Summary: These two articles demonstrate how important capital inflows are in terms of

1) financing our government budget deficits and 2) keeping interest rates low here in the

US. The second article focuses on how these inflows have led to a booming housing

market here in the US. Ironically, the second article points out that lending standards

have loosened even though the Fed has been in a tightening cycle. This is an unusual

phenomenon and talk of a bubble in the housing market is not uncommon these days. We

will discuss these articles in detail in class. Enjoy the articles!

February 9, 2006

CREDIT MARKETS

As Deficits Rise

Bond Investors

Turn a Blind Eye

By MARK WHITEHOUSE

Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

February 9, 2006; Page C1

More than a decade ago, bond investors were widely

considered the watchdogs of government finances. Not

today.

Back in the 1990s, as deficits and government borrowing

rose, Washington worried that bond investors would rebel

against rising deficits. The fear: Investors would demand

lower prices for an increasing supply of government debt, which would drive up

yields and borrowing costs across the economy.

Contrast that with today, as the government brings back the 30-year bond amid a

new bout of deficit spending. Bond vigilantes -- investors who rebelled against

deficits in the recent past -- are nowhere to be seen, and that's rekindling an old

economic debate about the complex interplay among deficits, financial markets and

interest rates.

"I don't think the market is focusing on deficits right now," says Charles Parkhurst,

a fixed-income portfolio manager at hedge fund Archeus Capital. From his days as

a bond trader at Salomon Brothers in the mid-1990s, he remembers that Treasury

prices used to rise and fall on the release of monthly deficit data. Now, "nobody

cares," he says.

Bond-market professionals see the return of

the 30-year Treasury, which they call

simply "The Bond," as a boon, because it

revives a familiar benchmark and provides

pension-fund managers with the kind of

safe, long-term investment they need to

cover obligations to future retirees.

Traders expect strong demand at today's

auction of $14 billion in 30-year Treasurys

-- the government's first such auction in

five years. That would push prices on the

bonds higher, and thus yields lower.

Traders say the yield on the new issue

could come in as much as 0.1 percentage

point below that on the most comparable

issue, a 25-year government bond that

yields 4.68%.

"It's like welcoming back an old friend,"

says Gerald Lucas, head of Treasury and

agency strategy at Banc of America

Securities in New York.

Economists disagree about the impact that deficits have on interest rates. President

Bush said Monday that the budget deficit will reach $423 billion this year, or about

3.2% of gross domestic product, compared with a 40 year average of 2.3%.

Economic theory says that should matter. To finance the deficit, the Treasury

expects to issue a record $188 billion in new debt this quarter alone.

Theoretically, the more bonds the government issues to finance its deficits, the less

investors should be willing to pay for them, all else being equal. That, in turn,

should push up Treasury yields, punishing the government by increasing its cost of

borrowing. The higher interest rates would also hurt economic growth by making

corporate borrowing less attractive -- an effect that economists call "crowding out."

One recent study published by the Federal Reserve suggests the swing in budget

projections from surplus to deficit over the past five years should have pushed up

long-term interest rates by more than a full percentage point. Another study, done

in part by Glenn Hubbard, a former head of President Bush's Council of Economic

Advisors, finds a slightly smaller effect. Others see no effect at all.

