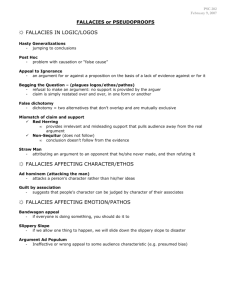

Logical Fallacies

An important academic skill is detecting and avoiding logical fallacies. An argument commits a logical

fallacy when its validity rests upon irrelevant appeal, improper generalization, false assertion of cause,

or questionable assumption. This handout identifies general categories and discusses specific types of

fallacies. An example and explanation is given for each type.

This handout aims at helping students academically, but it is limited to a brief overview. For certain types

of fallacies, it is difficult to provide brief examples that clearly correspond to academic writing. Many

academic fallacies are often understandable only in terms of comprehensive contexts. The purpose of

this handout is to teach principles, and it is hoped that an understanding of these principles will aid

students within specific academic contexts.

Irrelevant Appeals

One way an argument commits a fallacy is by relying on an irrelevant appeal. A superstar lawyer might

identify this appeal by rising to his feet and shouting, “Objection! Irrelevant!”

Popular appeal

The argument relies on widespread acceptance, not logic.

Example:

You can’t get uptight about copyright infringement. Everyone owns illegally burned

CDs and illegally copied music.

By hiding behind Everyone, this argument avoids the logical possibility that the prevalence of

copyright violation might be all the more reason to be uptight about it.

Irrelevant appeal to authority

The argument relies on an irrelevant appeal to authority. Some appeals to authority are relevant, such as

appealing to recognized authorities for claims within their areas of expertise. Beware, however, of

authorities justifying claims outside of their expertise.

Example: Psychiatry is a pseudo-science. Why else would Tom Cruise criticize it?

Even if he is right, Cruise is not a recognized authority on psychiatry or philosophy of science issues.

Appeal to ignorance

The argument relies on the mere absence of contradictory knowledge or evidence.

Example:

Of course God exists. No one has ever proven that he doesn’t.

The fact that no one has refuted God’s existence is not proof of his existence. (The same could be said

for the reverse argument: the fact that no one has “proven” that God exists is not proof that he does

not.)

Ad hominen (Argument against the person, or “attacking the person”)

The argument relies on irrelevant characteristics of persons associated with an opposing argument. In

many cases, this tactic is essentially the same as name-calling.

Example:

You can’t take Martin Heidegger’s criticisms seriously. After all, he was a Nazi.

This argument avoids the merits of Heidegger’s actual criticisms. (It is often easier to label others as

evil, crazy, or stupid than it is to logically evaluate their disagreeable claims.)

Straw person (Straw man)

The argument transforms an opposing argument into an indefensible claim, and equates that claim with

the original argument. This type of argument is often introduced by a phrase such as, “What so-and-so

really means to say…” (Graybosch et al., p. 156).

Example:

Mr. Stewart says that concealed weapons should not be allowed in public facilities

such as college campuses. But those who carry concealed weapons are only concerned

with defending themselves. Does Mr. Stewart think we shouldn’t be allowed to defend

ourselves? (Adapted from Carter, p. 93)

This argument shifts attention from the right to carry a concealed weapon to the right to defend

oneself—implying that being deprived of a concealed weapon is the same as being deprived of any

self-defense at all.

Emotional appeal

An emotional appeal is sometimes appropriate, but an argument commits a fallacy when it relies on an

irrelevant emotional appeal at the expense of logic. It may appeal to pity, force, patriotism, guilt, or

star-crossed destiny, to name a few.

Example:

Across the Pacific, heroes bravely fight with the spirit of General Washington,

risking their lives for Freedom’s sake. Yet in our own land, vermicular protesters put a

torch to the flag, making a mockery of the blood that was spilt for them! Any true

American—not ashamed of the banner that yet waves—will stand proudly in support of

our troops in Vietnam, and the valiant efforts of their courageous leader, Richard M.

Nixon.

This argument dodges the logical validity for supporting Nixon, relying instead upon an irrelevant

emotional appeal. In particular, it uses patriotic rhetoric—not logic—to claim what it means to be a

true American.

Improper Generalizations

Another way an argument commits a fallacy is by producing or relying on improper generalization.

Traditional scientific progress requires generalization, but certain types of generalization are not

logical.

Hasty generalization

The argument makes a broad generalization based on scanty or inconclusive evidence.

Example:

I’m never asking out a redhead again. I’ve gone out with three redheads, and each

one had a fiery temper.

In the context of the original argument, this statement implies that all or most redheads have fiery

tempers. Logically speaking, the three cases might be a mere coincidence. (A larger, random sample

could logically justify a probable claim—this is the heart of much scientific research.)

Unqualified generalization (Dicto simpliciter)

The argument begins with a simple claim, and then generalizes that claim to a situation which must be

qualified to be accepted.

Example:

All other things being equal, an overweight person who begins jogging regularly will

weigh less than one who does not. So if you need to shed a few pounds, unbury those

jogging shoes and get moving!

The first claim is so general that it is virtually indisputable. The concluding recommendation,

however, is an oversimplified generalization: jogging is not a good choice for many overweight

people, such as those with bad knees or severe osteoporosis—or those who adequately exercise in a

different way.

Composition

The argument generalizes that if all the parts of a whole have a given property, then the whole must also

have that property.

