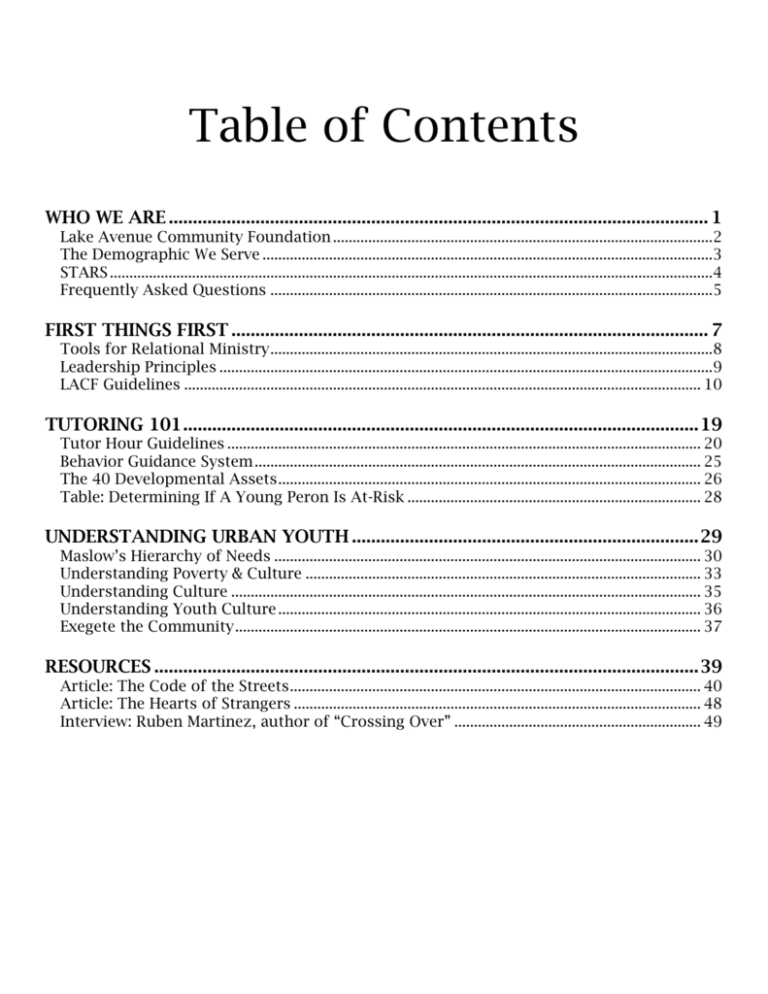

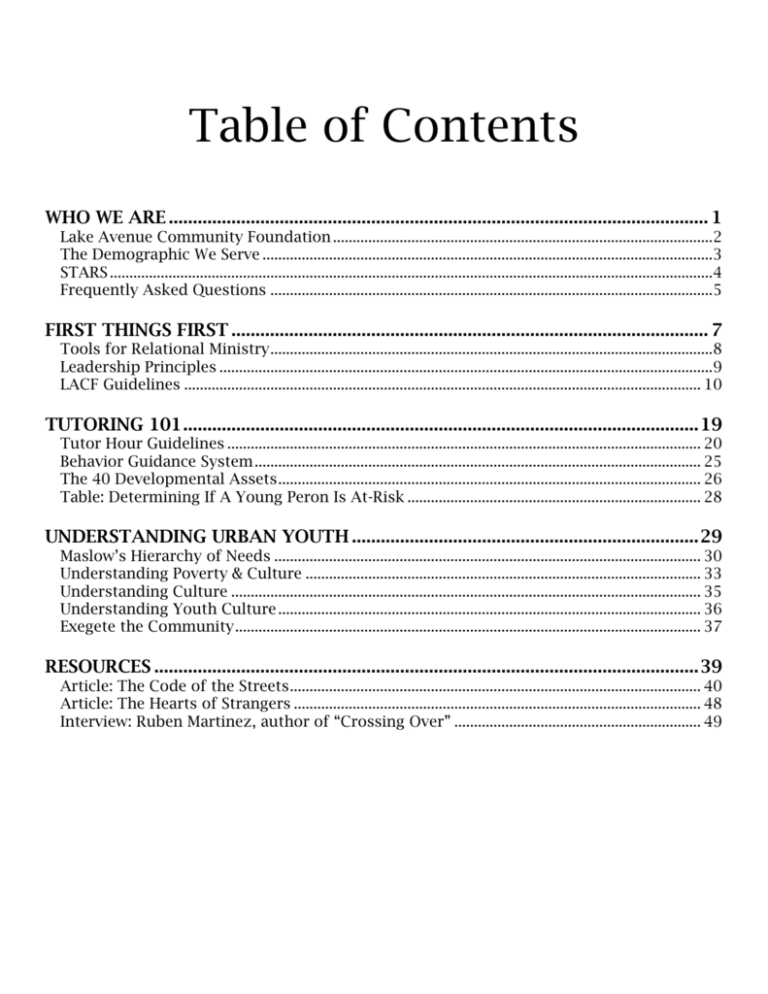

Table of Contents

WHO WE ARE ................................................................................................................ 1

Lake Avenue Community Foundation .................................................................................................2

The Demographic We Serve ...................................................................................................................3

STARS ..........................................................................................................................................................4

Frequently Asked Questions .................................................................................................................5

FIRST THINGS FIRST ................................................................................................... 7

Tools for Relational Ministry .................................................................................................................8

Leadership Principles ..............................................................................................................................9

LACF Guidelines .................................................................................................................................... 10

TUTORING 101 ........................................................................................................... 19

Tutor Hour Guidelines ......................................................................................................................... 20

Behavior Guidance System .................................................................................................................. 25

The 40 Developmental Assets ............................................................................................................ 26

Table: Determining If A Young Peron Is At-Risk ........................................................................... 28

UNDERSTANDING URBAN YOUTH ........................................................................ 29

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs ............................................................................................................. 30

Understanding Poverty & Culture ..................................................................................................... 33

Understanding Culture ........................................................................................................................ 35

Understanding Youth Culture ............................................................................................................ 36

Exegete the Community ....................................................................................................................... 37

RESOURCES ................................................................................................................. 39

Article: The Code of the Streets ......................................................................................................... 40

Article: The Hearts of Strangers ........................................................................................................ 48

Interview: Ruben Martinez, author of “Crossing Over” ............................................................... 49

WHO WE ARE

Lake Avenue Community Foundation

Lake Avenue Community Foundation (LACF) is a 501(c) (3) nonprofit organization. Created in

2001 as an independent organization to serve community needs, LACF is the driving force

behind numerous programs serving at-risk youth, the homeless, and the poor of Northwest

Pasadena.

Our four key goals with neighborhood youth are: academic success - to help students excel

academically and attend college; emotional health - to help students exhibit sound judgment, good

problem-solving skills and meet daily challenges that aid in their success and emotional well being;

economic stability - to help students become economically responsible and stable adults; and

spiritual growth - to help students develop a thriving relationship with God. This is being

accomplished through our youth programs STARS (Students and Tutors Achieving Real Success) and

Mentoring.

In addition to our work with kids, LACF facilitates an outreach to the homeless in Pasadena for Lake

Avenue Church. The Homeless and Community Outreach Program focuses on breaking the cycle of

poverty and hopelessness while encouraging and equipping men and women in developing intimate

relationships with God, the church and their families.

LACF also partners with other organizations and churches leveraging and maximizing efforts to

provide resources to economically disadvantaged communities. We exchange information, work

together to leverage resources, and undertake joint activities and initiatives in the areas of housing,

education, literacy, hunger relief, healthcare, and economic development. Should you desire more

details on our programs, please review our website at www.lakeavefoundation.org.

