Moltke EOA Paper - SAMS Comp Prep 13-01

advertisement

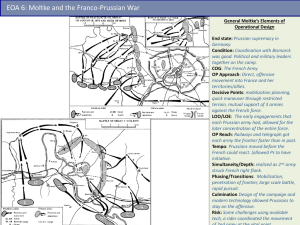

MAJ Knox AMSP 13-01 Seminar 4 EOA Paper – The Franco-Prussian War The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 is one of the most impressive examples of the application of operational art in order to achieve a military solution to a political problem. While friction existed between the views of the Prussian political element under Bismark and the military element under Moltke in terms of the way in which to prosecute the conflict to achieve the overarching strategic objectives, compared to their French adversaries the Prussian politicalmilitary machine was a finely tuned instrument of policy. The conflict, emerging from goals of both French and Prussian political leaders to increase power within continental Europe, resulted in the decisive defeat of the French Army and occupation of large tracts of France by Prussia. Prussia’s military victory facilitated the achievement of the unification of the northern and southern German states into a unified Germany, and set in motion events that would greatly contribute to the catastrophic conflict of the Great War some forty years later. To achieve this strategic endstate, Moltke crafted an in depth operational approach that virtually annihilated the standing French army using maneuver and firepower, while ensuring the force was logistically supportable. Many of the concepts within Moltke’s plan and execution exemplify the basic tenets modern military’s use today, and are key examples of operational art employed to achieve national and strategic objectives. The Prussian political strategic objectives for the Franco-Prussian war all stem from one overarching goal, that of the unification of the northern and southern German states.1 The consolidation of the northern states, annexed by Prussian after the stunning Prussian victory in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, was a shock to the French leadership, and Napoleon III determined that the southern states must not be allowed to follow suit and create a powerful German state 1 Wawro, Geoffrey, The Franco-Prussian War: The German Conquest of France in 1870-1871, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2003, 22. capable of countering French political and military dominance on the continent.2 In order to facilitate the union between north and south Germany, Prussian leaders determined that French power and influence must be diminished to prevent interference with Bismark’s goal of a unified Germany. Militarily, Prussian strategic objectives during the conflict focused on the destruction of the French Army. Moltke, in classic Clauswitzian form, saw the means to achieve victory as the destruction of the enemy’s fighting forces, which in turn allowed the occupation of France and the enforcement of favorable peace terms.3 This focus on military forces is seen throughout the campaign, beginning with the encirclement of Metz, defeat of the French at Sedan, the siege of Paris, and subsequent military operations against French forces in the Orleans region. Both Moltke’s and Bismark’s goals were the same, to defeat France and impose favorable terms for Prussia to set conditions for the unification of Germany. However, Moltke’s focus on the destruction of French military capability often came in conflict with Bismark’s push for the capitulation of the government. This diametrically opposed viewpoint is blatantly visible in the disagreement on the taking of Paris, where Bismark urged for the capture of the city, and Moltke opted for a siege and continued maneuver warfare against the remnants of the French army to the south. Moltke crafted a detailed plan of attack that focused the military objective of the force as the destruction of French forces, which would enable the political objective of the unification of Germany without French interference. His operational approach utilized a direct approach and entailed a rapid mobilization of forces to attack France with three Prussian armies using maneuver to outflank and encircle French armies. Once French elements were encircled, a Prussian force would maintain the siege of these elements while the remainder of the Prussian army would continue the attack in order to maintain the initiative and overwhelm French 2 Ibid., 17. Clausewitz, Carl von. On War. Edited and Translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976, 91. 