Remuneration policies of SOEs taking into account

SOE Remuneration and Wage Gap analysis

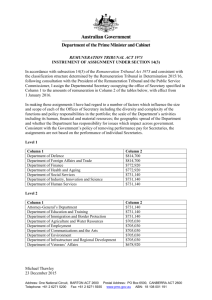

Version: 5 Date:

9 March 2012

Document Name: SOE Remuneration and Wage Gap analysis

Document Author/Owner: Deon Crafford

Owner Team:

Electronic Location:

SMOE

Description of Content:

Position paper as part of meeting the requirements of the Terms of Reference

Approval Status (tick relevant option)

1: Full Approval 2: Partial Approval 3: Conditional Approval

For 2 and 3, describe the exclusions, criteria, and dates of conditions

Document Sign-off Name

Deon Crafford

Dr. Simo Lushaba

DOCUMENT CONTROL INFORMATION

Effective from

Version Number

Amendment Details

&

12/12/2011 Origination of document

26/02/2012 Draft report 1

29/02/2012 Draft report 2

09/03/2012 Finalisation of report

Position/Work Stream Role

PRC Member/ SMOE Work-stream

Date Signed

Chairperson

PRC Member

Nature of the

Change

Info

Data

Data

Amended By

D Crafford

D Crafford

D Crafford

Reviewed By

S Lushaba

PMO team

SMOE team

Approved By

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.

Introduction and problem statement ............................................................................................ 7

2.

Key objectives of the study and method employed ...................................................................... 9

2.1.

Objectives ................................................................................................................................................... 9

2.2.

Method employed ..................................................................................................................................... 10

3.

Effect of state sponsored reviews of SOE remuneration practices and frameworks .................. 11

3.1.

DPE Remuneration Guidelines for State Owned Enterprises (DPE, 2007) ............................................. 11

3.2.

The DPE commissioned Remuneration Review for State Owned Enterprises (DPE, 2010) ................... 12

3.3.

Water Affairs Remuneration Review (DWA, 2011) .................................................................................. 14

3.4.

National Treasury’s review of SOE remuneration (National Treasury, 2010) .......................................... 15

4.

Other key contributions to the question of SOE executive remuneration ................................... 17

4.1.

Labour Union inputs .................................................................................................................................. 17

4.2.

PWC Directors remuneration (PWC, 2010) ............................................................................................. 18

4.3.

Views expressed by SOE boards, executives and middle management. ................................................ 19

4.4.

International perspectives on SOE remuneration ..................................................................................... 20

5.

SOE remuneration and private sector benchmarks ................................................................... 23

6.

SOE Taxonomy model for remuneration ................................................................................... 28

7.

Wage contributions to inequality ................................................................................................ 33

8.

Consolidated findings ................................................................................................................ 41

8.1.

No standard implementation of guidelines for determining SOE remuneration ....................................... 41

8.2.

Parity between SOEs and private sector .................................................................................................. 41

8.3.

SOEs rate high in terms of income equality ............................................................................................. 41

8.4.

Sustainability of SOE income equality is questionable ............................................................................. 41

8.5.

SOE remuneration is highly inconsistent .................................................................................................. 41

8.6.

No common mechanism or tool to consider sizing and other factors influencing pay points ................... 42

8.7.

Lack of a centralised authority to manage SOE remuneration ................................................................. 42

8.8.

Inequality in SOEs are driven by underpaid operatives and overpaid executives ................................... 42

8.9.

Oversight and accountability issues ......................................................................................................... 42

8.10.

Inequality is a growing scourge in South Africa ..................................................................................... 42

9.

Recommendations on management of remuneration ................................................................ 43

9.1.

Establisment of a Central Remuneration Authority (CRA) ....................................................................... 43

9.2.

The adoption of a properly researched Sizing and Positioning Model that allows for granular analysis and differentiation in SOE remuneration ............................................................................................... 43

9.3.

Review and recalibration of SOE remuneration ....................................................................................... 43

9.4.

