June 14, 2001

advertisement

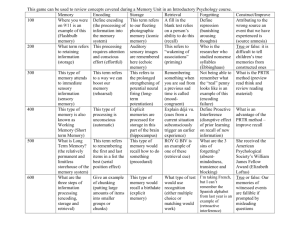

MEMORY DEVELOPMENT Memory concepts Contents: declarative (explicit), subject to conscious recall; implicit (unavailable to conscious recall); or nondeclarative (procedural) Types: semantic memory (language terms); episodic memory (for events or episodes) Recognition is the most basic form of retrievalmerely recognizing a stimulus as new or familiar. Recall is more demanding, as you must remember something without it being perceived. Cued recall means there is a context or cue to the item needed. Cues elicit more information, but they must be effective cues. Free recall means the cue is self-generated. Location memory is memory for spatial locations of items and it develops early, so there are few age differences. Context-independent learning refers to learning rote facts in school education, purportedly for later use or elaboration. Memory development in infancy has been studied with habituation modalities- it shows discrimination as well as retrievable memory. Preference for novelty paradigms show that babies recognize new stimuli and prefer novelty over repeated stimuli. 5 – 6 mo. old babies show visual memory that lasts as long as 2 weeks. Sucking tests show that babies will suck harder to hear familiar rhymes than novel ones- auditory memory. Conditioning techniques- Rovee-Collier showed in the crib-mobile tests that babies as young as 3 mo. remember the kicking activity 8 days. Context in memory recall has been shown to make a difference- in similar conditions babies recall behaviors more accurately. They were even able to recall a 3-part sequence of behaviors over 24 hours. This is essential for learning language. Deferred imitation tasks showed that 10 – 20 mo. old babies could see an act and recall it and use it as long as 1 year later. Implicit memory is memory for information without being aware that one is remembering. This does not show an age difference. An interesting experimental technique used involved wiring up 10 yr.olds to register changes in skin conductance. Then they were shown pictures of 4 and 5 yr. olds, some of whom were classmates several years before. Even though they didn’t show very accurate explicit memories for the childrens’ faces, they often registered internal responses to the familiar children. This indicates that implicit memory may be more related to infant memory, automatic memory than later explicit memory. Remembering events is an explicit memory, as we are aware we are remembering an event we witnessed or learned. We may not have intended to learn something, it just occurred involuntarily- naturalistic learning. Development of event memory requires attention, interpretation, and storage. There can be a glitch in the process at any point. Children often pay attention to very different things than adults do, since they value and are attracted to different things (Cliff in Annapolis). Script-based memory is memory for events according to their sequences of actions (schematic organization.) We develop scripts for things we repeat, so we develop a prototype of expectancy. The 2.5 yr. old telling about the camping trip shows how children remember orders of events, but not specifics of events. Two-year-olds are trying to process much new information and the way they do that is by embedding it into a context/ script that is familiar and repeatable to them. Memory is serving to help children predict events. So repeated events are more predictable than single events. Recurrent events are more important to know and understand and predict. Being able to anticipate an event allows even a baby to participate more fully in their lives. Specific cues can elicit specific memories, but we don’t always know what cue is effective. (Story about 2.5 yr. old Kiesha recalling the bee sting accurately when she sees an ice cube wrapped in a cloth. Her account was more explicit than she could have expressed when the sting happened 6 mo. before.) Role of parents in teaching children to remember- parents play an important role in children’s early memory development, focusing attention on certain things rather than others, conceptualizing related items, describing connections in items and finding different things of interest in what is presented by an experience. It teaches children to observe according to the who, what, where, when, & how of their world. How parents focus attention and describe things teaches children how to focus and remember. Parents offer cues to memory as they ask children what they remember from an experience. Children whose parents will reinforce an encounter by questioning their memories actually keep more accurate memories than children whose parents don’t enhance their remembrances. As parents talk about past experiences, they add to a child’s verbal repertoire as well as autobiographical memory. Parents also talk differently to boys and girls, resulting in girls having a better memory for shared events than boys. Girls are given more evaluative feedback from parents, are encouraged to embellish their stories more elaborately, and to focus more on social interactions (boys are given more feedback about learning). So we learn to talk about and remember what is focused on for us by our parents. Children as eyewitnesses (particularly critical for the legal profession to assess) Age differences in