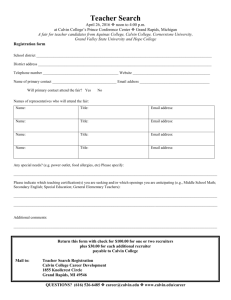

10SenecaCalvin - KEVIN CRAIG for Congress

As we have said, the Reformers' Humanistic training could well have been providentially overruled or utilized in a way harmonious with the Scriptures. But we believe that the training and early environment of the Reformers was not so used, and so we felt justified in examining it. Now we turn to

THE REFORMERS' PAGAN DOCTRINE OF THE STATE

We looked briefly at Calvin's Commentary on Seneca's De dementia, and we shall hear much more of Seneca's influence on Calvin's doctrine of the State. But some may ask how fair it is to attribute to Calvin's career as a Christian reformer those beliefs held while still a Humanist. Of course, there is always an element of speculation present in all of this historical reconstruction.

And only a couple of years ago I myself would have vehemently pooh-poohed any suggestion that

Calvin (of all people!) would have left any Humanist stones unturned in his formulation of a

Christian politique. I am now open to such suggestions both because I now realize that there is much we can learn from the Humanists that is in accord with the Scriptures (and thus much that

Calvin could have learned) and because the evidence seems to indicate that Calvin imbibed far too much of the bad that Humanism had to offer.

The general influence of Seneca on Calvin should be discussed before we look at the specifics of his doctrine of the State. Did Calvin hold on to Seneca's Humanism even after his conversion?

Well, Breen notes that "The contention of some writers (Doumergue, Goguel, et al.) is that he was a Protestant already when in 1531 he was writing the Commentaries on Seneca." 29 But it is not necessary to maintain this position, when Calvin appears to be such-a thorough Senecan even at the height of his career. Balke's opinion is obviously important in this context:

But Calvin always remained the humanist that he was before his conversion. His thorough study of the ancient classic placed a noticable stamp on everything he later wrote. Thus, for instance, many passages in the Institutes clearly echo Calvin's earlier concentration on the classics; his thinking was '•specially influenced by his study of Seneca.

It is clear that some of the elements that appear in the Seneca commentary would continue to be determinative for Calvin's political insights. Calvin very likely borrowed his concept of the organic structure of the state, for example, from his exhaustive study of Seneca's works and thought. Already in this first publication Calvin tried to define the nature of the state. He claimed that the state is a council or gathering of people who are united under law. Starting from this organic analogy, he continued,

If then not every society constitutes a state, but only one which lives by upright morals and fair laws, those who do not obey the laws are not citizens, but are cutjjff.from thejtody of the lawful state.

Here we have a classic basis for Calvin's later program in Geneva, for these are some of the principles that later would guide him in his political concepts and practices)

; It is striking that Calvin's concept of the organic nature of the state even surfaced in a sermon on I Samuel 9 just two years before his death. In his exegesis of the text he gives an extended exposition on the nature of the state that is in complete agreement with his

Seneca commentary.

These tendencies found clear echoes in the passionate lines with which Calvin opened and closed the Institutes as he set forth his political philosophy. Calvin's letter to Francis I devoted the same attention to the nature of the kingly office and the firm rule of established law as we find in his Seneca commentary.

The closing chapter of the Institutes, which forms a literary unit with the letter to Francis I,

29 Breen, 13-14.

reviewed the same classic materials as the treatise written in 1532.. We will give ample attention to these passages and we will discover that it is precisely in these sections that

Calvin is in sharp disagreement with the Anabaptists.

Notwithstanding the powerful transformation that took place in Calvin's life shortly after

1531, the Seneca commentary portrayed an image of an^ajnbjtiojuS young scholar with a deep interest in social and political theory and practice, and with a • great concern for order and authority. Although his spiritual struggles were not yet revealed, the commentary clearly pictures a young man with deep convictions, which would naturally place him in conflict with prevailing Anabaptist ideas.

30

Balke's final remarks presuppose some lawless and rebellious tendencies on the part of the

Anabaptists, and with all those carry-overs from his Humanist education, one wonders what

"powerful transformation" is supposed to have taken place in Calvin's life (of course, Balke believes that Calvin was converl ter writing the Seneca Commentary). Nevertheless, Balke's conclusions are significant.

As we analyze Calvin and speculate on the date of his conversion, we are faced with something of a dilemma. If Calvin was converted at an early date, we are disappointed to find him so engrossed in the writings of the pagans. But if Calvin was converted later in life, we must expect that his earlier education in Humanism would not be so easily removed. Not that God couldn't erase it with dramatic immediacy, but that such is not His normal providence. Breen has recognized this:

It is remarkable that Calvin was converted to radical Protestantism rather late in life. He had been almost entirely committed to the humanistic ideal until his twenty-fourth year.

