ESL - Partner and Grouping Strategies

advertisement

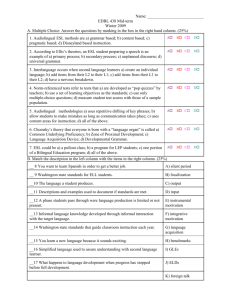

CASSL Project: ESL Student Partner and Grouping Strategies Class: ESL L 40 Instructor: James Wilson (1) Project Goal: Statement of the problem or issue studied and its importance at CRC. Issue: Students in college-level ESL courses come to classrooms with a wide variety of backgrounds and skills. One aspect of instructor pedagogy is to assist them in their acculturation to American college/university classroom expectations, values, and behaviors. Many are successful in their quest for English and, further, a U.S. college education; however, some meet barriers having more to do with cultural insularity than their ability to learn English. In the context of credit ESL classes, some come with friends and/or family members who speak their native language, and in classes where 9, 10, 12, etc. countries may be represented, they remain in L1 cultural/linguistic enclaves where translation can be the norm. This, essentially, wastes their given opportunity to practice English with those outside their culture, lessens the likelihood of cross-cultural learning that often takes placed in multicultural classes, and often makes the challenging road to English fluency and college success more difficult than it already is. The grantee would initially pair all students up, as much as is possible, with a class partner who is from a different L1 (1st language) and, as the semester continues, pair these groups with others so that more cross-cultural (and thus, L2 – 2nd language – interaction occurs). This could occur after a student-interest survely is conducted week 1, pairing up those who have similar, or compatible, interests. A mid-term meet-andgreet could be arranged to check on student attitudes toward the strategy. Methods: Outline of the tools used to study the problem and the analyses conducted. This grant project is based on the following: 1) Research of existing data related to student pairing/grouping strategies, 2) Student entry and exist questionnaires related to attitudes working with others and cultural values clarification, in addition to class satisfaction surveys, 3) Faculty reflection on the impact and success of partner/grouping strategies, 4) Comparison of the focus group with same-level classes over a 3-5 year period (grades, class completion, etc.). As the semester continued, COMPASS?CELSA student surveys also provided pertinent information for this research. (3) Results Summary: Overview of what was learned. COMPASS/CELSA Validation research conducted by the CRC Basic Skills Committee provided useful data for this mini-grant project. In this ESL L 40 class, where the emphasis is on developing student listening/speaking skills, nine (9) of thirty (30) students who responded to the survey stated that the class was too difficult for them. Of those nine students, eight (8) are Chinese. Chinese students, typically, are among the most insular and least comfortable working outside their first language and culture. In this class, they would be among those I would have most wanted to break up at (2) the beginning of the class in order to promote multicultural learning and English language use in the classroom. My course syllabus makes my attitude clear; however, such students still, left to their own devices, will sit next to those who speak their 1st language and are those most likely to break into 1st language discussion during classroom discussions intended to promote English language use. Although this is not enough data to make large conclusions, it does support the need to raise student awareness regarding how such classroom behaviors can negatively impact language acquisition, and possibly, reinforce the notion that mandatory student grouping is necessary in the context of intermediate and higher ESL courses. My own classroom behavior student survey forced students to look at their classroom behavior and attitudes. The first question posed was this: How do you feel working with people from different cultures? Of 28 students surveyed, 17 expressed generally positive attitudes toward working outside their first language and culture, and 11 expressed generally negative feelings, ranging from “stressed” to one student who thought I should not be asking such a private question. Further, nineteen (19) students stated they regularly sit next to someone who speaks his or her 1st language in class. Part of this can be due to the large number of students from China and Vietnam, but it can also speak to the idea that there is a significant number of students who sit next to those who will reinforce habits that can slow them down in the context of second language acquisition. Simply, it makes them feel comfortable. Comfort, of course, is a good thing, but placed into the context of learning a new language, practicing a new language, and respecting the diverse nature of Sacramento’s classrooms, it should be secondary from a learning standpoint. I will admit to never having a seating chart in any of my ESL classes and trying it for the first time here this semester. It produced some student discomfort to be sure. Students