2 Syllable and word structure

advertisement

The phonology of Cicipu

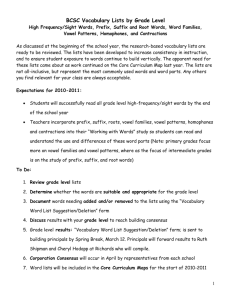

Table of Contents

1Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 2

2Syllable and word structure................................................................................................................ 2

2.1Unambivalent syllables .............................................................................................................. 2

2.2Labialisation and palatalisation .................................................................................................. 6

2.3Long consonants ......................................................................................................................... 7

2.4Long vowels and diphthongs...................................................................................................... 8

2.5Prenasalised stops and affricates .............................................................................................. 10

2.6Approximants ........................................................................................................................... 16

2.7Other word classes ................................................................................................................... 16

2.8Word structure .......................................................................................................................... 18

2.9Summary .................................................................................................................................. 19

3Consonants ....................................................................................................................................... 20

3.1Phonemic inventory.................................................................................................................. 20

3.2Allophones and general phonetic rules .................................................................................... 20

3.3Distribution in noun and verb roots.......................................................................................... 22

3.4Length ....................................................................................................................................... 26

3.5Cross-linguistic comparisons ................................................................................................... 32

4Vowels ............................................................................................................................................. 33

4.1Phonemic inventory.................................................................................................................. 33

4.2Allophones and general phonetic rules .................................................................................... 34

4.3Nasal vowels ............................................................................................................................ 37

4.4Long vowels and diphthongs.................................................................................................... 37

4.5Distribution............................................................................................................................... 42

5Tone ................................................................................................................................................. 42

5.1Tone inventory ......................................................................................................................... 42

5.2Downdrift, downstep, and upstep ............................................................................................. 43

5.3Depressor consonants ............................................................................................................... 45

5.4Spreading .................................................................................................................................. 46

5.5Polar tone.................................................................................................................................. 50

5.6Lexical tone in nouns ............................................................................................................... 51

5.7Grammatical tone ..................................................................................................................... 52

6Vowel harmony ................................................................................................................................ 61

6.1Distribution of vowels in CVCV noun roots ............................................................................ 61

6.2Affixes ...................................................................................................................................... 61

6.3Compounds and larger domains ............................................................................................... 65

6.4Loanwords ................................................................................................................................ 66

6.5Cross-linguistic comparisons ................................................................................................... 66

7Nasalisation ...................................................................................................................................... 66

7.1Phonemes affected.................................................................................................................... 67

7.2Direction ................................................................................................................................... 67

7.3Domain ..................................................................................................................................... 68

8Morphophonemic processes ............................................................................................................. 68

8.1Coalescence and elision ........................................................................................................... 68

8.2Homorganic nasals ................................................................................................................... 71

8.3u-anticipation ............................................................................................................................ 72

8.4i-anticipation............................................................................................................................. 73

8.5Vowel/approximant interaction ................................................................................................ 74

1

Introduction1

This paper provides a phonological sketch of the Cicipu language of north-west Nigeria. Cicipu is

part of the West Kainji subgroup of Benue-Congo, and is spoken by approximately 20,000 people

in Niger and Kebbi States. Almost everyone is bilingual in the lingua franca Hausa, and many speak

a further West Kainji language. The analysis in this paper is based on two field trips to the Cicipu

area made by the author; from September 2006 until March 2007, and from January-April 2008.

During that time I made recordings of approximately fifteen hundred words as well as several hours

of text, six hours of which has been transcribed and annotated. My analysis here is based on this

data, together with elicitation sessions with Musa Ɗanjuma mai Unguwa, Markus Mallam Yabani,

and Ibrahim Ɗanjuma mai Unguwa. They are all speakers of the Tirisino dialect of Cicipu, from

which all the data in this paper is taken. The other six dialects are very similar with respect to

lexico-statistical counts (> 95%), but no serious phonological analysis has been carried out for any

of them. This fact should be taken into account in any orthographic decisions.

The paper starts with an analysis of syllable and word structure in Cicipu (§2), which then informs

the discussion on consonants (§3) and vowels (§4). The next three sections deal with three

important suprasegmental topics in Cicipu: tone (§5), vowel harmony (§6), and nasalisation (§7).

Finally (§8) I discuss some of the more important morphophonemic processes in Cicipu. Sections 5

and in particular 7 and 8 are by no means complete – they are intended to provide a point of

departure for more detailed research in the future, rather than a polished presentation.

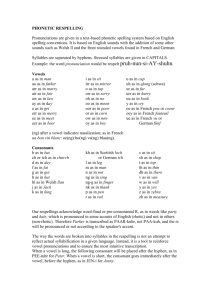

Cicipu examples are given in a phonemic transcription, unless enclosed in [square brackets] in

which case an IPA phonetic transcription is used. In the phonemic transcription /y/ stands for the

palatal approximant [j], /c/ and /j/ for the affricates [tʃ] and [dʒ] respectively, the apostrophe /'/

represents the glottal stop [ʔ]. A double vowel /aa/ indicates a long vowel [aː]. Tone and nasality

are marked on the first vowel only (/a ̃́a/) but apply to both vowels ([a ̃́ː]) – in the case of a

contour tone this is usually realised over both vowels together. Phonetic transcriptions are varyingly

broad or narrow depending on the distinctions in question in the relevant section.

2

Syllable and word structure

I will first consider the unambivalent syllable structures found in noun and verb roots (§2.1), before

turning to the more complex ambivalent cases (§2.2-§2.6). Section 2.7 deals with prefixes and

ideophones, which allow extra syllable types, and in §2.8 I will look at the overall structure of

nominal and verbal roots, in terms of their constituent syllables.

2.1 Unambivalent syllables

The only unambivalent syllable structure found in Cicipu noun and verb roots is CV, although as

we will see there is a convincing case for analysing some roots as beginning with a V syllable, as

well as a fairly strong one for admitting CVN2 word-initially. Firstly, here are some examples of

CV syllables in noun roots:

1 Thanks to Roger Blench, David Crozier, Steve Dettweiler, David Heath, James MacDonell, Heidi Rosendall, Becky

Smith, and Israel Wade for their help with certain parts of the analyses here, and for sharing their data on other West

Kainji languages.

2 Standard abbreviations are used when referring to syllable typesː C(onsonant), V(owel), and N(asal) consonant.

(1)

kà-kúlù

à-kúlù

NC1-hailstone

NC2-hailstone

hailstone

hailstones

[eamy003.1337]3

(2)

kù-dávù

à-dávù

NC9-mortar

NC2-mortar

mortar

mortars

[eamd002.083]

(3)

s-síró

ì-síró

NC8-mane

NC3-mane

mane

manes

[eamd020.1033]

The following examples show CV syllables in verb roots:

(4)

ù-páɗà

u-paɗa-LHL4

3S-slaughter-RLS

he slaughtered

[eamy031.097]

(5)

ù-sítà

u-sita-LHL

3S-swell-RLS

it swelled

[eamd013.213]

3 Abbreviations used in this paper are 1 = first-person, 2 = second-person, 3 = third-person, ART = article, CAUS =

causative, CMPL = complement case, AG = agreement, APPL = applicative, COP = copula, DIR = directional, FUT =

future, GEN = genitive, HAB = habitual, IMP = imperative, IRR = irrealis, ITER = iterative, LOC = locative, LW =

loanword, NC = noun class, NEG = negative, NMLZ = nominaliser, P = plural, PASS = passive, PFV = perfective, POSS =

possessive, PRO = pronoun, REDUP = reduplicated, RES = resultative, RLS = realis, S = singular. The Leipzig glossing

rules are followed where possible.

4 Verbs in Cicipu are inherently toneless. The three moods (realis, irrealis, and imperative) are encoded by different

tone patterns superimposed on the verbs, and are distinguished in the glosses where relevant.