Stronger education and transparency in SOE remuneration .................................................................... 44

9.5.

Deliberate strategies to address inequality ............................................................................................... 44

9.6.

Extensive board re-education and enablement ........................................................................................ 44

9.7.

Regular formal benchmarking cycles ....................................................................................................... 45

10.

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................. 46

11.

References .............................................................................................................................. 47

INDEX OF GRAPHS, TABLES AND FIGURES

Number Title

Table 1 Inconsistencies in remuneration to the median as per DPE guidelines

Page

10

Graph 1 SOE remuneration benchmarked against private sector 20

Graph 2 Upper and lower ranges of pay below management – SOE to private sector

21

Graph 3 Upper and lower ranges of pay below management – SOE to private sector

21

Table 2 SOE comparative pay ratio to private sector

– per job level

22

Table 3 Comparative pay ratios of sample SOEs to private sector and

SOE median

22

Table 4 Application of taxonomy to SOE sample 26

Table 5 Pay progression between company sizes in SOEs

– A to D levels

27

Figure 1 A categorization of State Owned Entities

Figure 2 Gini Coefficient in the world

29

30

Table 6 Gini Coefficient by country 31

Graph 4 Cumulative percentage increases by job grades 2006-2012 for

SOEs

33

Graph 5 Population versus Gini Coefficient intersect 33

Graph 6 Consolidated remuneration entropy for State Owned Entities

Graph 7 Continued ratio of inequality – lower and upper levels

34

35

Graph 8 SOE/Government remuneration comparisons with private sector

36

Graph 9 SOE skills employed versus skills of the unemployed 37

Graph 10 Pay against organization size standard – Category 8 – SA

Reserve Bank

37

1. INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM STATEMENT

Regardless of where one goes in the world, the remuneration policies and practices of private and state owned enterprises remain emotive issues. The debate around remuneration often hinges on the perceived value added by the incumbent executives, managers or professionals. The perceived value is to a large degree influenced by the vantage point from which it is considered. As the world economy struggles to come to terms with the credit crises and meltdown witnessed around 2008, the issue of executive remuneration has been placed even more in the spotlight. This has been especially true concerning those private entities in Europe and the United States of America that had to be bailed out by their respective governments, effectively placing them under curatorship, if not ownership, of the state. Still there seems to be no end to excessive executive pay and bonus measures.

Organised labour often expresses dissatisfaction at the inconsistencies in bargaining unit remuneration management versus that of executive management. This issue is reflected on in this report. This dissatisfaction leads to increased industrial restlessness and culminates in protests, “go-slows” and full-blown strikes that in turn leads to lost days and declining productivity.

Economists, analysts and politicians constantly lament the poor levels of labour productivity in South Africa. This year, labour productivity (i.e. labour's unique contribution, separating out the productivity that is rightly attributable to capital equipment and machinery) fell to the lowest level in 40 years. Currently, labour's share of national income (i.e. wages as a percentage of total factor income) is at a 50-year low. Over the past three years, wages have risen by 11.5% per annum on average - treble the consumer inflation rate over the period.

Growing numbers of employers are using automation, mechanisation and other laboursaving methods as an alternative to labour, with the result that the economy's capital intensity has risen sharply (Sharp, 2011.) Industry leaders keep indicating that the country is losing out on a window of opportunity to become a more powerful economic player in the world. This is true especially as far as it’s membership of the BRICS group of countries, where labour productivity to cost ratios are considerably more positive, It holds that a continuation of the unequal treatment of labour when compared to that of management, may then be contributing to another negative trend – sliding productivity.

The World Bank considered various studies regarding inequality.and in 2005 concluded:

“ The main message is that equity is complementary, in some fundamental respects, to the pursuit of long-term prosperity. Institutions and policies that promote a level playing field . . . contribute to sustainable growth and development.

” (21 st Century, 2012).