According to the 2000 US Census1, LACF serves a neighborhood containing the highest population

density in Pasadena, the highest household density (4,715-7,639 per square mile), the highest

household size (over 4 persons per household), and the highest Latino population density (64%, and

thus the highest density of limited English proficiency students). Another 13% of our neighbors are

African-American. LACF’s neighborhood has an estimated 6,161 youths, ages 5-19 years, per square

mile. According to the Pasadena Unified School District (PUSD) 2 of approximately 22,336 students in

PUSD, an estimated 67.7% live below the Federal Poverty Level resulting in 15, 120 students who are

eligible for free or discounted lunch at school. Moreover, in 2005, only 32% (approx.) of juniors

district-wide passed the California exit exam.

Our Mission:

As a faith-based non-profit organization, Lake Avenue Community Foundation is

unleashing the God-given potential of at-risk youth, providing the tools necessary

to thrive academically, emotionally, economically, and spiritually.

1

Local Demographics, U.S. Census, 1999 – TM-P067 Census 2000 Summary File 3

Pasadena Unified School District; Demographic profile taken in the 2004/2005 school year. www.pusd.us

2 & 3

2

The Demographic We Serve

LACF’s neighborhood has an estimated 6,161 youths, ages 5-19 years, per square mile. According to

the Pasadena Unified School District (PUSD)3 of approximately 22,336 students in PUSD, an

estimated 67.7% live below the Federal Poverty Level resulting in 15, 120 students who are eligible

for free or discounted lunch at school. Moreover, in 2005, only 32% (approx.) of juniors district-wide

passed the California exit exam. Given the condition of the public school system and the poverty

level in Pasadena, students are left with little opportunity. With a lack of opportunities and support,

these students will graduate unaware of the resources available to them.

3

Pasadena Unified School District; Demographic profile taken in the 2004/2005 school year. www.pusd.us

3

STARS

STARS takes a community-collaborative, asset building approach to after-school programming to

provide PUSD students primarily residing in NW Pasadena an obstacle-free opportunity to become

college-educated, responsible citizens of their community. By providing academic support,

enrichment opportunities and family-strengthening activities and by encouraging growing and

accountable relationships with positive adult role models (tutors), we provide an environment where

students are challenged to grow towards becoming that which God intended them to be.

Our elementary students attend four times a week and are offered literacy, math, enrichment and

tutoring activities. Our middle and high school students attend three times a week and are offered

enrichment and tutoring activities. Our registration is currently approximately 90 students. We

work closely with the LACF Mentoring Program to grow tutoring relationships into mentoring

relationships and connect our students with mentors.

Tutoring

We provide homework-based tutoring, emphasizing specific academic growth areas of the individual

student.

Technology

We provide students with internet access and specific computer skills building instruction using

various software applications as well as using a creative project-based learning approach within our

technology programming.

Reading Literacy

Using the YET (Youth Education for Tomorrow) literacy curriculum, we address our students’ need

to develop their reading skills while they enjoy a variety of literature in a fun and engaging

environment that inspires a love for reading.

College Prep and Life Skills

What are my options after high school? What classes should I be taking as a 7th, 10th or 11th grade

student? What’s the difference between community colleges, universities, private colleges and trade

schools? What is the SAT? How do I pay for college? Why will I need a checking account? What is

interest? Why is good credit important? What do I wear to an interview? How do I write a resume?

These are all questions we address with students between the 7th and 12th grades to get them

ready for post-secondary education and life.

Parent Support

We believe the family unit is the foundation of our society, and we realize that a strong partnership

with parents is essential to the success of our students. We seek to strengthen the family unit by

providing academic advocacy and coaching, parenting classes, counseling, support groups, and

other learning opportunities like ESL and technology classes to engage parents in both their

child/student’s academic process and their own educational process.

Enrichment Through Community Partnership

Together with organizations such as the Boy Scouts, the Pasadena Armory Center for the Arts, The

Outdoor Classroom and the Junior League of Pasadena, we not only provide activities that may not

otherwise be easily accessed by our students, but also model community-wide interdependence and

joint ownership of the education of our city’s youth.

Summer

Summer School – In 2010, Pasadena Unified School District (PUSD) was unable to provide summer

school due to state budget cuts, so LACF partnered with various organizations and PUSD to provide

summer classes to elementary and high school students.

4

Camps - Every summer each of our students have the opportunity to experience a week away from

home at Forest Home summer camp or on a life-changing road trip to Wyoming through our

partnership with Mentoring.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do kids need tutors?

Most of our students come from homes where English is not the primary language spoken at home.

As a result, it is difficult for the students to get homework assistance at home. Additionally, a lessthan-ideal public education system has resulted in a need for academic enhancement out-of-school.

At the present time, although long-term systemic change is necessary, we can make a difference

tutoring one or two students at a time.

Do I need teaching experience?

No. Time, willingness, patience with kids and the ability to help guide a student through basic

reading and math is enough to get started.

How do I get started?

Complete & submit the online application (www.lakeavefoundation.org/volunteer/application).

What is required of me?

We ask tutors to commit to coming for one hour (from 5:30-6:30) each week on the same day

each week.

Good relationships are important for successful tutoring, Relationships take time, and

therefore we also ask our tutors to commit to tutoring for one full school year.

We provide trainings for tutors to equip you to be the best tutor possible.

What else can I do besides tutor?

You can assist with various academic and enrichment activities, advocate for students within

the school system, or lead a small group of students towards becoming better readers.

You can mentor. (visit our website to check out the mentoring program or ask our staff)

Do I have to be a Christian to be a tutor?

As a faith-based organization, the staff of Lake Avenue Community Foundation takes seriously our

mission to unleash the God-given potential of the youth we serve, academically, economically,

emotionally and spiritually. We do not require our tutors to be Christian, but we do require all

volunteers to understand our faith-based values and to not undermine those values while

volunteering with us.

If you want to become a mentor with your student, you must be a follower of Christ. This will be

evident not only in the testimony of your relationship with God, but by the fruits of your actions

that indicate a genuine commitment and personal integrity. You must have an earnest desire to love

and serve students. You are expected to recognize how God has blessed and uniquely gifted you,

and use these blessings and gifts for equipping the student you are serving. You are also charged

with encouraging your students to discover their unique gifts, and work to develop those gifts. You

must be an active participant of a local Church for at least one year prior to becoming a mentor. We

ask that you agree to volunteer as a mentor for a minimum of one year, but prefer that your

relationship with your students continue through adulthood. We place a high priority on equipping

and training our mentors. You are expected to stay actively engaged with your mentor coach on a

regular basis.

5

6

FIRST THINGS FIRST

7

Tools for Relational Ministry

Conversion Model

The conversion model is fairly basic, showing us the approach in which to create relationship and assist in

conversion. In ministry, behavior is usually the starting place. It is thought that if you can change the

behavior, you can change the person. This line of thinking results in lessons that say “You shouldn’t do this”

or “You should do this.” But, how do you tell someone to forget their entire reality and make a behavioral

change?

It is our belief that you should begin with someone’s story and end with behavior. If you take the time to

learn what a students current reality is and how this shapes their convictions, you learn their values which in

turn creates their identity and therefore their behavior. The change here comes as you understand the

student. By establishing mentoring relationships with positive role models we focus on students at a

convictional level, which brings about marked changes in a student's identity. In turn this affects their value

system ultimately bringing about a positive change in their overall behavior and lifestyle.

Story:

You begin with a student’s story. What is their current reality? Find out who they are, where they have come

from where they are now.

Convictions:

In light of their story, talk to them about what their convictions are. What do they find is absolutely true?

