Neutrality is inconsistent with the values of tolerance

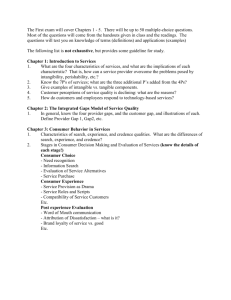

advertisement

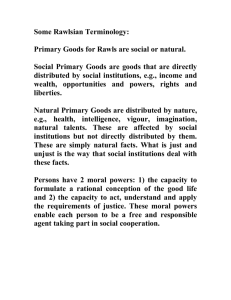

WHY A TOLERANT SOCIETY SHOULD NOT BE ENCOURAGED Here we will look at various arguments against promoting tolerance in society (1) WOLFF ON WHY INDIVIDUAL AUTONOMY IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN TOLERANCE: R.P. Wolff points out that tolerance is a virtue of pluralist democracies. o But what this really means is that the different communities that make up a pluralist society are represented in the democratic process, but the individuals within the, or even outside of any, community is not represented in the process at all. o There is no acknowledgement of the maverick individual. Wolff argues that this view of tolerance is grounded in the conservative views of Burke and Durkheim. These views argue: o Rather than considering a human to be an individual seeking meaning in a social environment, instead a human is first and foremost a member of the social community and an individual only secondarily. o A human is fully human within a social group; individuality is only pathological – it is the way we feel about ourselves, rather than what we are by nature. o Wolff gives the example of modern cosmopolitan cities like New York and London to show that his fears are correct: in these cities we find a huge variety of individuals, but each individual can find his or her niche in particular groups that serve their particular social way to be. In R.P. Wolff’s view: tolerance, in practice, contradicts the aims of JS Mill’s liberalism and the value of both individual autonomy and humanity. Contrast this with Barry’s argument for a tolerant society over individual autonomy – which view do you think is correct (or at least better argued)? (2) LORD DEVLIN ON THE NECESSITY FOR INTOLERANT MORALITY IN SOCIETY Lord Devlin argued that preserving and enforcing common moral values is part of the government’s business, and that failing to do so would lead to the disintegration of society. Devlin argues that: 1. Morality is essential to the welfare of society. o ‘There is disintegration when no common morality is observed and history shows that the loosening of moral bonds is often the first stage of disintegration’ 2. Morality is social, not private. o ‘The suppression of vice [immoral acts] is as much the law’s business as the suppression of subversive activities;’ 3. It is the business of government to look after the welfare of society. o ‘It is no more possible to define a sphere of private morality than it is to define one of private subversive activity.’ 4. So it is legitimate for government to pass laws on the basis of preserving moral values. o ‘Suppose a quarter or a half of the population got drunk every night, what sort of society would it be? You cannot set a theoretical limit to the number of people who can get drunk before society is entitled to legislate against drunkenness.’ This means not tolerating practices, and perhaps discouraging beliefs, that are in conflict with these moral values. Devlin’s argument points to the importance of social cohesion. Objections to Devlin: Devlin appeals to moral agreement, not to moral truth: o JS Mill would respond that in Devlin’s society, we will not get at the truth about morality and correct our mistakes. We need to allow experiments of the living in order to find any truth concerning morality. o Social morality may well need to change, as it might be inhibiting individual and social welfare. o For example: Devlin was arguing against was the legalization of homosexuality between consenting adults. Has this law led to the disintegration of social morality or society itself? Or is social morality better because it no longer condemns homosexuals? We can also object that ‘the welfare of society’ is not a value to be protected at any cost: o Perhaps society’s morality shouldn’t be enforced if it infringes people’s autonomy. This would be the case for Mill as he has a metaphysical commitment to human progression. o Or, following John Rawls, we can argue that the common morality that should be encouraged is one of tolerance. This common morality is based around the fairness of the law in allowing people to practice their own beliefs without their practices restricting others. But these arguments for tolerance from Mill and Rawls rest on the questionable assumption that people are equal, reasonable and autonomous. o If they are not, treating them as such could lead to misery and social breakdown. o In this case it could be argued that people need strong moral guidance, they need to be told the difference between right and wrong, between what is acceptable and what is not, or they will not be happy. (3) RELIGIOUS TOLERATION MIGHT NOT BE DESIRED Some might argue that tolerance will not help us discover religious truth or better ways of living, while intolerance may help us preserve them. o For example, many religious believers would see sexual promiscuity as being a defect of liberal society, leading to teenage pregnancy or pregnancy resulting in one night stands, hence leading to the breakdown of the family