kinds of narrators and focalisers

advertisement

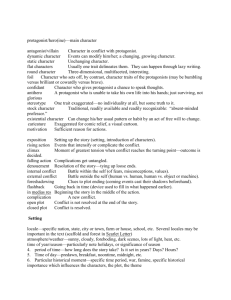

*ELEMENTS OF PLOT STRUCTURE Exposition: providing the background information (its opposite is beginning in medias res) Conflict: not a particular moment or episode in the narrative/drama, but the fact that there are opposing forces in it. The conflict is the generating force of the narrative/drama, that which produces a story. The conflict can be external (between individuals and groups, or between the individual and society Julien Sorel and the unheroic world around him and internal conflict. Crisis: the moment/period when the conflicting forces are activated Climax: the moment of highest intensity Anticlimax: this is not a necessary property of the plot. It occurs when we expect a climactic moment, suspense is generated, but instead of the climax we have something trivial, a non-event (e.g. when someone holds someone else at gunpoint and we expect the gun to go off every minute, and in the end there is only a click and the gun does not work, or there is no bullet in it, etc.) Resolution (Dénouement) of the conflict: when the conflict is solved, tension falls In medias res: beginning in the middle of the action, and providing the necessary information later in the narrative Foreshadowing: referring to the future in a narrative; anything might be a foreshadowing (for instance, as Chekhov famously said, if there is a “the gun on the wall” during the play, it will go off sooner or later). Here is an example of a particularly effective foreshadowing: “On the day he was killed, Santiago Nasar got up at half past 5 in the morning in order to see the arrival of the bishop’s boat” (Gabriel García Márquez: Chronicle of a Death Foretold); Because the death is foretold, we read every sentence of the narrative as stages of a journey leading to the protagonist’s death (cf. the opening sequence of American Beauty) Flashback: referring to the past in a narrative Suspense: creating a sense of mystery, a missing piece of information, a secret in a character’s past, increasing the tension in the reader/viewer, for instance by indicating that something terrible will happen but in an ambiguous way, not letting us know precisely what will happen. Some types of narrative are dominated by suspense (detective stories, thrillers). Delay: the devices the narrative uses in order to put off the ending, to keep our interest alive (e.g. inserting sub-plots, talking about minor characters, offering descriptions etc). In detective stories, the most frequent strategies of delay are offering false clues. Teleology (teleologikusság, célelvűség, célképzetesség; see also handout) means “having a final aim or objective”, the sense that every element (of a narrative, for instance) is moving towards this final aim and that every element makes final sense in the light of this objective. This final objective or aim towards which everything is leading is called a telos (“télosz”). The Bible, for instance, is a narrative that is teleological, starting with Creation and ending with the Apocalypse and then the Kingdom of Heaven (which is its telos); every little detail of the Bible gains its final meaning only in the light of the telos. European culture tends to be teleological in nature: the stories (private and public) that we tell, from fairy tales through love stories to political plans, are mostly teleological. This, plots are plots because, in them, everything is moving towards the final goal/objective (telos), every detail gets its significance in view of the final goal. *PERIPETEIA Peripeteia (reversal): Aristotle’s term: Peripeteia is a basic element of plots. It means a turning upside down, a basic turning point in the narrative/drama. It is important to note that the reversal is not itself an event: it means the reversal of our perspective upon the action. The best example is that of the story of King Oedipus: for a long time, he is in charge of the investigation after King Laius, unaware of the fact that the King was his own father and that in fact he is investigating after himself. The reversal is the moment when he realises that he has been investigating after himself, that he is detective and murderer in one person. No new event has occurred, nobody has been killed etc. The peripeteia is simply that all of a sudden everything turns upside down, what we thought was white turns out to be black, and vice versa. We have to reinterpret the whole story in light of the new knowledge, from the new perspective. Peripeteia is obviously crucial in detective stories; in Agatha Christie’s novels there are usually several such reversals: each time we are certain about the guilt of one character, but suddenly everything is put in a new perspective and our opinion changes. A good example is provided by the film The Sixth Sense: it is only at the end of the film that the psychiatrist protagonist Dr. Malcolm Crow (Bruce Willis) realises together with the spectators that he has been dead for a year. Thus, although there is no new turn in the plot, our perspective immediately changes, and we see the whole film from an entirely different perspective, understanding certain little details that have so far been incomprehensible (for instance, why Bruce Willis was ignored by many characters, including his ex-wife). Another well-known example is the film A Beautiful Mind (Egy csodálatos elme), based on the life of the Nobel-prize winning mathematician John Nash: about halfway through the film it turns out that three of the main characters of the film (including a CIA agent, a university friend and his niece) are the products of Nash’s schizophrenic mind. Thus, since the camera does not distinguish between “real” characters and “imaginary” characters, the viewers of the film are forced to switch their minds and revaluate everything thay have seen so far. *KINDS OF NARRATORS AND FOCALISERS There are various ways of distinguishing between kinds of narrators and focalisers, that is, various ways of grouping them. Here are three ways of classifying narrators/focalisers. 