Chapter 27 Overview

advertisement

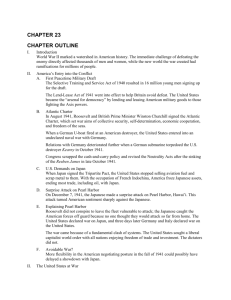

CHAPTER 27 War and Peace CHAPTER OVERVIEW The Road to Pearl Harbor. Relations between Japan and the United States deteriorated after Japan resumed its war against China in 1937. Neither the United States nor Japan desired war. Roosevelt considered Nazi Germany to be a more dangerous enemy and dreaded the prospect of a two-front war. In the spring of 1941, Secretary of State Cordell Hull demanded that Japan withdraw from China. Even moderates in Japan did not accept Hull’s demand for total withdrawal. In July 1941, the United States retaliated against Japan’s occupation of Indochina by freezing Japanese assets in America and placing an embargo on petroleum. Militarists assumed control of Japan’s government, and while the pretense of negotiation continued, Japan prepared to implement war plans against the United States. On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Congress declared war on Japan the following day, and on December 11, the Axis powers declared war on the United States. Mobilizing the Home Front. Congress granted wide emergency powers to the president. However, Democratic majorities were slim in both houses, and a coalition of conservatives from both parties limited Roosevelt’s freedom to act through fiscal oversight. Roosevelt was an inspiring wartime leader but a poor administrator. Nevertheless, Roosevelt’s basic decisions made sense. They included financing the war through taxes, basing taxation on ability to pay, rationing scarce resources and consumer goods, and regulating wages and prices. A lack of centralized authority impeded mobilization, but production expanded dramatically. Manufacturing nearly doubled; agricultural output rose 22 percent. Unemployment virtually disappeared. Productive capacity and per capita output increased especially dramatically in the South. The War Economy. Roosevelt selected James F. Byrnes as his wartime “economic czar.” Byrnes headed the Office of War Mobilization, which controlled production, consumption, priorities, and prices. The National War Labor Board arbitrated disputes and stabilized wages. Despite rationing and wage regulations, American civilians experienced no real hardships during the war. Prosperity and stiffer government controls strengthened organized labor; the war did more to institutionalize collective bargaining than the New Deal had done. The war also effected a redistribution of wealth in America. The wealthiest 1 percent of the population received 13.4 percent of the national income in 1935; by 1944, this group received 6.7 percent. The income tax was extended until nearly all Americans paid. Congress adopted the payroll-deduction system to ensure its collection. War and Social Change. Americans became more mobile. Not only were those in the military moved to training camps all over the United States and to Europe and the Pacific, but wartime industries drew millions of civilians to new areas. Wartime prosperity allowed new marriages and a higher birthrate. Minorities in Time of War: Blacks, Hispanics, and Indians. Several factors improved the condition of black Americans. Hitler’s racial doctrines made racism less respectable. Black leaders pointed out the inconsistency between fighting for democracy abroad and ignoring it at home. Blacks serving in the military were treated more fairly than in World War I; however, the armed forces remained segregated. Economic realities worked to the advantage of black civilians. Unemployment had affected blacks disproportionately; the labor shortage brought full employment. Moreover, defense jobs often involved opportunities to develop valuable skills, opportunities that racist policies of unions and employers had denied to blacks before the war. Blacks moved to the cities of the North, Midwest, and West Coast. Although most migrants had to live in urban ghettos, their very concentration (and the fact that blacks outside the South could vote) gave them greater political clout. The NAACP grew in membership and influence; it also assumed a more activist role. To head off a threatened march on Washington, the president agreed to issue an order prohibiting discrimination in plants with defense contracts. Racial tensions resulted in race riots, the worst of which took place in Detroit. Increased demands for labor led to a reversal of the government’s policy of forcing Mexicans out of the Southwest. In Los Angeles, prejudice against Hispanics erupted into rioting against young men wearing zoot suits. Military service and mobility in search of employment increased the American Indian’s assimilation into white society. The Treatment of German and Italian Americans. World War II produced less intolerance and repression than World War I. In marked contrast to the First World War, Americans in World War II were generally able to distinguish between the enemy in Italy and Germany and ItalianAmericans and German-Americans. Few Italian-Americans supported Mussolini, and most German-Americans were vehemently anti-fascist. Moreover, both groups were well organized and prepared to use their political influence. Internment of the Japanese. In marked contrast to the treatment of Americans of Italian or German descent, 112,000 Japanese-Americans, many of them native-born citizens, were relocated into internment camps. The government feared their potential disloyalty, and the public was aroused by racial prejudice and the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The Supreme Court upheld restrictions on Japanese-Americans in Hirabayashi v. U.S. (1943). Finally, in Ex Parte Endo (1944), the Supreme Court forbade the internment of loyal Japanese-American citizens. Women’s Contribution to the War Effort. Millions of women entered the work force during the war, and more married women than ever worked outside of the home. Despite initial reluctance by employers and unions, women made inroads into traditionally male domains. Black women bore a double burden of race and gender, but the demand for labor created opportunities for them. In addition to prejudice in the workplace, working women faced housework as well. The war also affected women who did not take jobs. Wartime mobility caused problems for the women who faced new, sometimes difficult, surroundings without traditional support networks. War brides often followed their husbands to training camps, where they faced problems comparable to those of women who moved to work in defense industries; in addition, they faced the fear and emotional uncertainties of newlyweds, compounded by separation from husbands who were risking their lives overseas. Allied Strategy: Europe First. Allied strategists decided to concentrate on the European war first. The Japanese threat was remote, but Hitler threatened to knock the Soviet Union out of the war. The United States and Soviet Union wanted to