(6)

ù-náhà

u-naha-LHL

3S-leave-RLS

he left

[eamd006.022]

The identification of vowel-initial syllables is less straightforward, since they do not always appear

as such on the surface. A number of roots, however, can be set apart from the rest because of their

unusual behaviour. Consider the forms in (7-9) (nouns) and (10-12) (verbs), given in a broad

phonetic transcription:

(7)

kóosì

óosì

NC1ːeye

NC2ːeye

eye

eyes

[eamd004.022]

(8)

kwéetú

éetú

NC9ːmedicine

NC2ːmedicine

medicine

medicines

[eamd013.209]

(9)

vɔ́ɔmɔ̀

yɔ́ɔmɔ̀

NC8ːmonkey

NC3ːmonkey

monkey

monkeys

[eamd020.1001]

(10)

mǔuwà

NC4:hear:RLS

it heard

[eate002.001.054]

(11)

mǎayà

AG5:come:RLS

they came

[saff001.002]

(12)

wǔutò

3S:go_out:RLS

he went out

[eaim003.1408]

The nouns in (7-9) and the verbs in (10-12) differ from their counterparts in (1-3) and (4-6) in two

ways. First, they take a different set of nominal and verbal prefixes. While most nouns behave like

-kúlú 'hailstone' and -dávù 'mortar' which take a CV-shape prefix in the singular, the second type

of nouns appear at first sight to have a C-shape prefix, as suggested by the pair vɔ́ɔmɔ̀ 'monkey'

and its plural yɔ́ɔmɔ̀. A better way of looking at this is that the prefix remains CV-, but that its

vowel has coalesced with the first root vowel, resulting in a long vowel with the same quality as the

root vowel. This process can be represented as follows using standard autosegmental notation:

Figure 1: Autosegmental representation of examples (7) and

(10)

x x

x x x

k a - o s

L

H

i

L

x x

x x x

ma - u w a

L

H

L

The first diagram shows what happens when a noun class prefix is attached to a vowel-initial root.

The prefix vowel is de-linked from the timing tier, and the [o] vowel quality spreads to the empty

slot. Thus the number of timing slots (and hence morae) is preserved, but the prefix tone is lost. The

second diagram represents a subject agreement prefix plus vowel-initial verb root, and differs

slightly from the first. Although the number of weight units still remains the same, this time the

tone of the prefix is not lost, but spreads to the /u/ vowel. This vowel is therefore now attached to

two tones, LH, and this is realised phonetically as a rising tone.

Vowel-initial roots in Cicipu are rare (49 out of 950 nouns, 10 out of 471 verbs), and may well be

derived from consonant-initial roots, especially those beginning with an approximant. For example,

the vowel-initial verb uto 'go out' is pronounced wuto by some speakers. The only example of the

latter in the corpus was spoken by a grandmother in response to her grandson, who had used the

vowel-initial form in the previous utterance. The Tirisino word for 'eye', kóosì, may be in the

process of undergoing this change. The plural in Tirisino is òwósì, and in the Tikula dialect the

singular is kò-wósì. This suggests that the Tirisino word may be changing from a w-initial root to a

o-initial root, with the plural retaining the older form.

The second difference between consonant- and vowel-initial roots involves the selection of the

prefix consonant. Certain noun classes prefixes (and also some person agreement prefixes) surface

with a different consonant depending on whether the first phoneme of the root is a vowel or a

consonant. Compare first the words in (3) with those in (9); in the former example, with a

consonant-initial verb, the plural NC3 prefix is i-, while in the latter example, with a vowel-initial

verb, the plural NC3 prefix is y-. While this variant can be considered a phonotactically-conditioned

allomorph of an underlying /i/ prefix, the same cannot be said for the NC8 singular prefixes found

in the same examples. The consonant-initial root -síró 'mane' in (3) occurs with a consonantlengthening prefix C- (see §4 for details), whereas the vowel-initial root -ɔ́mɔ̀ 'monkey' has a prefix

beginning with the v-. The same situation obtains for the person prefixes on verbs. Considering the

verbs in (6) and (12); in the first example the consonant-initial verb takes an u- 3S prefix, in the

second the vowel-initial verb takes a w- 3S prefix, similar to the i-/y- alternation just discussed.

However for the 1S, 2S, and 3P person prefixes shown in tables 1 and 2 below, the two variants are

less predictable and have to be independently-specified – providing further motivation for the

separation of consonant- and vowel- initial roots. In these tables, and in the rest of the paper, the

symbol A represents an underspecified vowel which harmonises with the root to which it is attached

(see §6 for details). V represents a vowel which assimilates totally with the following vowel, and

likewise C represents an underspecified consonantal weight unit, which assimilates completely to

the consonant to which it is attached. N represents a nasal homorganic with the following

consonants. Note that these abbreviations are not at the same level of phonological representation as

those used when discussing syllable types (see footnote 2) – here we are dealing with individual

morphemes, not syllables.

NC1

NC2

NC3

NC4

NC5

NC6

NC7

NC8

NC9

C-initial kA-

A-

i-

mA-

N-/mi-

ti-

u-

C-/Ø-

ku-

V-initial kV-

V-

yV-

mV-

mV-

tV-

wV-

vV-

kʷV-

Table 1: Consonant-initial and vowel-initial noun class prefixes

1S

2S

3S

1P

2P

3P

C-initial N-

C-/Ø-

u-

ti-

i-

A-

V-initial mV-

vV-

wV-

tV-

yV-

hV-

Table 2: Consonant-initial and vowel-initial person agreement prefixes

Borrowed words with CVC syllables in the source language (invariably this is Hausa) are

pronounced with a transitional schwa vowel, since CVC syllables are generally unacceptable in

Cicipu.

(13)

[kà-húsᵊ kà]

NC1-face

face [Hausa fuska]

[eamd004.020]

(14)

[ʔàlᵊ máːdʒìɾíː

]

beggar

beggar [Hausa almajiri]

[eamd016.405]

Words such as 'àlmáajìríi 'beggar' which begin (phonetically) with a glottal stop are considered

to be underlyingly vowel-initial in many languages, the glottal stop being inserted to prevent a

vowel-initial syllable. However in Cicipu, words beginning with a glottal stop should not be

considered vowel-initial, as can be seen from the plural form of (14), ì-'àlᵊ máajìríi 'beggars'5.

5 The glottal stop in Cicipu is not always phonemic however. See §8.1 for further discussion.

In summary, the two types of root illustrated in (1-6) and (7-12) show differences in prefix

consonant, vowel-length, and tone, and the simplest way to account for this is to assume that the

second type of root is vowel-initial. Therefore in underlying representations we have V syllables as

well as CV, but the former are never realised phonetically.

2.2 Labialisation and palatalisation

In the last section I gave examples of words containing V and CV, and stated that these are the only

unambivalent syllable types. Not surprisingly, there are also words in Cicipu where the syllable

types are less easy to discern. This subsection and the next four will consider five different

complications. First of all, a number of consonants can be labialised or palatalisedː

(15)

[ù-kʷáɾí

mɔ̀-ʔʲ ɔ́ʔʲ ɔ́

ù-ʔʷ âː

ù-hʲa ̃̂ː]

ù-kwárí

mɔ̀-'yɔ́'yɔ́

ù-'wâa

ù-hya ̃̂a

NC7-next_year

NC4-fish

3S-pass\RLS

3S-say\RLS

next year

fish

he passed

he said

These sequences (kʷ, ʔʲ etc...) could be interpreted either as single consonant phonemes, as two

separate consonants, or as a consonant followed by a rising diphthong. There are no unambivalent

rising diphthongs in Cicipu, nor any unambivalent consonant clusters, so in the absence of any

further evidence from patterning in phonological processes, economy of description would dictate

that these should be considered as single consonant phonemes. However there is also positive

evidence that that these should be considered single phonemes, coming from the allomorphs of the

conjunction /ǹ/ 'and'. Before short consonants we find the [ǹ] allomorph, while before long

consonants we find [nì], since NCː clusters are not allowed in Cicipu. The relevance for this

discussion is that words beginning with labialised consonants pattern with the words beginning with

short consonants, as shown by [ìn kʷánda ̃́i] 'with the dry season'.

In contrast to other West Kainji languages such as Pongu (MacDonnell 2007) or Duka (Heath and

Heath 2002) where almost every phoneme has labialised or palatalised versions, there are only six

such consonants in Cicipu (kʷ gʷ ʔʷ ʔʸ hʷ and hʸ ), and therefore the decision to treat

them as phonemes does not greatly increase the Cicipu phoneme inventory. As a result of this

analysis the roots in (15) are assumed to consist of CV rather than CCV syllables.

