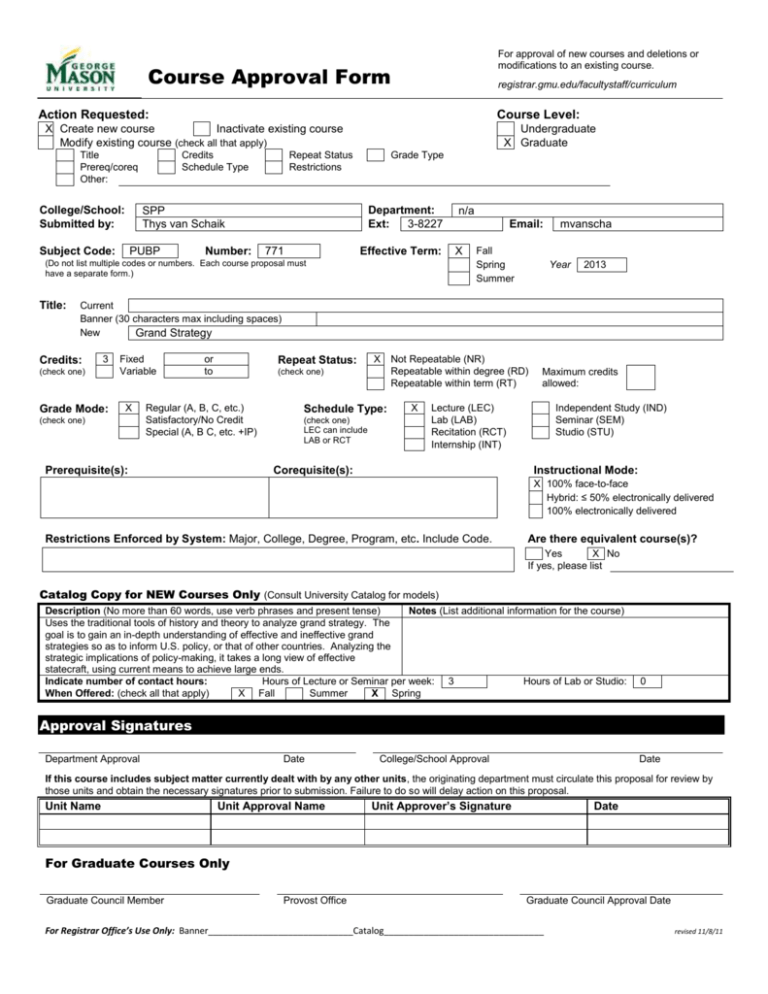

PUBP 771 - Office of the Provost

advertisement