Find out what makes them say this is right and that is wrong.

Values:

And from their convictions, what do they value? Friends, family, money, school, power? Have them outline

what they spend the majority of their time investing in. Have them draw it out like a pie chart.

Identity:

What you value makes up your identity. In light of the student’s values, who do they believe themselves to be?

Behavior:

Behavior affects identity. Your actions shape your life. Are you happy with this? What does this mean for

you?

8

Leadership Principles

Be Respected

Make your aim respect, not popularity.

Be Expectant

Expect the best from your students.

Be Accepting of Differences

Avoid categorizing students.

Be a Teacher

Seek to stretch: balance the physical, mental, and

spiritual.

Be Enthusiastic

Be supportive of program and activities.

Be Patient

Realize that trusting relationships take time to

develop.

Be an In-Process Person

Help students know that you are still growing,

maturing and discovering with them.

Be Honest

Be willing to admit that you were wrong.

Be a Listener

Listen for true feelings rather than surface words.

Be Understanding

Try to “feel with” a student, helping them feel

understood and worthy.

Be Affirming

Offer positive reinforcement. Compliment positive

behavior.

Be Shock Proof

Avoid shock reaction to personal “horror stories.”

Be a Confidant

Keep the trust of those who share in confidence.

Be Fair

Make any discipline fit the misbehavior.

9

LACF Guidelines

for Working with Children & Youth

The following guidelines are given to provide a framework for STARS. By accepting a volunteer

position of leadership you are agreeing to responsibly carry out the following guidelines in love.

Student Safety Guidelines

The greatest gift and asset people entrust us with is their children. It is imperative that safety be

foremost in our minds as we minister to students anywhere and at any time. Paid staff will be

certified in First Aid and CPR and all unpaid staff will be pointed out at the beginning of trips and

activities. Each department will supply a stocked first aid kit for use at all activities.

Medical Release Forms

Parent medical release forms must be obtained for every student for all high-risk, overnight, or

activities 50 or more miles away. Release forms for one-day activities shall be obtained for as many

students as is practical. In every case, the home phone number of each student shall be obtained.

Head Counts

When using transportation for activities, the number of students in each vehicle shall be counted

before departure and again before returning to be sure no student is left behind. If a student

absolutely must be left behind, a staff person will also remain and the parents notified.

Buddy System

Unless the situation allows for it, students are not permitted to go off away from the group by

themselves. The "buddy system" of accountability shall be used. Individual departments will decide

the minimum number of students in each “buddy” group.

Trip Details

Each parent or guardian will be informed of the trip details, including ending time, prior to

departure. If the group needs to change the publicized times of an activity, someone will be

appointed to meet arriving parents at the pick-up destination (or contact them by phone if possible)

and inform them of the change.

Staff/Student Ratio

The ideal staff to student ratio on large group activities should be one staff to 14 students. During

Tutoring time, a 1:2 ratio is desirable.

Staff Age Guidelines

The ideal age for a tutor is a minimum of 14 years old with no maximum age limit. Applicants

below the minimum age will be considered on an individual basis and may be brought on for a trial

period. This applies to individuals currently enrolled in middle and high school.

Scholarship Guidelines

We do not want a student to miss an activity due to inability to pay. When students have a financial

need we seek to meet this need by encouraging the student to earn the money needed for the

activity on his/her own (i.e., babysitting, lawns, etc.) or by earning Credit (service hour points

converted to dollars) by doing approved service projects. This teaches responsibility and develops

ownership.

10

Discipline Guidelines

Our ministry seeks to assist the family in raising students. Our ministry has certain standards of

conduct that we expect students to obey. Our rules are to be set out of the students' need for safety

(emotional or physical) not out of our need to control. If students disobey the set limits, we need to

respond appropriately. Frequently we will involve the parents in this so they are informed and so

they can adequately take responsibility in helping their son or daughter. Keep these principles in

mind as you discipline students:

Discipline out of love

Discipline when you are in control

Discipline then debrief

Make the consequence fit the situation

Try not to discipline or embarrass the student in front of others

Forgive and forget

Set a good example!!

State your expectations, communicate the consequences, & follow through with consistency

Counseling Confidentiality Guidelines

We recognize that a student belongs to God first and then to his or her parents. We have the

privilege of ministering under the authority of the local church with permission of the parent. We

want to recognize the primary responsibility for the student lies with the parent and our role is to

help the parent in every way possible. Ours, therefore, is a secondary role as we carry on a

concerned and loving ministry to each student.

In the light of this, it will be policy of every tutor to work with the student to keep the STARS staff

and parent informed of accomplishments and problems that may arise. Do not make promises of

confidentiality to the student. The purpose of this is to act in love to help the student and aid the

parent(s) in carrying out their responsibility.

Tutor/Student Accountability Guidelines

Relationships

No staff person shall carry on or encourage, or give the appearance of carrying on, or engage in a

dating relationship with a student. This includes not spending time alone, physical contact,

excessive communication/correspondence, or any element of romantic involvement.

Activities

Activities should be planned with safety in mind. All staff are responsible for knowing and abiding

by this entire set of guidelines when having small group times. Be creative and be sensitive to

financial restrictions that students may have.

Spouses and Families of Tutors

We recognize that mentoring will mean spending some time away from their families while working

with students. We value stability in marriages and are always looking for ways that families can

model a positive, healthy marriage and family life for students. Therefore, we encourage staff

spouses to participate in the ministry of their spouse to the extent desired and/or possible due to

family obligations.

Vehicle Guidelines

All drivers for LACF activities must be able to show valid driving license and proof of insurance if

requested by Pastor/Director. All occupants must wear seat belts properly at all times. The allowable

occupancy of any vehicle is the number of seat belts available for use. All traffic laws will be

obeyed, and the vehicle will be operated in a safe and normal driving fashion. LACF insurance will

cover damages above and beyond the individual driver’s insurance, but only as secondary insurance.

11

Child Abuse Policy

All staff shall immediately report any suspicion of child abuse of which they have knowledge of or

observe within the scope of their ministry responsibilities. They shall report the following, in

addition to as well as any other indications that may suggest the occurrence of child abuse or

neglect:

Has an unexplained injury – a patch of hair missing, a burn, a limp, or bruises

Has an inordinate number of “explained” injuries such as bruises over a period of time

Drawings in conjunction with verbal testimony

Prayer requests or written allusion

Verbal testimony

Exhibits an injury that is not adequately explained

Complains about numerous beatings

Complains about others “doing things to them when others are not at home"

Is dirty and smells or has bad teeth, hair falling out or lice

Is inadequately dressed for inclement weather

Wears long-sleeved tops during summer to cover bruises on the arms

Procedure:

If you have knowledge of or have any suspicion of abuse (physical, sexual, or emotional) or neglect

you are required to submit a Child Abuse Report Form (at the end of this section) to an LACF staff.

As a tutor, you are not a mandated reporter in the state of California, however you may still be held

liable if you fail to report abuse to the LACF staff (who is a mandated reporter). If you suspect

abuse, do not become an investigator. If your student gives you information about an abusive

situation, be clear with your student that you cannot keep that information confidential. One of the

most important determinations will be deciding if we need to call 911 to make an emergency child

abuse report (immediate intervention for safety of the child), so the more detailed the information

you have, the better.

Guidelines:

In the case that your student is participating in consensual sexual intercourse, refer to the form on

the following to page to determine if it falls under the category of abuse.

The Pastor/Director will be responsible to make all calls to either 911 or the Social Services

Department.

12

Insert abuse age guideline here.

13

14

CHILD ABUSE REPORT FORM

Please fill out this form with as much detail as possible. One of the most important determinations

will be deciding if we need to call 911 to make an emergency child abuse report (immediate

intervention for safety of the child), so the more detailed the information, the better. The

Pastor/Director will make all calls to either 911 or the Social Services Department.

