1 HEADING LEVEL 1 (ALT 1)

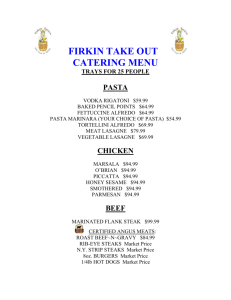

advertisement