In the light of the above, the Presidential Review Committee for State Owned Entities (PRC), in its terms of reference, was tasked to investigate:

the approach to remuneration in SOEs

the issues surrounding the wage gap or differential

how SOEs should respond to the above

The PRC took note of a number of different investigations into this issue and of submissions made to parliament by other state departments, including DPE and National Treasury.

The PRC was to investigate this matter from an independent position. It needed to determine:

(1) Whether the approach to remuneration in SOEs was based on some degree of standardization and whether it followed the guidelines provided by other

State Departments;

(2) Whether the levels of remuneration paid in SOEs were consistent with the

value offered to the shareholder and ultimately the taxpayer;

(3) Whether SOEs were contributing to a widening wage gap or attempting to reverse the trend and

(4) Whether the performance of SOEs serve a key driver for remuneration.

The performance of SOEs are constantly under public scrutiny, not only because they often deliver services directly to the taxpayer, but also because taxpayers rightly have the perception that they are indirect shareholders since much of the funding and equity in SOEs flow directly from the tax base of the country. SOEs are therefore accountable to the taxpayer through the taxpayer representative, the executive minister providing oversight.

Government owns SOEs also to use these as instruments for addressing the development needs of the country. If they were found to be flawed in, inter alia, the area of remuneration in relation to performance, government stands to be discredited. Proper functioning SOEs with proper management (and remuneration) practices in place are critical to the perception of the state as servant of the people who elected it into power.

2. KEY OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY AND METHOD EMPLOYED

2.1. Objectives

The Strategic Management and Operational Effectiveness (SMOE) workstream interpreted the TOR on remumeration as based on a number of key assumptions. Related questions needed to be answered as evidence to the assumptions. These are:

Assumption 1: Shareholders guide the remuneration policies of SOEs, based on national policy.

What guides the remuneration policy / remuneration governance framework within SOEs?

What are the factors that guide remuneration in SOEs?

What are the elements of the remuneration policy?

Do the guidelines include how often SOEs benchmark remuneration? If yes, against whom and how often?

Is there a rationale for establishing a national oversight structure on SOE remuneration?

Is there a central oversight structure to regulate introduction of emerging remuneration practices?

Assumption 2: Boards formulate remuneration policies in line with the shareholder remuneration guidelines.

What is the role of the shareholder and the Board in formulating remuneration policies?

Do boards enforce remuneration policy and account for any deviations, particularly those out of line with with the Shareholders’ requirements?

Assumption 3: The wage differentials in SOEs are comparable to relevant SA market sectors?

What are the wage income differentials within the SOEs and how do these differentials compare to the local market?

What is the differential index between the top 10 paid and bottom 10 paid employees in an entity?

Are there other measures to report on the wage differential?

Are there wage differential guidelines for remuneration practices on pay structures within the SOEs and do these guidelines compare to the private sector/industry, public service and sectors?

Assumption 4: SOEs remunerate executives and employees at levels comparable to relevant SA market sectors?

Do remuneration practices and packages in SOEs compare to their counterparts in the public service and private sector?

How do remuneration practices and packages in SOEs compare to their counterparts in the developing countries (e.g. BRIC and OECD )?

Assumption 5: SOE’s executives’ and employees’ total remuneration packages are commensurate with the SOE’s performance against its agreed set targets.

What performance measures do SOEs reward when they pay incentives? Are these aligned to achievements towards government policy objectives and mandates?

Do the SOEs’ executives sign performance agreements with the Board and are remuneration packages linked to the performance agreements ?

What percentage of the remuneration package is variable due to performance reward?

While most of these questions are answered in the report, there are some areas where the availability of information was not sufficient to allow for an authoritative perspective. One of these areas are in the linking of remuneration to performance. There is a perception that

SOEs are not performing to the expected standard. This is evidenced in feedback from customers and the SOE middle management level as well as in the unachieved objectives.

Many of these objectives are strongly tied to the mandate of the entity. With this view of performance the extradordinary levels of remuneration creates an even more distorted picture..