establish a second front in France as soon as possible. Churchill pressed instead for strategic bombing raids on German cities and an invasion of German-held North Africa. Churchill got his way. In 1942, Allied planes began to bomb German cities, and an Allied force under Dwight Eisenhower invaded North Africa. The decision to offer conditional surrender terms to the French collaborationist, Admiral Jean Darlan, enabled Eisenhower to press forward quickly against the Germans after encountering only light resistance from the Vichy French forces. Rommel’s Afrika Korps surrendered in May, 1943. By the fall of 1943, the Soviets had checked the Nazi advance at Stalingrad, and the Allies were pushing their way up the Italian peninsula. Germany Overwhelmed. On D-Day, June 6, 1944, the Allied forces launched a massive attack on the Normandy coast. In the East, millions of Soviet troops slowly pushed back the Axis lines. While Eisenhower prepared for a general advance, the Germans launched a counterattack. The Allies turned back the Germans at the Battle of the Bulge, which cost the Germans their last reserves. On May 8, 1945, Nazi Germany unconditionally surrendered. As the Allies advanced, the horror of the Nazi death camps unfolded. News of the camps had reached the United States much earlier. Yet Roosevelt declined to take any action to save refugees or even to bomb the camps or the rail lines leading to the camps. The Naval War in the Pacific. While the first priority was to defeat Germany, American forces in the Pacific fought to prevent further Japanese expansion. In spite of heavy losses, the American navy turned back a Japanese convoy at the Battle of the Coral Sea (1942). At Midway, the United States fleet decisively defeated a Japanese armada. Thereafter, the initiative in the Pacific shifted to the Americans. Island Hopping. American forces ejected the Japanese from the Solomon Islands in a series of battles around Guadalcanal in which American air power proved decisive. American forces advanced steadily, and by mid-1944, American land-based bombers were within range of Tokyo. In February 1945, MacArthur liberated the Philippines. Two battles in Philippine waters (1944) completed the destruction of Japan’s sea power and reduced its air power to kamikazes. American forces took Iwo Jima and Okinawa, only a few hundred miles from the Japanese mainland, in March, 1945. The tenacity of Japanese soldiers made it seem that the actual invasion and conquest of Japan would take at least another year and cost an additional million American casualties. Building the Atom Bomb. Following Roosevelt’s death in April, 1945, Harry S. Truman became America’s president. America’s scientific community delivered a powerful new weapon, the atom bomb, to Truman. The United States had devoted over six years and $2 billion to develop this weapon. After the first successful test on July 16, 1945, Truman faced a difficult decision. He could authorize bombing the Japanese cities with this weapon, or he could finish the war using conventional means. The motives behind Truman’s decision are still debated. On August 6 and 9, 1945, atomic weapons devastated the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Truman’s decision was influenced by the potential casualties involved in an invasion of Japan, as well as a desire to end the war before the Soviet Union could intervene effectively and claim a role in making peace. Hatred of Japan undoubtedly also influenced the decision. On August 15, Japan surrendered unconditionally, and the Second World War ended. Millions of people perished in the war, and many areas lay in ruins. Despite the war’s horrible cost, improvements in technology and medicine held out the promise of a better world. Scientists argued that the power of the atom could also serve peaceful needs. With the drafting of the United Nations charter in 1945, the world hoped for international cooperation. Wartime Diplomacy. Hopes of world peace and harmony failed to materialize, largely because of a split between the Soviet Union and the western allies. During the war, American propaganda spared no effort to persuade Americans that the Soviet Union was a devoted, peace-loving ally. Joseph Stalin was portrayed as a kindly father figure. Such views were naive at best, but the war created an identity of interest in defeating a common enemy. Moreover, the Soviets expressed a willingness to cooperate in resolving postwar problems, and the Soviet Union was one of the original signers of the Declaration of the United Nations. In May, 1943, the Soviets dissolved the Comintern. In October, the “Big Three” powers established the European Advisory Commission to set policy for the occupation of Germany. The Big Three met and cooperated constructively at Teheran and Yalta. At San Francisco, the Allies created a United Nations Organization consisting of a General Assembly (made up of all member nations) and a Security Council (consisting of five permanent members and six other, temporary members). Allied Suspicion of Stalin. Long before the war ended, the Allies clashed over important issues. Stalin deeply resented the delay in opening a second front. At the same time, the Soviet leader never concealed his determination to protect his western frontier by exerting control over Eastern Europe. Most Allied leaders conceded Stalin’s dominance in Eastern Europe, but they never publicly acknowledged this. Conflicts between western commitments to self-determination and Soviet desires for security presented difficult problems, particularly in Poland. Yalta and Potsdam. At Yalta, Roosevelt and Churchill agreed to Soviet annexation of large sections of eastern Poland. Stalin agreed to allow the Poles to hold free elections, a commitment he probably never intended to keep. A pro-Soviet regime was installed in Poland. The new president, Truman, met with Stalin and the British leadership at Potsdam in July, 1945. Potsdam formalized the occupation of Germany. Fortified by news of the successful testing of an atomic bomb, Truman made no concessions to the Soviets. Stalin refused to relinquish his hold on Eastern Europe. Suspicions mounted and positions hardened on both sides. The end of World War II marked the beginning of a new international order dominated by the Soviet-American rivalry. LEARNING OBJECTIVE QUESTIONS 1. What events led to the war with Japan? 2. How did World War II affect the American economy? 3. In what ways did World War II affect ethnic and racial minorities? 4. Why were Japanese-Americans interned? 5. What changes did women experience during the war? 6. Why did the Allies decide to concentrate on the defeat of Germany first? 7. What was the American strategy in the Pacific? 8. Discuss the controversy surrounding Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb. 9. What points of conflict emerged between the United States and the Soviet Union?