Review - WordPress.com

advertisement

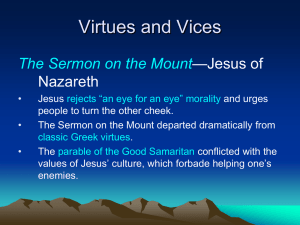

DRAFT ONLY 1-25-10 Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung, Glittering Vices: A New Look at the Seven Deadly Sins and Their Remedies (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2009). Literature on spiritual formation often focuses on its ultimate goal or on the kinds of exercises or disciplines that can help the reader achieve this goal. There is, of course, much wisdom in this approach. And yet it is often ineffective: many careful readers nonetheless fail to begin practicing the relevant disciplines or to make much progress toward taking on the character of Christ. A partial explanation is that, for many of us, there are substantial inner obstacles to a robust and ongoing pursuit of what we know is best and most vital. It stands to reason that the literature on spiritual formation would benefit from a deeper and more probing account of some of these obstacles. Glittering Vices is an excellent and important contribution in precisely this regard. It offers a thoughtful, historically informed, and engaging account of the so-called “seven deadly sins” or “capital vices” — an account in which most readers are bound to catch glimpses of themselves and that can therefore be put to good use in a program of spiritual formation. Konyndyk DeYoung describes this function of her book as follows: One of the movements in the rhythm of discipleship and sanctification is the movement of dying … We come as though to the edge of our own graves and renounce our old self and its habits and practices. Yet that renunciation, as a preface to new life, requires knowing our sin. This is just how the tradition of the seven vices got started. The desert fathers’ classification of seven vices began as a Christian system of self-examination in the fourth century and continued to provide an almost ubiquitous rubric for confession in penitential manuals up until the fifteenth century — an endurance that testifies to their power as a spiritual tool for confession and repentance. When we study the vices, we can better articulate for ourselves what parts of our sinful nature we are grappling with and trying to put to death, and learn how one vice might variously reveal itself in feelings and actions … Naming our sins is the confessional counterpart to counting our blessings. Naming them can enrich and refresh our practices of prayer and confession and our engagement in the spiritual disciplines (21). Glittering Vices begins with an introduction to the notions of virtue and vice and an explanation of why vices in particular are worth reflecting on within the context of Christian spiritual formation. Chapter 1 offers an interesting and illuminating account of the origin and history of the relevant “vices tradition,” which began with the desert fathers in the late fourth century AD. Here Konyndyk DeYoung charts the evolution of the various historical lists of capital vices (they were initially eight in number; and even today there is no single authoritative list) and explains her reasons for preferring the label “capital vices” to the more familiar “deadly sins” (the main reason being that the former term was in use centuries before the latter). Each of the subsequent chapters consists of a focused examination of one of the following seven vices: envy, vainglory, sloth, avarice, anger, gluttony, and lust. The discussion in these chapters draws heavily and fruitfully from various Christian thinkers of the past — particularly Thomas Aquinas — while also exhibiting a familiarity with the contemporary literature on its subject. The author also makes regular and effective use of illustrations from literature, music, and film. Given its accessibility, far-reaching scope, and “glittering” subject matter, Glittering Vices is potentially useful in a very wide range of contexts: from retreats, to small groups, to adult Christian education courses, to undergraduate academic courses in ethics or theology. One overriding idea in Konyndyk DeYoung’s thinking about the capital vices, borrowed from Aquinas, is that they “aim at the things that most attract human beings, the goods which we most long to possess” (38). The suggestion is that there is, in fact, a good or natural impulse at the heart of each of the capital vices. Thus, in her profiles of them, a central strategy is that of disentangling the relevant good concerns or tendencies from certain lethal ones, or of showing how the vice in question represents a distortion or perversion of an otherwise healthy appetite. In staking out positions on these matters, Konyndynk DeYoung takes pains to defend views that are deeply informed by and faithful to the Christian intellectual tradition. This results in some treatments of the capital vices that are likely to surprise many modern readers. For instance, instead of characterizing sloth in terms of a general laziness or propensity toward inactivity, she defines it in such a way that its possession is consistent with the very kind of busyness or work ethic that might be thought to rule it out. In short, she argues, convincingly and again with Aquinas, that sloth is essentially resistance to the demands of love – particularly the love of God (85-89). This, of course, is something to which even the workaholic or busybody might be susceptible (indeed, as the author also suggests, the latter tendencies might be ways of avoiding the duties involved with a proper love of God, neighbor, or spouse). As indicated by the subtitle, another aim of the chapters on individual vices is to identify “remedies” for them. Thus, after profiling each vice, the author proceeds to identify measures for avoiding the vice in question or for rooting it out of one’s character. I confess to finding these discussions somewhat less satisfying – not because of their practical orientation, but rather because of a relative lack of the kind of psychological attentiveness, realism, and sophistication that so enriches the rest of the book. For instance, a suggested antidote to envy is to “practice doing acts of love for others” (56) and a proposed remedy for vainglory is “fasting from advertisements and shopping malls and TV commercials and mail-order catalogs for a period of time” (76). These very well may be effective solutions. The problem is that if I am seriously in the grip of envy or vainglory, I am likely to be unable (or at least unwilling) to avail myself of them. This is, however, a relatively minor criticism, for the more focused and detailed accounts of individual vices and their interconnections are themselves a substantial source of practical guidance. They provide the student of Jesus with a kind of map of the soul, a proper understanding of which is likely to be more illuminating and motivating than any simple behavioral prescription. Overall, Glittering Vices is an impressive example of philosophy undertaken as “soul care.”1 And, unlike many contemporary treatments of its subject matter, it makes good sense of, rather than obfuscates, why the traits in question have traditionally been regarded as posing a mortal threat to human flourishing.2 1 Another fine and very recent example is Gregg Tenelshof’s I Told Me So: Self-Deception and the Christian Life (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2009), also reviewed in the present issue. 2 The series of books on the seven deadly sins published by Oxford University Press between 2003 and 2005 is a good example of a recent treatment of the subject matter that, in many respects, can leave an honest reader wondering how any sane or half-intelligent person could have serious moral concerns about the traits in question. Another recent counterexample to this historically short-sighted (though often engaging and entertaining) approach, undertaken mainly from a secular standpoint, is Gabriele Taylor’s Deadly Vices (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006). Jason Baehr Associate Professor of Philosophy Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles Ph.D. University of Washington, Seattle Areas of specialization: epistemology and virtue theory