Microsoft Word

advertisement

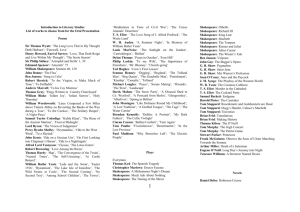

CHAPTER EIGHT BANVILLE’S IRISH COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE STEPHEN BUTLER POLITECHNIKA KOSZALINSKA In reviewing John Banville’s novel The Sea, which gained some notoriety by subsequently winning the prestigious Man Booker Prize, the drama critic Fintan O’Toole modified Walter Pater’s famous dictum that “all art aspires to the condition of music” with respect to Banville by claiming that “John Banville’s later novels aspire to the condition of painting” (17). The later literary criticism of Banville has kept pace with the later novels in this particular regard. John Kenny believes that all of Banville’s novels, not just the later ones, contain what he refers to as a “pictorial paradigm” (52-67). Joseph McMinn claims that the two preoccupations that Banville always returns to in his fiction are Science and Art, with the early novels showing a predominance for the former, with the later novels being dominated by the latter. McMinn refers to the later work as a “feminine counterpart to the earlier fictions”, but argues firmly that in both cases Banville is compulsively addressing himself to the same themes, much like his Irish predecessor Yeats who rhetorically asked himself late in life: “What can I but enumerate old themes?”. McMinn’s contention is that there is a “theatrical conceit which plays itself throughout Banville’s fiction, a conceit which suggests, not just the element of performance in text and character, but also the sense, held by so many of Banville’s narrators, that the world about them is a ‘staged’ imitation of Nature” (14). So, not only does Banville’s work aspire to the condition of painting, but it also aspires to the condition of the theatre, according to McMinn’s analysis. Medina Barco, Inmaculada (ed.): Literature and Interarts: Critical Essays. Logroño: Universidad de La Rioja, 2012, pp. 9-22. 9 BANVILLE’S IRISH COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE This was confirmed in the novel Eclipse, whose main character is a thespian named Alexander Cleave, which Banville published not long after McMinn’s study. The thematic concerns unique to Banville’s work, as indicated by McMinn, are also very much in evidence in this novel, but this should not be surprising given that the theatrical conceit is present in all of Banville’s fiction. However, the theatre is not just a conceit in Banville, it is another art form that he discusses with as much regularity as his twin obsessions of Art and Science, particularly in the later novels, and one that has not garnered much critical discussion in Banville’s oeuvre. The particular form of theatre that Banville dwells on obsessively is the Italian Comedy, or Commedia Dell’Arte, and it is the purpose of this paper to focus on the particularities of this art form, and how Banville uses it in connection with his other more obvious thematic concerns. The Italian Comedy was an improvisational form of theatre that flourished in Italy in the sixteenth century, and which may have descended from the medieval carnival, itself possibly connected with the ancient Roman Saturnalia festivals. It was a populist form of street entertainment, employing stock figures and scenarios for comic effect. It originated in the market place, where amateurs and professionals alike could draw the attention of the crowd, and attempt to make a living. Often, it was a theatre situated on the road, with the actors setting up wherever they thought they could draw a large enough crowd. Another reason why they were always on the move was to escape the restrictions, and at times persecution, of the civic and religious authorities. Due to this repression, and the derogatory attitude afforded it by the professional theatre, it didn’t survive long, and some locate its demise as far back as the eighteenth century (Rudlin, 10-26). It did, however, enjoy a significant rebirth in the twentieth century, mainly thanks to the efforts of theatrical directors, such as Edward Gordon Craig in England, Russia’s experimental innovator Vsevolod Meyerhold, Jacques Copeau in Paris, and the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Given the rather arch cultured image that Banville often portrays, with his frequent references, in particular, to the high modernists in literature such as Beckett, Rilke and Wallace Stevens, and in painting to classicists of the caliber of Poussin, Watteau and Rembrandt, it would seem surprising that he would have an interest in such a populist, socially-oriented form of discourse. However, it makes perfect thematic sense, given that the Commedia