Reporting Staff Info:

Today’s

Date:

Name:

Phone:

Email:

Student Info:

Name:

Phone:

Email:

Parents:

When did the abuse occur?

What were the circumstances surrounding it?

Who was involved?

Were there any past occurrences (when and who)?

If there is physical abuse involved, how was the child hit (open hand or fist), where they were hit

(physical location), and did it leave any marks (bruises or cuts)?

15

16

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF RECEIPT

My signature below indicates that I have received and acknowledge that I am responsible for reading

and understanding the STARS Guidelines (updated 08/2010) for Lake Avenue Community

Foundation. I also agree to retain these guidelines for future reference.

I understand and will support these guidelines for the integrity of the ministry, the name of Christ,

and our local church partner, Lake Avenue Church.

____________________________________

Volunteer Signature

____________________

Date

____________________________________

Volunteer Name (printed)

17

18

TUTORING 101

19

Tutor Hour Guidelines

1. Attend your scheduled weekly tutoring time each week. We understand that life happens and

there may be a circumstance that may prevent you from attending a tutoring session. If you

are unable to attend we ask that you call and let us know.

2. Arrive in a timely manner, ready to check in, grab your name tag, and start tutoring by 5:30.

3. Determine what homework the student has for the day. Do NOT assume they will tell you if

you don’t ask. (You might need to ask them multiple times!)

4. Develop a plan with your student to finish the homework. Here a few homework tips:

Start with the most difficult assignment and help the student understand how to do it.

If the student does not finish, he/she should be able to finish at home based on what

you worked through together.

If your student is having a hard time getting started, try beginning with a simple

assignment to create some good momentum for the tutoring hour.

Make sure your student has all the necessary tools to get their work done.

Teach your student how to be organized and prepared.

5. As you spend time talking with your student(s), encourage them to adhere to the student

expectations (located on page 31 and in their student folders). Their good behavior and

compliance will earn them STARSbucks!

6. Compliment student(s) as much as possible. Remember that one positive comment from you

may be the only one your student hears all day.

7. If your student is having a bad day, take the time to talk with them, ask them how they are

feeling, and pray for them. Five or ten minutes of talking with your student will be a great

encouragement for them. Afterwards, bring them back to their homework.

8. Below are some suggestions of how to lead the tutoring time with your student:

Remember, you are in charge!

Make sure your students are paying attention to their homework (not their friends,

phones, games, etc.).

Check their work when they say they are done. If they put away their work before you

have the chance to check it, ask them to pull it out again so you can look it over.

Give them work if they say they don’t have any. Both Elementary and MS/HS STARS

have resources you can get from the staff. By giving them work, they will be more

likely to bring their homework next time!

Allow your student to get up once if necessary, for water, bathroom, supplies, etc.

It is okay to say “no” to your student.

Be consistent with your rules and expectations of your student.

If you have any questions at all, feel free to ask the staff or other tutors!

9. Remember, the goal is to encourage students to appreciate learning!

10. Regularly update the Student Progress Chart in the student’s folder. This is an important tool

on which we rely for progress tracking for each student.

11. Attend STARS trainings and gatherings, designed to support you and equip you for your work

with your students.

20

Elementary STARS

Location

500 E. Villa St., Pasadena, CA 91101. It is a bright yellow house on the corner of Villa and Oakland.

You can park in the large parking lot next door.

Schedule

Elementary STARS is open Tuesdays through Thursdays from 3:30 to 6:30pm

Enrichment Activities are from about 4pm-5pm and are scheduled as follows:

1. Tuesdays: Garden Project

2. Wednesdays: Bible Study or Math (alternating months)

3. Thursdays: YET Reading Program

Circle Time (announcements & prayer) is at 5:20pm. Please come for this if you are able!

Tutoring is from 5:30 to 6:30pm. Please arrive early so you and your students can begin on time!

Student Folders

Each student has a folder which provides information regarding their grades and tutoring. The

folder will be given to you by a staff member while you are working with your student. Please look

through it and get an idea of how your student is doing. Once the tutoring hour is over, you can

leave the folder at the front desk.

Each folder contains the following:

1. Student Progress Chart (Please fill this out every time!)

2. Student rules, signed by the student

3. Recent report cards

4. STARS Personal Academic Support Plan (created at the start of each school year)

STARSbucks

Every student can earn up to 4 STARSbucks during the tutoring hour:

1. Attendance

2. Behavior/Attitude

3. Homework

4. Bonus

You can indicate on the right of the Student Progress Chart which STARSbucks the student has

earned. Be sure to give fewer STARSbucks when they did not act or do as well as they could have,

and to tell them why. Every month, STARS opens a store where the students can trade in their

STARSbucks for items like notebooks, markers, candy, etc.

Alternatives to homework

If the student did not bring homework, or has finished, you can:

1. Read – There are books marked by reading level in the library and each student knows their

level. There are also other books to choose from. You might find that having the student read

out loud helps them to focus; otherwise they can read to themselves.

2. Math – Use flashcards or create math problems.

3. Worksheets – Ask one of the staff for worksheets the student can work on.

4. Go online – Research a topic online, maybe the student’s favorite sports team or dream job.

5. Organize – Help your student put together a homework folder, or a calendar for upcoming

projects.

6. Play a game – If it is past 6:15 and you want to reward your student, play one of the games

you can find in the library.

21

Middle & High School STARS

Location

393 N. Lake Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91101

The Warehouse of Lake Avenue Church, 3rd Floor of Family Life Center

Schedule

MS/HS STARS is open Tuesdays through Thursdays from 4:30 to 6:30pm.

Tutoring is from 5:30 to 6:30pm

Student Folders

Each student has a folder which provides information regarding their grades and tutoring. The

student will bring their folder to you by a staff member while you are working with your student.

Please look through it and get an idea of how your student is doing. Once the tutoring hour is over,

the student will put away their folder.

Each folder contains the following:

1. Student Progress Chart (Please fill this out every time!)

2. Student Pledge, signed by the student

3. Recent report cards

4. STARSbucks Incentive Program description

STARSbucks Incentive Program

Every student can earn up to 10 points during the tutoring hour:

1. Attendance: up to 2 points

2. Organization: up to 2 points

3. Work Quality: up to 3 points

4. Behavior: up to 3 points

Once the student earns 120 points, they get a $5 Starbucks gift card.

You can indicate on the right of the Student Progress Chart how many points the student has

earned. Be sure to give fewer points when they did not act or do as well as they could have, and to

tell them why. There is a description of the categories in the student folders.

Laptops

Laptops can only be checked out by tutors. If your student needs a laptop, please get a laptop from

the far table. Login: starstutor, Password: student.1

Alternatives to homework

If the student did not bring homework, or has finished, you can:

1. Study tests – Help your student study for tests they may have coming up.

2. Read – Ask the staff for a book.

3. Study for standardized tests – Ask the staff for material to study for the California High

School Exit Exam (CAHSEE) for your HS student, the California Standards Test (CST) for your

MS student, or college acceptance tests (like the SATs). Your student might have some of

those materials in their folder if they have already started working on them.

4. Work on Math – Create math problems at their level, practice basic math using flashcards, or

ask the staff if there are math worksheets available for their level.

5. Go online – research a topic online, maybe the student’s favorite sports team or dream job.

6. Organize – Help your student put together a homework folder, or a calendar for upcoming

projects.

22

Tutor Hour Guidelines Receipt

I have received and read the Tutor Hour Guidelines and I agree to all of the guidelines listed.

