Georgia v Randolph

advertisement

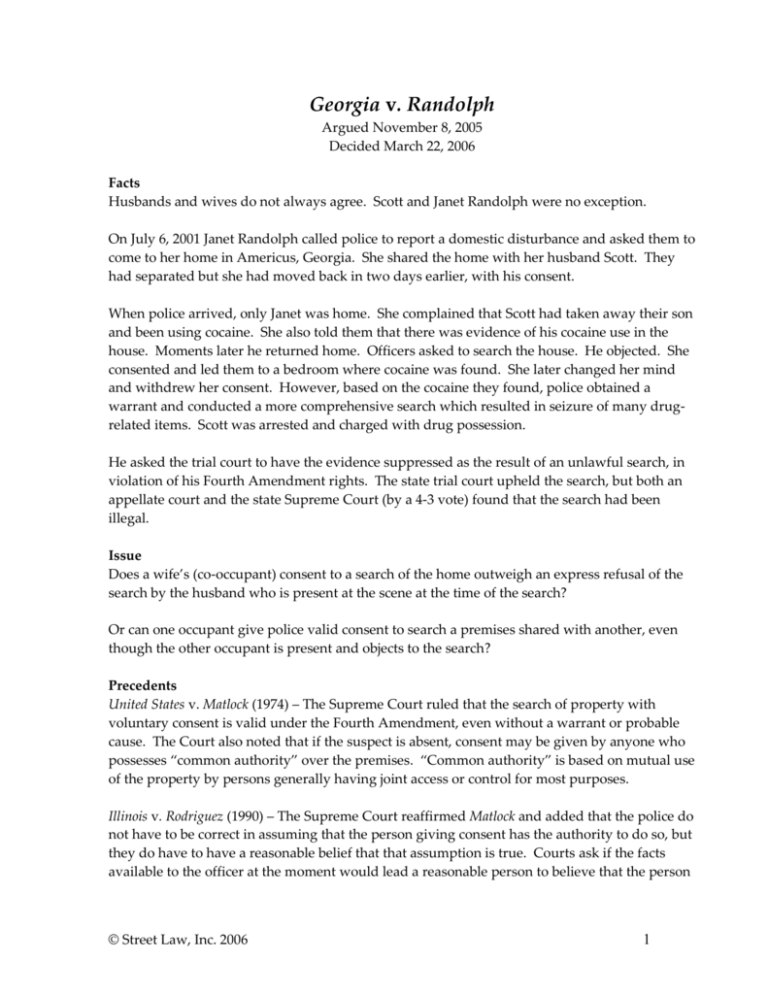

Georgia v. Randolph Argued November 8, 2005 Decided March 22, 2006 Facts Husbands and wives do not always agree. Scott and Janet Randolph were no exception. On July 6, 2001 Janet Randolph called police to report a domestic disturbance and asked them to come to her home in Americus, Georgia. She shared the home with her husband Scott. They had separated but she had moved back in two days earlier, with his consent. When police arrived, only Janet was home. She complained that Scott had taken away their son and been using cocaine. She also told them that there was evidence of his cocaine use in the house. Moments later he returned home. Officers asked to search the house. He objected. She consented and led them to a bedroom where cocaine was found. She later changed her mind and withdrew her consent. However, based on the cocaine they found, police obtained a warrant and conducted a more comprehensive search which resulted in seizure of many drugrelated items. Scott was arrested and charged with drug possession. He asked the trial court to have the evidence suppressed as the result of an unlawful search, in violation of his Fourth Amendment rights. The state trial court upheld the search, but both an appellate court and the state Supreme Court (by a 4-3 vote) found that the search had been illegal. Issue Does a wife’s (co-occupant) consent to a search of the home outweigh an express refusal of the search by the husband who is present at the scene at the time of the search? Or can one occupant give police valid consent to search a premises shared with another, even though the other occupant is present and objects to the search? Precedents United States v. Matlock (1974) – The Supreme Court ruled that the search of property with voluntary consent is valid under the Fourth Amendment, even without a warrant or probable cause. The Court also noted that if the suspect is absent, consent may be given by anyone who possesses “common authority” over the premises. “Common authority” is based on mutual use of the property by persons generally having joint access or control for most purposes. Illinois v. Rodriguez (1990) – The Supreme Court reaffirmed Matlock and added that the police do not have to be correct in assuming that the person giving consent has the authority to do so, but they do have to have a reasonable belief that that assumption is true. Courts ask if the facts available to the officer at the moment would lead a reasonable person to believe that the person © Street Law, Inc. 2006 1 consenting actually lived at the residence and thus had authority over it. If so, the search is valid. Minnesota v. Olson (1990) – The Supreme Court held that an overnight house guest has a reasonable expectation of privacy and can claim protections of the Fourth Amendment. Even though the guest does not live there, the Fourth Amendment protects him from unreasonable government intrusion into that place. This means that the actual occupants of the residence cannot give police consent to search the guest’s belongings if the guest objects. The guest has a right to refuse consent to the search. Arguments for Randolph US v. Matlock is a case in which the consent of a common authority was valid because the other co-occupant was not present and therefore did not object to the search. In this case, Randolph was present and expressly objected to the search. The Court has only approved searches on the basis of third party consent when the individual has waived his right to refuse the search. In this case, Randolph has not done that. In fact, he exercised his right to refuse the search and thus his wife’s consent is not enough to allow the search. An occupant who makes an outright objection to a search is asserting his right to privacy and making it clear to officers that he has not given up control of the premises to another person. Randolph’s wife cannot waive his right to privacy if he expressly asserts it. Allowing one occupant to override the objections of another would be an extraordinary intrusion into personal privacy, which the Fourth Amendment expressly prohibits. The home represents the most important zone of personal privacy protected by the Fourth Amendment. The fact that the home is shared with another should not limit one’s expectation of privacy. The police could have used what the wife told them to get a warrant. The goal of protecting society from criminals could still be met without invading Randolph’s privacy. Arguments for the State of Georgia A person who has “common authority” over a shared premise should be able to give consent for a search of that premise