, the Emperor William II, but had a passionate fondness, understandable in view of his upbringing, for France and the French. The main factor, however, in swinging Britain against Germany was the increasing clamour in that country for a big navy and colonial empire. In 1895 the Kiel Canal connecting the Baltic and the North Sea was opened, essential if Germany were to become a major naval power. In 1898 and again in 1900 the Reichstag approved Navy Bills which laid the foundation of a great German battle fleet – the dream of Admiral von Tirpitz, by this time in charge of the German admiralty. Germany was already the strongest European power on land. It was not likely that Britain, whose navy had ruled supreme since the Napoleonic wars, would welcome a powerful rival in her own sphere of the sea. -5- In 1902 Britain took her first step away from isolation. She made an unexpected alliance with Japan, whose rapid westernization was the wonder, and not yet the dismay, of the world. Its declared object was to safeguard the independence of China and Korea – which meant, among other things, discouraging Germany, Russia and France from further “pickings” in the Far East. By its provision for neutrality if either signatory became involved in war in the Far East (or for active help if the war was with two or more powers), the Anglo-Japanese treaty made it possible for Japan to attack Russia, as she shortly did, without fear of outside interference. It also enabled Britain to keep more of her naval forces in Europe, in case of trouble with Germany. In 1904 the next and much more decisive step for Britain followed: the Entente Cordiale with France. The Entente, for which Delcasse worked with great skill, was not a military alliance but an understanding. In form it was a series of detailed agreements about zones of Anglo-French dissension, notably in North Africa. Here the terms were the obvious ones – that France recognized Britain’s predominant position and interests in Egypt, while Britain recognized France’s claim to a similar position (which she had not yet achieved) in Morocco. But although so limited in form the Entente was two years later followed by the first military discussions between the staffs of the British and French armed forces about how to deal with Germany, should that become necessary. Though the Entente was not an alliance in name, it soon became something rather like it in fact. At any rate Germany was offended by it, both because it seemed to shut her out of Morocco and because it announced some kind of Franco-British partnership. The Germans were not long in reacting to the new agreement. In 1905, while Russia was in turmoil at home and fighting Japan abroad, Germany seized the opportunity to put pressure on France. William II was sent by his ministers to Tangier, in Morocco, where he made a speech emphasizing Germany’s interests there and the importance of maintaining the Sultan’s independence. Germany then went on to demand the calling of an international conference to review the whole question of Morocco; and the French, in view of their Russian ally’s troubles, felt obliged to agree, despite the urgings of Delcasse, who resigned in protest. The conference duly met in 1906 in Algeciras, in Spain, but Germany got little backing for her views except from Austria-Hungary. Though they accepted that the future of Morocco was of international concern, and recognized trading rights for all and a special zone of influence for Spain, the French were able to emerge from the conference with a valuable gain – the acknowledged right to intervene as necessary to maintain order in the greater part of Morocco. This in effect meant the right to control its government. One fact which encouraged them during the negotiations was that, a few days after the conference opened, the British foreign secretary agreed to contacts between the British and French military staffs. With the Entente not only concluded but having survived its first test, France then set about ironing out the differences between her two friends, Britain and Russia. The main trouble, the conflicting aims of the two countries in the Middle East – Britain’s Far Eastern worries had been ended by Japan’s defeat of Russia in 1904-05 – was soon solved. In addition to forswearing expansion on the northern borders of India (in Afghanistan and Tibet) the Russians agreed to limit their sphere of influence in Persia to its northern part. Britain’s influence was declared to be predominant in the south, and a neutral “buffer” zone was left between. With Russian expansion in the direction of India and in the Far East checked, there remained only the historic question of the Russian advance in the Balkans. To this, however, Britain had ceased to attach so much importance, for the Balkan nations had shown their -6- independence of Russia. And if Russia did get to Constantinople it would be no worse than having Germany in control there, the latest ambition of William II. So the rifts between Britain and Russia were healed, and the Dual Entente became extended into the Triple Entente of France, Britain and Russia. By 1907 there was thus at last a substantial counterweight to the German-Austrian-Italian combination. Alongside, and possibly against, the Triple Alliance, now stood the Triple Entente. Bismarck, dead by 1898 after eight years’ bitter criticism of his successors, might well have turned in his grave at so dangerous a development for Germany. -7-