accuracy – preschool children do not remember much, but what they do remember is accurate & important to the event. They can be cued to remember things inaccurately, though. False memories are fairly resistant to forgetting, however. Longevity of memory (rate of decay) As children age, their accuracy increases as well as the time a memory lasts. Younger children are more likely to change their recall under multiple questioning. Even 2nd graders will stick with their original recall much more than kindergarteners. Accuracy of recall declines with repeated questioning of younger children. Hypernesia is a phenomenon where amount remembered increases when people attempt to recall certain information repeatedly. Repetition does seem to facilitate performance. So repeated questioning can sometimes enhance recall, or reduce recall, or not affect it. If the questioning is not designed to corrupt memory, it can enhance the memory with the right cues. Age differences in suggestibility- all people report false information in response to misleading questioning, but children seem to be even more susceptible to manipulation, particularly when accusations or suggestions are strong and persistent. This may be due to young children’s reliance on verbatim traces, rather than fuzzy gists, which are less open to loss of memory. Source monitoring refers to being aware of the source of information we remember. We remember something, but we can’t remember how we know that thing (which is critical in eyewitness testimony). Young children have a harder time remembering how they know something. This can also contribute to their greater susceptibility to manipulation. False-memory creation isn’t that hard to do – it only requires misleading questions. Loftus did groundbreaking research on adults’ susceptibility to forming false memories with the “lost in the mall” study. College students could be induced to write about the time they were lost in the mall at age 5, as their family member had reported. 25% of college students wrote elaborate descriptions of this event and it never happened. Of the true events reported by family members, these students recalled 68%. More than 50% of preschoolers will “remember” an event that never happened after being questioned about them. They continue to remember the event even after being debriefed and told the even never happened. They have less memory for implausible than plausible events, however. In general, true memories are richer in detail and clearer than false memories, which are more generic in nature. Infantile amnesia and autobiographical memorywe generally don’t remember much from before age 3-4 years- infantile amnesia. The earliest age of meaningful recall is age 2 (hospitalization or birth of sibling) and age 3 (a move or death of a family member) We lack autobiographical memory for much more than that at such an early age. While memory for trauma can be repressed, that’s not usually what is happening here. One theory is that memory for events before 3 or 4 is encoded differently: less verbal symbolism, more imagery. So when we look back from our adult perspective/ schema, we can’t return to representations made in such different forms. Even though this theory accounts for infantile memory loss, it doesn’t cover 3 – 4 year olds, since they have verbal symbolism. What isn’t intact yet, however, is a separate sense of self. Sense of self develops over the preschool years, and until it is, events are not coded in terms of self, or meaning to self. Also, early memory formation is in terms of verbatim precise memory traces which are more susceptible to decay. It takes a child a few years to learn to develop fuzzy trace gist memories. The fuzzy traces are laid down more dependably as children enter school, which is also when memory becomes more retrievable. Their language skills are also developing in complexity, so memories are more specific and more easily represented. They learn how to remember from parents as they narrate experiences and focus on certain events/ qualities over others. This guidance is necessary in learning to code events. Hypnotic age regression is suggested as a way to determine if infantile memories are there and unretrievable through language, or simply not there any longer. When hypnotized and asked to return to preschool years, then given a conservation task, the adults acted like adults pretending to be preschoolers, but not behaving accurately. Other experiments found their actual memories were not as accurate when hypnotized as when remembering without hypnotism. Piagetian research on reconstructive memory emphasize that memory is constructive, not verbatim. We remember gists, not specifics. We add to our memories as we gain further knowledge about the world. (Memory recall is more like writing a book than reading one.) The longer gap there is between experiencing an event and remembering it, the greater chance of distortion of memory. We also distort memories when we forget how we know something or where we learned it- source monitoring error. (The author’s story about remembering his bout with the croup as a baby was interesting- since when he told his mother she said he was remembering what happened to his 6-mo.