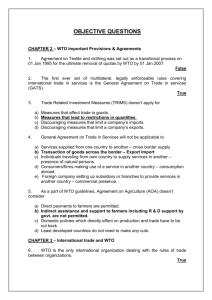

Content - Department of Geography

advertisement