_____________________________________

___________

__________________________________

Tutor Signature

Date

Print Name

23

24

Behavior Guidance System

Our approach to creating an environment that is conducive to academic progress, relationship and

community building is a positive approach. We ask that students follow a few simply guidelines and

we reward them as much as possible.

STUDENT EXPECTATIONS

1. Follow directions.

2. Attend regularly.

3. Respect yourself, others and your facility.

4. Give every task and activity your best effort.

5. Have fun!

Negative Consequences

The following consequences will result when a student does not adhere to the above expectations at

any time they are participating in any STARS-related activity (Loss of STARSbucks can also occur):

1.

2.

3.

4.

First offense-Warning

Second offense-Behavior Journal

Third offense-Behavior Journal & Conference and/or Call Home

Fourth offense-Suspension

Positive Consequences

1. Personal Verbal Recognition

2. Personal Written Recognition (Positive Memo)

3. Special privileges (STARSbucks earned, field trips, etc...)

25

The 40 Developmental Assets

To evaluate STARS overall and individual success, we use the objectives of the Search Foundation’s

“40 Developmental Assets”4 subscribed to us by The City of Pasadena, the Pasadena Unified School

District, and LACF. The Search Institute has surveyed over two million youth across the United

States and Canada since 1989. Researchers have learned about the experiences, attitudes, behaviors,

and the number of Developmental Assets at work for these young people. Studies reveal strong and

consistent relationships between the number of assets present in young people’s lives and the

degree to which they develop in positive and healthful ways. Results show that the greater the

numbers of Developmental Assets are experienced by young people, the more positive and

successful their development. The fewer the number of assets present, the greater the possibility

youth will engage in risky behaviors such as drug use, unsafe sex, and violence.5

Upon entering the STARS program, each student’s asset base of social and behavioral development

is measured. On average, students that enter our program have an approximately 12 of the 40

assets. By participating in this type of program, our students may immediately increase by five or

more assets. The average calculation of these measured assets allows us to accurately address the

needs of our students and the community. Based on the individual results of each student’s initial

assessment, long-term and short-term goals are then established for the overall program and

individual students. It is our goal to increase assets by one to two in an school year. We are pleased

to report that the majority of our current students are now in the 30 assets range.

Search Institute's 40 Developmental Assets are concrete, common sense, positive experiences and

qualities essential to raising successful young people. These assets have the power during critical

adolescent years to influence choices young people make and help them become caring, responsible

adults.

When you have great tutors and a well-structured program, you have great asset building

opportunity. The development assets are the science behind, it takes a village to raise a child

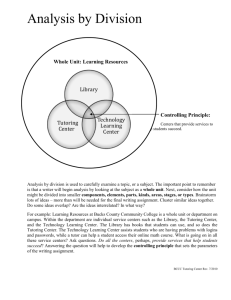

philosophy. The 40 Developmental assets fall under 8 categories: support; empowerment;

boundaries and expectations; constructive use of time; commitment to learning; positive values;

social competencies; and positive identity.

The more developmental assets, the better in the promotion of thriving and in the reduction of risk

behaviors. Survey shows that 41% of youth in grades 6-12 have between 11-20 assets. Only 9%

maintain 31-40 assets and 15% of youth have 0-10 assets.

4

5

Attachment 1; Source: www.search-institute.org/assets

http://www.search-institute.org/assets/importance.html

26

27

Table: Determining If A Young Peron Is At-Risk

Determining If A Young Person Is At Risk

Environmental Factors

HOME

Alcoholism and/or illegal drug use

Physical or sexual abuse

Harsh or unpredictable behavior

patterns

Extreme neglect: receiving little

instruction, love and discipline as a

child

A young mother

Either no contact or negative contact

with father or mother

Parent or sibling who has been

incarcerated

Parents with severe marital problems

COMMUNITY

Poorly functioning school system

with high truancy and dropout rates

Violence or strong bullying/stealing

on school grounds

Shootings and drug trade in the

immediate community

High levels of poverty

Few jobs available in community

Few or no youth in the neighborhood

who attend church or church

programs

PEERS

Strong pressure to join gangs in the

neighborhood

Peers who have been pronounced

delinquent

Absence of positive peer

relationships

Lack of a positive adult role model

Membership in a gang or a small

group that discusses and plans

antisocial behavior

Personal Factors

CHILDHOOD

Hyperactivity and attention problems

Persistent lying

Difficult temperament

ADOLESCENCE

Smoking and/or drinking before age

twelve, using marijuana before age fifteen

Struggles with depression

Persistent lying

Lack of guilt for negative actions

Lack of empathy for others

Persistent problems with authority

Binge drinking or drug abuse

Sexual activity (as a victim or an abuser)

Deep hurt that has led to self-inflicted

damage or talk of suicide

Inner rage that has led to violent acts

Preoccupation with violence and with

playing violent video games

Obsession with fantasy games and/or the

occult, death and/or the satanic

Any three factors from the “environmental” list plus three from the “personal” list indicate that

a young person is “at risk” of hurting self or others, not graduating from high school, or not

have a productive adult life. Five or more from each list indicate “high risk” of hurting self or

others, not graduating from high school, or not have a productive adult life. Less than three

from each list indicates a young person is well-adjusted.

28

UNDERSTANDING URBAN YOUTH

29

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a theory in psychology that Abraham Maslow proposed in his 1943

paper A Theory of Human Motivation, which he subsequently extended. His theory contends that as

humans meet 'basic needs', they seek to satisfy successively 'higher needs' that occupy a set

hierarchy. Maslow studied exemplary people such as Albert Einstein, Jane Addams, Eleanor

Roosevelt, and Frederick Douglass rather than mentally ill or neurotic people, writing that "the study

of crippled, stunted, immature, and unhealthy specimens can yield only a cripple psychology and a

cripple philosophy." (Motivation and Personality, 1987)

Diagram of Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

1. Physiological

2. Safety

3. Love/Belonging

4. Esteem

5. Actualization

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is often depicted as a pyramid consisting of five levels: the four lower

levels are grouped together as deficiency needs associated with physiological needs, while the top

level is termed growth needs associated with psychological needs. While our deficiency needs must

be met, our being needs are continually shaping our behavior. The basic concept is that the higher

needs in this hierarchy only come into focus once all the needs that are lower down in the pyramid

are mainly or entirely satisfied. Growth forces create upward movement in the hierarchy, whereas

regressive forces push proponent needs further down the hierarchy.

The Deficiency Needs (or 'D-needs')

1. Physiological needs (of the organism, those enabling homeostasis, take first precedence)

a. the need to breathe

b. the need for water

c. the need to eat

d. the need to dispose of bodily wastes

e. the need for sleep

f. the need to regulate body temperature

g. the need for protection from microbial aggressions (hygiene)

30

When some of the needs are unmet, a human's physiological needs take the highest priority. As a

result of the prepotency of physiological needs, an individual will reprioritize all other desires and

capacities. Physiological needs can control thoughts and behaviors, and can cause people to feel

sickness, pain & discomfort.

Maslow also places sexual activity in this category, as well as bodily comfort, activity, exercise,

etcetera.

2. Safety needs

When the physiological needs are met, the need for safety will emerge. Safety and security

ranks above all other desires. Including:

a. Security of employment

b. Security of revenues and resources

c. Physical security-safety from violence, delinquency, aggression

d. Moral and physiological security

e. Familial security

f. Security of health

A properly-functioning society tends to provide a degree of security to its members. Sometimes the

desire for safety outweighs the requirement to satisfy physiological needs completely.

3. Love/Belonging needs

After physiological and safety needs are fulfilled, the 3rd layer of human needs are social.