2.3 Long consonants

Long consonants occur word-initially in nouns of class 8, and word-medially in a few verbs. They

are perhaps best considered to be single segments phonetically, but to be ambisyllabic

phonologically. Ladefoged and Maddieson (1996ː 92) point out that a phonological distinction can

be drawn between geminates and a sequence of two-identical stops, such as may occur across a

morpheme boundary. In Cicipu, it seems that long consonants are true geminates. They never have

an intervening epenthetic vowel (unlike the borrowed words in (13-14)), and when complex

segments such as affricates are lengthened the resulting sound consists of a single long closure

followed by a single frication period, rather than a simple repetition of the short version. Both these

facts suggest that long consonants should be treated as a single phonetic segment. Nevertheless in

weight-sensitive phonological phenomena long consonants pattern with other 'heavy' sequences

such as long vowels. For example, the tone pattern on CVCV verbs in the habitual is L L H H, but

for CVVCV and CVNCV verbs the pattern is L L HL L. Verbs with a long C26 consonant pattern

with the other 'heavy' words, as shown in the examples below:

(16)

ù-sì-tá'á

3S-HAB-want

He wants

(17)

ù-sì-pɔ́ǹtɔ̀

3S-HAB-clap

He claps

(18)

ù-sì-wîinà

3S-HAB-sell

He sells

(19)

ù-sì-câa

3S-HAB-give

He gives

(20)

ù-sì-hɔ́ttɔ̀

3S-HAB-warm_oneself_by_fire

He warms himself by the fire

Phonetically, when there is a long consonant in C2 it closes off the previous syllable, so that V1 is

shorter than it would be in an open syllable. Therefore a word such as hɔttɔ in (20) should be

analysed as CVC.CV rather than CVCV. Thus it seems we have to admit the syllable pattern CVC

as well as CV, at least for syllables which end in a long consonant.

2.4 Long vowels and diphthongs

A sequence of a consonant followed by a long vowel can be analysed either as CVː or as CV.V. In

the latter case there are two syllables.

Historically it seems likely that long vowels in Cicipu are derived from the coalescence of two

syllables with the disappearance of the intermediate consonant, as with the emergence of vowelinitial roots (§2.1). Many of the long vowels in Cicipu have cognates in other languages where this

consonant remains, and there is also evidence from amongst the different Cicipu dialects. The

following tables show some of the relevant examples.

6

V1 = first vowel of the root, V2 = second vowel of the root, C1 = first consonant of the root, and so on.

Tirisino form

Gloss

Cognates

hyãa

say

hyã'ã (Tikula7)

tâa

food

tá'à (Tikula)

kɔ̀-kɔ̃̂ ɔ

n-náa

egg

cow

kɔ̀-kɔ̃́ 'ɔ̀ (Tizoriyo, plural ɔ̀-kɔ̃̂ ɔ), ko-kowo (Western Kambari)

ka-naka (Western Kambari)

koo

die

kuwə (Central and Western Kambari)

sɔɔ

drink

sɔwɔ (Central Kambari and Tsuvaɗi), so'o (Western Kambari)

raa

eat

lya'a (Western Kambari)

ì-ɗáa

ground

i-ɗaha (Tsuvaɗi)

zɔɔsɔ

laugh

zɔ'ɔsɔ (Central Kambari)

Table 3: Roots containing long vowels in Tirisino and their cognates in other Kambari cluster varieties

Tirisino form

Gloss

Cognates

c-cɔ́'ɔ̀

sheep

c-cɔɔ (Tikula)

ta'a

want

taa (Tikula)

kè-ré'è

tongue

kè-rêe (Tikula)

rì-hya ̃́'a ̃̀ arrow

ri-hyaa (Ticihun)

mò-hi ̃́'i ̃̀ blood

mə-hii (Ticihun)

tóríhi ̃̀

tə̃́ːlí (Central Kambari)

six

Table 4: Roots containing long vowels in other dialects from the Kambari cluster and their cognates in Tirisino

Given this historical relationship, we might expect to find that long vowels pattern as two syllables

rather than one synchronically as well. Certainly long vowels are more prone than short vowels to

carry a contour tone, but this does not allow us to decide whether they are disyllabic, or

monosyllabic with two morae (i.e. heavy), as in example (17) with a prenasalised consonant. In fact

the habitual tone pattern discussed in the previous subsection provides relevant data. Examples (16),

(18), and (19) are repeated here for convenience:

(21)

ù-sì-tá'á

3S-HAB-want

He wants

(22)

ù-sì-wîinà

3S-HAB-sell

He sells

7 Data on Tirisino, Tikula, and Tizoriyo is from my own fieldwork. Data on Ticuhun is from Dettweiler and

Dettweiler (2002), Tsuvaɗi – Lovelace (n.d.), Western Kambari (Stark 2004), Central Kambari (Hoffman 1967 and

Crozier p.c.).

(23)

ù-sì-câa

3S-HAB-give

He gives

Recall that the habitual tone pattern is L L H H if the first syllable of the verb root is light as in (21),

and L L H L otherwise. The important point here is that a certain group of monosyllabic verb roots

such as caa behave as if they consist of one heavy syllable CVV rather than two light syllables

CV.V. Other monosyllabic verb roots with apparently long vowels pattern with CV.CV roots, as in

(24):

(24)

ù-sì-da ̃́a

3S-HAB-stretch

He stretches

There are two possible interpretations of (24) – either that dãa and other such verbs have

underlyingly short vowels and so the root is CV and therefore light, or that they consist of two light

syllables CV.V, and hence pattern with CV.CV. It would seem to do less violence to the facts to

analyse such verbs as CV.V, but the matter is complicated and will be taken up again in §4.4. For

the moment all we can say is that some roots with long vowels appear to be bimoraic monosyllables

(e.g. caa).

Diphthongs differ from long vowels (and other ambiguous CVV/CVyV/CVwV sequences) in that

their duration is not noticeably longer than short vowels, and there cannot be a 'dip' in the

waveform. When words are broken down into syllables by native speakers then the diphthong is

pronounced as part of one syllable. Therefore diphthongs are considered to be a single vowel with

regard to syllable structure (see §4.4 for further detail).

2.5 Prenasalised stops and affricates

In addition to unambivalent CV consonants, it is common to find what appear to be CVN syllables,

as in [kòdõntú] 'stool'. These are only found in a highly-restricted environment, which

although complex can be defined precisely. The basic observation is that apparent CVC syllables

always have a nasal as the coda, and this nasal only occurs after nasal vowels and before oral stops

or affricates, as in (25).

(25) [kòdõntú

kàbu ̃́ŋgú

ku ̃̀mbáǃ

ko ̃̀ndóǃ ]

kò-dõtú

kà-bu ̃́gú

ku ̃̀báǃ

ko ̃̀dóǃ

NC1-stool

NC1-snake

climb\IMP

enter\IMP

stool

snake

climbǃ

enterǃ

Prenasalisation affects all oral stops and affricates (26), with the exception of the glottal stop and its

palatalised and labialised variants (27).

(26) [ìtʃi ̃́ntʃú

ùle ̃́nʒí]

ì-ci ̃́cú

ù-le ̃́jí

NC3-intestines

NC7-sun

intestines

sun

(27) [kàhi ̃́ʔi ̃̀

hʷa ̃́ʔʲ a ̃̀

tʃa ̃́ːʔʷ

a ̃́ĩ]

kà-hi ̃́'i ̃̀

hwa ̃́'ya ̃̀

caa ̃́'wa ̃́i

NC1-night

day_before_yesterday

NC6-sweat

night

day before yesterday

sweat

In what follows I will address two questions about these [ṼNC] sequences. The first concerns the

nature of the [NC] portion – should it be regarded as one or two segments phonetically. The second

question is whether the [ṼNC] sequence should be represented phonologically as /ṼC/, with the

nasal supplied by a predictable phonetic rule, or as /ṼNC/8.

Prenasalisation is fairly widespread in African languages, and Childs (2003: ???) describes it in

articulatory terms as follows:

The tongue is moved into position to form the closure, as for a normal stop. However there is a

lag in raising the velum, and so there is an intermediate period where the air still escapes

through the nose, giving rise to the nasal segment.

Given this description, we might expect the duration of the nasal component to be relatively short –

and this is just what happens in many Bantu languages, where the vowel lengthens before prenasalised consonants to compensate for the nasal 'giving up' its timing unit (Ladefoged and

Maddieson 1996ː 123). However in Cicipu the duration of the nasal portion of NC sequences is

usually quite long, sometimes up to five times the length of the preceding vowel, and often it is

even longer than a straightforward nasal consonant. This can be seen from the waveform in Figure

2.

8 A third possibility, of course, is /VNC/ with the vowel assimilating to the following nasal. This has been ruled out

because nasalisation generally spreads to the right in Cicipu (see §7), and because it does not account for the lack of

/ṼC/ sequences.