was often a subject of many of the painters often referred to by Banville (Figure 1). Watteau, in particular, had a strong affinity with the Commedia, and it may well have been influential in the creation of his own ‘fête galante’ style of painting. He often painted the figures from the Commedia, the most famous of which is his Pierrot. Banville uses both this painting and Watteau’s ‘The Embarkation of Cythera’ in his novel Ghosts (Figure 2). He does this in an attempt to achieve, according to 10 STEPHEN BUTLER McMinn, “a narrative version of a fete galante, drawing on the genre’s mythical symbolism and its love of theatrical artifice” (118). Figure 1. Jean-Antoine Watteau: “Love in the Italian Comedy” Figure 2. Jean-Antoine Watteau: “The Embarkation of Cythera” What Banville does in Ghosts is combine the two Watteau paintings to supply the narrative of the novel. There is no plot in the novel, as there rarely is in any Banville novel. Instead the novel describes the scenario painted by Watteau in ‘The Embarkation of Cythera’. The main character, art historian and former murderer Freddie Montgomery, has exiled himself to an island, seeking solitude, only to have this solitude interrupted by a group of people temporarily 11 BANVILLE’S IRISH COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE shipwrecked on the island. There is a very strong probability, though, that these people do not technically exist, and that Freddie is simply imagining the figures of Watteau’s painting into existence to entertain himself during his lonely occupation on the island. There are numerous hints that this is the case, as when Freddie states: “I was alone, despite the presence of the others […]. I know how this will seem: that I had retreated into solitude, that I was living in a fantasy world, a world of pictures and painted figures and all the rest of it” (68). The painted figures come from Watteau’s painting, which he in turn purloined from the Commedia Dell’Arte, and there is a particular figure that both the painter and novelist seem particularly interested in portraying. Freddie talks of how in the underworld, ghostly atmosphere of the novel most of the characters can be described as “Pierrots and Columbines in their black masks” (Figure 3). These are the two figures most often referred to in all Banville’s later novels, so it would seem pertinent to ask just what attraction these two stock characters hold for Banville. One of the interests would seem to be in the relationship between the two. Pierrot, throughout the Commedia tradition, is eternally infatuated with Columbine, which is never reciprocated, and so he “suffers eternally unrequited love” (Rudlin, 136). Love, whether requited or not, is not a theme normally associated with Banville, at least not by literary critics, although fellow novelist Patrick McGrath described the novel Athena, the successor to Ghosts with Freddie Montgomery as the main character again, as an “elegiac love letter” (24). It’s a fairly accurate description as the novel is addressed entirely from Freddie to his phantom lover, known only as A, with whom he has an intense passionate sexual relationship before she abandons him inexplicably. Freddie copes with the loss by writing the novel Athena, as he explains on the last page of the novel —“Write to me, she said. Write to me. I have written” (212). Figure 3. Maurice Sand: “Colombine” 12 STEPHEN BUTLER The relationship between Pierrot and Colombine is forever unrequited due to the fact that Colombine is herself in love with Arlecchino. Pierrot never has the opportunity to pursue a relationship with her, and even if he does the relationship is normally based on a deceit perpetuated by Colombine. The end result of this deception is always the same: “If she deceives him he blames himself for not being adequate as a lover” (Rudlin, 136). This could just as easily be a summary of the plot of Athena, as Freddie writes the entire novel to try and make sense of how it is he has failed A as a lover, even though he knows deep down that she left because she was involved with a group of criminals engaged in fraud, and they simply exploit Freddie for their criminal activities. The connection between love and deception implicit in the Pierrot/Colombine relationship is a common theme in Banville’s later novels. Often the deception is simply self-deception, as is the case with Freddie in Athena, and it illustrates a point about human relationships that Banville often addresses in his work. If Pierrot never really has a true relationship with Colombine, how can he possibly be in love with her, and what exactly is it that he is in love with, if he