This involves emotionally-based relationships in general, such as friendship, sexual intimacy,

and/or having a family. Humans want to be accepted and to belong, whether it be to clubs,

work groups, religious groups, family, gangs, etc. They need to feel loved (sexually and nonsexually) by others, and to be accepted by them. People also have a constant desire to feel

needed. In the absence of these elements, people become increasingly susceptible to

loneliness, social anxiety & depression.

4. Esteem needs

Humans have a need to be respected, to self-respect and to respect others. People need to

engage themselves in order to gain recognition and have an activity or activities that give the

person a sense of contribution and self-value, be it in a profession or hobby. Imbalances at

this level can result in low self-esteem, inferiority complexes, an inflated sense of selfimportance or snobbishness

The Being Needs (also termed ‘B-needs’ by Maslow)

Though the deficiency needs may be seen as “basic”, and can be met and neutralized (i.e. they stop

being motivators in one’s life), self-actualization and transcendence are “being” or “growth needs”,

i.e. they are enduring motivations or drivers of behavior.

1. Self-actualization

Self-actualization (a term originated by Kurt Goldstein) is the instinctual need of humans to

make the most of their unique abilities. Maslow described it as follows: Self Actualization is

the intrinsic growth of what is already in the organism, or more accurately, of what the

organism is. (Psychological Rvw, 1949)

31

Maslow writes the following of self-actualizing people:

Embrace the facts and realities of the world (including themselves) rather than denying or

avoiding them.

Are spontaneous in their ideas and actions.

Are creative.

Are interested in solving problems; this often includes the problems of others. Solving

these problems is often a key focus in their lives.

Feel a closeness to other people, and generally appreciate life.

Have a system of morality fully internalized & independent of external authority.

Judge others without prejudice, in a way that can be termed objective.

2. Self-transcendence- (also sometimes referred to as spiritual needs)

Viktor Frankl expresses the relationship between self-actualization and self-transcendence in

Man’s Search for Meaning. He writes: The true meaning of life is to be found in the world

rather than within man or his own psyche, as though it were a closed system....Human

experience is essentially self-transcendence rather than self-actualization. Self-actualization is

not a possible aim at all, for the simple reason that the more a man would strive for it, the

more he would miss it.... In other words, self-actualization cannot be attained if it is made an

end in itself, but only as a side effect of self-transcendence. (p.175)

Maslow believes that we should study and cultivate peak experiences as a way of providing a route

to achieve personal growth, integration, and fulfillment. Peak experiences are unifying, and egotranscending, bringing a sense of purpose to the individual and a sense of integration. Individuals

most likely to have peak experiences are self-actualized, mature, healthy, and self-fulfilled. All

individuals are capable of peak experiences.

Maslow originally found the occurrence of peak experiences in individuals who were self-actualized,

but later found that peak experiences happened to non-actualizes as well but not as often. In his

The Farther Reaches of Human Nature (New York, 1971) he writes: I have recently found it more

and more useful to differentiate between two kinds of self-actualizing people, those who were

clearly healthy, but with little or no experiences of transcendence, and those in whom transcendent

experiencing was important and even central … It is unfortunate that I can no longer be theoretically

neat at this level. I find not only self-actualizing persons who transcend, but also nonhealthy people,

non-self-actualizers who have important transcendent experiences. It seems that I have found some

degree of transcendence in people other than self-actualizing ones I have defined this term.

Ken Wilber, a theorist and integral psychologist who was highly influenced by Maslow, later clarified

a peak experience as being a state that could occur at any stage of development and that “the way in

which those states or realms are experienced and interpreted depends to some degree on the stage

of development of the person having the peak experience.” Wilber was in agreement with Maslow

about the positive values of peak experiences saying, “In order for higher development to occur,

those temporary states must become permanent traits.” Wilber was, in his early career, a leader in

Transpersonal psychology, a distinct school of psychology that is interested in studying human

experiences which transcend the traditional boundaries of the ego.

In 1969, Abraham Maslow, Stanislav Grof and Anthony Sutich were the initiators behind the

publication of the first issue of the Journal of Transpersonal Psychology.

The above information was obtained from www.wikipedia.org.

32

Understanding Poverty & Culture

What Resources Do People Need to Succeed?

Financial: Having enough money to purchase basic goods and services.

Emotional: Being able to choose and control your emotional responses.

Mental: Having the abilities and acquired skills to deal with life’s daily activities, such as reading,

writing, computing and basic problem solving.

Spiritual: Believing in a divine purpose and habits of a group.

Physical: Having physical health and mobility.

Support Systems: Having friends, family and backup systems to meet a variety of needs.

Relationships/ Role Models: Having frequent access to appropriate and healthy positive adults.

Street Smarts: Knowing the unspoken cues and guidance of everyday life.

Ruby Payne, author of “Framework for Understanding Poverty,” says that in order to successfully

change classes from poverty to middle or upper-class, people need to have five of these eight

resources. Poverty is the #1 social determinant of high-risk behavior. Different classes value aspects

of life differently. See the charts below.

Aspect of Life

Poverty/Lower Class

Middle Class

Upper Class

Money

Food

use it and spend it

quantity is important

manage it

quality is important

Time

live in the present

live in the future

conserve & invest it

presentation is important

live in the past through

traditions

Education

Abstractly valued

survival, relationships &

entertainment

crucial for success

Driving Force

work & achievement

valuable for connections

financial, social, and

political connection

(Adapted from “Framework for Understanding Poverty” by Ruby Payne)

33

(Chart 16.1 from “Urban Poverty” by Deniz Baharoglu & Christine Kessides; http://web.worldbank.org )

34

Understanding Culture

What not to do:

A culturally unaware mentor is most likely to impose his own values and worldview onto

others or to make negative value judgments of others.

Success in a relationship recognizes that two individuals have each invested in the

relationship.

If a relationship fails, it is often the case that both individuals have not invested enough

or that communication has not been optimum.

Develop an awareness of values and biases and how they affect others.

Cultural blindness can sometimes hurt a relationship because it negates the qualities and

uniqueness of a person’s identity.

What to do:

Develop an awareness of the others history, experiences, cultural values and lifestyle.

The greater the depth of knowledge that he/she has of other cultures, the more effective a

mentor can be.

Family Culture:

Family is important in the urban setting.

Youth often grow up in expanded types of families- types that extend beyond parents and

siblings to include grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins, and even foster siblings and

relatives.

There is a strong bond and deep loyalty in these systems and should be respected.

Oftentimes outsiders are not allowed to get close to the family until trust and loyalty is

established.

Youth learn early on to protect their families; sometimes this is the only thing that the

family has control over.

Ways to build a relationship with your mentee’s family

Remember that most people are doing the best that they can.

Emphasize the person and the relationship versus the culture that surrounds and shapes

the person.

Seek to know and develop a relationship with the family as well as the youth.

Look for common ground with the youth and the family.

Recognize that people of color and low-income individuals tend to be bi-cultural, not

mono-cultural.

Remember that in spite of cultural differences, you can still affect change in a mentee’s

life.

The Culture of Urban Youth: Creativity, Resilience & Resourcefulness

Urban youth often have to make creative choices from seemingly impossible situations.

They survive despite of poverty, abuse, violence and other bad things occurring regularly

in their lives.

They survive on limited resources.

35

Understanding Youth Culture

Article by Carl S. Taylor

www.juyc.org

“Today urban youth culture is the dominating force in the life of most young people and this is not

only true throughout the United States; it is true throughout the world. Young people are connected

to each other in ways never seen before. Today’s youth are not solely dependent on their parents or

traditional means for their knowledge and opinions. More and more frequently they are independent

and as adults many of us do a very poor job of understanding them or even trying to.