0.1754

0

-0.3539

0

0.936792

Time (s)

Figure 2 ìnámá yi ̃́bɔ ̃̀ ‘certain animals’

The arrow points to the [m:] in yi ̃́bɔ ̃̀ [ji ̃́mːbɔ ̃̀] ‘certain’– this is clearly longer than

either the [n] or the [m] of the word ì-námá ‘animals’, and in fact is as long as the entire [ájí]

sequence immediately before it. Such a discrepancy makes it hard to maintain that the nasal and the

following stop form a single segment.

In addition to the argument from length, the behaviour of the sequence with respect to voicing

strongly suggests that the NC sequence is not a single phonetic segment – the nasal portion is

always voiced, whether it precedes a voiced or voiceless plosive. As Ladefoged and Maddieson

(1996ː 123) point out “a change of voicing within a unitary segment is quite exceptional”.

Phonetically, then, it seems that the sound is best described as a sequence of nasal plus stop, rather

than as a prenasalised consonant. However that does not rule out the possibility that the nasal

portion of such sequences is supplied by a predictable rule – indeed Ladefoged and Maddieson

(1996ː 127) point out that the motivation for analysing an NC sequence as a prenasalised stop is

often phonological rather than phonetic.

Therefore we will now consider the evidence for the /ṼC/ analysis. The clearest motivation for this

analysis comes from their distribution. Since Cicipu has both oral and nasal vowels, and nasal

vowels do not generally occur directly before stops, it is possible to regard the nasal contoid in

words such as [kòdo ̃́ntú ] as conditioned by a combination of the preceding vowel and the

following consonant. The environment for prenasalisation is summarised in the phonological rule in

Figure 3. Hence the apparent CVC patterns are predictable and can be derived from CV syllables

involving the sequence of a nasal vowels and a non-continuant9.

9 It is not known how implosives behave with respect to prenasalisation – no words have been found with either a

nasalised vowel or a nasal before an implosive. According to Childs (2003ː ???), there is debate as to the value of

the feature [constricted glottis] for implosives, and so the rule here makes no firm prediction either way.

Figure 3: Environment for the prenasalisation

rule

[+nasal]

V

C

[-continuant]

[-constricted glottis]

There is a 'hole' in the distribution of nasal vowels (i.e. they do not occur before non-continuants),

and this hole can be filled by assuming the existence of the phonetically and typologically sound

rule given in Figure 3.

Although most instances of prenasalisation are found root-internally, as in the examples we have

discussed so far, the process does also happen, albeit rarely, across morpheme-boundariesː

(28) [mu ̃́ ɡʷàːnùkʷà

n

m-úu

gwàanùkwà

1S-FUT see\IRR

tʃé]

cé

NEG

I wouldn't know

[sayb001.102]

(29) [kɔ̀ɓɔ ̃́ː kè]

n

kɔ̀-ɓɔ ̃́ɔ k-è

NC1-axe

AG1-COP

it's an axe

[eamd002.054]

We would have to construct a prenasalisation rule such as the one given in Figure 3 to account for

these examples, quite independently of considerations of syllable structure in roots. The rule could

then be re-used to account for root-internal prenasalisation.

Further evidence comes from the reduplication process found in NC5 nouns10 derived from roots

with long initial consonants. The class 5 prefix takes the form ǹ- before roots beginning with short

consonants. If the root begins with a long consonant then one of two alternative strategies is

adopted, both of which can be regarded as ways to avoid triple consonant clusters, which are not

attested in Cicipu. The first strategy, which occurs with only a few monosyllabic roots, is for the

prefix to undergo a kind of metathesis, so that, for example, the plural of the 6/5 noun cí-llú 'neck'

10 This reduplication also occurs optionally with NC2 nouns, but it is NC5 that concerns us here.

is not ìn-llú, but mí-llú 'necks'. The second strategy, which occurs for all other roots with class 5

nouns, is to reduplicate the first syllable, but with the consonant shortened. So instead of ìnhhóiyú, we find ìn-hóihóiyú 'streams'.

Recall that C1ːV1C2V2 roots form class 2 and class 5 nouns with the structure ìn-C1[í/ú]C1ːV1C2V2,

where the vowel inserted between the reduplicated consonant and the original consonant is u if V1

is rounded, and i otherwise. So for example the root -ggɔ́dɔ́ 'lump' forms the class 5 noun ìngúggɔ́dɔ́ 'lumps', as shown below:

(30) [mɔ̀ɡːɔ́dɔ́]

[ìnɡúɡːɔ́dɔ́]

mɔ̀-ggɔ́dɔ́

ìn-gú-ggɔ́dɔ́

NC4-lump

NC5-REDUP-lump

lump

lumps

Of relevance here is the fact that if V1 is nasal, the inserted vowel may also be nasal – in other

words the [nasal] feature of V1 spreads onto the inserted vowel along with the [round] feature.

Unfortunately the corpus only contains three such words, and only one token of each. So it is

impossible to say at the moment whether the relevant factor is sociolinguistic variation, lexical

variation, or even 'free' variation within the speech of individual speakers. Nevertheless in two of

the three tokens nasal spread did occur, and one of these (32) also contained a prenasalised

consonant.

(31) [kàhːu ̃́ːtʃí]

[àhu ̃́hːu ̃́ːtʃí]

kà-hhu ̃́ucí

à-hu ̃́-hu ̃́ucí

NC1-cloud

NC2-REDUP-cloud

cloud

clouds

(32) [mɔ̀ɡːu ̃́ntú]

[ìnɡu ̃́nɡu ̃́ntú]

mɔ̀-ggúntú

ìn-gu ̃́n-gu ̃́ntú

NC4-short

NC5-REDUP-short

short thing

short things

The nasalisation on the first [ɡu ̃́n] in (32) cannot have come from the class 5 prefix – as (30)

illustrates, nasality does not spread on to the vowel after the stop. Instead it has been copied from

the first root vowel, just as in (31). Since the reduplication rule does not usually copy complete

syllables, only C1 and certain features of V1, the n in the second syllable of ìngúngúntú must have

come about as a result of a further application of the prenasalisation rule.

Lastly, there is also some evidence from loanwords to support the prenasalisation analysis. The

Hausa word mugu 'evil' has been borrowed as kò-múngù [kòmu ̃́ŋɡù]. Nasalisation spreads from a

nasal to the vowel immediately to the right, and this accounts for the nasalisation on the first root

vowel. This vowel seems to have in turn resulted in the nasal [ŋ] before the [ɡ], just as the rule in

Figure 3 predicts. Another interesting piece of evidence is provided by the loanword kà-ma ̃́ya ̃̀

[kàma ̃́j a ̃̀] 'elder', from the Hausa word manya 'elders'. The Cicipu word is pronounced without

a nasal consonant, suggesting that either (i) CVN is not one of the underlying syllable types in

Cicipu, or (ii) it is a possible syllable type, but only before non-continuants. One might have hoped

for more such evidence, but in all the other Hausa words with an NC cluster which have been

borrowed into Cicipu, the C is either a plosive or affricate11, and so does not allow us to distinguish

between prenasalisation and a true CVN syllable. This no doubt reflects a more general constraint in

Hausa.

Stating the environment for the prenasalisation rule as in Figure 3 is not quite sufficient to account

for all the data on prenasalisation. This is because not all phonetically-nasal vowels trigger

prenasalisation before stops. Vowels which have become nasalised because of a preceding nasal

consonant may appear before consonants and affricates without an intervening nasal segment, as

illustrated by mita 'squeeze', kù-mócì 'old woman'. It is only underlyingly nasal vowels which

result in prenasalisation. To cater for these examples the rule handling the rightward spread of

nasalisation must be ordered after the prenasalisation – in technical terms the rules are in a 'counterfeeding' relationship. Some roots beginning with a nasal such as /mĩto/ [mĩnto] 'shut mouth' do

contain a ṼNC sequence – these are assumed to have underlyingly nasal vowels just as the

examples in (25-26).