As a rule young people experience their change before they are eighteen! To have experienced a conversion six years later than that meant much for Calvin, especially since he was unusually precocious. It may be said that at twenty-four he was a seasoned humanist, as a study of the Seneca Commentaries abundantly testifies. Sufficient attention has not been given to this fact. Generally his biographers exlaim over the extreme youth of the writer of the Commentaries, and in a way they are right. But from the point of view of this conversion, the same cannot be said. This, I believe, is of the utmost importance when we consider the precipitate of humanism in his work as a reformer.

The most striking result of this late conversion we can most reasonably expect to appear in what may be called his mental "set." No longer a very young man, and having so thoroughly imbibed the spirit of humanism, his conversion could not possibly negative his acquired habits and attitudes of mind.

31

Let us then examine the mature Reformed doctrine of the State under three heads: the problem of the "one and the many," the problem of Church-State separation, and miscellaneous problems of

Statism. We shall continue to avoid references to "Statism," "Humanism," or "Constantinianism," unless it refers to a specific violation of Biblical Law (recall that the early Reformers were following a fundamental tenet of Humanism when they began to examine the Scriptures more closely).

State and Freedom

Luther's attack on the Church of Rome involved, according to Durant, three central "walls" that the papacy had built around itself: "the distinction between the clergy and the laity, the right of the pope to decide the interpretation of Scripture, and his exclusive right to summon a general council of the Church. All these defensive assumptions, said Luther, must be overthrown." 32 The second wall in particular had always been the impetus to Reformation; the Roman church had long

30 Balke, 22-25. Balke gives an unrelated carry-over on P, 30.5,

31 [28a] Breen, 146.

32 [31] Durant, 352. Durant the Humanist does not see the issue of God's pardon of sin through the

Atonement of Jesus Christ as being of much, significance. Disappointing but not unexpected.

frowned on the "laity" being in possession of their own copy of the Scriptures in their own language. Luther worked hard on his own translation of the New Testament so that "laymen" could search the Scriptures on their own. One could call this "anarchistic" but miss the point that the individuals were removing themselves from under the authority of the State or Church in order to subject themselves more fully to the Word of God.

We are distressed, therefore, to read that the early -Reformers, who held to private as opposed to ecclesiastical judgement of the Scriptures, later changed their tune, and "the principle which the

Reformation had upheld in the youth of its rebellion - the right of private judgement - was as completely rejected by the Protestant leaders as by the Catholics." 33 Particularly, our eyebrows are raised when we read that "Calvin was as thorough as any pope in rejecting individualism of belief; this greatest legislator of Protestantism completely repudiated that principle of private judgment with which the new religion had begun. (In Geneva) a body of learned divines would formulate an authoritative creed; those Genevans who could not accept it would have to seek other habitats.

Heresy again became... treason to the state, and was to be punished with death." 34 Many other writers (Humanist —certainly not Reformed!) have criticized Calvin as an authoritarian dictator.

How fair is this? Did Calvin really despise the judgment of "laymen" and exalt unity of belief under a powerful State?

As a Reconstructionist, I read such accusations and dismissed them as Humanistic falsehoods.

I believed there had to be an explanation for them somewhere. When Willem Balke's book was advertised as the answer that "rehabilitates John Calvin" as against those who opposed him as a tyrant, I anxiously read it. Who would have expected Balke to confirm the charges of the

Humanists?

We have already seen Calvin imbalanced preference for order as against freedom an it manifests in his commentary on Seneca. It is evident his later works as well. The Anabaptists believed that Luke 22:26 forbids Christians from being Statist government officials. They observed that in their day political pressureswere such that one could not hold any office and limit his activity to Biblical or near Biblical behavior (Isaiah 49:23; 60:10), but rather would be compelled to Statist activity. The yconcluded that a Christian could herefore not seek civil office, an argument very much worthy of consideration! Calvin mocked this effort at Christian obedience in hiss

Institutes, as Balke notes:

This leads Calvin to cry out, "0 clever interpreters! CO dex-tros interpretes)." He insists that in this passage government officials are simply not at issue.

35 Typical of Calvin also is the remark, "Obviously it is an idle pastime for men in private life, who are disqualified from deliberating on the organization of any commonwealth, to dispute over what would be the best kind of government." 36

Calvin's study of the pagan political philosophers was making him "increasingly ... concerned with the ... function of the state," as Balke notes.

37 Now one who is favorable to Calvin will think this means Calvin is constructing a "Christian critique" of pagan politics, being concerned to point out the "proper function" of the state (as Balke does). But I can see how those who bore the brunt of Calvin's stinging (and often false) accusations (which we shall examine) would come to think that he was actually after a purple robe for himself! Especially if they read his obsessive references to political and ecclesiastical order. Balke quotes Ganoczy, who says that "the content of De dementia witnesses the thought on society and community of an author who places order near the top of the scale of values." 38 Balke continues:

33 [32] Durant, 456

34 [33] Durant, 473

35 [34] Here is an obvious example of the danger of participating in a home Bible study without the leadership of an accredited Seminary graduate who has studied Seneca. Those crazy Anabaptists read Luke

22:25 ("The kings of the Gentiles exercise lordship...and are called benefactors. But ye shall not be so") and came up with the incredible idea that this verse has reference to (get this) government officials! Anarchists.