never really knows Colombine? He is in love with his own image of her, and as is often the case in Banville’s novels, his characters are more in love with painted images of women rather than actual women. Freddie actually defends this kind of relationship: after all it should be perfectly possible to ‘fall in love’, as they like to put it, with a painted image; after all, what is it lovers ever love but the images they have of each other? Freud himself remarked that in the passionate encounter of every couple there are four people involved. Or should it be six? —the two so-called real lovers, plus the images they have of themselves, plus the images that they have of each other. What a tangled web Eros weaves! (Ghosts, 87) In the Italian Comedy this truth about human relationships is often a source of amusement, and the stock characters of the lovers manifest this on the stage. As John Rudlin describes these stock characters: They relate exclusively to themselves —they are in love with themselves being in love. The last person they actually relate to in the course of the action is often the beloved. The Lovers love each other, yet are more preoccupied with being seen as lovers, undergoing all the hardships of being in such a plight, than with actual fulfilment. (108) 13 BANVILLE’S IRISH COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE As McMinn mentioned, in the ‘fête galante’ there is a love of theatrical artifice, and this is also true of the relationships shown on the stage of the Italian Comedy. The one thing the Lovers in this tradition know is that they are always being watched, and so they act accordingly (Figure 4). Figure 4. The Inamorato/The Lovers The “theatrical artifice” of the Italian Comedy manifests itself in a strikingly visual way —through the use of the mask (Figure 5). The mask creates the fixed types of the characters employed in this kind of theatre, sacrificing the idea of the personality of the actor in favour of the persona of the mask, defined by John Rudlin as a “metaphysical quality […] because it is of all times and all places, [it] readily overcomes personality, which is time and place specific. There is no point, therefore, in looking for values in commedia dell’arte which it cannot provide, such as psychological realism or comedy of manners” (34). Banville has often made similar comments about his own fiction, and it is difficult to find a Banville narrator who doesn’t profess an admiration for the theatrical mask. In The Book of Evidence, the first novel in which the reader is introduced to Freddie Montgomery, the narrator’s artistic credo is succinctly declared: “To place all faith in the mask, that seems to me now the true stamp of refined humanity. Did I say that, or someone else?” (16). The ‘someone else’ was Nietzsche, as the passage is really nothing more than a paraphrase of a crucial passage in Beyond Good and Evil. Nietzsche phrases it thus: “Everything profound loves the mask” (51). For Nietzsche, a 14 STEPHEN BUTLER profound, free, spirit is one that has realized that there is no ‘real’ self, or personality, to be revealed to others, that the self is persona, and nothing else. As a result, the free spirit is free to communicate with others using “silence and concealment” since others will simply create a false image of the spirit’s self anyway. In other words, the mask is always there in human relationships, whether personal or social. Freddie believes that this happens due to people’s selfconsciousness, when they know they are being observed, as is the case with the Lovers in the Commedia, who know that there’s an audience watching them, and act accordingly. When people know they are being watched, according to Freddie “something compels them to put on a mask and hide behind it” (32). Freddie is lucid enough to know that this involves what he calls “inauthenticity and bad faith”, a strategy fully endorsed by both himself and Nietzsche (Ghosts, 187-88). Banville purposefully introduces Sartre’s existential term here as in his fiction he introduces many situations that show the inadequacy of Sartre’s declamation to live authentically. There are situations in life in which living authentically is arguably not a recommended strategy; that concealment and “cunning” may be more suitable, since as Nietzsche remarked: “Something might be true although at the same time harmful and dangerous in the highest degree” (15). Such a situation is provided in The Sea, when the wife of the main narrator is about to receive the news that she’s dying of cancer. To simply blurt out such a harmful truth would be rather tactless, and so the doctor employs theatrical techniques