-old brother when he was 4 years old.) Development of memory strategies (mnemonics)deliberate plans used to enhance performance. Children will use multiple strategies and change as needed when solving problems. Rehearsal- a child repeats the information. Greater time used rehearsing relates to greater information storage and recall. Older children use this technique more often and effectively. o Passive rehearsal is used by younger children, repeating only one word. o Active/ cumulative rehearsal is used by older children repeating the last word and a group of as many associated words as possible. Training can enhance this skill. Organization- a child combines items into categories or units. o Clustering means remembering items from the same category together. This enhances recall, too, and it develops with age. Older children group on the basis of meaning and recall more efficiently. Younger children can be trained to do this and improve recall. Retrieval- the process of accessing information from memory for conscious use. Younger children need more cues from the original environment for recall than older ones. o Elaboration means associating two or more items by creating a representation of them. Finding some imagery that includes both items in a meaningful way. Gender differences in memory performance favor girls, as they use organizational strategies more effectively. Many studies find no differences at all. Factors that influence children’s use of memory strategies o Encoding-means how the information is represented. Younger children use fewer semantic features than older children, so there is less recall. Younger children show greater loss as a result of delay in recall. Preadolescent children do not encode information in a way so as to best organize it. o Knowledge base for the information to be remembered makes a difference. The greater familiarity the child has with a domain, the greater memory recall s/he shows. o Metamemory refers to knowledge of one’s own memory processing. We know what we know, as well as what we could not know. Remembering is a 3-part process: diagnosis (deciding what needs to be done), treatment (using the best strategies for recall), and monitoring (checking how accurate one’s memory is). Metamemory increases with age. o Motivation does impact memory development. When children are offered monetary rewards for memory, they do modify strategy use and increase memory. It also serves to keep children on task longer. Children will also spend more time on a task if they hold greater interest in it. There seems to be deeper cognitive processing on tasks a child holds greater interest in. Interest breeds success in general. o Culture and memory strategies- in Western schooling, memory strategies are taught and required to master the rote list memory used in our schools. In other cultures memory tasks may require remembering instructions or places in the environment. Overall there are few cultural differences found in memory development. Recall is related to the type of task used. (List recall is better for American children than Mayan. Location recall is better for Mayan children.) Culture also relates to what children think is essential for success. If a culture says success is dependent on hard work those children will use those strategies. If a culture says that success is due to natural talent, then the parents will try to enhance talent through various practice. Consistency and stability of memory o Domain-general or domain-specific? There is no unitary memory construct that generally increases with age. o How stable is memory performance over time? Memory is stable for tasks that don’t require strategies for recall. When strategies are required, there are changes in use of strategies over time and that affects memory performance. Forgetting and reminiscence- Forgetting is the failure of memory once something has been learned. Reminiscence is recall later of something not remembered initially (Elizabeth Smart’s sister’s memory recall after 9 mo.) Since there are developmental differences in initial learning, there are also differences in forgetting. There are fewer differences found in more realistic circumstances, though, than in controlled studies. Younger children encode in terms of verbatim memories which are more apt to be forgotten, than the gist memories that older children form. MEMORY DEVELOPMENT Memory concepts Recognition Cued recall Free recall Location memory Context-independent learning Memory development in infancy Preference for novelty paradigms Conditioning techniques- Rovee-Collier Context in memory recall Deferred imitation tasks Implicit memory Remembering events Development of event memory Script-based memory Role of parents in teaching children to remember Children as eyewitnesses Age differences in accuracy Longevity of memory (rate of decay) Hypernesia Age differences in suggestibility False-memory creation Infantile amnesia and autobiographical memory Hypnotic age regression Piagetian research on reconstructive memory Development of memory strategies (mnemonics) Rehearsal o Passive rehearsal o Active/ cumulative rehearsal Organization o Clustering Retrieval Elaboration Gender differences in memory performance Factors that influence children’s use of memory strategies o Encoding o Knowledge base o Metamemory o Motivation o Culture and memory strategies Consistency and stability of memory o Domain-general or domain-specific? o How stable is memory performance over time? Forgetting and reminiscence