What did the Buddha Teach?

advertisement

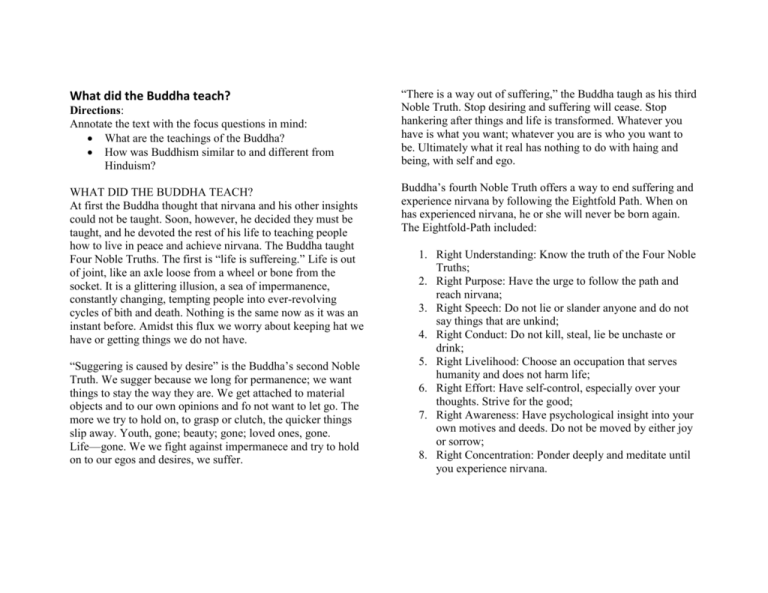

What did the Buddha teach? Directions: Annotate the text with the focus questions in mind: What are the teachings of the Buddha? How was Buddhism similar to and different from Hinduism? WHAT DID THE BUDDHA TEACH? At first the Buddha thought that nirvana and his other insights could not be taught. Soon, however, he decided they must be taught, and he devoted the rest of his life to teaching people how to live in peace and achieve nirvana. The Buddha taught Four Noble Truths. The first is “life is suffereing.” Life is out of joint, like an axle loose from a wheel or bone from the socket. It is a glittering illusion, a sea of impermanence, constantly changing, tempting people into ever-revolving cycles of bith and death. Nothing is the same now as it was an instant before. Amidst this flux we worry about keeping hat we have or getting things we do not have. “Suggering is caused by desire” is the Buddha’s second Noble Truth. We sugger because we long for permanence; we want things to stay the way they are. We get attached to material objects and to our own opinions and fo not want to let go. The more we try to hold on, to grasp or clutch, the quicker things slip away. Youth, gone; beauty; gone; loved ones, gone. Life—gone. We we fight against impermanece and try to hold on to our egos and desires, we suffer. “There is a way out of suffering,” the Buddha taugh as his third Noble Truth. Stop desiring and suffering will cease. Stop hankering after things and life is transformed. Whatever you have is what you want; whatever you are is who you want to be. Ultimately what it real has nothing to do with haing and being, with self and ego. Buddha’s fourth Noble Truth offers a way to end suffering and experience nirvana by following the Eightfold Path. When on has experienced nirvana, he or she will never be born again. The Eightfold-Path included: 1. Right Understanding: Know the truth of the Four Noble Truths; 2. Right Purpose: Have the urge to follow the path and reach nirvana; 3. Right Speech: Do not lie or slander anyone and do not say things that are unkind; 4. Right Conduct: Do not kill, steal, lie be unchaste or drink; 5. Right Livelihood: Choose an occupation that serves humanity and does not harm life; 6. Right Effort: Have self-control, especially over your thoughts. Strive for the good; 7. Right Awareness: Have psychological insight into your own motives and deeds. Do not be moved by either joy or sorrow; 8. Right Concentration: Ponder deeply and meditate until you experience nirvana. THE MIDDLE WAY AND COMPASSION FOR EVERYTHING The Buddha’s teaching offered a Middle Way between the brahmins’ exhaustive rules and rituals and the extreme asceticism of the Jains and others. The Buddha taugh that anyone can have a meaningful existence by following the Middle Way. Eat enough to survive, but do not live to eat. Try to hurt others as little as possible, but recognize that it is impossible to be blameless and hurt nothing. The Buddha also found a middle way between the concerns of life in this world (samsara) and the reality of enlightenment (nirvana). The first five steps of the Eightfold Path deal with life within society and how one can live an ethical life. Steps six, seven, and eight are concered with developing one’s spiritual side and how, through discipline and meditation, one can gain freedom and this wordly existence and experience nirvana. A central concept of Buddha’s life and teaching was karuna or compassion. Compassion for people’s suffering start Buddha on his spiritual quest in the first place. Compassion moved him to teach and informed his instruction to hurt others as little as possible. The Buddha knew that it was impossible to eliminate things that made people suffer, but he helped people change their attitude toward those things. For example, one day a grieving young mother came to Buddha, cradling her dead baby in her arms. “please,” she implored, “you are a holy man. Bring my baby back to life.” The Buddha promised to do so as soon as she brought him a mustard seed from any home where no one had ever died. She was overjoyed to have been asked to perform such a simple task, and she knocked on one door after another. In every household death had come. Resigned she returned to the Buddha to listen to his teachings. People should not rely on the rituals brahmins performed, the Buddha preached, or get involved in intricate philosophical arguments. When asked theological questions, he replied with other questions. “If your friend were hit by an arrow and lay wounded before you,” he said, “would you first try to establish who had made the arrow, the materials used, the direction of its flight, and the speed at its impact? Wouldn’t you first help your friend? My fellow humans are in pain. I strive to minister to their suffering.” And he devoted the last forty years of his life to that ministry. Buddha was a reformer who wanted to correct some of the problems in Indian society, especially that excessive power of the brahmins. He believed in karma, but he thought that if a paersom had not intended to do wrong, then he or she would not build up bad karma. In a radical departure for his time, the Buddha did not believe in gods or goddesses. He taught that everyone could seek enlightenment on his or her own, without the help of brahmins, rituals or deities. Anyone could follow his Eightfold Path and become a Buddha, and he taught in the language spoken by ordinary people, so anyone could understand his teachings. Equally radical was his insistence on complete equality among his followers. “No one is an outcaste by birth,” he said, “nor is anyone a brahmin by birth. It is by deeds that a person becomes a brahmin.” By the end of the Axial Age, people who lived in the Indian sub-continent tended to agree on certain principles and accepted dharma, karma, and samsara as major core ideas. Most believed in a single, ultimate reality often called Brahman, and worshipped one or more of the major gods. Because any effort to explain Brahman fell short, Indian thinkers tended to be tolerant of the various ways people understood it. They also had come ot believe in moksha or nirvana—the possibility of realizing their true nature and not being born again. For the Buddha, blowing out the flame of desire would set a person free. The ultimate goal of both teachers was freedom from samsara. Others looked inward to the deep recesses of the human mind and spirit to find insight into ultimate reality and answers to the perennial questions of meaning, justice, suffering, and evil. In the next act we will consider how as the years go by, their insights would reshape the Indian worldview, influence other cultures, and lead to many changes in how people live their lives. Source: The Human Drama. Johnson-Johnson. Pages 164-167.