to cushion the blow. Max, the narrator, is aware of this, and acquits the doctor of any sense of wrongdoing: “there was something studied about this hesitancy, something theatrical. Again, I understand. A doctor must be as good an actor as physician” (16). Figure 5. The masks of the Commedia dell’Arte 15 BANVILLE’S IRISH COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE Banville is indebted for this idea not only to Nietzsche but also to Diderot, another philosopher interested in masks. Allen Speight discusses how Diderot was aware of “the social ‘masks’ of an affected age and how they may successfully be worn” (82). Freddie Montgomery, whilst reading Diderot, comes to the same conclusion as the philosopher: “He conceived of living as a form of necessary hypocrisy, each man acting out his part, posing as himself” (Ghosts, 188). Specifically, Freddie is reading about “Diderot on actors and acting”, so it’s reasonable to assume that he’s reading Diderot’s The Paradox of Acting. In this text, Diderot believes that a successful actor should become a mere imitator who copies the appropriate gestures and responses that a given theatrical scene demands, without actually feeling the emotion of the situation. His justification for this is a pragmatic one: “If the actor were full, really full, of feeling, how could he play the same part twice running with the same spirit and success? Full of fire at the first performance, he would be worn out and cold as marble at the third. But take it that he is an attentive mimic and thoughtful disciple of Nature” (Diderot, 14). Freddie is not a professional actor, but Alexander Cleave in Eclipse is, and although he doesn’t seem familiar with Diderot’s theory, he has claimed to have read “Kleist on the puppet theatre” (Eclipse, 36). In this essay, the German dramatist Heinrich von Kleist discusses the same paradox of acting delineated by Diderot. Diderot believed that the best actor is a mimic, whilst Kleist believed that it was a puppet. The superiority of the puppet over a human actor lies in Kleist’s disquisition on “how consciousness can disturb natural grace” (Kleist). A puppet doesn’t possess consciousness, as it is inanimate, but even an animal is preferable to a human as an animal doesn’t suffer from the same self-consciousness exhibited by Freddie. To illustrate this, Kleist employs his famous description of the battle of wills between a man and a bear, which the bear wins rather easily due to its complete self-composure, a faculty that his human counterpart rapidly loses: the bear’s utter seriousness robbed me of my composure. Thrusts and feints followed thick and fast, the sweat poured off me, but in vain. It wasn’t merely that he parried my thrusts like the finest fencer in the world; when I feinted to deceive him he made no move at all. No human fencer could equal his perception in this respect. He stood upright, his paw raised ready for battle, his eye fixed on mine as if he could read my soul there, and when my thrusts were not meant seriously he did not move. (Kleist) The conclusion that Kleist draws from this story is that “in the organic world, as thought grows dimmer and weaker, grace emerges more brilliantly and decisively”. 16 STEPHEN BUTLER This is also the attraction of the use of the mask in the Commedia Dell’Arte. When an actor dons a mask, the self-consciousness of the personality disappears, leaving the impersonality of the persona, which is analogous to the impersonality of the puppet, as Efrat Tseëlon illustrates: “The mask is simultaneously animated and inanimate, living and dead: an expressionless mass transformed into expressive being. On its own it is a lifeless piece of matter, like the marionette without the puppeteer. But as soon as the mask is worn, or the marionette is pulled on a string, they come to life. Human interaction infuses them with spirit” (21). The paradox of the mask, however, is that when it is donned, it becomes unclear whether the mask is the marionette or the puppet. In Banville’s novels, the preference seems to be for the former. In other words, the people who inhabit Banville’s fictional universe are normally being controlled by their masks, not the other way around, or by a mysterious puppeteer who is never clearly identified. The reduction of the personality to a puppet is first touched on in The Book of Evidence, when Freddie attempts to explain how he has no control over any of his actions, subject as he is to “that puppet-show twitching which passes for consciousness” (34). In treating other people as similar puppets, Freddie has no qualms regarding the murder of another human being. There is an unpleasant