So far, all the data has been consistent with the idea that NC clusters are the result of a phonological

process of prenasalisation, so that the nasal consonant is not to be considered part of the underlying

representation of the roots concerned. We now turn to a problematic scenario for this analysis. As

well as the spread of nasalisation from nasals to vowels, there is evidence that nasalisation also

spreads from nasals to following plosives or affricates. This evidence is provided by the fact that

only a small number of voiceless non-continuants take part in NC clusters – it is much more usual

for the C to be voiced (see Table 10 for the exact figures). This fact seems to favour the “underlying

nasal phoneme” analysis – voicing would then spread to the right straightforwardly using the rule

introduced in the previous paragraph. If we wish to maintain the stance that [ṼNC] sequences are

underlyingly /ṼC/ then the analysis becomes rather complex here. First, voiceless plosives would

be responsible for the appearance of the nasal segment. Second, this nasal segment would then, in a

subsequent derivation, turn the tables on its creator and cause it to become voiced – in technical

terms the rules are in a 'feeding' relationship. Of course this means that the rule causing nasal spread

on to non-continuants has to be ordered before the prenasalisation rule, quite the opposite

conclusion of what was reached in the previous paragraph. Thus we would have two separate rules

of rightward-spread of nasalisation, applying at different stages and to different classes of

phonemes. This level of complexity is certainly not to be welcomed, but apart from this problem the

prenasalisation analysis holds up well. It should be noted that the restriction of NC clusters to

voiced C's is only absolute for velar plosives. Table 10 shows that there are quite a number of cases

of root-medial /nt/ clusters for both nouns and verbs. Consequently it may not be appropriate to

attempt to account for this kind of 'relative' distributional data using standard phonological rules.

The evidence assembled above largely supports the claim that prenasalisation is a phonological

process, and that [ṼNC] sequences are underlying /ṼC/, with the nasal segment supplied

predictably, according to an ordered rule such as that given in Figure 3. Nevertheless the resultant

nasal segment (which, as we have seen, can be quite long) contributes to syllable weight in weightsensitive processes. Two such cases are briefly discussed here.

Firstly, long nasal vowels do not seem to trigger prenasalisation. There are only three examples of

long nasal vowels preceding a consonant in the corpus, but they pattern consistently – none of them

have a nasal intervening between the vowel and the stop.

11 Or the ejective ts, which resolves to tʃ when borrowed in Cicipu.

(33) kà-hhu ̃́ũcí

kà-ti ̃́ĩti ̃́ĩ

kɔ̀ɡʷɔ ̃̀ɔ ɡʷɔ ̃̂ɔ

NC1-cloud

NC1-foreskin

NC1-crow

cloud

foreskin

crow

There does not seem to be any obvious reason why long vowels should not trigger pre-nasalisation,

unless the resultant nasal forms the coda of a CVC syllable. In this case the restriction would be

simply a matter of syllable weight: it is not unusual for languages to have special restrictions on

'super-heavy' CVVC syllables. The environment given in Figure 3 can be allowed to stand, with the

proviso that this more general constraint prevents it from applying to a long vowel.

Secondly, the tone pattern on verbs are sensitive to syllable weight. The habitual tone pattern has

already been mentioned in §2.3. Verbs with ṼNC sequences, as in (17), generally12 pattern with

other 'heavy' syllable patterns such as CVVCV and CVCCV. Similarly, for the realis tone pattern

such verbs also pattern with other heavy syllables in taking a falling tone on the first root vowel

rather than a high tone:

(34) ùbánà

ùkôo

ùko ̃̂ndò

u-bana-LHL

u-koo-LHL

u-kondo-LHL

3S-invite-RLS

3S-die-RLS

3S-enter-RLS

he invited

he died

he entered

In summary, prenasalisation in roots is a predictable phonological process, but the resulting nasal

segment is both longer in duration than might be expected and contributes to the weight of the

syllable in weight-sensitive processes. Given the complexity involved here, it is strongly

recommended that any competing orthographic choices with respect to ṼNC clusters are thoroughly

tested in the speech community.

Before leaving the topic of prenasalisation, it should be noted that a small number of noun roots

begin with an NC sequence, where C is a stop, exemplified by (35-36):

(35) ma ̃́-ndá

mi ̃́-ndá

NC4-calabash

NC5-calabash

calabash

calabashes

(36) wú-ntò

ví-ntò

NC7-guest_hut

NC8-guest_hut

guest hut

guest huts

The NC clusters in these words should not be considered products of the prenasalisation process, at

least not synchronically. We have already seen that vowels which are nasalised because of a

preceding nasal consonant do not go on to cause pre-nasalisation. And in any case, in (36) neither of

12 There are three exceptional verbs which are not yet understoodː yinda 'see', panda 'forget', and kanda 'mark'.

the prefixes has a nasal consonant.

2.6 Approximants

The ambivalent vocoids [i] and [u] can be analysed either as consonants /y/ and /w/, or as vowels /i/

and /u/. Given that the only unambivalent syllable type is CV, semi-vowels are analysed as

consonants when they occur in onset position, and as vowels when they occur in nucleus position.

2.7 Other word classes

The above discussion has concerned only noun and verb roots, which are usually made up of CV

syllables, with arguments for CVN and CVC. Other word classes, however have different

possibilities, in particular prefixes (nominal or verbal) and ideophones.

Nominal prefixes and subject agreement prefixes are all monosyllabic, and can be of the form V,

CV, or VN, as was illustrated in tables 1 and 2, repeated here for convenience.

NC1

NC2

NC3

NC4

NC5

NC6

NC7

NC8

NC9

C-initial kA-

A-

i-

mA-

N-/mi-

ti-

u-

C-/Ø-

ku-

V-initial kV-

V-

yV-

mV-

mV-

tV-

wV-

vV-

kʷV-

Table 5: Consonant-initial and vowel-initial noun class prefixes, repeated from Table 1

1S

2S

3S

1P

2P

3P

C-initial N-

C-/Ø-

u-

ti-

i-

A-

V-initial mV-

vV-

wV-

tV-

yV-

hV-

Table 6: Consonant-initial and vowel-initial person agreement prefixes, repeated from Table 2

With respect to syllable structure, the most interesting prefixes are NC8 and 2S, specifically the

allomorphs represented here as C-. The application of this prefix results in the lengthening of the

first consonant of the root, whatever this consonant happens to be. Any consonant can be

lengthened in this manner; a few examples are given in (37-38).

(37) z-zá

k-ká

c-cɔ́'ɔ̀

s-síró

NC8-person

NC8-woman

NC8-sheep

NC8-mane

person

woman

sheep

mane

s-sâabà

l-láttà

j-jântà

2S-want\RLS

2S-used_to\RLS

2S-sleep\RLS

2S-want\RLS

you(s.) want

you(s.) are used to

you(s.) slept

you(s.) crushed

(38) t-tá'à

[eamy036.001]

As we saw in §2.1, the first vowel of a vowel-initial nominal or verbal root either coalesces with a

noun or agreement prefix, or else is obligatorily preceded by a w- or y- 'dummy' consonant. For the

prefixes themselves, the situation is similar – if they are preceded by another prefix, then usually

(but not always – see §8.1) coalescence occurs. In connected speech they are usually elided with the

preceding vowel (again see §8.1). Utterance-initially, and sometimes in the middle of an utterance,

they are pronounced with a (non-phonemic) preceding glottal stop.

The NC5 and 1S prefixes are most often pronounced as syllabic nasals, but they may also occur with

a very short preceding [ĩ] vowel, especially utterance-initially. Arguments can be made both for /N/

and /ĩN/ as the underlying representation. Most of the time there is no vowel, and this argues in

favour of /N/. When the vowel does appear, this can be assumed to be a co-articulatory timing

effect, in much the same way as the prenasalisation discussed in §2.5, except in this scenario the

opening of the velar flap is delayed rather than anticipatory. On the other hand, a case can be made

for /ĩN/ by considering the conjunction ǹ 'and/with', which has the same phonetic properties.

Furthermore this conjunction and the NC5 prefix have similar allomorphs before long consonants,

both involving the vowel ĩː mĩ- for the nc5 prefix and ni ̃̀- for the conjunction, shown in (39-40).

(39) mì-nnú

NC5-bird

birds

[eamd004.009]

(40) sée

nì-t-tôonò

until and-2S-come_home\RLS

until you come home

[saat002.002.355]

If the vowel is analysed as being part of the underlying representation then these allomorphs

become the product of a straightforward metathesis process triggered by the need to avoid triple

consonant clusters.

Because of the short duration and infrequent occurrence of the ĩ vowel it is considered to be nonphonemic in all of these cases, and the underlying morphemes are therefore held to be /m/ for the 1S

and NC5 prefixes and /n/ for the conjunction. The transitional vowels that appear in examples such

as (39) and (40) take the [i] quality as a default – and in fact we have to posit something similar to

account for the epenthetic [i] vowels in the reduplication process discussed in §2.5.