36 [35] Balke, 64, my emphasis.

37 [36] Balke, 38.

38 [ 37] Balke, 23n

...the Seneca commentary portrayed an image of an ambitious 39 young scholar with a deep interest insocial and political theory and practice, and with a great concern for order and authority.

40

As a reconstructionist, I learned that an incredible feature of the Age of Gospel Prosperity is the fact that the Law of God is internalized and written on the heart of the believer, and that the

Holy Spirit has been poured out to empower men to new obidience. I also learned that as Christian families begin to obey the Law, the State will recede in power and influence. Is it possible that in the New Testament age, with the help of the Spirit and the Law written on our hearts that we could duplicate the situation that existed in Abraham's day, where there was neither Church nor State? Is this perhaps some kind of "limiting concept," whereby we strive for such obedience among ourselves that political power is unnecessary?

The Anabaptists sensed that the answers to those questions were "yes," although they probably didn't formulate them as I have. In these "Studies in Patriarchy" I am entertaining the idea that obedience should reign so completely in the Family of God that political power is superfluous.

"The kings of the Gentiles" may never recognize their own superfluity, and we continue to obey their every statute (I Pet. 2:13, limited by Acts 5:29). But as a post-millen-nialist, I believe that

"Patriarchies" will one-by-one be established over the earth to an unimaginable extent, independent of both Pope and King, as was the case with Abraham and the thousands who constituted his household.

I am only too willing to admit that it seems far-fetched. But what it signifies most immediately is a direction in which the people of God should be moving. In the Age of the Spirit, shall we be pessimists or optimists? Should we as Christians be lobbying for "stronger States!" or should our personal admonitions be toward stronger families? The Anabaptists chose to focus on the Family, and warned that those who moved in political circles would be sucked up in the pressure to "exercise lordship" instead of to serve. I think they picked up, in a simple and nonspectacular way, the non-political genius of the Scriptures. Calvin called them "stupid." .

Our adversaries 41 claim that there ought to be such great perfaction in the church of God that its government should suffice for law. (cf. I Cor. 6). But they stupidly imagine such a perfection as can never be found in a community of men.

42

Except in Abraham's day, before Christ's Advent and the pouring out of the Spirit.

If Calvin, with his continual advocation of stronger "authority" meant •*•&* the rule of God's

'.

Law in the lives of believers and their households, we couldn't agree more. But it seems that

Calvin always has pol

: tical institutions in mind, as Balke points out by bringing Calvin's original

Latin to our attention .

In every human society (Calvin says) some kind of authority (politia aliqua) is needed in order to maintain mutual peace and unity. 43

Plato would certainly agree with this, having devised a politia (Republic) of his own.

For Calvin, civil order (politica ordinatio) is a necessity as long as we live on earth, although he is willing to grant that civil order would be superfluous if every one were already perfect. In Calvin's view however, the power of sin is too great to even admit the possibility..., since sin can scarcely be stayed as it is, even with the aid of strict laws and the strong arm of authority.

44

39 [38] The details concerning Calvin’s ambitious father were included because Balke and others note

Calvin;s own ambition (cf. also Dowey, 671)

40 [39] Balke, 25

41 [40] Why must they be considered adversaries?!

42 [41] Quoted by Balke, 63n

43 [42] Balke, 62.

44 [43] Balke, 63. More recent Reformed (not necessarily Reconstructionist) writers have observed the superiority of the Family over the State in preserving order and staying lawlessness. We have discussed this

It seems that Calvin feels that the State will bring about Gospel prosperity faster than

"Christian self-government." Anabaptist sympathies toward the Christian community over the

State "touched a very sore spot with Calvin.'" 45

Not surprisingly, "the primary accent in Calvin's ecclesiology falls on unity," 46 as it does with his doctrine of the State.

For the Christian who analyzes politcal thinking in terms of "the one and the many," Calvin's thought is most disturbing.

.. ;

All States as Part of the Body of Christ

•

Nearly all Americans today will profess to hold to the doctrine of the separation of Church and

State. All modern Anabaptists will tell you that this doctrine was handed down to us by the

Anabaptists of the 16th Century, and many Reformed commentators will agree. But it seems that Calvin did not hold to such a separation, and the bulk of his attack against the Anabaptists was directed at them because they did.

We have already mentioned the politicization of the church at the time of the Emperor

Constantine. Verduin speaks of the monumental change that took place:

What happened is that the church as Corpus Christ! (the body of Christ) had given way to

Corpus Christianum (the body of the christened).

