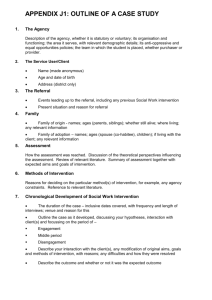

resource manual

advertisement