psychological process that can occur when dealing with masks, known in psychology as ‘deindividuation’, which can be used to justify cruel behavior towards others, as explained by Tseëlon: “For many people their own anonymity or the facelessness of the other washes away all their humanity” (30). Freddie was able to murder a woman because she wasn’t sufficiently human, in his eyes. In Ghosts the painted figures he interacts with are referred to as “manikins in a window”, whilst in Athena his treatment of his lover A isn’t dramatically different from the way he viewed his earlier murdered victim, as on one occasion he asks himself: “What shall I dress my dolly in today?” (94). Freddie does not murder A, which is some form of improvement, but the nature of their sexual relationship indicates that Freddie hasn’t really evolved much from the earlier novel. He talks about the “shamefaced pleasure of voyeurism” that he takes both from his love of painting and his love of A, who herself is not innocent of this vice. Freddie compares his pleasure with that of “the triumphant female’s desire to be spied on by one lover while she lies in the arms of another” (Athena, 186). This describes perfectly A’s exhibitionist and perverse sexual tendencies that occupy a lot of the subject matter of the novel. She has no problem having someone like Freddie for a lover, who treats her like a doll, as “she had always wanted to have a fetishist for a lover” (94). This is another aspect of the process of deindividuation, which is again linked to masks, as explained by Tseëlon: “It applies to all masks used in ritual, theatre or carnival, even in sexual perversions” (20). It also applies to literature that has an obsessive relationship 17 BANVILLE’S IRISH COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE with paintings, a point that Edna Longley makes in her essay “No More Poems about Paintings”: “addiction to the practice (e.g. Wallace Stevens) can be a form of imaginative auto-eroticism” (94). Freddie certainly falls prey to this particular vice time and again throughout the trilogy of novels he narrates. His study of art history, and his obsessive engagement with different paintings blends, particularly in Athena, into his predilection for perverse sexual behavior and voyeurism. Even the supposedly objective pieces of art criticism he engages in in this novel gives way at the end to his perverse obsession with his lover A: “they all look like you: I paint you over them, like a boy scrawling his fantasies on the smirking model in an advertising hoarding” (152). Many actors perceive working with masks as a deindividuation of their personality. Rudlin mentions how many modern actors react against the improvisations of traditional Italian Comedy, due to their “firm basis of faultless technique”, which is seen to inhibit “creative freedom” (48). The paradox of acting though, as discussed by Diderot, Kleist and even Nietzsche, is that in focusing purely on technique, on mimicry, the self is actually expressed with more “creative power”. Kleist explains this paradox with the example of a dancer on stage: ‘Just look at that girl who dances Daphne’, he went on. ‘Pursued by Apollo, she turns to look at him. At this moment her soul appears to be in the small of her back. As she bends, she looks as if she’s going to break, like a naiad after the school of Bernini. Or take that young fellow who dances Paris when he’s standing among the three goddesses and offering the apple to Venus. His soul is in fact located (and it’s a frightful thing to see) in his elbow’. (Kleist).[*Please, make sure that ‘[…]’ have been correctly situated in the quote] When Kleist says that the soul is located in the elbow, he is expressing the belief that the ‘inner’ soul, the ‘personality’ of the individual can be expressed through outward gestures. As Rudlin had said, one should not expect “psychological realism” in the Commedia dell’Arte, precisely because the psychology of this form of art is expressed solely through external, physical gestures. This is the first thing an actor has to learn when he dons a mask, the importance of physical gesture, as the mask has taken away his ability to employ anything else; even facial expressions have been factored out of this particular art form. Most facial expressions are merely a social mask, as Freddie had already observed, and so to truly express the self may paradoxically require something as impersonal as a mask, a point also made by Rudlin: “Masks live in the eye of the beholder, not of the actor. Mirror work is therefore prohibited since it leads to self18 STEPHEN BUTLER consciousness” (42). In Eclipse, Alex