47

Under this "corpus christianum," the baptized person is made simultaneously a member of the

Church and the State, (i.e., the church-state). Everybody was a member of "Christendom," and the distinction the Anabaptists demanded between Christians and non-Christians was out of the question. The Reformers followed the Constantinian path; "The Reformation in its final form was continuous with the corpus christianum tradition, whereas Anabaptism was continuous with the

Corpus Christi tradition." 48 The Anabaptists refused to acknowledge that baptism was an ingrafting into the body of the State, they refused to have their children christened, and for this they were tortured (to produce "sound doctrine") and executed. We have already seen how Seneca's doctrine of the organic nature of the State was held by Calvin throughout his career (p. 9.).

Calvin's Glorification of the State

Kings and magistrates, like prophets and teachers, are called and annointed of God to a special task, and are given a special mark of divine election. In fact, Calvin implies, though he never brings himself explicitly to say, that the magistrates are above even the clergy in the sacredness of their office. "Wherefore no doubt ought now to be entertained more fully in other papers. We may note here Dr. B. M. Palmer in a publication of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S., 1876, The Family in its Civil and Churchly Aspects (Reprinted, 1981,

Sprinkle Publications) , who points out that the Family has been so equipped by God that it is far superior to the State in preventing lawlessness .

Quite obviously, the Anabaptists anticipated this Reformed writer by several centuries, and Calvin, arguably because of his saturation with pagan political thought, was unable to grasp the thrust of the

Anabaptists. When they said Christians must not strive for political power he called them revoltionaries, anarchists and pacifists. When they said we should stregthen and edify Christian families and not the State, he called them perfectionists. When they they said the Holy Spirit would empower Christians to take over functions presently mismanaged by the State, he called them spiritualists and enthusiasts. And when they themselves attempted to put a Christian ethic into practice, by serving and sharing with one another in a

Christian community, he called them communists. In all of these conflicts between Calvin and the

Anabaptists, the common denominator is the State, or as we shall see, Calvin's perception of how the State would react if it felt that Calvin was party to Anabaptist thinking.

45 [44] Balke, 290

46 [45] Balke, 49.

47 [46] Leonard Verduin, The Anatomy of a Hybrid, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publ. Co. 1976, p. 104.

All of Part Three,"The Birth of the Hybrid," describes this change in detail.

48 [47] Ibid, p. 158. All of Part Four is a detailing of the Constantinian nature of the Reformers.

by any person that civil magistracy is a calling no only holy and legitimate but by far the most sacred and honorable in human life.

49

Calvin's lack of agreement with the Anabaptists is evident not only in his justification of the right of the government to wage war... (where) the influence of Seneca's De dementia is unmistakable...but also in his passages on the right to levy taxes.... Calvin offers an abbreviated analysis of the attitude of Christians toward taxation...: "tributes and taxes are the lawful revenues of princes, which they may chiefly use to meet the public expenses of their office." These may also be used to provide the splendor that is connected with the worthiness of their office....

50

.

Calvin not only granted legitimacy to those who would call themselves a "State," but denied the applicability of the Mosaic standards as they applied to the State in the Old Testament. Instead he held to "natural law" ascf castigated those who would judge the modern State by the Old

Testament, as Balke notes:

In this chapter about government, Calvin speaks about people "who deny that a commonwealth is duly framed which, neglecting the political system of Moses, is ruled by the common laws of nations." Calvin calls this view dangerous and rebellious 51

Finally, Calvin attacked the Anabaptists for their refusal to put. down their plareshares and pick up swords; their disdain for political lordship annoyed Calvin. Eberhard Arnold notes that the Anabaptists demonstrated again and again that the state existed on the basis of Roman Law, that the republican as well as the imperial states lived according to the imperial law of the Romans, and that therefore the nature of the state was pagan and Roman, not even Old-Testament and Mosaic.

52

— -

Going further, the Anabaptists held, as we have seen, that it is forbidden for a Christian to become a pagan lord over others, but rather is required to serve others. If it is difficult for a Christian

Reconstructionist to get elected to public office and to be able to consistantly put into force the

Scriptures, one can imagine how difficult such a prospect would be in the age of "Divine" monarchies. The Anabaptists were convinced that no Christian could uncompromisingly secure public office. "Calvin sharply condemns this highly spiritual disregard for wordly political maters. He clearly refers to the Anabaptist world-flight by which they refuse to hold a government office and to participate in public life.... He reproves their arrogance.

53 "

49 [48] Harkness, p. 226.

50 [49] Balke, 66-67. Naturally Calvin warns against excess. But he has already opened up two doors to totalitarianism. First, no one has ever shown the Anabaptists where Scripture gives the right for party A to demand from party B money to 1) kill members of party C or 2). provide splendorous symbols of lordship.

(The question of how much, if at all, States should tax is not addressed by those passages which tell

Christians to pay whatever taxes are levied, even taxes levied by evil States as a judgment upon a people lacking in good works.) Second, as we see in the next quote, Calvin denied the abiding validity of the Old

Testament civil law upon civil institutions (see our paper, "Theonomy and the Reformers") dragging his warnings against excess into the mire of subjectivism. After all, who is to say how much splendor is too much if splendor be allowed at all?