This analysis also find support when one considers when another prefix occurs before the NC5 or 3S

prefixes. If the ĩ vowel was part of the underlying representation, and somehow suppressed

utterance-initially, then we might expect it to surface in this environment. On the other hand if it is

merely the result of an occasional co-articulatory timing effect, then it should not occur – if the

opening of the velar flap was delayed, then the first prefix vowel would simply lengthen until the

flap did open. In almost all cases that have been examined the ĩ vowel is not there, as in (41):

(41) 'á-nà

à-zá

PL-some NC2-

há-ǹ-kàcì

m-ì

AG2-NC5-hunting NC5-COP

person

there were some hunters [lit. 'people of hunting']

[sami001.016]

Cross-linguistically, ideophones are often phonologically 'deviant' in some way (Childs 1994ː 181).

In Cicipu ideophones are characterised by CVC syllables, which as we have seen do not normally

occur in the language. So far ideophones have been found with deviant codas containing nasal

consonants, the plosive p, and the fricative s. Some examples are given in (42):

(42) vɔp

splatǃ

pass

ɗo ̃́oŋ

pɔm

dʒáràs

very white

very black

wholly

like sand that is wet and cool

2.8 Word structure

Noun and verb roots in Cicipu are usually disyllabic, although there are still a significant number of

mono- and tri-syllabic roots. The monosyllabic roots all appear to have long vowels, and many are

demonstrably derived from former disyllabic roots (see §2.4).

A few words for birds and trees have four or even five syllables, but often these are reduplicated. In

the following tables Hausa loanwords are omitted because they have a markedly different

distribution from native Cicipu words, being more likely to have tri-syllabic roots. The distribution

is given in Table 7:

Syllables in root

Tokens

Examples

1

106

kò-lúu 'knee', kù-tɔ́ɔ 'hen'

2

520

kù-cíi.nó 'back', kù-dá.vù 'mortar'

3

94

mé-bbè.ríi.sè 'swift', cìc.cé.rè 'star'

4

16

kà-'a ̃́.gà.là.mì 'traditional bag'

Table 7: Syllable structure of noun roots

Verbs follow a similar pattern to nouns, with an even higher percentage of disyllabic roots. Several

monosyllabic verbs have grammatical as well as lexical meanings (e.g. yãa 'do', yoo 'be'), and the

remainder are all high-frequency morphemes. Again it is possible that historically these are derived

from disyllabic roots – for example koo [kʷoː] 'die' can be reconstructed as *kuwə for West Kainji.

Of the tri- and quadri-syllabic roots, it is likely that the majority were once bi-morphemic. In some

cases fossilised present-day derivational processes can be identified. In the two verbs with four

syllables gituwana 'inhale' and kusiyanu 'smell (with nose)' the infix -uw- and the suffixes -na

and -nu are present-day affixes, but it is not possible to derive the meanings of the verbs

compositionally. Similarly a number of trisyllabic roots appeared to be contain the infix -il-,

although they cannot appear without this affix (e.g. tobilo 'to cool liquid by repeatedly pouring').

If such verbs are analysed synchronically as disyllabic roots with an obligatory affix then the bias

towards disyllabic roots is even stronger than shown in Table 7.

In other cases, while it is not possible to identify grammatical morphemes in present day use,

patterns still emerge. For example, titɔmɔ 'thresh', ziza'a 'shiver', and zizaɓa 'tickle' all combine

a reduplicated prefix with an inherently iterative meaning. Similarly cekete 'crush into pieces',

pɔkɔtɔ 'brush off' and valata 'wag tail' all end in -tA, and are also amenable to an iterative

interpretation. These do not seem to be productive processes/affixes in Cicipu now, but they may

well have been in the past. If we exclude such verbs from the count, as well as the less speculative

cases mentioned above, then there are probably not many more than a dozen irregular verbs with

more than two syllables.

Syllables in root

Tokens

Examples

1

18

caa 'give', yãa 'do'

2

311

na.ha 'leave', la.sa 'greet'

3

69

hee.pi.ye 'ask', mi.ri.ɗa 'twist'

4

3

gi.tu.wa.na 'exhale', ku.si.ya.nu 'smell (i.e.

with nose)'

Table 8: Syllable structure of verb roots

Disyllabic verbs in Bantu languages are usually considered to have CVC roots, with the 'final

vowel' V2 supplied according to rule. In some languages this vowel has a constant value /a/, in other

languages it is a copy of one of the root vowels (Lutz Marten p.c.). In Cicipu, as with other West

Kainji languages (e.g. C'Lela – Steve Dettweiler p.c.), the situation is more complex. In just over

half (148 out of 276) of disyllabic verb roots V1 and V2 have identical vowel qualities, but in the

remainder V2 must be lexically-specified. This has morphological consequences since if the final

vowel in Cicipu is actually part of the root, then the causative <is> and iterative <il> morphemes

must be analysed as true infixes rather than suffixes. The verb roots in examples (43-44) are pina

'shave', pino 'boil', dooho 'disappear', and goonu 'help'.

(43)

ù-pín<ìl>à

ù-pín<ìl>ò

3S-shave<ITER>

3S-boil<ITER>

he shaved [many times]

it boiled [many times]

[2008-02-12.008]

(44)

ù-dôoh<ìs>ò

ù-gôon<ìs>ù

3S-disappear<CAUS>

3S-help<CAUS>

he caused s.t. to disappear

he had s.o. to help

[2008-02-12.008]

2.9 Summary

While noun and verb roots in Cicipu may begin with a vowel, words are always consonant-initial on

the surface. Roots with long vowels may be analysed as two syllables CV.V, roots with

prenasalised stops may be analysed as CVN.CV. A small number of roots begin with an NC cluster

(e.g. 35-36), but once the prefix is taken into account they syllabify as CVN.CV.

If we may talk of underlying syllabification, then Cicipu allows CV, V, and N syllables in noun and

verb roots. On the surface, however, the possibilities are CV, CVC (where C2 is an ambisyllabic

long consonant) and CVN. Only the first of these three may occur word-finally.

3

Consonants

3.1 Phonemic inventory

The consonant phonemes of Cicipu are given in Table 9.

Table 9 – Consonant chart (phonemic)

Bilab Lab-dent

Stops p b

Impl

ɓ

Affric

Fricat

v

Nasals m

Liquid

Rhotic

Appx

Dental/Alv

td

ɗ

Post-alv

Palatal

Velar

k g kʷ gʷ

Labio-velar

Laryng.

ʔ ʔʷ ʔʲ

tʃ dʒ

h hʷ hʲ

sz

n

l

r

j

w

Although the coronal consonants in the above table have been labelled 'dental/alveolar', at least /d/

and /t/ were found to be dental (and laminal), rather than alveolar. This was only checked for one

speaker, however. It is not yet known whether /n/ and /l/ are alveolar or dental, although they might

be expected to pattern with /d/ and /t/. Unlike some languages the voiced stops /b/, /d/, and /g/

continue their voicing during the closure. Glottal stops often fall short of complete closure, other

than when they are long, resulting in creaky voiced vowels instead (this is fairly common according

to Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996: 75).

The implosive /ɓ/ seems to be a true implosive rather than the creaky-voiced Hausa ɓ. The voicing

appears normal rather than biphasic and the amplitude of the voicing increases towards the end of

the closure indicating the lowering of the larynx (see Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996: 84).

The phone [f] is extremely rare in Cicipu. It has only been found in one loanword felle 'cut

branches' (Hausa falle) and one ideophone kèfée 'way of walking, k.o.', which may also be

borrowed. Because of its rarity and marginal distribution, f is not analysed as a phoneme here. This

restriction to loanwords is something of a conundrum since the standard Hausa [f] phone is

apparently not found in the Western Hausa dialect spoken in the Acipu area (Newman 2000: 393),

which has [h/hʷ] instead.

3.2 Allophones and general phonetic rules

The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/ sometimes undergo lenition to [ɸ] and [β] when they occur intervocalically, especially in quick speech. For example /yapu/ 'two' may surface as [jaɸu], and /jiibo/

'have breakfast' as [dʒiːβo]. This inter-vocalic distinction between voiced bilabial and labiodental

fricatives is a common feature of Bantu languages (Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996ː 139). This

lenition does not appear to be found with non-labial plosives, a split which is common crosslinguistically (Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996ː 17).

As well as the labialised and palatalised phonemes which appear in Table 9 there are a number of

non-phonemic allomorphs which also have these modifications. /m/ and /v/ have labialised

allomorphs [mʷ] and [vʷ] before rounded vowels, while /k/ and /g/ have palatalised allomorphs [kʲ]

and [gʲ] before front vowels. Before rounded vowels /k/, /'/ and /h/ do not contrast with their

labialised counterparts, and so the underlying consonant in such sequences cannot be determined.

Similarly before front vowels /'/ and /h/ do not contrast with their palatalised counterparts.