unit and a worse life for the child. o Being intolerant of sexual promiscuity would preserve the religious ‘truth’ of procreation (having sex in order to reproduce, after marriage) over fornication (sex for pleasure) would avoid this. The could also be put forward a variation of Lord Devlin’s argument: tolerating a variety of religious lifestyles and practices may contribute to the disintegration of society. o The example above is again relevant here, where some protestant Christians do not condemn those who have sex before marriage, others would argue this would lead to a worse society. We have also seen the limits of tolerance: it would be difficult for a liberal society to tolerate those religious practices (and laws) that would undermine an individual’s autonomy. However, as Barry argued, where individuals autonomously submit to such religious laws, then it would be intolerant to force them not to. o So if a Muslim chooses to have a legal case heard and decided in a sharia court, under Islamic law, it would be intolerant to prevent this. o On the other hand, if Islamic law violated the rights of the individual under society’s law, it is hard to see how a liberal society could allow Islamic law to be used. This highlights the problem of the enacting of tolerance in a religious context. These points can be used directly against LOCKE’s separation of the sacred and the secular and MILL’s argument for experiments of the living. (4) WHY THE NEUTRALITY OF A TOLERANT SOCIETY CANNOT BE ACHIEVED The key question here is: should government be neutral on the question of the good life, or of what gives value to life? John Rawls argues a tolerant society should be neutral: o o o o Rawls argues that for a society to be tolerant it must be ‘neutral’ between conceptions of the good life. A tolerant society will not exercise power (e.g. through legal or social sanctions) except by appealing to reasons that everyone reasonable can accept. This would avoid imposing unfair laws. To enforce a value or policy on the basis of reasons that depend on your own particular conception of the good, reasons that others would reasonably reject, is to be intolerant. Government should be neutral – social structures and laws must not favour one conception of the good over another. Problem #1 – The tolerant society need not be neutral Neutrality is not needed in the public sphere, as long as diverse views are tolerated in the private sphere: o This is the ‘permission’ conception of tolerance – diverse views are allowed to exist within a society that, on the whole, disagrees with them. o An intolerant society is only one that tries to get citizens to live – not just in public life, but throughout their lives – in accordance with its conception of the good. A response could be that genuine tolerance requires greater recognition and equality, and the state should be responsive to all conceptions of the good equally. o In practice, this is only possible if it is neutral. o For example, as Rawls argues, laws are passed on the basis of reasons that everyone can accept. No particular conception of the good enters into public life. Rawls’ argument lends favour to the Qualitative Equality model of the Respect conception of tolerance – here, diversity of cultural identities are acknowledged, all citizens agree to universal values. o However, this form of tolerance surely still recognises a ‘particular conception of the good’ in public life – i.e. the universal values. Hence it is not neutral in the way Rawls suggests. Rawls appears to be getting at the esteem conception of tolerance, but this has not (historically) been enacted in a society as a whole. Perhaps this is what we should be aiming for, but others might argue that this too idealistic – not all citizens are equal, reasonable and autonomous Problem #2 – Neutrality is inconsistent with the values of tolerance Joseph Raz argues that the point of tolerance is to respect and encourage autonomy. o However, neutrality undermines autonomy, because people will not be able to pursue certain ways of living if society is completely neutral. o Some conceptions of the good need state support in order to allow people to live according to those conceptions. o For example, some believe art forms part of a good life. In the UK many arts, such as the theatre and art galleries, are dependent on government funding to sustain them.But if government is neutral it would not be able to help fund the arts in society since it is not meant to favour one conception of the good over another. If the good can’t be sustained, then it can’t be pursued. The state should preserve a range of valuable options for individuals to choose between: o Without valuable options, the value of autonomy diminishes (we can’t pursue the good). o Of course, options may only appear valuable within certain conceptions of the good. o And so in this sense, society cannot remain neutral between conceptions of the good. We can object that this is not to abandon neutrality – society is just ensuring that conceptions of the good are preserved. If it would do this for any conception of the good, then surely it remains neutral. But this overlooks