51 [50] Balke, 64.

52 [51] Eberhard Arnold, "The History of the Bapizers Movement," Mennonite Quarterly Review, July,

1969. Exerpted in Baptist Reformation Review, Vol. VII, No. 3 (Autumn 1978) p.20. Of course, many

Anabaptists were glad that it wasn't Old Testament standards that governed the State, as they preferred the

New Testament over the Old. But given the standards of the Reformers, the Anabaptists were showing the

Reformers' inconsistancies.

53 [52] Balke, 63

This name-calling 54 was then followed by an incredible•change of tune. Humanists, in an attempt to discredit the Reformation, passed rumers (putting them especially in the ears of powerful monarchs) that the Reformation was anarchistic, and was attempting to diminish the power, influence, economic spoils, in short, all the fun, of being a monarch in the absence of

Biblical Law. Balke says that

»•

These Humanists evidently were strongly opposed to the Reformation and tried to insinuate that the evangelical doctrine had a political character. They knew how to touch the king in his most sensitive area. Without interruption, they persisted in severely condemning the evangelical doctrine, in which they saw a threat to the authority of the church and state.

55 They tried to ascribe a political character to the evangelical doctrine, and thus portray it as a danger to the state.

56

Now, as I understand Reconstructionism, if Reconstructionists could have their way, all oppressive States and omnipotent monarchies would be done away with •— through the best means, of course. I am quite sure, for example, that the Reconstructionists would never, ever call up an anti-Christian dictator and reveal to him the location of secret, underground Bible studies, even if they were being led by Ronald Sider and attended by Evangelicals for Social Action. I would think it understatement to say that Reconstructionists would do everything in their power to decrease the power of a would-be-divine State and would certainly not call upon the power of an absolute monarch to squash non-reconstructionist Christians. If this is the case, then Calvin was no

Reconstructionist. After calling the Anabaptists so many names for failing to be political enough, he then turns around and tells all the great statists of Europe that it is the Anabaptists, not the

Reformers, whose doctrine has politcal character. Calvin dedicated his Institutes to France's

Catholic monarch, Francis I, "to counteract the influence of these (humanist) courtiers" as Balke puts it.

57 Did Calvin have some clever strategy in mind by which he would disarm the king, only to shortly thereafter make a bold, clarion call for the implementation of the Mosaic Civil Law, thereby eliminating a monarch that was already persecuting Protestants? No, Calvin hoped to get on the good side of the dicatator and make Protestantism (instead of Catholicism) the established state religion of France, and simultaneously close down the Anabaptists. Balke observes that

Calvin, who had contacts with the royal court, still hoped that the wavering attitude of

Francis I might turn in favor of the Reformation. In France, where a movement toward absolute monarchy was developing, the attitude of the king would carry decisive weight should he decide in favor of the Reformation.

58

"Decisive weight": what a marvelously political euphemism for the torture and execution of

Anabaptists that was already taking place under the watchful eye of statists like Zwingli and

Melancthon.

59 As Balke points out, the burden of Calvin's politically-minded preface to the

Institutes was directed against the Anabaptists:

In his letter to Francis I Calvin speaks openly about the Anabaptists. He clearly dissociates himself from them, claiming that they are instruments of Satan. He explains that Satan drives people into revolutionary reaction in order to cruelly extinguish the dawning light of truth:

54 [53] And to call the Anabaptists "highly spiritual" or "other-worldly" is just this. It is hardly a concerned effort to communicate with them and come to grips with their ideas.

55 [54] or more accurately, the power of the Church-State

56 [55] Balke, 39, 41

57 [56] Balke, 39.

58 [57] Balke, 41

59 [58] Balke, 42-43.

" (Satan arouses) disagreements and dogmatic contentions through his Catabaptists and other monstrous rascals in order to obscure and at last extinguish the truth." 60

Balke, who knows the difference between the evangelical Anabaptists and the fanatics who were wrongly grouped with the evangelicals, notes the unfair treatment given the Anabaptists:

We know that very strange rumors about the Anabaptists and the Protestants were making the rounds in the French royal court. People were of the opinion that Anabaptists ... had horns and lived in promiscuity.

The manifesto to the German princes was the official expression of the errors, judgments, and slander going on at the court in Paris.

Between 1527 and 1535 hundreds of peace-loving people as well as revolutionary

Anabaptists were tortured, burned alive, beheaded, and drowned.

61

Did Calvin stand in the great prophetic tradition of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and the Old Testament prophets by denouncing the King for listening to such slander and acting so oppressively upon it?

Tragically, it seems Calvin had no such zeal against unGodly rulers. In what appears to be a treacherous and despicable scheme, Calvin played himself and his friends off of the Anabaptists, putting the onus on the Anabaptists in an attempt to gain support for his own movement. This strategy against the Anabaptists will be explored shortly; what has been included here is designed to expose Calvin's view of the State.