The phoneme /t/ is sometimes, but not always, realised as [tʃ] before [i], for example in the verb

tiyo 'get'. [tijo] seems to be considered the 'correct' form by native speakers. Ladefoged and

Maddieson (1996ː 90) point out that affricates are an “intermediate category” – every stop has a

certain amount of frication, and while it is usually considered as part of the release of the stop, there

is no discrete phonetic boundary between a stop and its corresponding affricate. So it is not

surprising to find [tʃ] and [t] occurring in 'free' variation.

The fricative [ʃ] is non-phonemic but does occurs as an allomorph of /s/ before [i]. Individuals seem

to vary quite a bit in this regard. With some the [ʃ] is very strong, with others it is less so. There

may also be dialectal differences, with Tidipo speakers seemingly more likely to have a strong [ʃ]

than Tirisino speakers13.

There are only two phonemic nasals in Cicipu, /m/ and /n/. [ŋ] and [ɱ] are found as allophones

before velar and interdental consonants respectively.

/r/ is realised as a flap/tap14 [ɾ] utterance-medially. Utterance-initially, and when lengthened (see

§3.4), it is realised as an approximant [ɹ] (or an r-coloured vowel [ɚ]). Often this segment is

followed by a flap/tap, so that the sequence is [ɹɾ] or [ɚɾ].

(45) [ɹ̃̀e ̃́

ⁱ ],

[kàdámá

kéɹ̃̀ɾe ̃̀ⁱ ]

r̃̀réin,

kà-dámá

ké-r-rèin

NC8-

NC1-word AG1-NC8-town

town

towns, the word 'towns'

[eamy032.024]

Sometimes the flap/tap surfaces as the retroflex/post-alveolar [ɽ], especially after the vowel /a/, but

unlike Hausa there does not seem to be a phonemic distinction between the coronal and postalveolar flaps.

The approximants /y/ and /w/ have nasalised allophones [j] and [w] which occur in the

neighbourhood of nasalised vowels. Note that the former differs from the nasal [ɳ] since it does not

have a closure.

As well as the allomorphic variation found in individual phonemes, there are alternations involving

two different phonemes. In some cases this can be put down to dialectal or even idiolectal variation,

but in other cases there is no obvious pattern. The alternation between /c/ and /t/ has already been

discussed. Another such case is the alternation between /l/ and /n/ found in the verbs laha/naha

'let' and lapa/napa 'know', amongst other roots. Naha is used in the Tikula dialect and laha in

Tidipo. Within the Tirisino dialect either form is possible, and there is even variation within the

same family. The two Tirisino speakers I have observed using laha are both elderly, so it may be

that naha is the newer form in Tirisino. Lapa is found in Tirisino and napa in Tikula.

3.3 Distribution in noun and verb roots

The distribution of the consonant phonemes given in Table 9 depends on both the word class and

the position of the phoneme in the root. Table 10 shows the distribution of consonant phonemes in a

lexicon containing 626 native noun roots and 358 native verb roots. Multi-morphemic and

borrowed words were not included in the count. Although no statistical analysis has been carried

out, certain figures do stand out and these have been highlighted in the table. For root-medial nasals

and non-continuants the figure in brackets shows how many of the tokens in that cell are part of NC

13 The presence of the [ʃ] sound in English is a linguistic stereotype for the Acipu, who sometimes refer to the English

language using the metonym ù-pépí 'wind'.

14 It is not known whether this sound is a flap or tap (See Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996ː 230-231 for a proposed

distinction between the two).

consonant clusters.

N initial N medial N total

V initial V medial V total

Overall total

p

29

19 (2)

48

25

14 (0)

39

87

b

20

26 (13)

46

7

10 (3)

17

63

ɓ

7

4

11

5

9

14

25

t

37

46 (7)

83

32

57 (11)

89

172

d

30

30 (15)

60

18

14 (6)

32

92

ɗ

13

22

35

8

21

29

64

k

81

6 (0)

87

36

7 (0)

43

129

kw 11

1 (0)

11

0

2 (0)

2

13

g

30 (22)

57

15

8 (6)

16

69

gw 2

3 (2)

5

1

8 (8)

9

14

'

63

81

25

23

48

129

'y 2

5

7

0

0

0

7

'w 2

1

3

2

9

11

14

c

38

25 (2)

63

25

1 (0)

26

89

j

21

8 (5)

29

9

1 (1)

10

39

v

11

13

24

14

10

24

48

s

52

31

83

30

33

63

146

z

16

10

26

14

4

18

44

h

20

0

20

22

2

24

44

hy 1

0

1

1

0

1

2

hw 0

0

0

0

0

0

0

m

13

52 (16)

65

10

16 (3)

26

91

n

15

65 (30)

80

6

55 (20)

61

141

l

28

47

75

12

40

52

127

r

23

49

72

5

15

20

92

y

41

51

92

14

10

24

116

w

9

11

20

4

37

41

61

27

18

Table 10: Distribution of consonant phonemes according to word class and root position

Some of the distributional restrictions can be put down to the rarity of the phonemes in question.

For example /'y/ is a very rare phoneme (only seven tokens altogether), so it is not all that

surprising that it is not found in verbs. /hy/ is not attested root-medially, but again this is very rare.

/hw/ occurs only in the noun tù-hwí'í 'C'Lela'15 and in the time adverb hwa ̃́'ya ̃̀ 'day before

15 This word was excluded from the above count. It is not known to be borrowed, but given that it refers to the name of

yesterday'.

Some of the more common phonemes also have distributional restrictions, and these are more likely

to be significant and not just gaps due to a limited sample size. One of the most striking restrictions

is that /h/ very rarely occurs root-medially. There are only two tokens out of 44 – dooho 'disappear'

and naha 'leave'. The phoneme /h/ is also found word-medially in the numeral tóríhi ̃̀ and the

time adverb rúhu ̃̀ 'last year'.

The affricates /c/ and /j/ are rare root-medially, especially in verbs. Both the examples of rootmedial affricates in verbs involve trisyllabic roots of uncertain derivation: /kucɔ'ɔ/ 'shake off' and

/mɔnjuwɔ/ 'glare'.

As has already been mentioned in the discussion on prenasalisation (§2.5), voiceless noncontinuants (plosives and affricates) are much less likely to be found in NC clusters than voiced

non-continuants. This is especially clear for the velar plosives, where /k/ is not found in NC clusters

at all. In contrast root-medial /g/'s are largely limited to such cluster. Quite apart from

considerations of prenasalisation, it should be noted that velar plosives are rare root-medially.

The next two tables show examples of nouns and verbs containing all the phonemes except /hw/.

Apart from this one exception, all the phonemes contrast root-initially in native Cicipu nouns as

demonstrated in Table 11.

a language this would not be surprising.

p

ù-pácí

difficulty

b

kà-bárá

old man

ɓ

mà-ɓásà

mole (on skin)

t

kà-tádá

palm (of hand)

d

kà-dábá

bush/countryside

ɗ

ù-ɗángà

tree

k

mà-kántú

knife

kw

m̃̀-kwá'á

orpheme

g

ù-gálù

side

gw

mà-gwáwá

deaf/mute

'

cì-'ádì

trap

'y

mɔ̀-'yɔ́'yɔ́

fish

'w

ù-'wîi

distance

c

kà-cá'ùn

husk (of maize)

j

kù-jénè

river

v

kà-várá

goat hut

s

kù-sáyú

spear

z

à-zá

people

h

cì-hávì

scratching

hy

à-hyán'àn

arrows

hw

tù-hwí'í

C'Lela language

m

kà-mángá

rope

n

ì-námà

meat

l

kà-lánà

scar

r

kà-rákátáu

heel

y

kà-yáyù

root

w

mà-wáa

dog

Table 11: Root-initial consonant phonemes in nouns

Apart from /'y/, /kw/ and /hw/ all the consonant phonemes contrast root-initially in native Cicipu

verbs. /kw/ occurs root-medially in the verb dukwa 'go' and cukwa 'praise' but neither /'y/ nor /hw/

are found in verbs at all. This is not really surprising given their overall rarity.

p

pasa

cross

b

bana

invite

ɓ

ɓasa

slap

t

tasa

meet

d

dasa

castrate

ɗ

ɗasu

soak

k

kanda

mark on wall

g

gava

kick

gw

gʷ iya

can

'

'etu

dry by hanging out

'w

'waa

pass

c

ca'a

harvest

j

janta

crush

v

vasa

hit

s

saɓa

embrace

z

zaa

find

h

hala

coil

hy

hyãa

say

m

mata

give birth

n

naha

leave

l

lawa

escape

r

raa

eat

y

yaa

arrive

w

waana

twirl

Table 12: Root-initial consonant phonemes in verbs

3.4 Length

While many languages have long consonants, it is rare (although not unheard of) for them to occur

root-initially and word-initially (Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996ː 93). As with Central Kambari

(Crozier 1984) any consonant can be lengthened in Cicipu, even if this means considerable phonetic

changes in how the phoneme is realised (see the discussion of /r/ in §3.2). The difference in length

between short and long consonants is relatively mild, with the lengthened often no more than half as

long again as its counterpart16. The distinction often seems to be neutralised altogether in normal,

fast, speech.