Cleave is an actor who has digested Kleist’s essay, and knows that natural grace is dimmed by thought, which is why for him the following vignette is a perfect example of his profession: I had never before witnessed such purity of gesture. All her actions — brushing her hair, pulling on her pants, fastening a clasp behind her back — had an economy that was beyond mere physical adroitness. This was a kind of art, at once primitive and highly developed. Nothing was wasted, not the life of a hand, the turn of a shoulder: nothing was for show. Without knowing, in perfect self-absorption she achieved at the start of each day in her mean room an apotheosis of grace and suavity. (101). The other figure from the Commedia Dell’Arte that Banville mentions as often as Pierrot and Colombine is Colombine’s actual lover, Arlecchino, since known as the Harlequin (Figure 6). What both he and Colombine have in common is physical grace. Colombine is often a ballerina dancer, and so possessed of physical adroitness, and the same is also true of the Harlequin. Rudlin describes him thus: “His paradox is that of having a dull mind in an agile body. Since, however, his body does not recognise the inadequacy of the mind which drives it, he is never short of a solution” (79). This is the antithesis of all the narrators that surface in Banville’s prose works. Alex refers to himself as the “thinking man’s thespian” who is good at playing ‘inner’ characters, which is why he is so fascinated by the “purity of gesture” of the woman that he observes, as it’s an apotheosis he is unable to realize himself. There is a case to be made that all of the narrators in Banville’s novels are the Pierrot type and so the Harlequin is always the rival figure precisely because he embodies everything that the narrators most desire for themselves. In Ghosts, Freddie won’t even discuss such a person, derived as he is from the Harlequin figure in Watteau’s painting Pierrot, located behind Pierrot on a donkey with a rather smug look on his face (Figure 7). Freddie discusses the Pierrot figure in this painting at great length, speculating on his origins and nature, but he is rather terse with the figure looming over Pierrot’s shoulder —“Of that smirking Harlequin mounted on the donkey’s back we shall not speak. No, we shall not speak” (216). Banville has no such qualms in his later novel Shroud, in which we have a long amalgamated quotation concerning the Harlequin figure culled from two sources: Pierre DuChartre’s The Italian Comedy, and Joseph deMaistre’s St. Petersburg Dialogues. Here, there is an inkling of the attraction of this figure for Banville: “He is the creator of a new form of poetry, accentuated by gestures, punctuated by somersaults, enriched with philosophical reflections and incongruous sounds. He is the first poet of acrobatics and unseemly sounds (italics mine)” (Banville, Shroud, 180). It is his physical grace that is the source of the 19 BANVILLE’S IRISH COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE attraction, as it was for Alex with the women he spied on, his acrobatics and gestures, which Axel describes as a form of poetry. Figure 6. Maurice Sand: “The Harlequin” Figure 7. Jean-Antoine Watteau: “Pierrot” When Diderot discussed the gestural nature of the actor’s art, he claimed that the artist had to divest himself of any emotional empathy with the role. Much of the criticism of Banville, even when positive, is that he often sacrifices feeling for his technical abilities as a novelist. In reviewing The Sea for The New York Times Book Review, Michiko Kakutani scornfully commented that Banville is “a highly cerebral author who emphasizes style over story, linguistic pyrotechnics over felt emotion”. The implication here is that linguistic skill and felt emotion are diametrically opposed qualities in fiction, but Banville actually explores the paradoxical nature of the relation between the two. McMinn comments on how the most unsettling aspect of Athena is that it is, to all intents and purposes, a “stylization of cruelty” (133). McMinn sees this cruelty as emanating from the perverse, fetishistic relationship between the two lovers in the novel, implying therefore that excessive stylization does induce emotion, only it is a perverse one connected with the deindividuation of the fetishist. In The Untouchable, however, Banville directly addresses the connection between stylization and felt emotion, by focusing on the artist Poussin as seen through the eyes of the main character Victor Maskell. Poussin, as artist, is often accused of the same defects as the novelist Banville, even by those critics who admire him. Anthony