ULRICH ZWINGLI'S DOCTRINE OF THE STATE

In the same way we analyzed Calvin we may analyze Zwingli. Like Calvin, Zwingli favored

The State Over Freedom

All too often, the emphasis is on unity as it is to be found in the Church-State, and individual freedom and maturity is scorned. One example is given by Yoder, I who describes the efforts of early Anabaptists to propose a political solution to Zurich's problems. Zwingli had been preaching against the taking of interest, and against the Mass, which he said was blasphemous.

But the city council, who was in charge of the government of the church, would not allow, for example, a Protestant observance of the Lord's Table. The Anabaptists eventually came to the conclusion that they would have to disobey the council and observe the Lord's Table Biblically, thus becoming the first Protestants.

62 But before they broke away, whether it is to their credit or discredit, the Anabaptists tried to play political ball with Zwingli and the council. Yoder describes the plan and Zwingli ' s reaction to it :

In considering the halfheartedness of the council and Zwingli' s unwillingness to move ahead without its support, these disciples (the Anabaptists) concluded that the best way might be to get a sympathetic council elected. Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz seem to have proposed to Zwingli that the friends of the Reformation might constitute something like a political party. They were confident that if Zwingli were to challenge the population of Zurich publicly to take sides for or against the Word of God as he was preaching it, the majority would be on his side. This majority could then elect a properly disposed city

60 [59] Balke, 43

61 [60] FOOTNOTE MISSING

62 [61] FOOTNOTE MISSING

!

council and the Reformation would again move forward with state approval. This proposal met Zwingli half way. It did not ask him to act against the state, nor did it say that the state would have no business carrying out the Reformation as long as it acted according to the Word of God.

63

This would seem to be an acceptable proposal. Yet Zwingli, along with Calvin, could not imagine

Reformation taking place at the initiative of individual Christian families. To preserve the allimportant unity of the Church-State, Reformation had to be dictated by the central State. The

Anabaptist plan should have pleased Zwingli, we would think.

Yet by making the membership of such a "Reformation Party" voluntary, this proposal would in effect have created an independent religious institution and would, therefore, have begun to break the bond between church and state. Zwingli had two objections to this proposal. On the one hand, he was still confident that the council could be trusted to move ahead responsibly, though slowly, with the Reformation program. A more basic reason was his growing fear of the divisive social effects of asking individuals within society to make their own decisions. The result might be Roman Catholic worship in one part of

Zurich and Protestant worship in another, thus destroying the unity of the city and with it of the church. This, in turn, would dishonor God by casting doubt upon his sovereignty and upon the clarity of his reavealed will....

64

This would seem to be the same kind of aristocratic humanism that, according to Balke, characterized Calvin. It can be accounted for by discovering that Zwingli had the same "organic" view of the State that Calvin did, i.e., that it was to be considered a part 'of the body of Christ.

Church and State as a Single Body

Bernd Moeller introduces us to Zwingli's (and Bucer's) view of the State:

It is essential to recognize at once that Zwingli and Bucer were both humanists. The political ideas of Zwingli in particular were certainly influenced by humanist thought. The norhtern humanists had preserved the republican ideal of the early Italian Renaissance.

They were thoroughly conditioned by the idea of publica utilitas as well as by the conception of the state as an organism. Hence, Erasmus, for example, invested the state with religious splendor and incorporated the church within it as an educational institution.

Absolutist ideas were already beginning to dawn. The organic conception of civic life, the readiness to unite the tasks of the church with those of the state in a direct and positive bond, and finally the extremely utilitarian attitude shown in these matters — all of these humanist ideas appear again in Zwingli and Bucer. It remains an open question, of course, to what extent the reformers were dependent on humanism and to what extent they only found their own ideas confirmed and clarified by it.

Let us take note of a remarkable fact: Zwingli and Bucer regarded the republican ideal as a dogna higher than all other considerations. For both of them the constitution of their own city, the system which Zwingli called aristocratia, provided the criterion for judgement.

65

We have already seen something of this "organic" view of the State in Calvin. How did it manifest itself in Zwingli? Moeller describes it:

One of the principal themes in the theology of Zwingli, or at least the one that preoccupied him most profoundly in his last years, was. the problem of how tq form the relationship between^ the congregation of Christians and the civil community.30 In this regard he

63 [62] John H. Yoder, op. cit. , p. 30

64 [63] Idem.

65 [64] Bernd Moeller, Imperial Cities and the Reformation, Philadelphia: Fortress Press,

1972, pp. 83-84.

'

never considered the idea of a community of true believers, i.e., an invisible, true church.21 This idea had once led Luther to propose an ecclesiola in ecclesia, but Zwingli, as far as we know, never dreamed of this possibility..On.the contrary,,Lthis man from

Zurich had in mind the church in its visible form, to which sinners also belonged, and whose membership encompassed .the whole city.