the point that society must appeal to values that not everyone shares, while neutrality requires that laws are based on reasons every reasonable person can accept. Problem #3 – Neutrality is not itself a neutral ideal Rawls’ appeal to neutrality is not neutral in itself; it requires favoured values on his part: o This is because Rawls argues that while neutrality is not part of the good for everyone, Rawls argues that every reasonable conception of the good accepts the project of basing society on ‘reasonable agreement’. o But this requires accepting the values of equality, reason and justifying power to individuals. o Unless a conception of the good ranks freedom more important than truth, say, why should its believers consent to giving only reasons all can accept rather than reasons based in their conception of the good? o We can argue this is not neutrality – Rawls in putting forward his very own conception of the good. Further, to say conceptions of the good that don’t accept these values are ‘unreasonable’ is itself unreasonable: o Rawls defends his idea of what is reasonable in terms of the ‘burdens of judgment’ – the fact that reasonable disagreement over basic values is an inevitable feature of social life in diverse societies. And so it is better to be fair and neutral since others will disagree as to what the basic values should be, thus ruling out a universal acceptance of a conception of the good. o However the burdens of judgment should allow us to say that ideas of freedom, equality and reasonableness are themselves contentious. For example, fundamentalists could argue that it is reasonable to believe that individuals’ reason is weak and sinful (used for pride, self-interest, etc, not for what is truly good), and so should not be trusted. o Rawls’ idea of the reasonable will appeal only to those who are already reasonable by its standards – but this standard can be (reasonably?) contested. o So, again, Rawls’ idea of neutrality is not itself neutral. This doesn’t entail that society can’t be tolerant, only that we shouldn’t understand tolerance in terms of neutrality. (5) MARCUSE ON REPRESSIVE DESUBLIMATION Herbert Marcuse argues that this technological age has created false needs: o We come to define what we need in terms of what will contribute to economic and technological progress, i.e. consumerism: the consumption of products, living according to what increases the flow of money in a country. o We have less freedom but because the false needs are satisfied we feel happy anyway. o We are losing our will to oppose government and to effect radical change in society because these false needs subdue us. Because of this there are so few ‘experiments of the living’ that strike out against the norms put forward by state and culture. o Anything really different or dangerous is just repackaged as a commodity and derives of meaning. o E.g. Che Guevara becoming a fashion accessory when he was a guerrilla terrorist. We used to sublimate our repressed sexual energy into art o Taking a Freudian view, Marcuse argues that our sexual drives were once repressed in society – we didn’t have many acceptable sexual freedoms – and so this sexual energy was redirected into forms of creativity (i.e. higher culture). o This allowed us to express rebellion against societal norms since in this sublimation of our sexual energy we remained conscious of society’s repression of our drives. Now all we have is repressive desublimation: o This is because we now have more sexual freedoms – but our sexual energy is only expressed as sex itself, rather than creativity. o These apparent freedoms have actually robbed as of a true aim of freedom since this means higher culture has been commodified and we have lost our creativity and our rebellion. o By giving us easily satisfied false needs, we have succumbed to ‘desublimation’: there is no need to sublimate our energies into art and action – if the system makes us happy, why conduct an ‘experiment of the living’? o The satisfaction of this desublimation weakens the rationality of protesting against society. Pornography as an example of repressive desublimation: o Marcuse refers to ‘the social steering of sexuality through controlled desublimation’ and ‘the plastic beauty industry’ as promoting ‘”legitimate” satisfaction’ [i.e. the kind of dumbed down satisfaction that helps the state economically]. o Pornography re-sexualises the body, particularly female bodies, present women as sexual objects and accords such representations an exchange value in the marketplace. o Here the body is a commodity and the representation of females and males is dehumanising: women are represented as passive objects, to be consumed by males as aggressive subjects. o Porn satisfies false needs, rather than promoting truly human relationships in which both males and females are objects and subjects at the same time. Repressive Desublimation and Tolerance: Tolerance fits into this, as the system of repressive desublimation may generate something we may mistake for tolerance: o As society absorbs all the challenges to it, what emerges is ‘a harmonizing pluralism, where the most contradictory works and