Blunt, who is the template for Banville’s character of Maskell, dedicated an entire study to Poussin, but even 20 STEPHEN BUTLER he occasionally comments on the lack of emotion in the artist: “This unusual method explains many of the features of Poussin’s style: its classicism, its marblelike detachment, and also its coldness, which at some moments comes near to lack of life” (193). The unusual method he’s discussing here again involves dolls and manikins, which Poussin would use to construct a three-dimensional model of the scene he was going to paint, so that he could get the perspective and the lighting just right. Delacroix believed that such a method resulted in a certain “dryness” in Poussin’s paintings, which Blunt would certainly have taken to be an emotional dryness. As is the case with the Commedia dell’Arte, Poussin’s paintings involve classical types and poses which leave in the eye of many a critic a cold feeling, even in Blunt.1 The paradox though, is that Poussin used these formal techniques precisely to invoke an emotional response in his audience. Maskell notices Poussin’s “stylized, gorgeous cruelty” in certain paintings (Figure 8), and Banville provides a direct quote from Blunt’s study of Poussin to show that this paradoxical relationship between style and feeling is a key concern of Poussin’s: “The problem for Poussin in the depiction of suffering is how to stylize it, as the rules of classical art demand, while yet making it immediately felt” (234). Figure 8. Nicolas Poussin: “Et in Arcadia Ego” 1 McMinn sees something similar in Banville’s novel, as he describes Victor Maskell as Banville’s “coldest” narrator to date. 21 BANVILLE’S IRISH COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE Poussin himself tried to solve this particular dilemma by plagiarizing the musical theory of Gioseffe Zarlino and introducing his theory of modes. He related this theory to his patron, who had accused him of producing paintings lacking any felt emotion. On the contrary, argued Poussin, his paintings do possess an emotional resonance, due to their use of several modes, derived from the Greeks, and which are selectively assembled in the painting: “particularly when all the things which entered into the composition were put together in such proportions that there arose the capacity and power to arouse the soul of the beholders to diverse emotions” (Freeberg, 77). What is important is not the emotion of the subject of the painting, but rather how it is composed; with “proportion” and “measure” as the primary means to excite emotions in the eye of the beholder. These characteristics can only be appreciated by a mind fully engaged with the painting, for as Poussin firmly believed: “Our sense alone ought not to be the judge, but reason too” (Freeberg, 80). Kakutani uses the word “cerebral” in an almost sneering tone which would have been looked on unfavourably by Poussin. He believed, as does Maskell in The Untouchable, that “pictures were more a matter of mind over eye” (Banville, 4). Emotions are not to be “expressed” in the paintings, but rather “excited”, a distinction drawn attention to by David Freedman when discussing the emotional impact of Poussin’s work. They are “excited” by the use of proportion, which actually produces an effect in the mind of the spectator, similar to the effect that rhythmical proportion does in music. Poussin believed that in both music and painting there is a “certain determinate order, [which] has a closure to it by which the thing conserves its being” (Freeberg, 82). It is the order of a work of art that produces its emotional effects, not its subject, which was something that Freddie also comments on in his long disquisition on Watteau’s Pierrot painting. He employs the same musical terminology as Poussin: “a subtle harmonics is at work here, which plays upon our expectations of symmetry and balance […] it is first of all a masterpiece of pure composition, of the architectonic arrangement of light and shade, of earth and sky, of presence and absence” (Ghosts, 87). Freddie is also using the same terminology as David Freeberg, who believes that in his theory of modes Poussin was trying to describe an aesthetic process referred to by Kant as “the architectonics […] of mental operations”. Freeberg believed that Poussin was trying to describe the “innate levels of response” in observing pictures, and was providing a “syntax of correlations between pictures and responses” (81). This paper has come full circle, as it was precisely this aspect of the Commedia dell’Arte and its use of the mask that Banville was most interested in. To reiterate Rudlin’s thesis: “In