were initially grouped in fours according to their responses about sitting next to those who speak their first language. That is, two (2) students who responded positively were matched with two (2) who replied negatively. Needless to say, there were some who were truly uncomfortable sitting next to someone from a different language and culture. There were some who merely sat during discussion or read as they did not see this as an opportunity. I learned that the seating chart idea had to be repeated at the beginning of each class where I wanted to use it as, without the reminder, students in this class would revert back to the old habits immediately. (4) Planned Implementation: List of changes you have planned for your program or courses based on what you learned. Create a class seating chart for L 40 Listening, keeping in mind the multicultural nature of our classes. This one had students from nine (9) different. Hand out a student list of expected classroom behaviors conducive to language learning CRC student demographic data in class syllabus Share U.S. Census Bureau data related to Sacramento in class syllabus or 1st week handouts Continued 1st week student surveys related to working outside 1st language/culture Show multicultural class video on cultural similarities/differences week 1 Give general information on U.S. culture groups week 1 Give U.S. Census Department data on population demographics in Sacramento and California in order to promote thought and student discussion on diversity from the beginning of the class. Make explicit teacher recommendations about English language use for class work and working with students from a variety of cultures in the class syllabus. (5) Broader implications: Overview of the implications of your results for the larger college community. Students from a wide variety of language and culture groups will continue to come to Cosumnes River College. Student classroom expectations and behaviors may sometimes differ. As one example, an Accounting professor mentioned to me that there is a large number of “Asian” students who wish to pass a state test and work for the state of California. However, he stated that many do not reach the language level to do that by attempting the class and test before ready and that their need to work together with others from the same language/culture holds them back. For me, having a classroom where everyone knows English is the language of communication is one conducive to language acquisition. It is absolutely necessary at the intermediate level and beyond if students are to develop the skills necessary to succeed in an academic and work context. Having an ESL class where students are talking away in their 1st languages is not an effective learning environment. As instructors, we are not responsible for enabling student classroom behaviors that clash with expectations of American college classrooms and current second language acquisition research and theory. More classroom-based research is necessary, and I will continue to do this. I will share what I have learned with my ESL colleagues at CRC and, as time continues, present at a state CATESOL conference on the issue to share with a broader audience. Appendix - CASSL Student Grouping Bibliography Chamot, A.U., & Stewner-Manzanares, G. (1985). Review, summary, and synthesis of literature on English as a second language. McLean: InterAmerica Research Associates. 2. Crandall, J. (1992). Content-centered learning in the United States. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 13, 111-126.. 3. Cross,D. 1992. A Practical Handbook of Language Teaching. London: Prentice Hall Int. Ltd. 4. Echevarria, J., & Graves, A. (1998). Sheltered content instruction: Teaching English language learners with diverse abilities. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. 5. Freiberg, H. J. & Driscoll, A. 1992. Universal Teaching Strategies. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon. 6. Lucas, T., Henze, R., and Donato, R. (1990).Promoting the success of Latino language-minority students: An exploratory study of six high schools. Harvard Educational Review, 60 (3), 315340. 7. Short, D. J. (Fall, 1991). Integrating language and content instruction: Strategies and techniques (NCBE Program Information Series, Number 7). Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education. 8. Sidin, R. 1993. Classroom Management. Kuala Lumpur: Fajar Bakti Sdn. Bhd 9. Underwood, M. 1987. Effective Class Management. England: Longman Group Ltd. 10. Simich-Dudgeon, C., McCreedy, L., & Schleppegrell, M. (Winter 1988/89). Helping limited English proficient children communicate in the classroom: A handbook for teachers. National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education. Program Information Guide Series, No. 9. 11. Matthews-Aiydini and Van Horne, Regina (April 2006). Promoting the Success of Multilevel ESL Classes: What Teachers and Administrators Can Do. Center for Adult English Language Acquisition (CAELA) 12. Weber, W. A. 1994. Classroom Management. In J. M. Cooper (ed). Classroom Teaching Skills, Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath and Co. pp. 234-269 1.