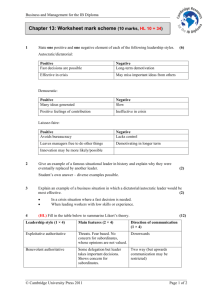

Contingency Approaches to Leadership

advertisement