1. Extent of participation in the story non-participant narrator: a voice outside the story, not belonging to a character (e.g. Stendhal’s The Red and the Black) participant narrator: the narrative voice belongs to one of the characters. The character-narrator can be the protagonist (as in Dickens’s David Copperfield or Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye) or a minor character (as in Melville’s Moby Dick, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby or Kerouac’s On the Road) 2. Extent of knowledge about the story This classification refers to third-person, non-participant narrators omniscient narrator/point of view: that which knows what goes on in the characters’ minds, knows what happens in different places at the same time, knows the past of the characters, etc. Such omniscient narration is frequent in 19th-century realism (e.g. Jane Austen or George Eliot), as well as in popular fiction. limited omniscience: when the narrator sees into the mind of one/more characters, but his/her knowledge is not total (for instance, the novels of Henry James, including The Portrait of a Lady) ordinary knowledge: knowing as much as an ordinary person would (usually participant; for instance, Philip Marlow, the narrator of Raymond Chandler’s hard-boiled detective stories) unknowing narrators or focalisers: narrators who know less than an ordinary person would know: Beckett’s fiction (Molloy); focalisers with the same limitations are typical of the texts of Kafka (e.g. The Trial). 3. Extent of involvement emotional, moral involvement: to what extent does the narrator express his/her opinion about the events and characters editorial narrator: expressing his/her views and judgements about characters and events (most nineteenth-century fiction, including Jane Austen, George Eliot) impartial narrator: no opinions are exressed, no side is taken (Gustave Flaubert’s novels, or much modernist fiction: Joyce, Joseph Conrad, William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf) Other kinds of narrators unreliable narrator: a narrator who cannot be trusted. The reasons for this can be manifold: moral unreliability (he is lying in order to mislead us); emotional unreliability; mental disorder (e.g. if the narrator is an idiot, like Benjy in the first part of Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, or in Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart”) naïve narrator: a narrator who does not fully understand the story s/he is telling; the reader is expected to correct the naiveté of tha narrator (e.g. child narrators talking about adult things, with absolute sincerity and truthfulness, but without fully understanding what they are talking about; Forrest Gump, the narrators of Kurt Vonnegut) skaz: a narrative technique that imitates oral narration, giving the impression of someone talking to us, with frequent references to the situation of telling, frequently adressing the listener (Bohumil Hrabal, Salman Rushdie) self-reflexive narrator: a narrator who is aware of the fact that s/he is narrating a story, and who comments on his/her situation as narrator, reflecting upon him/herself as narrator (difficulties of narrating, of remembering details, etc.), e.g. Tristram Shandy. Here is an example frm Salman Rushdie’s 1981 Midnight’s Children, in which the narrator is telling his story to a woman called Padma in a pickling factory: “But here is Padma at my elbow, bullying me back into the world of linear narrative, the universe of what-happened-next: »At this rate«, Padma complains, »you’ll be two hundred years old before you manage to tell about your birth.You better get a move on or you’ll die before you get yourself born«” multiple point of view/narrator: when the same events are seen from more than one points of view/narrated by more than one narrators (William Faulkner: The Sound and the Fury; Lawrence Durrell: Alexandria Quartet) shifting point of view/voice: when different parts of the action are seen from different points of view/narrated by different voices (e.g. Virginia Woolf: Mrs. Dalloway) In both cases, the narrator dissolves in the minds of the character or characters, there is no totalising view. *NARRATIVE TECHNIQUES OF REPRESENTING HUMAN CONSCIOUSNESS internal monologue: it is first-person language used within a novel that is otherwise narrated in the third person by a non-participant narrator. In passages of internal monologue, the narrator’s voice disappears, we are fully inside the character’s head: it is silent speech (not soliloquy), the thoughts of the character. It is as if we overheard his/her thoughts. Internal monologue stays at the level of language and conscious thought: sentences are grammatical, logical, possible though not always very easy to follow. The second sentence of the quotation above is a short example of internal monologue: “I can’t bear it, Julia said to herself, it’ too wonderful, it’s too much. If we go now everything will come right, but if only we go this instant minute, it