From the beginning of his activity as a reformer, he had felt the need of maintaining the unity of the Christian community and the civil community, which Luther had brought together in a new way by teaching a novel doctrine of the church. At the end of his life

Zwingli succeeded in describing this unity in a magisterial essay.^

23-^Erik Wolf speaks of the "synthetic thought" of Zwingli, "Sozialtheolo-gie," p. 176. In fact, as Wolf has conclusively proved for several areas of Zwingli's theology, the idea of unity was part of the very structure of his' thought. -

Like the other great city-dwelling reformers, Bucer and Calvin, ' Zwingli always pictured human society in terms of a body, an image drawn from antiquity and from primitive

Christianity. He conceived of both the civil community and the church as a living organism composed of many members which worked together in close' relationship. And the civil and ecclesiastical communities formed a- body not only individually but together as ecclesia et

26. ZW-CR 14:419, lines 19 ff. See also the second source cited below in part IV, note 25.

Thus the magistracy was; a member of this body, as Z.win£li insisted against the

Anabaptists. 66

Thus, with the Church and the State unified in a single "body," the state would have an active role in the affairs of the church.

This is why Bucer believed that the magistrates ought to protect the church, persecute heretics, hire preachers, and cooperate in church discipline.

67

Later Zwingli clarified and again emphasized the necessity of cooperation between church admonitions and civil discipline.The church was to discipline its members only when the magistracy failed to do so.

68

If the thought of Walter Mondale appointing your preacher is disturbing, keep in mind that

Bucer 1 s thought was in many respects closer to that of the Anabaptists than was Zwingli's.

69

Bucer always emphasized more strongly than Zwingli the limits of magisterial competence. The State should regulate the external actions of men but should not invade the hearts or faith of its subjects 70

Moeller sums up Zwingli's thought as it pertains to the unity of the church-state over individual growth:

As we are coming to see, the essence of the theological evolution of Zwingli and Bucer was the increasingly clear conception of the church and civic community as one body. It was at just this point that Luther's doctrine seemed most deeply foreign to the mentality of the city. In logically linking the concept of the church to justification by grace alone and by faith alone, he had exploded the unity of the medieval town.

66 [65] Ibid., pp. 75-76.

67 [66] Ibid., p. 79.

68 [67] Ibid., p. 77.

69 [68] And it should be kept in mind that Zwingli was closer to the Anabaptists than Calvin I As

Ray Button points out on p. 153 of Christianity and Civilization, The Failure f American Baptist Culture ,

In part Zwingli was a progenitor of Anabaptism, though not exclusively. He tended to have a

"New Testament only" hermeneutic, which shows up in his view of worship music. Thus, it is easy to see that some of his students would press him for consistency.

70 [69] Moeller, 80

At this point Zwingli and Bucer corrected Luther. By insisting more strongly on ideas of community and organism. . .their thought was much more concerned -with the totality than with the individual.

71

Zwingli's Glorification of the State

Just as the doctrine of the Church-State body had terrible consequences in Calvin in such matters as taxation, Zwingli's high view of the State moved him to State-exalting action. While we might list actions that parallel those of Calvin's, one area of Zwingli's activities provide a striking contrast to the Anabaptists: his willingness to mold the State into a war machine. Will Durant has chronicled Zwingli's war against those who would oppose the Prince of Peace.

72

The Reformation had split Switzerland, with half the cantons favoring Zurich and the Reformation, and the rest hostile. Five cantons formed a Catholic League to suppress all Hussite, Lutheran, and

Zwinglian movements (1524). Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, good man of politics that he was,

"urged all Catholic states to united action, promised his aid, and doubtless hoped to restore the

Hapsburg power in Zwitzerland." Zwingli's first response to these movements was a very good one: he sent missionaries to a Catholic district to proclaim the Reformation. Unfortunately for

Zwingli, the results were about as successful as the Bay of Pigs invasion, and apparently as illmotivated, as Durant hints:

One of these was arrested; friends rescued him, and led a wild crowd that sacked and burned a monastery, and destroyed images in several churches (July 1524). Three of the leaders were executed, and a martial spirit rose on both sides. Erasmus, timid in Basel, was alarmed to see pious worshipers, aroused by their preachers, come out of church "like men possessed, with anger and rage painted on their faces...like warriors animated by their general to some mighty attack." (p. 410)

What kind of exhortations and political advice did Zwingli give to Zurich? It seems to be the exact opposite of everything I as a reconstructionist learned that civil leaders should be doing. As

Durant describes Zwingli's program, I shall state briefly what I thought the reconstructionist position was (readers are invited to correct any misimpressions).

Zwingli, enjoying his new role of war leader, advised Zurich to

(1) increase its army and armaments...

Favorite verses on the escalation of war always seemed to be quick on the lips of reconstructionists (Deut. 17:16; I Sam.

8:11-12). Escalation of war by the state inevitably brings confiscation of property and debasement of the currency.

73

(2) to seek allaince with France...