the liminal phases of life such as Carnival and Fiesta, persona, because it is of all times and all places, readily 22 STEPHEN BUTLER overcomes personality, which is time and place specific”. Persona is a syntactical quality, free of the semantics and semiotics of time and place. The emotional effects of the mask in theatre, of gesture on the stage, modes in music, or compositional techniques in painting, are “innate”, they are biologically rather than socially conditioned, and no matter how technical they may be, they do induce an emotional response. W.B. Yeats was a fellow Irish writer who knew this truth in his famous poem “Among School Children” when he wrote: “Both nuns and mothers worship images […] [that]keep a marble or a bronze repose./And yet they too break hearts” (244). The emotional response to the image, or the gesture, is often connected with its status as image, a point made by the art critic John Berger: The most important thing about paintings themselves is that they are images, are silent, still […] the experience of this has nothing to do with what anybody teaches about art. It’s as if the painting, absolutely still, soundless, becomes a corridor, connecting the moment it represents with the moment at which you are looking at it. And something travels down that corridor, at a speed greater than light, throwing into question our way of measuring time itself. (4). The same is true of the Commedia dell’Arte, which telescopes time in a different fashion: “The mask enables the spectator to see not only the actual Arlecchino before him, but all the Arlecchinos who live in his memory” (Rudlin, 36). By subverting time in this fashion art of any fashion is able to help mankind escape its seemingly inescapable clutches, offering something that all Banville’s narrators long for: redemption.2 Despite his perverted and murderous nature, or possibly even because of it, Freddie perfectly encapsulates what he sees as the redemptive force of art through his love of both A and his paintings: “the witness that she offers is the possibility of transcendence, both of the self and of the world, though self and world remain the same” (Athena, 208). References Banville, John. The Untouchable. London: Picador, 1997. Print. Banville, John. Athena. London: Picador, 1998. Print. Banville, John. The Book of Evidence. London: Picador, 1998. Print. 2 Fellow Irish writer Derek Mahon expresses a similar yearning in his The Yellow Book: “[an] uninterruptible dream/of art as redemptive form”. 23 BANVILLE’S IRISH COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE Banville, John. Ghosts. London: Picador, 1998. Print. Banville, John. Eclipse. London: Picador, 2000. Print. Banville, John. Shroud. London: Picador, 2002. Print. Banville, John. The Sea. London: Picador, 2005. Print. Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: BBC and Penguin Books, 1972. Print. Blunt, Anthony. Art and Architecture in France, 1500 to 1700. London: Penguin Books, 1953. Print. Diderot, Denis. The Paradox of Acting. Translated by William Archer. New York: Hill and Wang, 1957. Print. Freeberg, David. “Composition and Emotion”. The Artful Mind: Cognitive Science and the Riddle of Human Creativity. Ed. Mark Turner. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. Print. Kakutani, Michiko. “A Wordy Widower with a Past”. New York Times Book Review (2005). Web. 24 Apr. 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/11/01/books/ 01kaku.html. Kenny, John. “Well Seen, Well Said: the Pictorial Paradigm in John Banville’s fiction”. Irish University Review 361 (2006): 52-67. Print. Kleist, Heinrich von. “On the Marionette Theatre”. Trans. Idris Parry. Web. 24 Apr. 2010. http://southerncrossreview.org/9/kleist.htm Longley, Edna. The Living Stream: Literature and Revisionism in Ireland. Newcastle: Bloodaxe Books: 1994. Print. McGrath, Patrick. “An elegiac love letter”. The Irish Times (11.02.1995): 24. Print. McMinn, Joseph. The Supreme Fictions of John Banville. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999. Print. Nietzsche, Friedrich. Beyond Good and Evil. Translated by R.J. Hollingdale. London: Penguin, 1973. Print. O’Toole, Fintan. “The Clank of Irish Bones”. Prospect Issue 111 (2005): 17. Print. Rudlin, John. Commedia Dell’Arte: An Actor’s Handbook. London: Routledge, 1994. Print. Speight, Allen. Hegel, Literature, and the Problem of Agency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Print. 24 STEPHEN BUTLER Tseëlon, Efrat (ed.). Masquerade and Identities: Essays on Gender, Sexuality, and Marginality. New York: Routledge, 2000. Print. Yeats, William Butler. Collected Poems. London: Picador, 1990. Print. 25