must be at once, oh, please” (Henry Green: Party Going) In the second sentence, the narrator “disappears” (there are no grammatical traces of his/her presence), and we are within the head of the character. stream-of-consciousness technique: here the narrator completely evaporates, we are fully inside the mind of the character. The stream-of-consciousness technique conveys not just the character’s thoughts but also his/her sensory impressions, memories, associations. Stream-of-consciousness technique wants to create the illusion that we are actually watching the way a human mind works, jumping from a thought to a physical sensation, trying to represent the way our mind works before we formulate our thoughts in language. Also the stream-of-consciousness technique is trying to suggest things about the character’s unconscious, thus we know more about the character than him/herself. Therefore, it is ungrammatical, not logical, “below” the level of conscious thought and language. Often there are no full sentences; the effect is that of a very private world, a world like the world in the head of each of us almost impossible to understand for others. Stream-of-consciousness technique was a favourite device of Modernist literature (early 2th-century writers: Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner, etc.). Here is an example from Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), showing Leopold Bloom entering a small grocery store and looking around inside: “His eyes unhungrily saw shelves of tins: sardines, gaudy lobster’s claws. All the odd things people pick up for food. Out of shells, off trees, snails out of the ground the French eat, out of the sea with bait on a hook. Silly fish learn nothing in a thousand years. If you didn’t know risky putting anything into your mouth. Poisonous berries. Roundness you think good. gaudy colou warns you off. One fellow told another and so on. Try it on the dog first. Led on by the smell or the look. Tempting fruit. Ice cones. Cream. Instinct.” The narrator “disappears” in the second sentence, and from this point, we are in the mind of Bloom, following his thought, and the text is entirely governed by his associations and impressions. The text is trying to “go beyond” language, to give us a sense of Bloom’s emotions, experiences etc. before they reach the level of neatly formulated sentences. The result is that the passage is difficult to read, and there is a lot in it which remains unexplained (just as many of the associations of strangers or friends would remain unexplained for us if we had the miraculous chance to look into their minds the way we are able to look into the minds of fictional characters. CHARACTER AND CHARACTERISATION Kinds of characters flat character: a character that is characterised by one dominant feature. Flat characters appear frequently in comedy (where one feature of a character is often caricaturistically exaggerated), in allegorical texts (e.g. when a character’s sole function is to embody Sin or Temptation), in popular fiction (action heroes and especially their opponents don’t need too much roundness), or whenever characters represent a type (psychological, national, social etc.) rather than an individual. There is no automatic difference of artistic value between flat and round characters; Charles Dickens’s flat characters and caricatures, for instance, are as successful as any round character. round character: a character that is characterised by several features, looking “three-dimensional” stock character: a type of character that reappears in several works of literature/film with always the same features; a character that is always on stock, sitting on the shelf, and writers can simply use them whenever necessary. For instance, commedia dell’arte worked with stock characters, figures that were basically the same in every play (the jealous and greedy husband, the scheming servant, the handsome young suitor, the lecherous priest, etc.); action movies, Westerns and many other kinds of literature and film use a large number of stock characters (e.g. the antagonists of James Bond are very often psychopathic terrorists, never British, who want to rule the world) caricature: an exaggerated, ridiculing portrait of someone (visual or verbal) static character: one that does not change in the course of the action dynamic character: one that changes in the course of the action (e.g. Julien Sorel, Timár Mihály, Ivan Ilyich) protagonist (főszereplő): the main character of a story. “Protagonist” is a neutral term that contains no value judgment: a protagonist might be heroic, wicked or average. This word should be used when discussing the main character of any text, independent of his/her moral features etc. The opposite of protagonist is antagonist or, in another sense, minor character (“mellékszereplő”: in film, minor characters are called “supporting actors/actresses”). antagonist: the enemy of the protagonist, the character who wants to prevent the protagonist from achieving his/her aims. “Antagonist” , like “protagonist”, is a term without value judgment. Thus, if the protagonist is noble and virtuous, the antagonist is immoral and wicked, but if the protagonist happens to be immoral and wicked, the antagonist might be a “good” character. For instance, Antigone’s antagonist is Creon. Not every text features antagonists; for instance, Julien Sorel’s “antagonist” is petty-minded, boring nineteenth-century French society rather than any particular individual, and this society is every now and then embodied