3 2 capability to defeat the Prussian attack. The operation consisted of four phases. Phase I consisted of the mobilization and movement of military forces and logistical supplies via an expansive rail network with multiple lines converging on the front. Phase II was a rapid attack to defeat the forward French Army of the Rheine forces in vicinity of the Saar River and the pursuit and encirclement of the French army in northeastern France at Metz. Phase III encompassed the defeat of the French Army of Chalons and the occupation of northern France. Phase IV included the isolation of Paris, area security for occupied areas of Northern France, and destruction of remnants of resistance in central France until the French conceded defeat and accepted terms, which would set conditions for the unification of Germany. Moltke’s problem statement was how to employ his three Prussian armies to defeat and initially equivalently sized the French army under Napolean in order to prevent French interference with the political unification of the northern and southern German states. Moltke had at his disposal an exceptionally well trained active army component of 300,000 with an equally well trained reserve force for a total of over one million troops and a distinctive advantage in artillery systems in both quantity and quality, against an French force of initially around 400,000 poorly trained troops who lacked morale and effective artillery support but with far superior rifles. The opportunity provided by the decisive defeat of France enabled the unification of Germany and placed it as the predominant power in Europe, where the risk of failure would unhinge the unification plan and reinvigorate the declining French power on the continent. Considering the objectives established for the conflict, Moltke developed a solution focused on rapid advances to maintain initiative and force the French to piecemeal forces into battle, preventing France’s ability to utilize localized massing of forces to defeat the Prussian advance. Phase I operations included the rapid mobilization of Prussian forces that took advantage of years of planning and an excellent rail system with five main lines running to the theater to 3 rapidly mass three field armies along the border.4 After turning back the half hearted French advance on Sarrbrucken, Moltke deftly orchestrated a counteroffensive that shattered the poorly organized French armies. This seamless transition to Phase II operations seized and exploited the initiative largely due to the long preparation for the conflict by Prussia. Moving to rapidly envelop the massed French elements in Metz culminating with the Battle of Gravelotte that forced French retreat into the city, and aided by the inability of French leaders such as Bazaine to maneuver elements to prevent the encirclement, Moltke isolated the best elements of the French army and facilitated a further push towards Paris.5 With Metz isolated, Moltke established a siege force and turned his remaining units for a continued push westward to counter the French force moving forward from Chalons. Moltke saw Phase III as the most decisive of the entire war. His enemy focused approach concentrated his actions on finding and defeating the French military, and his defeat of the Army of Chalons is an ideal example of the application of operational art to achieve his objective. After engagements with lead French elements at Beaumont, Moltke maneuvered two armies to isolate the massed forces of MacMahon near Sedan. Employing far superior firepower through massed artillery at key points and mobile infantry units defeating any breakout attempts, Moltke encircled the Army of Chalons forced it to surrender.6 Given no option or opportunity to escape, Napolean III and 100,000 French soldiers became prisoners and the French position as the premier world power was shattered.7 Where Moltke saw Phase III as decisive, the capture of Napolean III and the revolt in Paris pushed Bismark to identify Phase IV as the critical phase of the operation. With Napolean III deposed and a new government in place that refused to capitulate, Bismark saw Paris as the 4 Wawro, 80. Ibid., 187. 6 Ibid., 226. 7 Ibid., 229. 5 4 hub of French power and the true objective to prevent French interference with German unification. This difference of opinion would cause consternation between the two Prussian leaders in the ensuing operations during Phase IV. As the Prussians closed on Paris, Moltke was presented with the issue of having to seize a heavily defended and fortified location with nearly double the number of troops than he had to attack it. He opted to isolate the city, preventing either a breakout of the defenders or a break in of relief forces, and established siege lines that would control and prevent access to the city. With Paris invested but the Repulican French government refusing to capitulate, Moltke dispatched a reinforced Corps under General Tann, and subsequently General Mecklenburg, to deal with the relief armies forming south of Paris in the Orleans area.8 This force clashed with French elements south of Paris for months in savage fighting throughout the French countryside as the Prussians attempted to impose order and secure territory. Finally, after months of desperate fighting and Paris nearly starved, the French accepted Bismark’s harsh terms for the end of the war. In addition to paying reparations of nearly 5 billion Francs, France ceded the Alsace-Lorraine area to Prussia. This victory secured the nonintervention of France in the unification of Germany, which changed the balance of power in Europe and established Germany as the leading power on the continent. Moltke’s operations fit within any of the three main operational frameworks, but are best suited in terms of flexibility and exploitation of the initiative within the Main Effort (ME) and Supporting Effort (SE) framework. Throughout the Franco-Prussian War, Moltke displayed his tendency towards rapid shifts in his main effort to achieve the most in terms of attaining his military objective, the defeat of the French Army. Initially Motlke’s main effort focused on the defeat of the Army of Metz with 1st and 2nd Armies up to the Battle of Gravelotte.9 Once this defeat of the French was achieved, 1st and 2nd Armies shifted to a supporting effort as the siege 8 9 Ibid., 256. Ibid., 169. 