Young people today are defining themselves through hip-hop culture, new breeds of alternative

music and a host of other methods. The young followers of today’s musical genres are the voices of

a new school. If America is to meet the challenges that now face our young people and our society,

we must recognize the voices of our young people; we must understand their challenges and needs.

If we are sincere in our endeavors to understand what is taking place with our young people, we

must in earnest research youth culture and we must understand their language and their symbols.

Just as Elvis was the face of rock 'n' roll and the personification of a generation, young people today

have their own faces and those with whom they identify. To denigrate or demonize the symbols and

voices of this generation only widens the gap between the old school and the new school, further

exacerbating

the

problems.

You don’t necessarily need to embrace hip-hop or other expressions of youth culture, but it’s

imperative that it be understood and respected. Failure of generations of parents and adults to

attempt to understand and communicate with young people has led to countless incidents of

suffering throughout communities. We must ask ourselves how many unfortunate circumstances

and situations might have not occurred had the proper interventions been used with a child or

young person throughout the years. Today we have the opportunity to begin a new method of

thinking and engaging our young for the betterment of our society and ourselves.”

36

Exegete the Community

On entering an urban community the first thing for the urban minister to do is slow down. Pause;

take a step back and discover the signs of God’s hand in public life. Various authors have

emphasized the fact that God has gone before us in our communities. Oftentimes Christians enter

urban communities at top speed, full of arrogance and zeal. We develop strategies for ministry and

launch projects, before we’ve adequately discerned God’s Spirit at work, before we’ve found signs of

the presence of god in unexpected places. We lack the humility of Christ, so impatient to develop

our own vision that we fail to see God quietly at work. Remember, we are working with God, not on

our own.

Learning to exegete the community takes a certain level of discipline at first but can easily be

cultivated into a natural process employed whenever one is in a new environment. The following are

some tips to use to read and assess an urban community:

1. Look at the structures

Determine what kind of structures predominate or are being built: are they residential or

commercial? They will help determine whether it is a residential, business or some other district.

The level of maintenance needed and currently employed can suggest the ability of the residents

to maintain or how invested the landowners are in maintaining the community. Also, determine

how long the buildings have been around. Usually the style and materials used can suggest the

period when the community or neighborhood was built. Are there changes in the uses of the

structures: is the theater now being used as a marketplace or a church? What other changes are

occurring? Who is leaving and who is replacing them? Why is this happening?

2. Look for "scraps of life"

Do not overlook the artifacts people leave about their property: do they reflect certain age

groups or types of households? Are they ethnically or culturally specific? Are certain values

articulated by them? Also, make note of the kinds of items or services offered by the local

businesses: Again, are they ethnically or culturally specific? Are they for the immediate

residential community, or for others from "outside?" What do the costs say about the clientele?

3. Look at the signage

Competitive marketing companies have done the demographic research and will promote

products and services in a manner appropriate to the target populations who live in or frequent

the area. Therefore, read the billboards: what is being sold? Is the language used the dominant

language of the area? Who is the target audience? Likewise read the window ads or signs placed

by business or land owners: what is being sold and for how much? Do not overlook bumper or

printed stickers as they reveal much about the people buying them: what religion or political

perspective is being espoused? Where did they go to school? What is their ethnic ancestry?

4. Look at space

No, not outer space, but how space is used. Looking at the kinds of structures in a community is

one way to assess how the local population or political powers interact with the space, i.e., how

they define it or use the land. Most urban land is defined by topology: a river or mountain range,

or by human construction, the placement of a rail system or freeway. These elements of the

natural and built environment can become demarcation lines for certain communities.

On a more personal level, living space reveals certain values or priorities that residents may hold,

for example, vehicles parked on what would be considered the front lawn or raising crops or

livestock on the land immediately surrounding the residence. In some cultures, the front yard is

an extension of the living room and everyone is welcome to participate in festive occasions. But

in other cultures, the back yard or garden area is host to private celebrations.

37

5. Sounds and smells

Exegeting a neighborhood can be a sensory experience. Keep your ears attuned to the kinds of

music played by the residents or heard on the street: Does the music cater to a specific age or

cultural group? Also, you do not need to be a linguist to appreciate different languages, as

intonations and speech patterns will differ from one group to another. If you hear many

different patterns, it may be a sign of a rich multicultural setting. Aromas can reveal preferences

in certain foods, which in turn point out the ethnicity of the resident or restaurant clientele. The

smells of an elegant boutique will certainly differ from the smells of an alleyway in skid row.

6. Look for signs of hope

Keep an eye out for evidences of God's people at work-they could be future partners and

certainly key resource people. On an immediate level, look for the presence of churches and

parachurch organizations. Read the leaflets handed out in the neighborhood or notices in the

local paper about religious activities or programs.

It will take time to get to know and be accepted by the community and to learn to work together

as a team. Make this time quality time. A thoughtful initial introductory period sets the right

tone for a collaborative spirit and the building of a good team foundation. As urban ministers

move more slowly in developing a ministry or project we open ourselves to learn from those who

came before us. As we discover signs of God's presence, a vision for ministry will evolve.

Spiritual Discovery

Unfortunately, the urban church has largely neglected this process of discovering God in the city.

The overall failure of Christians to engage in public life and to see God at work in the city has

undermined our theology and distorted our Biblical understanding. The remedy is to find ways

of identifying God at work in the city and in its people. If we have to escape the city to find God,

our understanding of who God is and of His transformative presence in urban communities is

inadequate. If we're not able to discern God in public life, our understanding of the Lordship of

Christ should be questioned. In effect, we implicitly question God's ability to survive by some of

our conduct.

Urban spirituality simply means finding God in the city. The city should be a place of hope and

growth. We need to develop the skill of living in the city as Christians while we grow spiritually

as persons, and professionally in our ministries. Urban spirituality is an art, a distinctive style of

living, of connecting what we know of God to what we understand about the complexities of the

urban world.

One of the best ways of making this connection is through networking. Networking has become

something of a buzz-word in urban ministry. However, without networks we would fail to

discern much of God's work and presence in the city. Networking is not about information; it is

about communication, the interchange of ideas and resources and the building and development

of relationships between various groups-churches, businesses, leadership and other service

organizations. In networking, the urban minister is able to identify where God's Spirit has

already planted vision, and how He has already erected signs of his Kingdom. As urban ministers

we need to identify these footprints of the Spirit, and then connect and build on them.

Once we have a strong sense of the community, and of God's presence there, it's time to look at

what it takes to build a successful organization.

- Michael Mata

38

RESOURCES

39

Article: The Code of the Streets

by Elijah Anderson

In this essay in urban anthropology a social scientist takes us inside a world most of us only glimpse in

grisly headlines--"Teen Killed in Drive By Shooting"--to show us how a desperate search for respect governs

social relations among many African-American young men

by Elijah Anderson (May 1994)

Of all the problems besetting the poor inner-city black community, none is more pressing than that of

interpersonal violence and aggression. It wreaks havoc daily with the lives of community residents and

increasingly spills over into downtown and residential middle-class areas. Muggings, burglaries, carjacking’s,

and drug-related shootings, all of which may leave their victims or innocent bystanders dead, are now

common enough to concern all urban and many suburban residents. The inclination to violence springs from

the circumstances of life among the ghetto poor--the lack of jobs that pay a living wage, the stigma of race, the

fallout from rampant drug use and drug trafficking, and the resulting alienation and lack of hope for the

future.

Simply living in such an environment places young people at special risk of falling victim to aggressive

behavior. Although there are often forces in the community which can counteract the negative influences, by

far the most powerful being a strong, loving, "decent" (as inner-city residents put it) family committed to

middle-class values, the despair is pervasive enough to have spawned an oppositional culture, that of "the

streets," whose norms are often consciously opposed to those of mainstream society. These two orientations-decent and street--socially organize the community, and their coexistence has important consequences for

residents, particularly children growing up in the inner city. Above all, this environment means that even

youngsters whose home lives reflect mainstream values--and the majority of homes in the community do-must be able to handle themselves in a street-oriented environment.