2.2. Method employed

The method employed by SMOE to cover this TOR included the following:

Idetifying the key outputs of the TOR;

Gathering and analysing existing data on remuneration practices and frameworks in SOEs;

Asking SOEs for their perspectives on remuneration;

Commissioning primary research and statistical analysis on remuneration data of

SOEs to determine key parameters and trends ….. statement too vague.

Commissioning the development of an economic perspective on the prevailing wage differentials in SOEs as compared to the broader market.

Deriving critical findings as far as SOE remuneration practices and metrics are concerned.

Concluding with recommendations on how the matter of SOE remuneration could be approached in future.

(Note: SMOE focused mainly on the remuneration of executives and operatives in the SOEs and not on board remuneration practices as these were seen to fall within the scope of the

Governance and Ownership work stream)

3. EFFECT OF STATE SPONSORED REVIEWS OF SOE

REMUNERATION PRACTICES AND FRAMEWORKS

The issue of SOE remuneration has prompted a number of reviews by Executive Oversight

Departments, especially the Department of Public Enterprises (DPE), as it has oversight over the key commercial enterprises. It appears though that the main focus of the remumeration reviews has been on the more commercially positioned entities and that the large number of state owned entities (numbering almost 600) has not been served by a standardised approach or framework for remuneration.

3.1. DPE Remuneration Guidelines for State Owned Enterprises (DPE, 2007)

In 2007 the Department of Public Enterprises issued guidelines for SOE remuneration based on market data sourced from 600 South African companies. In this they distinguised four broad bands within which SOEs could fall – predominantly based on size as determined by assets and revenue generated.

These four bands included:

Very Large SOEs (> R 16bn in assets; > R 2.5bn in revenue)

Large SOEs (>R1.55bn; >R243m)

Medium SOEs (>R143m; >R22.8m)

Small SOEs (<R143m; <R 22.8m).

The headlines of these guidelines are as follows:

Guaranteed executive pay, short term incentives and long term incentives are not to exceed the median of the model developed by DPE – the median remains the threshold throughout

Boards have to seek approval for not adhering to the above and have to develop a strong motivation for such

The shareholder has to agree in writing that the pay of executives adhere to these guidelines

Full disclosure of all components of executive pay shall be done in accordance with the Companies Act, the PFMA and King Code for Corporate Governance

Total value of short term and long term incentives shall not exceed 125% of guaranteed pay in a year for CEOs and 85% for other executives

The Execu-measure guideline to be applied takes into consideration: o Company/entity size o Strategic level at which executive is expected to operate o Direct/indirect impact level that the executive has on company results o Complexity of role and problem solving required from the executive

The role of the remuneration committee is clearly spelt out, inter alia, to ensure that there is a clear and direct link between remuneration and contribution to performance, that the shareholder is fully informed on remuneration policies applied (including management of deviations from the guidelines) and that the contracts with executives ensure that SOEs would not be at risk to pay in the event of executive failure.

These guidelines are quite detailed and seem to be supported by strong research and analysis. The determination of pay points

– monetary level at which the person is remunerated per job level - is multi-dimensional; the dimensions used appear to not all

adhere to the same level of detail to enable proper discrimination of a role. The shortfall of these guidelines are that they are predominantly focused on those SOEs that report into

DPE. However, they are not applicable to by far the largest component of SOEs. As reported in section 3.2 the guidelines have not been complied to at the levels the shareholder have demanded. This report will show that the remuneration practices and pay-points have deviated significantly from what is indicated in these guidelines.

3.2. The DPE commissioned Remuneration Review for State Owned

Enterprises (DPE, 2010)

This Review was commissioned by DPE in 2010 and had as primary objective to ascertain the degree of compliance of SOE remuneration practices with the DPE guidelines as referred to in 3.1 above. Secondary to this objective, the review was also to assess the remuneration practices of SOEs against the general market practice and to determine if compliance was satisfactory. If compliance was found to be unsatisfactory, the reason for this was to be determined. unsatisfactory, why this was the case.