5 force surrounding Metz, and the Prussian 3rd Army and the Prussian Army of the Meuse shifted to the main effort as they maneuvered forward to engage the advancing French Army of Chalons.10 After the defeat of the French at Sedan and the encirclement of Paris, the 3rd and Army of the Meuse became supporting efforts as Moltke shifted effort once again to defeating newly forming French units south of Paris near Orleans, placing the main effort on elements such as Tann’s and Mecklenburg’s army sections while the remainder of the Army maintained siege operations against the remaining French positions. Through his continual shifting of focus and main effort to adjust to the current situation, Moltke was able to maneuver his forces into positions of advantage over his French adversaries and exploit weaknesses through initiative and understanding of battlefield conditions. Moltke’s operational execution is a prime example of the United States Army’s Tenets of Unified Land Operations (ULO). The Tenets of ULO include Flexibility, Integration, Lethality, Adaptability, Depth, and Synchronization.11 During his operations against the French, Moltke employed each of these concepts within both his planned and subsequent pursuit operations. The most dominant of the tenets of ULO observed within Moltke’s direction of operations are flexibility and adaptability. Moltke never failed to exploit an opportunity to shift and adjust his plan to counter French movements or weaknesses. His ability to shift planning and main efforts daily while on the move afforded the Prussians with the capability of overwhelming French elements with massed combat power. Within the elements of Operational Art, Moltke’s plan relied heavily on his understanding of the French Center of Gravity (COG), Tempo, and Decisive Points. These elements were key to Moltke’s understanding of the conflict and how to achieve victory. Moltke saw the French COG as the French Army, and it remained the focus of his military operations within France. Each time he defeated one element of the French Army, 10 11 Ibid., 211. Headquarters, Department of the Army. ADP 3-0: Unified Land Operations (October 2011), 7. 6 Moltke would press forward to engage the next force. Often at odds with Bismark, who saw the French COG as Paris and the civilian government, Moltke’s focus on the COG as the French Army drove his operations and is exemplified with his efforts in the Orleans area after the encirclement of Paris. With Bismark pushing to seize Paris after the French refused to surrender and seek peace, Moltke decided to maintain the siege of the city instead of assaulting Paris directly and focused military efforts at defeating the relief armies forming in vicinity of Orleans. By defeating these final elements of the French Army that were not already surrounded by his forces, Moltke saw the conflict as complete and only a matter of time before French capitulation. The tempo established by Moltke outpaced the sluggish and ill prepared French forces. Able to shift corps and armies from day to day to apply them at the most advantageous positions, Moltke created a tempo of operations and uncertainty that the French could not recover from. This pace of operations across the breadth of the battlefield led directly to the defeat of both the Army of Metz and the Army of Chalons early in the war. Moltke viewed the isolation and/or destruction of major French armies as decisive points. This was the major focus of his operations throughout the campaign, and he exerted much of his planning effort in isolating these units to allow his army to maintain maneuverability while fixing French elements. Once fixed, these French forces could either be besieged as in the case of Metz and Paris, or destroyed outright and forced to surrender like the Army of Chalons at Sedan. Moltke planned and executed an effective campaign that directly attacked what he saw as the hub of French power, its army. This attack on the French COG was to achieve his strategic objectives of defeating the French in order to prevent their interference in the unification of northern and southern German states. His ability to shift his main effort, seize the initiative, and exploit his adversary’s weakness through his dynamic and flexible management of the battle overwhelmed the ill prepared French army and sealed France’s fate. Despite some issues between himself and Bismark in terms of the ways and means to achieve his strategic objectives of French 7 capitalization, Moltke effectively employed the Prussian military to achieve the strategic end state and unify Germany. 8