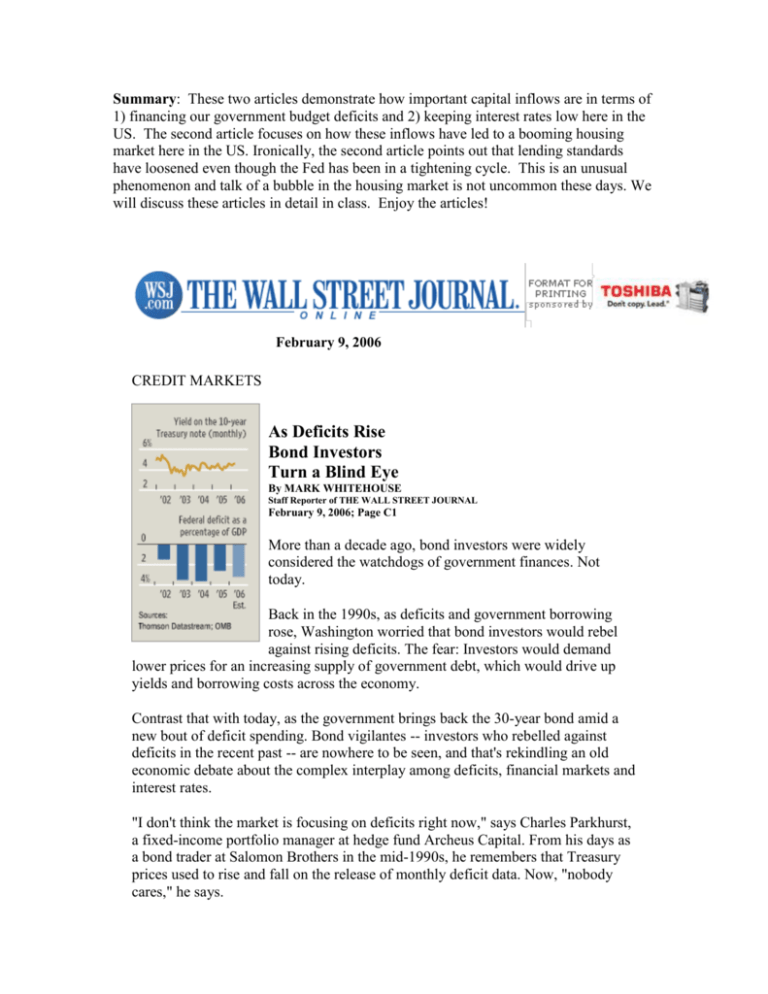

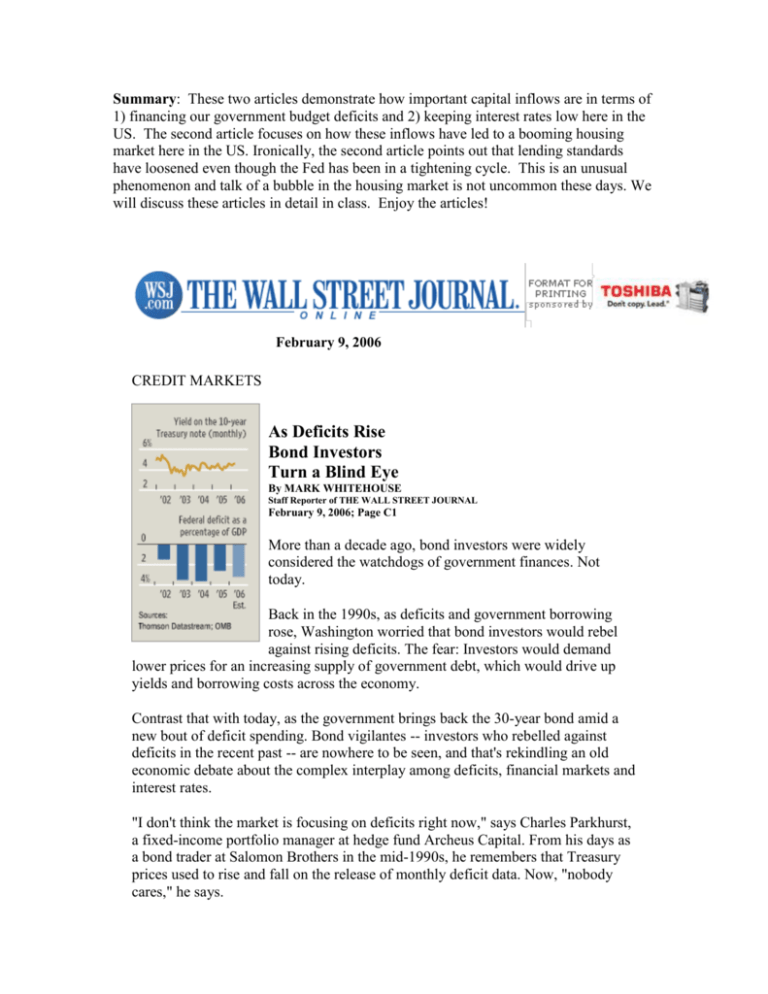

Real-world experience challenges the theory. Japan saw long-term interest rates fall

amid persistent large budget deficits in the 1990s (though the Japanese people more

than made up for the government spending by saving a lot themselves). And even

though the U.S. budget has swung from a surplus of more than $200 billion in

2000, the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note has fallen from more than 6%

then to about 4.5%.