The waveforms in figures 4-8 demonstrate the length differences for the nasal /n/, the lateral /l/,

16 Ladefoged and Maddieson (1996ː 92) note that cross-linguistically long consonants tend to be longer than short ones

by between 1.5 to 3 times.

and the voiceless plosive /k/. The words in figures 4-7 all belong to NC8, which has either Ø- or Cfor allomorphs. The former occurs with Ø-náatà 'small spider' (Figure 4) and Ø-lóokàcíi 'time'

(Figure 6), resulting in a short initial consonant. The latter occurs with n-náa 'cow' (Figure 5) and

l-lámà 'noise' (Figure 7), resulting in a long initial consonant.

n

a:

t

a

0

0.595667

Time (s)

Figure 4: Waveform of náatà 'small spider'

n:

a:

0

0.597313

Time (s)

Figure 5: Waveform of nnáa 'cow'

l

o:

k

a

c

i:

0

0.604

Time (s)

Figure 6: Waveform of lóokàcíi 'time'

Figure 8 demonstrates the difference between an utterance-medial short and a long /k/:

(46) kà-dámá

ká-k-kà

NC1-word AG1-NC8-woman

l:

a

m

0

0.6005

Time (s)

Figure 7: Waveform of llámà 'noise'

a

the word 'woman'

[eamy032.014]

k

a

d

a

m

a

k

a

0

k:

a

0.853604

Time (s)

Figure 8: Waveform of kàdámá kákkà 'the word “woman”'

As can be seen from the waveform in Figure 8, long consonants are not formed simply by the

repetition of short ones. A long /k/ only has one period of closure and one period of release, and it

apparently differs from a short /k/ only in length of the closure. The difference between long and

short voiceless plosives is easy to hear utterance-medially, but difficult (perhaps impossible) to

detect utterance-initially, since the lengthening is confined to the closure. For some languages it is

possible to detect the differences between short and long voiceless plosives utterance-initially

(Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996ː 94), perhaps because of a change in amplitude of the following

vowel. This has not yet been tested for Cicipu, although it would be relatively simple to do.

Most of the long consonants are formed by an extension of some (as in /k/) or all (as in /n/ and /l/)

of the short consonant. However as discussed in §3.2, in the case of /r/ there is a qualitative

difference between the long and short variants – short /r/ is a tap/flap [ɾ] utterance-medially but

long /r/ is realised as an approximant [ɹ] (or an r-coloured vowel [ɚ]), optionally followed by a

flap/tap, giving [ɹɾ] or [ɚɾ] as shown in Figure 9:

The majority of long consonants in Cicipu words are ambi-morphemic, although as discussed in

§2.3 they are true long consonants rather than simply sequences of short consonants. They arise

from the application of the C- lengthening allomorph of the NC8 prefix to a noun root beginning

with a short consonant. All the examples in the waveforms given above are of this kind.

Long consonants in noun roots are mostly found root-initially. Out of 626 native Cicipu noun roots,

51 start with a long consonant. Most of these are likely to have arisen through the reinterpretation of

an NC8 C- prefix as part of the root, in conjunction with the addition of an additional noun prefix, so

that, for example, *g-gombo 'bat' > *ko-g-gombo > kó-ggòmbò. Occasionally the NC8 prefix is still

analysable, as in the case of kà-ddá'u ̃̀ 'guinea-corn husk':

(47)

kà-d-dá'u ̃̀

d-dá'u ̃̀

NC1-NC8-guineacorn

NC8-guineacorn

guineacorn husk

one guineacorn plant

In this case the kà- is an example of what are sometimes called 'augments' or 'pre-prefixes' in the

Bantu literature.

k

e

r

r

0

ein

0.386021

Time (s)

Figure 9: Waveform of ké-r-rèin 'of towns'

Twelve of the fifty-one nouns with root-initial long consonants begin with /k/ alone. Given that the

NC1 prefix kA- is the most common by far, it is likely that a number of these words had kAprefixes originally. On the addition of an extra pre-prefix, the original prefix vowel was lost. So for

example. we might derive má-kkàngà 'small drum' as followsː *ka-kanga > *ma-ka-kanga > mákkàngà .

Long consonants in verbs are rare. They do not occur root-initially, and there are only a few

examples root-medially – 16 out of 358 verbs. The only long consonants attested are /t/ (eight

tokens), /l/ (four), /n/ (two), /w/ and /'w/ (one each). The meanings of some of the verbs suggest that

the long consonants have come about as a result of the fossilisation of affixes. For example tanna

'descend' may have been derived from *tana plus the present-day directional suffix -na. Similarly

the /l/ examples kalla 'clear', kullo 'burn', 'isilla 'insult' and hullo 'blow' are all

amenable to an iterative interpretation, suggesting derivation from the present-day iterative infix

<il>. There is no present-day verbal affix containing /t/, but recall the examples of trisyllabic roots

discussed in §2.9, where a historical affix -tA was postulated. Many, if not all, of the verbs with

long /t/ are open to an iterative interpretation, for example hatta 'yawn', jitto 'blink', yɔttɔ

'impersonate', hɔttɔ 'huddle round fire', and sɔttɔnu 'urge'. There may also be synchronic

evidence of this process: the usual way to add a directional component of meaning to the verb is by

adding the suffix -nA, but for the verb dɔnɔ 'follow' *dɔnɔ-nɔ is ungrammatical – instead we find

dɔnnɔ.

3.5 Cross-linguistic comparisons

Compared to its close relatives Central Kambari and Tsuvaɗi, Cicipu has a rather simplified

inventory of consonants. The labiovelars gb and kp are missing17 as are the affricate ts and the

fricative ʃ. Sound correspondences exist between Kambari /ts/ and Cicipu /t/ (Table 13), and

between Kambari /ʃ/ and Cicipu /s/. Labiovelars in Kambari are rare and no relevant Cicipu

cognates have been found.

Gloss

pour

belly

obtain

buttock/

thigh

turn.around/ mat

oscillate

Cicipu

tuun

kò-túmó

tiyo

kà-gúutù zito

ì-táatú

mò-tôon

Kambari

tsun

ə́tsɨ̃́mə́

ts̠ɨrə

àa-gùtsû jits ə

íivá'átsú

mə̀-tsə̃̂n

Tsuvaɗi

tsun

ho-tsimo tsuro

haggutsu

i-vatsu

mo-tsso

Gloss

buy

ear

we

three

go.back

sleep

Tirisino

tila

kù-tívì

óttù

tâatù

gitu

la t

a

C. Kambari

tsɨla

ùutsɨ̃̀vû

ə̀tsú

tà'àtsú

gitsə

la n ts

a

Tsuvaɗi

tsela

u-tssuvu òtsú

ta'ɔtsu

la

a

saliva

t

ts

Table 13: ts~t Kambari/Cicipu correspondences

17 This has been confirmed independently by Israel Wade, a native speaker of ut-Ma'in, another West Kainji language

which does have labiovelars.

Gloss

redness

fart

feather

pestle

song

rainy

season

twin

Tirisino

ù-sílá

suwon

kàsín'ín

ù-síin

ì-sípá

ru-úsì

mè-pésé

C. Kambari

ùu-shìlî shuwə

áaúusshín'ín shínyín

íi-shípá lyùushî

Tsuvaɗi

u-shiili

hashi'in

ma-shin

vi-shipa lyuushi

Gloss

four

wring

rot

mosquito

weep

Tirisino

nósì

pisa

sama

sìpíyú

sɔɔn

C. Kambari

nə́əshín

pisha

shama

sshìpɨ̃̀r shon

û

Tsuvaɗi

noshin

pusa

shama

vishipiru

mə̀píshɛ̃̀

Table 14: ʃ~s Kambari/Cicipu correspondences

4

Vowels

4.1 Phonemic inventory

Closed

Mid-Closed