This is because the street culture has evolved what may be called a code of the streets, which amounts to a set

of informal rules governing interpersonal public behavior, including violence. The rules prescribe both a

proper comportment and a proper way to respond if challenged. They regulate the use of violence and so

allow those who are inclined to aggression to precipitate violent encounters in an approved way. The rules

have been established and are enforced mainly by the street-oriented, but on the streets the distinction

between street and decent is often irrelevant; everybody knows that if the rules are violated, there are

penalties. Knowledge of the code is thus largely defensive; it is literally necessary for operating in public.

Therefore, even though families with a decency orientation are usually opposed to the values of the code, they

often reluctantly encourage their children's familiarity with it to enable them to negotiate the inner-city

environment.

At the heart of the code is the issue of respect--loosely defined as being treated "right," or granted the

deference one deserves. However, in the troublesome public environment of the inner city, as people

increasingly feel buffeted by forces beyond their control, what one deserves in the way of respect becomes

more and more problematic and uncertain. This in turn further opens the issue of respect to sometimes

intense interpersonal negotiation. In the street culture, especially among young people, respect is viewed as

almost an external entity that is hard-won but easily lost, and so must constantly be guarded. The rules of the

code in fact provide a framework for negotiating respect. The person whose very appearance-- including his

clothing, demeanor, and way of moving--deters transgressions feels that he possesses, and may be considered

by others to possess, a measure of respect. With the right amount of respect, for instance, he can avoid "being

bothered" in public. If he is bothered, not only may he be in physical danger but he has been disgraced or

"dissed" (disrespected). Many of the forms that dissing can take might seem petty to middle-class people

(maintaining eye contact for too long, for example), but to those invested in the street code, these actions

become serious indications of the other person's intentions. Consequently, such people become very sensitive

to advances and slights, which could well serve as warnings of imminent physical confrontation.

40

This hard reality can be traced to the profound sense of alienation from mainstream society and its

institutions felt by many poor inner-city black people, particularly the young. The code of the streets is

actually a cultural adaptation to a profound lack of faith in the police and the judicial system. The police are

most often seen as representing the dominant white society and not caring to protect inner-city residents.

When called, they may not respond, which is one reason many residents feel they must be prepared to take

extraordinary measures to defend themselves and their loved ones against those who are inclined to

aggression. Lack of police accountability has in fact been incorporated into the status system: the person who

is believed capable of "taking care of himself" is accorded a certain deference, which translates into a sense of

physical and psychological control. Thus the street code emerges where the influence of the police ends and

personal responsibility for one's safety is felt to begin. Exacerbated by the proliferation of drugs and easy

access to guns, this volatile situation results in the ability of the street oriented minority (or those who

effectively "go for bad") to dominate the public spaces.

DECENT AND STREET FAMILIES

ALTHOUGH almost everyone in poor inner-city neighborhoods is struggling financially and therefore feels a

certain distance from the rest of America, the decent and the street family in a real sense represent two poles

of value orientation, two contrasting conceptual categories. The labels "decent" and "street," which the

residents themselves use, amount to evaluative judgments that confer status on local residents. The labeling is

often the result of a social contest among individuals and families of the neighborhood. Individuals of the two

orientations often coexist in the same extended family. Decent residents judge themselves to be so while

judging others to be of the street, and street individuals often present themselves as decent, drawing

distinctions between themselves and other people. In addition, there is quite a bit of circumstantial behavior-that is, one person may at different times exhibit both decent and street orientations, depending on the

circumstances. Although these designations result from so much social jockeying, there do exist concrete

features that define each conceptual category.

Generally, so-called decent families tend to accept mainstream values more fully and attempt to instill them in

their children. Whether married couples with children or single-parent (usually female) households, they are

generally "working poor" and so tend to be better off financially than their street-oriented neighbors. They

value hard work and self-reliance and are willing to sacrifice for their children. Because they have a certain

amount of faith in mainstream society, they harbor hopes for a better future for their children, if not for

themselves. Many of them go to church and take a strong interest in their children's schooling. Rather than

dwelling on the real hardships and inequities facing them, many such decent people, particularly the

increasing number of grandmothers raising grandchildren, see their difficult situation as a test from God and

derive great support from their faith and from the church community.

Extremely aware of the problematic and often dangerous environment in which they reside, decent parents

tend to be strict in their child-rearing practices, encouraging children to respect authority and walk a straight

moral line. They have an almost obsessive concern about trouble of any kind and remind their children to be

on the lookout for people and situations that might lead to it. At the same time, they are themselves polite

and considerate of others, and teach their children to be the same way. At home, at work, and in church, they

strive hard to maintain a positive mental attitude and a spirit of cooperation.

So-called street parents, in contrast, often show a lack of consideration for other people and have a rather

superficial sense of family and community. Though they may love their children, many of them are unable to

cope with the physical and emotional demands of parenthood, and find it difficult to reconcile their needs

with those of their children. These families, who are more fully invested in the code of the streets than the

decent people are, may aggressively socialize their children into it in a normative way. They believe in the code

and judge themselves and others according to its values.

In fact the overwhelming majority of families in the inner-city community try to approximate the decentfamily model, but there are many others who clearly represent the worst fears of the decent family. Not only

are their financial resources extremely limited, but what little they have may easily be misused. The lives of

the street-oriented are often marked by disorganization. In the most desperate circumstances people

frequently have a limited understanding of priorities and consequences, and so frustrations mount over bills,

food, and, at times, drink, cigarettes, and drugs. Some tend toward self-destructive behavior; many streetoriented women are crack-addicted ("on the pipe"), alcoholic, or involved in complicated relationships with

men who abuse them. In addition, the seeming intractability of their situation, caused in large part by the lack

of well-paying jobs and the persistence of racial discrimination, has engendered deep-seated bitterness and

41

anger in many of the most desperate and poorest blacks, especially young people. The need both to exercise a

measure of control and to lash out at somebody is often reflected in the adults' relations with their children.

At the least, the frustrations of persistent poverty shorten the fuse in such people-- contributing to a lack of

patience with anyone, child or adult, who irritates them.

In these circumstances a woman--or a man, although men are less consistently present in children's lives--can

be quite aggressive with children, yelling at and striking them for the least little infraction of the rules she has

set down. Often little if any serious explanation follows the verbal and physical punishment. This response

teaches children a particular lesson. They learn that to solve any kind of interpersonal problem one must

quickly resort to hitting or other violent behavior. Actual peace and quiet, and also the appearance of calm,

respectful children conveyed to her neighbors and friends, are often what the young mother most desires, but

at times she will be very aggressive in trying to get them. Thus she may be quick to beat her children,

especially if they defy her law, not because she hates them but because this is the way she knows to control

them. In fact, many street-oriented women love their children dearly. Many mothers in the community

subscribe to the notion that there is a "devil in the boy" that must be beaten out of him or that socially "fast

girls need to be whupped." Thus much of what borders on child abuse in the view of social authorities is

acceptable parental punishment in the view of these mothers.

Many street-oriented women are sporadic mothers whose children learn to fend for themselves when

necessary, foraging for food and money any way they can get it. The children are sometimes employed by drug

dealers or become addicted themselves. These children of the street, growing up with little supervision, are

said to "come up hard." They often learn to fight at an early age, sometimes using short-tempered adults

around them as role models. The street-oriented home may be fraught with anger, verbal disputes, physical