"We've learned during the Bush administration that you can run big deficits and

there isn't any near-term pain," says Kevin Hassett, a former Federal Reserve

economist who now directs economic policy studies at the right-leaning American

Enterprise Institute. "So politicians can be irresponsible...and get away with it."

Economists and analysts offer various explanations for the twist. Most notably,

deficits don't happen in a vacuum. In both the U.S. and Japan, downward pressure

on inflation (and in Japan's case outright deflation) played a critical role in driving

down rates even as deficits mounted.

Today, some say a "global savings glut" has helped to keep U.S. rates low, as

foreigners put extra savings into U.S. bonds, pushing prices up and yields down.

Other factors are at play. For instance, some argue that total U.S. government debt

actually hasn't reached the danger zone yet: According to the International

Monetary Fund, it's about 46% of gross domestic product, compared with about

62% for Euro-area countries.

And there's the role of psychology. After the dramatic swing from deficits to

surpluses in the late 1990s, some bond investors might have stopped believing in

dire deficit projections. "Investors have the sense that the projections aren't worth

the paper they're printed on," says Bill Dudley, an economist at Goldman Sachs in

New York.

Yet some economists think investors should be paying more, not less, attention to

deficits now than they did back in the 1990s. That's because the government has

less time to correct the problem. Baby boomers will begin to retire en masse in less

than a decade, potentially causing spending on entitlements like social security and

Medicare to balloon. That, in turn, could drive government borrowing even higher.

"The situation is harder right now than it was in the early 90s," says Greg Mankiw,

an economics professor at Harvard University and, like Mr. Hubbard, a former head

of the Council of Economic Advisers. "Even if the bond market doesn't seem

concerned right now, the policy makers should be."

At 4 p.m., the benchmark 10-year Treasury note fell 5/32, or $1.56 for each $1,000

invested, to push up the yield to 4.595%. The 30-year bond fell 7/32, to yield

4.679%.

Corporate Bonds

Dow Jones & Co. Inc., publisher of the Wall Street Journal, had its long-term

credit rating cut yesterday by Standard & Poor's, which cited stiff competition for

advertising dollars and a reliance on volatile business-to-business advertising

revenues.

The downgrade to triple-B-plus affects about $470 million of debt. The outlook for

the rating is negative.

Cash flow at Dow Jones' print publishing business was weaker in 2005 than S&P

anticipated because of a modest decline in advertising revenue, S&P analyst

Michael Scerbo wrote in a report. He cited "ongoing competition in the media

space and a shift by some advertisers to more targeted advertising, particularly

online." Also reducing cash flow in 2005 were start-up costs associated with the

Weekend Edition of the Journal and higher newsprint costs.

S&P expects cash flow to improve in 2006, supported by the Weekend Edition.

"Dow Jones has a strong balance sheet supporting our strong, investment-grade

credit ratings, and the issuance of this downgrade has no impact on our borrowing

ability or our borrowing costs," said Chris Vieth, chief financial officer of Dow

Jones.

The downgrade bumps Dow Jones out of S&P's single-A rating category where

several of its peers are rated, including the New York Times Co., which has a

single-A rating from S&P, and the Washington Post Co., which is rated single-Aplus.

Dow Jones's credit profile has weakened in recent years in part because of several

acquisitions, including its purchase of MarketWatch for about $528 million.

But the new ratings provide some flexibility for further capital investments in

newspaper operations and modest-size acquisitions, S&P noted.

Rival rating service Moody's Investors Service placed Dow Jones' A2 rating under

review for a possible downgrade earlier this month.

In addition to The Wall Street Journal and its international and online editions, Dow

Jones publishes Dow Jones Newswires, Barron's and the Far Eastern Economic

Review, Dow Jones Indexes, MarketWatch, and the Ottaway group of community

newspapers. Dow Jones is co-owner with Reuters Group of Factiva and with

Hearst Corp., of SmartMoney. Dow Jones also provides news content to CNBC and

radio stations in the U.S.

---- Christine Richard contributed to this article.

Write to Mark Whitehouse at mark.whitehouse@wsj.com1

URL for this article:

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB113941361026668414.html

Hyperlinks in this Article:

(1) mailto:mark.whitehouse@wsj.com

Copyright 2006 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. Distribution and use of this

material are governed by our Subscriber Agreement and by copyright law. For nonpersonal use or to order multiple copies, please contact Dow Jones Reprints at 1-800-8430008 or visit www.djreprints.com.

was IndyMac. But the bulk of the money came from investors in Asia.”