When threatened with an alliance of anti-

Protestant statists, the Protestant statists seek alliance with the sub-protestant statists. What an amazing repeat of the

71 [70] Moeller, 89

72 [71] Durant, pp. 410ff

73 [72] Ronald J. Sider’s latest book is, surprisingly, highly-recommended. The thrust of his first book,

Rich Christians, was essentially, “the government should do it. The thrust of his latest, Nuclear Holocuast &

Christian Hope, (IVP, 1982) is essentially, "the government should not do it." The first book almost couldn't be good; the second almost can''t be bad. He swallows a little too much anti^nuke propaganda, but his views on national defense and civilian resistance to tyrants are highly thought-provoking .

(3) to build a fire behind Ferdinand by fomenting revolution in Tirol...

events of Ahaz and Isaiah's day, and how appropriate are the prophet's remarks (Is.

7:1-9; 8:9-13).

I get the impression that if you like the CIA you'd love Zwinglian missionaries. See I

Timothy 2:2; I Pet. 2:13-16.-20-

(4) and to promise Thorgau and

Saint-Gall the properties of their monasteries in return for their support.

As we shall come to see in more detail, the Reformers apparently did not see some of the more practical implications of the Eighth Commandment ("Thou shalt not steal") as it pertains to government confiscation of property.

In May 1529, a Protestant missionary from Zurich, attempting to preach in the city of

Schwyz, was burned at the stake. Zwingli persuaded the Zurich Council to declare war.

He drew up the plan of campaign, and led the canton's troops in person. At Kappel...they were stopped by Landemann Aebli of Glarus, who begged an hour's truce while he negotiated with the League. Zwingli suspected treachery and favored immediate advance; he was overruled by...the good sense of the Swiss...and the First Peace of Kappel was signed (June 24, 1529). The terms were a victory for Zwingli: the Catholics cantons agreed to pay an indemnity to Zurich, and to end their alliance with Austria; neither party was to attack the other because of religious differences; and in the "common lands" subject to two or more cantons the people were to decide, by a majority vote, the regulation of their religious life. Zwingli, however, was dissatisfied; he had demanded, and not received, freedom for Protestant preaching in Catholic cantons. He predicted an early rupture of the peace. (411-412)

' i

And perhaps as a self-fulfilling prophecy, the peace lasted twenty-eight months.

On May 15,153 x, an assembly of Zurich and her allies voted to compel the Catholic cantons to allow freedom of preaching in their territory. When the cantons refused,

Zwingli proposedjwar. but his allies preferred an economic blockade. The Catholic cantons, denied all imports, declared war. Again rival armies marched; again ZwingU led the way.and ..carried the.standard; again the armies met at Kappel (October n, 1531)—the

Catholics with 8,000 men, the Protestants with 1,500. This rime they fought. The Catholics won, and Zwingli, aged forty-seven, was among the 500 Zurichers slain. His body was quartered and then burned on a pyre of dung.

28 Luther, hearing of Zwingli's death, pronounced it the judgment of heaven on a heathen, 28 and "a triumph for us." 2T "I wish from my heart," he is reported to have said, "that Zwingli could be saved, but I fear for the contrary, for Christ has said that those who deny Him shall be damned." 28 (p. 413)

It doesn't take a Reconstructionist to know that suppression of free trade is only one form of

Statism that often leads to war.

74

All of this seems to indicate that the Reformers (at least Calvin, Zwingli and Bucer) were infected to a large degree with the Statism that was so prevalent in their day. Statism was basic to the Universities of the day, and was put into practice in every palace and court. It

74 [73] See the non-Christian Ludwig von Mises, Omnipotent Government; The Rise of the

Total State and Total War, N.Y.:Arlington House, 1969.

:

doesn't seem that the Reformers, themselves a part of this educational system and environment 75 provided a prophetic denunciation of this humanism.

We shall shortly see the results of the clash between the urban reformers with their "citified theology" (stadisch Theologie •— Moeller) and the non-statist Anabaptists.

75 [74] It may be appropriate here to note the effects of Zwingli's environment upon his theology.

Bernd Moeller has suggested that his urban environment shaped his theology:

Zwingli's and Bucer's views of the state (and also those of Calvin) were obviously determined in large measure by their citizenship in free cities and by their profound, attachment to the urban structure. In addition, it is possible that humanism and many other forces affected them: Zwingli, who, of course, was not a burgher by birth, was influenced perhaps by the Swiss environment in general....

From their ties with civic life and thought we can understand why both Zwingli and Bucer were deeply involved in politics. For them life as a theologian and churchamn was inseparably bound up with life as a citizen. It is not just a symptom of their temperament that they plunged actively into the internal and external affairs of their cities and from that arena became involved in high politics. How carefully

Zwingli the strategist planned and furthered the spread of the Reformation in Switzerland and southern

Germany! How skillfully Bucer politically maneuvered the compromise in the fight over the Lord's

Supper! It was characteristic and appropriate that Philip of Hesse carried on his famous and highly politica correspondence with precisely these two theologians from free cities and not with Luther, who could even say, "It would be more godly to increase agriculture and decrease commerce." (Moeller, 85-

87)