in certain individual characters. hero (hős) or heroine (hősnő): a character with heroic features, not necessarily the main character. “Hero” is a word that implies a value judgment: a hero is noble, brave, virtuous, loving, attractive, etc. Nowadays, heroes are more or less extinct from serious literature or film, they appear in romances, adventure stories, action movies etc. (e.g. James Bond or William Wallace Mel Gibson in Braveheart) *ANTIHERO antihero (antihős): a character that lacks heroic features, an ordinary, weak person who is unable to control his life. It is important to note that the antihero is not evil or wicked, simply powerless and helpless, unheroic. Late 19th- and 20th-century literature and film are full of antiheroes. It is important to note that antiheroes are more and more frequently the protagonists of the stories in which they appear (it is symbolic in this sense that in a famous and excellent twentieth-century reworking of Hamlet, Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, the two protagonists are the insignificant and very unheroic (antiheroic) minor characters of the Shakespeare play. Well-known antihero characters include the figure of the chinovnik, the petty office clerk and penpusher in Gogol, the schlemihl (from the German Romantic writer Chamisso’s character Peter Schlemihl, who sold his shadow and wondered aimlessly in the world), the characters of Franz Kafka (Gregor Samsa in “The Metamorphosis” or Josef K. in The Trial), Vladimir and Estragon in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, the protagonist teacher of history (Nyúl Béla) in Fábri Zoltán’s great film Hannibál tanár úr (based on Móra Ferenc’s 1924 novel), or many of the characters played by Woody Allen. Please remember not to confuse antihero with villain, and protagonist with hero. villain: an evil, wicked character. “Villain” is like “hero” in the sense that the word implies a moral evaluation, only in this case negative. Villains tend to appear in stories where there are also heroes. Shakespeare’s Richard III is probably the greatest villain in literature, but most villains appear in romantic and adventure stories (for instance Dr. No and other opponents antagonists of James Bond). A villain in a text without real heroes is Krisztyán Tódor in Jókai’s Az aranyember. Once again: please remember not to confuse antihero with villain, and protagonist with hero. a doppelgänger (German word) or double (“hasonmás”, “alterego”): a figure who is the double or duplication of somebody else, in the sense that the doppelgänger embodies this person’s secret self or secret features. The double is often the product of the repressed desires, anxieties and fears of the person whose secret self it embodies. The most famous double figure is probably Mr Hyde, the brutal murderer, who is the double of the respectable scientist Dr Jekyll (in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and in countless film versions). Famous literary doubles appear in the works of Edgar Allan Poe (e.g. “William Wilson”), Dostoevsky (“The Double” – “A hasonmás”), Vladimir Nabokov (e.g. Despair or Lolita) and Babits Mihály (A gólyakalifa). Successful recent film versions are David Fincher’s film The Fight Club or David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. motivation (indíték, motiváció): that which makes someone act in a certain way. Do not confuse this word with motif (motívum see above) which means something entirely different. action gratuite (French: gratuitous action, unmotivated action; in Hungarian, the French expression is used): an act without motivation; frequent in 20th-century literature and film. For instance, action in the theatre of the absurd tends to be action gratuite, as there is no coherent, continuous self that could be the source and origin of acts, the acts of a character are not really connected or explained by means of being the acts of the same character: something that a character does is not related to what (s)he will do in the next minute. For instance, the acts of Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot tend to be gratuitous, or the murder committed by the narrator Meursault in Albert Camus’s The Stranger (A közöny, 1942), who claims he shot the unknown Arab four times because it was too hot and the sun was too blinding. Characterisation characterisation: presenting/portraying a character. There are two basic ways of presenting a character. a, block characterisation or direct definition: the narrator describes the character for us in one block, including external appearance and psychological features. b, indirect presentation: when a character is revealed gradually in the course of the action and narration. Every element in any work may be an element in indirect characterisation. The most important possibilities are the following: *KINDS OF INDIRECT PRESENTATION OF CHARACTER external appearance: when we can guess the character’s inner traits from his/her external appearance, for instance his/her face. In James Bond films, for instance, it is always very easy to recognise the villain at first sight because he always looks villainous (often a physical disfigurement indicates moral and mental disorder). Certain clichés work powerfully in this logic: fat people are merry and jovial, red-haired women are sensuous and seductive, etc. setting: the places inhabited by characters betray their character (e.g. the opening section of Balzac’s Old Goriot, when the rooms and pieces of clothing of the inhabitants of the Vauquer boarding house are described in detail, obviously because Balzac believes that such information is important and reveals character). action (when a character is revealed through his/her acts) speech (when a character is revealed by what (s)he says and by how (s)he says it, by his/her style, vocabulary, syntax. A character’s use of language reveals the figure’s psychological traits, social standing, etc. For instance, in Hamlet, most characters speak in verse, except the grave-diggers who speak in prose; this is a sign of their low social status. telling names (see below) *TELLING NAMES telling names (beszélő nevek): when the name of a character suggests his/her internal features. Sometimes the name tells all about the character by directly calling attention to his/her most important feature. There are several kinds of telling names. 