Charles Turner Thackrah on the Health of Factory Workers, 1832

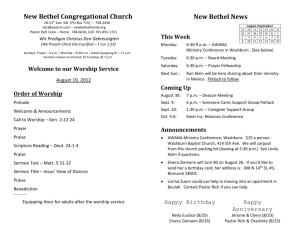

advertisement

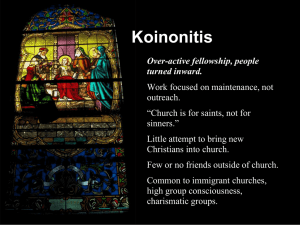

Dr. John Allen on the mining population in Northumberland and Durham in 1840 Report to the Committee of Council for Education, Parliamentary Papers, 1841, XX, pp. 159-161; in G. M. Young and W. D. Hancock, eds., English Historical Documents, XII(1), 1833-1874 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956), pp.968-69. John Allen describes the lives of the miners in the North and appeals to the paternalistic instincts of the middle and upper classes to minister to the spiritual and educational needs of the workers.) . . .As far as regards their outward circumstances, perhaps few classes among our labouring population are in a better condition than the colliers of the northern district. After working for eight or ten hours in the pit, they come home to wash themselves thoroughly, and sit down to a plentiful meal. Their houses are in general clean, roomy, and well furnished. You can scarcely enter one which does not contain a good four-post bedstead, a mahogany chest of drawers, and a clock. Each householder fives rent-free, paying only 3d per week for the leading of his coal. A small plot of ground for potatoes is commonly attached to each dwelling; and large families, if provident, make a bargain with their employers for grass for a cow.... The pitmen have hitherto been little influenced by political agitations. Reading rooms do not prosper among them; and although some sale for worthless and seditious papers is doubtless found amongst them, the publications chiefly circulated are books of piety and devotion. In one cottage I noticed Adam Clarke's Bible, Wesley's Sermons, Milner's Church History, and Leighton's Works. Those who have any deep religious feelings are ordinarily Methodists. The parishes are extensive, and the great tithes are not often in the hands of the incumbents. On the winning of a colliery, a large population is suddenly located in a district which may very probably be some miles distant from the church, the pastor of which may find his charge increased within a few months by some thousands, the families being sometimes brought into the parish by carts, to the number of 500 in a day. The church is almost unavoidably slow in her operations; it requires considerable exertion to raise a consecrated place for worship within three years; but in this time the people must in a great measure have formed their habits, and such as are disposed to listen to teachers will have found them for themselves. An instance was pointed out to me where, in a few weeks, a population Of 3000 had risen up at the distance of three miles from the parish church, the incumbent having to provide additional spiritual attendance and the means of locomotion, out of an income of £75 per annum. A person well acquainted with the district, mentioned 6000 or 7000 as the average number of persons which, in the thickly populated parishes, fell to the charge of a single clergyman-a disproportion which is greatly increased when we take into account that, out of every 100 clergymen, probably 20 at least, from some cause or other, will not be effective among a population so difficult of access. Within the last 16 years the attention of the clergy has been visibly drawn to the necessity for raising school-houses and unconsecrated buildings for public worship contemporaneously with the introduction of this shifting population into remote neighbourhoods. The owners of collieries are, in most cases, willing to provide their labourers with a room which may be used as a day and night-school during the week, and on the Sunday is opened to one or two sects (and in some instances three) in succession, for the purposes of public worship. But in very few cases does it seem to have occurred to those who derive such large revenues from the soil, that, for a man to be in any sense the spiritual pastor of the people, he must be with them as their adviser and friend during the week as well as a preacher to them on the Sunday.... In the present state of things Sunday-schools are an institution to which the serious minded will look with the deepest interest. It is true that the instruction given at such schools must be very limited, and the teachers are often very little fitted, by their age and their habits of thought, to dig into the minds of others. In many places pious poor may be found, but what these have, they commonly are not able (through deficiency of training) to impart to others. But may we not hope that persons of a higher range of understanding, of more thought, information, and experience, will gradually be induced to give their services to the amelioration of the condition of those beneath them? Are not the upper classes becoming daily more sensible of their identity of interest with those whose faculties of labour are their sole inheritance? Are there no signs of a growing sense of the responsibilities men are laid under by superior rank and education? The great want felt through the whole district is that of schoolmasters, men who may be better educated and more systematically trained, but above all, men who may in some degree be sensible of the great trust reposed in them when a parent confides to them the education of his children.