Individual Winner, Jonathan Liebman, 11th Grade, Champlain

advertisement

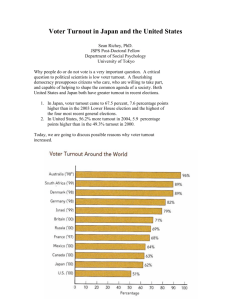

Jonathan Liebman March 18, 2012 Voting in the United States: A Troubling Quandary At the close of the Constitutional Convention of 1789, a woman approached Benjamin Franklin and inquired as to what form of government the Framers had decided upon. Franklin famously replied, “A republic, if you can keep it”, thereby entrusting the fate of the country to the general populace and endowing the rights of self-government and voting to “we the people”. Two centuries later, it is evident that America’s so-called “great experiment with democracy” has been—by almost any measure—a resounding success. The United States has developed into the world’s most enduring republic; an economic and political engine championing the values of freedom and democracy. Yet the defining feature of democracy is its reliance on the citizens to ultimately make decisions; a system by which political power is obtained with the just consent and input of the governed. As such, preserving and strengthening the right to vote is imperative for a robust democracy, for a country in which the citizens do not vote cannot rightfully be called democratic. And if a democracy is to be judged by its voter participation, the United States isn’t quite a paragon of virtue, nor has it ever been. Indeed, the road to greater political equality has been slow and fraught with division. The right to vote—initially afforded only to a tiny elite— has been gradually expanded to include people who don’t own property, African-Americans, women, and younger adults over the age of 18. Even today, voter turnout in the United States remains worryingly low, especially in comparison to other Western democracies. Since the 1960s, turnout in Presidential elections has averaged around only 55% of eligible voters (Patterson)—a marked difference from other democracies such as France, Belgium, and Germany, which routinely boast voter turnout rates of 80% or above (Ibid). Among young voters, the situation is even worse: in the 2010 midterm elections, only about 20% of eligible voters under the age of 30 went to the polls, while voter turnout overall was at around 41%. There are a myriad of reasons which help explain why this unfortunate situation is so. Firstly, voting in the United States is neither particularly easy nor encouraged. Unlike other countries which automatically register voters, the US puts the onus on citizens to enroll themselves, at locations and during time periods that aren’t particularly publicized. Moreover, some states are now employing measures such as Voter ID laws that serve to depress voter turnout, particularly among minorities (Cohen). In short, burdensome voting requirements and procedures inhibit voter turnout. Voter turnout is also low due to voter apathy or alienation. Distaste for politics is widespread among the public—I myself have witnessed numerous times people professing their hatred for everything political. Others simply display no interest whatsoever to politics, believing that voting is simply an exercise in futility; a quixotic quest for change that inevitably will fail. Given the ugly gridlock and the virulent negativity that mark American politics today, the reasons people develop such views are understandable. However, such beliefs both hurt our democracy and act as self-fulfilling prophecies: politics reward those who vote and participate, and by voluntarily shutting oneself out of the process, one precludes the possibility of benefiting. Although these problems facing our democracy are ample, there are remedies available which would serve to heighten voter turnout. Changing to an automatic registration system more in line with other Western democracies would ease the burden on people increase voter turnout, as would repealing the voter ID laws that effectively disenfranchise a significant portion of voters. Making Election Day a national holiday (or more unlikely, shifting it to a weekend) would also be a helpful measure—by doing so, Americans would no longer be forced to vote on a busy workday, but would instead be given a holiday to do so. Apart from logistical remedies to onerous voting challenges, there are societal and educational ways to increase voter turnout. Although political ads and news floods the airways, we don’t live in a particularly civic-minded society. Many don’t care about politics because they never properly learned about it, lacking a true understanding of how the political world works. In the same vein, many people are apathetic because they fail to understand politics actual relevance to their lives. Increasing education politics would thus serve to increase voter turnout by encouraging an interest in politics—indeed, studies have shown a consistent and highly significant relationship between educational attainment and voting rate (Patterson). Moreover, by taking steps such as increasing education and consecrating Election Day as a national holiday, a more politically active and civic-minded culture would develop. In doing so, apathy would be combated and voter turnout would thus rise. Although there are a number of ways voter turnout can be improved, there already are a number of resources available to me and to other students my age to aid us in the registration and voting process. So-called “motor-voter” laws allow adults of all ages to register to vote at the DMV when conducting other business, which is an easy, painless, and efficient way to get registered. Absentee ballots are available for college students and people who will be out of town, and early voting is a possibility for people who may be busy on Election Day proper. Registration can be also completed and done at the town clerk’s office, making registration also fairly easy, and it can even be mailed in. Lastly, organizations like Rock The Vote exist specifically to help register and encourage the young to vote, and are available for assistance should any help be required. Upon examining the history of the United States, there is a sense of accomplishment at how far as a country we have come. Our path to political equality has been arduous but successful, and it is a journey worthy of recognition. Yet it is also a journey that is still incomplete; one which we must not grow complacent about. By improving voter turnout, we can continue to take this road further; improving the robustness of our republic and the vitality of our democracy. Bibliography Cohen, Andrew. "How Voter ID Laws Are Being Used to Disenfranchise Minorities and the Poor." The Atlantic. 16 Mar. 2012. Web. 18 Mar. 2012. <http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2012/03/how-voter-id-laws-are-beingused-to-disenfranchise-minorities-and-the-poor/254572/>. Patterson, Thomas E. The American Democracy. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990. Print.