1, allegorical names: if a figure is called Sin or Goodness in a Christian allegory, nothing else is needed to be known. 2, Another kind of telling name is when the name recalls some mythological, biblical or literary model; for instance the protagonist of Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is called Stephen Dedalus (and like the mythological Dedalus, he wants to fly above his world). The narrator of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is called Ishmael, and Captain Ahab’s name also has a Biblical source. Names in Matrix like Morpheus or Niobe are also telling names in this sense. Biblical or mythological telling names might be more or less ironical. It is not accidental that, in the Agatha Christie novels, Inspector Poirot’s first name is Hercule, that is, Hercules). 3, Sometimes the name becomes a telling name because it indicates a type: in Örkény’s Tóték, for instance, it is important that the family is called Tót, an extremely common name not often chosen for protagonists. The same applies to the main character of Martin Amis’s novel Money (1984) called John Self. 4, Sometimes it is the sound of the name that suggests something about the character: for instance, Akaky Akakiyevich in Gogol’s “The Overcoat” is aptly characterised by his name. 5, Telling names can be ironical, when the character suggested by the name does not match the figure wearing the name. For instance, in Thomas Hardy’s novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles (Egy tiszta nő, 1891), the character Angel Clare is not at all angelic. SETTING setting: the place and time in which the story unfolds. Te setting of most of Mikszáth’s stories and novels, for instance, is the region called Palócföld in the second half of the 19th century. spatial setting (also referred to with the French word locale): the place where the story is set *THE FUNCTIONS OF SPATIAL SETTING it heightens the sense of realism (verisimilitude); the detailed description of a street, landscape, building or an interior creates the effect of faithfulness, reality. Often many elements that are described have no other function apart from creating the sense of reality. For instance, the extremely long description of the Paris sewage system in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables (A nyomorultak) has this function. A special case of this function of spatial setting occurs in what is called couleur locale (French expression, meaning “local colour”, “helyi szín”) Couleur locale is simply a special effect, the inclusion of settings and objects that give the special feel or atmosphere of a particular region. For instance, a film or a book set in the Sahara will usually present a couple of palm trees and camels in order to “prove” its realism; a film set in the English countryside will often include shots of rolling green hills with grazing sheep, half-timbered houses with thatched roofs, etc. characterisation: description of the spatial setting (buildings, rooms, the environment of the character) suggests features of the character with whom the environment is associated. Description of the environment may indicate the social status, occupation, but also the sometimes hidden psychological features of the character (for instance in Gothic fiction). In Edgar Allan Poe’s story “The Fall of the House of Usher”, the crack in the wall of the protagonist’s house suggests his cracked mind; in Angela Carter’s novel The Magic Toyshop, the wooden puppets and the entire house reflect Uncle Philip’s strange mind, but also the young girl Melanie’s sexual fantasies. symbolic dimension: certain archetypal places have symbolic connotations: labyrinths, dark forests, caves have symbolic features that are preserved even in realist fiction or film. For instance, the moors in Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights or the sea in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick are clearly symbolic spaces. atmosphere: this aspect is closely related both to the symbolic dimension and to characterisation. The landscape, the weather, the natural scenery or city scenes often contribute to the momentary mood of the story, to the mood of the main characters. A key term in this respect is pathetic fallacy, an expression coined by the 19th-century English art historian John Ruskin (“pathetic” in this sense means “having to do with emotions”, and “fallacy” means “a mistaken belief”). Pathetic fallacy is the mistaken belief that the natural world (e.g. the weather) reacts to our emotions and reflects our mood. For instance, if we think that the sun is shining because we are happy, or that it is raining because we are depressed, we also fall victim to the pathetic fallacy.