truths peacefully coexist in indifference’. o Peaceful coexistence sounds like tolerance, but technological progress has produced indifference: o Everyone signs up to economic progress, jobs, some form of capitalism; what does it matter what else they think? o This is not tolerance, but the inability to take seriously critical challenges to society. Perhaps our society is not genuinely tolerant, but an imitation, a fake. o A genuinely tolerant society – one in which autonomy is encouraged, real difference can flourish, many lifestyles are genuinely possible – will not create false needs and repressive desublimation. (6) PARADOXES AND CONTRADICTIONS WITH TOLERANCE ITSELF CONTRADICTIONS WITHIN THE CONCEPT By considering someone as being a ‘tolerant individual’ through Forst’s concept of toleration, we can end up praising a tolerant sexist, racist or homophobe – which seems wrong, as: o their objection can be based in hatred, fear or prejudice o yet they are seen as virtuous even if the higher good of the acceptance component is their own selfinterest (e.g. its better for a racist MP not to act on his racism) o and the rejection component is a minimal action on his part, but only minimal due to vested interest. In other words, it might be necessary to insist that one’s ground or reasons for objection are rational rather than expressions of fear, hatred or prejudice. o The acceptance component is intended to dissolve some of those reasons (e.g. with Ed Dobson he hates homosexuals, but accepts they shouldn’t be persecuted – showing he doesn’t hate homosexuals themselves). o But then we have the paradox of moral tolerance – it seems to be morally right to tolerate what is morally wrong. Note, however, that this only depends on how far one accepts their own beliefs / values to really be moral truths. This is not the case with Barry, Rorty and Mill who take a less absolute approach to one’s own beliefs. THE PARADOX OF WHETHER WE SHOULD TOLERATE THE INTOLERANT The issue with tolerating the intolerant seems paradoxical as if we want to be tolerant we may have to allow views that will lead to the end of tolerance, while if we do not tolerate the intolerant we appear to be intolerant ourselves. WE SHOULD NOT TOLERATE THE INTOLERANT: Karl Popper argues that we should not tolerate the intolerant for two main reasons: 1. An open society of free individuals should be preserved at all times. Even if a tyrant is voted in by a democracy this should not be allowed. o This is not because a benevolent tyrant might not produce better policies, but because it is in an open society that we have the best hope of a social life rationally and humanely organised through listening to and taking account of the views of all. Government should be accountable to the public. o Liberty and tolerance needs protecting against those who would subvert them (i.e. the intolerant) – we do not need to extend freedom or tolerance to those who seek to destroy such values. o He thus avoids what he calls the paradoxes of freedom and tolerance – that unlimited tolerance or freedom allowed to bullies and tyrants will lead to the disappearance of tolerance and freedom for the less powerful. 2. We should not tolerate those who express themselves through violence rather than reason. o When extremism and terrorism are issues, Popper’s insistence to suppress the intolerant in the name of tolerance is extremely important: o ‘[The intolerant] may forbid their followers to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols. […] We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law, and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal.’ WE SHOULD TOLERATE THE INTOLERANT: John Rawls argues that we should tolerate the intolerant as long as they do not express themselves through violence: o If a group puts forward intolerant views, they have no right to complain about people being intolerant towards them. o However, despite this, a tolerant group would be unjust to suppress intolerant views for the same reason: you have to treat other groups according to the practices of your own group – if you are tolerant than you must tolerate them or else equal liberty has been denied. o Unless their own freedom is in danger, tolerant sects have no reason to deny freedom to the intolerant. But, importantly, Rawls qualifies this conclusion by insisting, like Popper, that if the intolerant endanger the tolerant group and its institutions they should not be tolerated: o A tolerant group has the right not to tolerate the intolerant if there are considerable risks to their own legitimate interests. o Each group has a right of self-preservation; justice does not require that men stand idly by while others destroy the basis of their existence, e.g. through violence or by restricting their ability to operate as a group. o This is the only time not tolerating the intolerant is just. NOTE: that the question of tolerating the intolerant encompasses issues such as moral standards in society, conceptions of the good life, religious fundamentalism both within a pluralist society or a society that does not recognise diversity, freedom of expression, fallibility and knowledge.