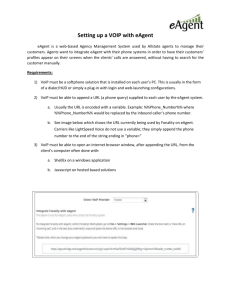

WirelessVoIP_5Oct2005

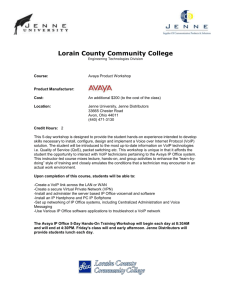

advertisement