August 24, 2005

PAGE ONE

Housing-Bubble Talk

Doesn't Scare Off Foreigners

Global Investors Gobble Up

Mortgage-Backed Securities,

Keeping Prices Strong

By RUTH SIMON, JAMES R. HAGERTY and JAMES T. AREDDY

Staff Reporters of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

August 24, 2005; Page A1

Strong demand for mortgage-backed securities from investors world-wide is allowing

American lenders to make more loans -- and riskier ones -- in a way that is helping

prolong the boom in U.S. house prices.

The cash pouring in -- not only from U.S. investors but increasingly from Europe and

Asia -- keeps stoking the housing market even as the Federal Reserve Board continues

to raise interest rates, normally something that damps home prices. The market has

shown a few signs of slowing recently, and talk of a bubble has grown louder, but

prices continue to rise or remain at lofty levels as investors continue to gobble up

mortgage-backed securities and banks keep

lending.

HOUSING BOOM

1

Read more about the housing

market2 and see home-buying

calculators and resources.

"As the Fed has tightened, lenders have eased"

terms for borrowers, says Mark Zandi, chief

economist at Economy.com, a forecasting firm

in West Chester, Pa.

Investment banks and other firms have been

buying mortgage loans from lenders and

packaging them into securities for sale to

investors since the 1980s. But investor

demand has surged in recent years, largely because in an era of low returns, mortgagebacked securities offer yield-starved investors much higher returns than government

bonds.

U.S. lenders will make about $2.8 trillion in home-mortgage loans this year, according

to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

The MBA estimates that about 80% of

these loans will end up in mortgagebacked securities. Mortgage-backed

securities outstanding at the end of the

first quarter totaled $4.61 trillion, up 61%

since the end of 2000. In the same period,

total Treasury securities outstanding grew

35% to $4.54 trillion.

Investors' strong demand for mortgage

debt, besides allowing lenders to offer

many borrowers better terms, has also

made it easier to offer mortgages to

borrowers who might not easily qualify

for a loan. The growth of the mortgage

markets spreads the risks around. But

some mortgage-industry analysts say

lenders have become less stringent in

their loan terms because they can sell

almost any type of loan to those who

package mortgage securities for investors.

"Loose lending standards are probably the single biggest thing fueling the speculative

fever we have today" in housing, says Kenneth Rosen, an economist who is chairman

of the Fisher Center for Real Estate at the University of California at Berkeley.

In a world of low interest rates, the market for mortgage securities is simply too big

and profitable for many investors to ignore. Investors can earn about 5.5% on

mortgage securities whose payments are guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac,

government-sponsored companies. Those who can stomach greater risk can buy

subprime mortgage securities, which come with no guarantee but can yield as much as

15%, according to Bear Stearns. By contrast, 10-year U.S. Treasurys yield about 4.2%;

the equivalent government securities in Germany yield about 3.2% and in Japan 1.5%.

The buyers of mortgage-backed securities include U.S. pension funds, hedge funds and

insurance companies. But overseas investors are the fastest-growing source of demand.

The trade publication Inside MBS & ABS estimates that foreigners held $280 billion

of U.S. mortgage securities at the end of 2004, or 6% of the total outstanding. The

foreigners' holdings rose 26% last year and have continued to bound ahead so far this

year, Inside MBS & ABS says.

"There's this insatiable appetite for mortgage-backed securities world-wide," says

Andrew Sciandra, a senior vice president at IndyMac Bancorp, a California thrift,

who heads a team that creates those securities. In the past year, Mr. Sciandra has met

with investors from places like Germany, France and Abu Dhabi. Asian investors now

account for roughly 10% to 20% of mortgage securities sold by IndyMac.

For homeowners, the growing international demand for mortgages means it's

increasingly likely that the money they borrow to buy a home or refinance their

mortgage is coming ultimately from outside the U.S. When Claude Gaty, a chef and

co-owner of a bistro in Las Vegas, recently refinanced the mortgage on his fourbedroom Las Vegas home, the lender was IndyMac. But the bulk of the money came

from investors in Asia.