Example:

If all of the players for the Dallas Mavericks are good, then the whole team must

be good.

Not necessarily. It’s possible for a team to be filled with tremendous players who, for whatever

reason, do not play well as a team. The whole does not always equal the sum of its parts.

Division

The converse of composition, this argument generalizes that if something has a certain property, then its

parts have that property also.

Example:

The American Psychological Association (APA) endorses the legalization of samesex marriage. Dr. Smith is a member of APA. Therefore, Dr. Smith supports the

legalization of same-sex marriage.

Without a premise, such as “APA members must support the group’s collective policies,” it does not

logically follow that Dr. Smith supports same-sex marriage. And, in fact, he does not—nor is it

required for a member of APA to do so. The parts do not always reflect the whole.

Slippery slope

The argument takes several ideas that are related to each other by varying degrees and inappropriately

makes a generalized statement about them all.

Example:

You might call Mrs. Jones a psychopath for murdering her husband without

remorse. But she’s not alone. Dr. Zirktof maintains a poker face as he mechanically

inserts forceps into half-birthed babies every day. And my neighbor Ned Farkas coldly

fires his shotgun at many an innocent deer. And I once saw your nephew Billy playfully

squash an innocent spider. So if Mrs. Jones is a psychopath, so is little Billy.

This argument equates Billy with Mrs. Jones without accounting for the vast difference between

them. If a generalization can be made about the two, it should be demonstrable without the

intermediary premises about Dr. Zirktof and Ned Farkas. Omitting these premises clearly reveals that

more support is needed for a logical claim.

Questionable analogy

The argument takes an analogy that is related in one way, and generalizes the relationship in a way that is

not appropriate.

Example:

I know we’ve only dated for two months, but I feel confident about asking Becky to

marry me. After all, you don’t have to eat a whole cake to know that the cake is good.

(Adapted from Shulman.)

This analogy might express one’s hope, faith, or intuition, but it cannot be used as a logical reliance.

In one sense, the goodness of a short-term relationship can be compared to the goodness of a slice of

cake. The analogy flops, however, in the arena of long-term commitment. Alas, even the best cakes go

stale in time.

False Assertion of a Cause

The third type of fallacy is a false assertion of cause. Because traditional scientific progress thrives upon

discovering causes and effects, it is important to be able to detect and avoid this type of fallacy.

Oversimplified cause

The argument attributes a causal relationship as being the only possible cause, when in reality other

causes may have contributed to the effect.

Example:

If those two missionaries wouldn’t have knocked on my door 14 years ago, I

wouldn’t be a member of the Church today.

This tribute is touching, but it commits a logical fallacy. Perhaps missionaries would have knocked on

the person’s door 12 years ago, or 7 years ago, or perhaps not at all, and yet he might have joined the

Church another way.

Post hoc (“after this”)

A type of oversimplified cause, this argument attributes a causal relationship based merely on the grounds

of an event preceding a proposed effect.

Example:

Are you sure you want to go to Berkeley? My uncle went there and he lost his faith

and left the Church.

Although the uncle went to Berkeley before he started losing his faith, it is not necessarily a

contributing cause.

Questionable cause

The argument attributes a causal relationship based on “token evidence, such as a correlation that has not

been subjected to further investigation” (Graybosch et. al, p. 160).

Example:

Studies show that married American adults, on average, are happier than nonmarried ones. Clearly, marriage leads to greater happiness.

This argument confuses causation with correlation. It is not clear why married Americans are

happier—it might be that happier people are more likely to get married. Similar issues are raised

concerning TV exposure and violence, or presidential policies and economic stability

Questionable Assumptions

Finally, an argument commits a fallacy by relying upon questionable assumptions that distort the

argument’s claims. Often this is unintentional, but it is fallacious nonetheless.

Begging the question (Circular argument)

The argument has no strength without assuming beforehand the thing it wishes to prove.

Example:

X:

Of course God exists?

Y:

How do you know?

X:

God is in the Bible, of course!

False dilemma (False dichotomy)

The argument assumes that only one of two choices is possible, when in reality other alternatives exist.

Example: If you want better public schools, you have to raise taxes. If you don’t want to raise

taxes, you can’t have better schools. (Ignores other alternatives, such as spending

existing tax money more efficiently).

In the context of the original argument, this question is a rhetorical one that cleverly (or naïvely)

assumes that only two options exist. In reality, a third explanation such as ignorance, moral weakness,

or outright rebellion—which might have nothing to do with apathy—may be possible.

Equivocation

The argument assumes that two or more inconsistent terms are the same.

Example:

The Bible says that Jesus was liberal. That’s why I think it’s funny that so many

Christians are conservatives.

Whatever the similarities, the biblical use of “liberal” is not synonymous with the contemporary

political ideology to which the argument appeals.

Bibliography:

Carter, K. Codell. A First Course in Logic. New York: Pearson Longman, 2004.

Graybosch, Anthony J., Gregory M. Scott, and Stephen M. Garrison. The Philosophy Student Writer’s

Manual. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003.

Shulman, Max. “Love is a Fallacy.” The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis: Eleven Campus Stories. Garden

City, New York: Doubleday, 1951.

Dennis Wendt, Jr., Aug. 2005

Based on a handout by Natalie Stillman-Webb, Feb. 1993