in his or her own right, if that permission is given voluntarily. Sharing a house comes along with a reduced expectation of privacy, and therefore consent to search by one occupant does not infringe on another occupant’s reasonable expectation of privacy, even in the face of that other occupant’s refusal to consent. © Street Law, Inc. 2006 2 It was totally reasonable for the police to believe that Randolph’s wife was a co-occupant who had common authority over the house and thus the power to consent to the search. Randolph’s wife did not waive Randolph’s rights, but rather exercised her own right to allow the search of her home. Co-occupants assume the risk that another occupant might permit a search. Just as Mrs. Randolph could bring the evidence outside to the police, she could also let the police go into the house and search it. It is her home, too. If police are not allowed to enter a house based on one person’s consent over another person’s objection, they will not be able to protect domestic violence victims. Obviously in a domestic violence situation, the victim would want to police to come in, while the abuser would object. If you take the abuser’s objection over the victim’s consent, then the victim is left at risk of further violence. Decision Justice Souter wrote the opinion of the court, which Justices Stevens, Kennedy, Ginsburg and Breyer joined. Justices Stevens and Breyer also filed concurring opinions. Chief Justice Roberts wrote a dissenting opinion, which Justice Scalia joined. Justices Scalia and Thomas filed dissenting opinions as well. Justice Alito took no part in the decision. Majority The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Randolph. They held that a physically present cooccupant’s stated refusal to permit a search of the premises renders a warrantless entry and search unreasonable and invalid. The Court reasoned that the Fourth Amendment, which ordinarily prohibits warrantless searches, allows for voluntary consent to search by an individual possessing authority of the premises. Co-occupants share common authority and thus one occupant can give consent when the other is absent. Unlike Matlock however, this case presents a situation where the other occupant is present and expressly refuses the search. The Court relied on Olson and asserted that if overnight house guests have an expectation of privacy, then co-occupants have an even stronger claim of privacy. Additionally, the Court reasoned that there is no superior right to authority among co-tenants, and thus consent by one occupant over the objection of another does not justify a search. In response to the argument that this rule could hinder police protection of domestic violence victims, the Court allows for an exception where the police can enter despite objections by one of the co-occupants if there is fear for the safety of someone inside. Ultimately the Court concludes that a warrantless search of a shared dwelling for evidence over the express refusal of consent by a physically present resident cannot be justified as reasonable on the basis of consent given by another resident. Therefore, the evidence gathered during the illegal search should remain suppressed and cannot be used against Randolph. © Street Law, Inc. 2006 3 Dissent The dissent argued that the consent of Randolph’s wife should be considered valid, because a warrantless search is reasonable if the police obtain the voluntary consent of a person authorized to give it. Co-occupants have assumed the risk that another occupant might permit a search of the residence because they chose to share their home with others. Proof of voluntary consent is not limited to proof that consent was given by the defendant; instead the government need only show that permission was obtained from a third party who possessed common authority over the premises. Shared use of property makes it reasonable to recognize that any of the co-inhabitants has the right to permit the inspection in his own right. Further, the dissent argued that the majority’s rule is arbitrary in that it only protects an occupant who is present to object, and does not extend the protection to absent or sleeping occupants. Additionally, the dissenters argue that the rule threatens the protections afforded to domestic violence victims if police would not be able to enter the home at the request of a victim over the objections of an abuser. Rather than constitutionalize an arbitrary and dangerous rule, the dissent argued, the Court should acknowledge that a decision to share a private place necessarily entails the risk that those with whom we share may in turn choose to share with the police. © Street Law, Inc. 2006 4