IndyMac pooled Mr. Gaty's loan with about 3,000 other mortgages that carry a fixed

rate for the first three, five or seven years. Mr. Gaty is paying both principal and

interest on his loan, but most of the loans in the pool are interest-only mortgages,

which allow borrowers to pay no principal in the early years. When the $650 million

offering of triple-A rated bonds backed by these mortgages came to market in June, it

drew more than a dozen investors from Europe, Asia and the U.S., according to

Deutsche Bank, which handled the deal. Such bonds typically yield 0.75 to 1.15

percentage point more than Treasurys, Deutsche Bank says.

The most recent entrant to the market is China. Its banks are rich with deposits from

Chinese companies that earn dollars exporting to the U.S. Dollars have also been

handed to some banks by the government in Beijing as part of its efforts to strengthen

their balance sheets.

Until a few years ago, Chinese investors restricted U.S. investment mostly to

Treasurys. Now, to boost their yields and because they consider the market safe,

bankers from a number of institutions say they are devoting more of their portfolios to

mortgage securities. Some bankers say their goal is to have 40% of their U.S. dollars

in asset-backed securities.

China's government also is testing U.S. mortgage investment. The country's Bank of

Communications, the only bank with a mandate to help manage China's $700 billion of

foreign-exchange reserves, has recently put a sliver of those reserves into mortgage-

backed issues, according to a banker there. The State Administration of Foreign

Exchange, the government agency in charge of the reserves, declined to comment.

Zhu Kai, who helps manage U.S. dollar investments at Bank of China, says in a rare

interview that his mortgage-backed portfolio has "plenty of room to grow." Mr. Zhu

expresses confidence in the U.S. dollar and the health of the U.S. home market.

Housing is so vital to the U.S. economy, Mr. Zhu and some of his counterparts at other

Chinese banks reason, that U.S. authorities will prevent a bust.

Even the recent decision by the Chinese government to raise the value of its currency

by about 2% isn't likely to lead Chinese banks to shift their plans. "The timing may be

a little bit surprising but we will not change our investment portfolio," Mr. Zhu says.

While Asian investors have largely focused on triple-A-rated bonds, other investors

are buying lower-rated debt. These bonds, which are created when bankers carve up

pools of mortgages, offer higher yields, but also bear the first risk of losses should

borrowers default. Investors who buy these bonds in effect set the standards for which

mortgages are made by deciding how much extra yield they need to compensate for

the added risks of lower-quality loans. They include real-estate investment trusts,

hedge funds and investors from Europe.

Strong investor interest has also made loans available to borrowers with poor credit

and many other people who might otherwise have trouble getting a mortgage.

Subprime loans included in mortgage securities totaled $401.5 billion last year, nearly

double the total for 2003, according to Standard & Poor's. Meanwhile, loans with less

than full documentation of the borrower's income and assets accounted for 70% of

mortgage securities rated by Standard & Poor's in this year's first half, double the level

recorded in 2000.

"There's no question that [lending] standards have loosened over the past couple of

years," says Arthur Frank, director of mortgage research at Nomura Securities

International in New York. If house prices fall, "you may well have some pretty

serious credit problems," hurting holders of the lower-rated mortgage securities.

Mr. Zhu, the Chinese fund manager, is sanguine, for now. The U.S. housing market is

"maybe losing a bit of steam," Mr. Zhu says. "I think the monetary authorities, they

don't want this housing market to burst. I don't think it is a bubble. But if things go on

like this for another five years, it's a different story."

Write to Ruth Simon at ruth.simon@wsj.com3, James R. Hagerty at

bob.hagerty@wsj.com4 and James T. Areddy at james.areddy@wsj.com5

URL for this article:

http://online.wsj.com/article/0,,SB112484869024321472,00.html

Hyperlinks in this Article:

(1) http://online.wsj.com/page/0,,2_1176,00.html

(2) http://online.wsj.com/page/0,,2_1176,00.html

(3) mailto:ruth.simon@wsj.com

(4) mailto:bob.hagerty@wsj.com

(5) mailto:james.areddy@wsj.com

Copyright 2005 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. Distribution and use of this

material are governed by our Subscriber Agreement and by copyright law. For nonpersonal use or to order multiple copies, please contact Dow Jones Reprints at 1-800843-0008 or visit www.djreprints.com.