The headline findings of this review were:

SOEs do not follow the DPE guidelines issued in 2007 and updated in 2009.

The SOE remuneration practices are aligned to what happens in the general market.

The non-compliance largely pertains to guaranteed or base pay. There is more compliance on the incentive scheme.

Although short- and long-term incentives are aligned to the guidelines, there is a lack of substantiating evidence to prove that payments are matched to achievements.

There is a significant lack of standardisation in the way remuneration is determined (some using guidelines, others not). The approval process followed and the structuring of the remuneration packages also lack standardisation.

Employment contracts for CEOs and executives do not comply with the Basic

Conditions of Employment Act in terms of detailing work, job descriptions, job specifications, job outputs and benefit components.

The Review found that some of the main reasons of non-compliance with the guidelines can be traced back to inadequate differentiation between SOEs. Broad categories are used to differentiate between SOEs which lead to SOEs clustered together that are not similar.

These dissimilar SOEs are then treated as if the same. Data frequency and quality in underpinning the model also presented a problem. It was furthermore concluded that there is a misalignment between the remuneration of board and committee members and the accountability and risk these members faced. This made it difficult for SOEs to attract strong board members.

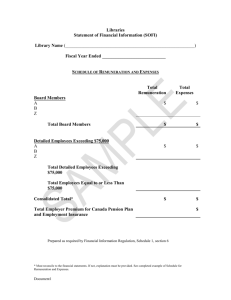

Some of the guaranteed pay discrepancies are indicated in the table below:

Table1. Inconsistencies in remuneration to median as per guidelines (DPE, 2010)

State Owned Enterprise

(DPE oversight)

Executive remuneration %

ABOVE median

Executive remuneration %

BELOW median

Alexkor

Aventura

Denel

Eskom

66%

15%

8%

31%

State Owned Enterprise

(DPE oversight)

Executive remuneration %

ABOVE median

Executive remuneration %

BELOW median

Infraco

PBMR

SA Express

26%

10%

8%

SA Airways

Safcol

18%

27%

What this clearly indicates is that even in a small population of SOEs (those reporting into

DPE at the time), the inconsistency in remuneration is significant. The review furthermore engaged a broad base of specialist stakeholders and derived from their feedback the following:

The role of SOEs in the development of the economy and the country and the fact that the SOEs executives are effectively leveraging taxpayer contributions should be blended together to produce a realistic remuneration framework to attract the right people.

Remuneration should be calculated in a formal, transparent and coherent manner to ensure the shareholders ‘ interests (also taxpayers’) are protected.

Remuneration packages should not create perverse incentives ie. huge short term driven pay-outs where performance and achievements do not align with monies paid.

The monopolistic nature of many of the entities should be brought into consideration to ensure that profitability is not the predominant measure. Internal efficiencies should also receive its rightful focus as it shows the responsible application of the taxpayer’s contribution to the state.

Workers cannot be expected to earn increases on productivity when it is not a determinant that applies to executives.

All staff members (executives included) must be subject to the same disciplinary procedures ie no golden handshakes to get rid of poor performing executives.

The private sector cannot be used as an appropriate benchmarking model for

SOE remuneration because it is in this sector where the skills are to be sourced for ……. The recruitment approach should focus on a different kind of professional who is motivated not by excessive pay-packages but by the ability to contribute to nation building and development.

Remuneration committees must apply a much stronger degree of discretion in evaluating and putting forward executive remuneration proposals.

The boards and remuneration committees must ensure a proper risk sensitive approach in setting remuneration. These committees should also ensure that claw-back mechanisms are in place to recoup monies paid to executives based on unsubstantiated performance which later proves not to be a fair reflection .

This Review underlines the problem of inconsistency in the remuneration of SOEs and has as a major recommendation the establishment of a permanent advisory committee on remuneration within the ambit of the Department of Public Enterprises to address this problem. It furthermore highlights a problem with the executive oversight role of state departments with SOEs. This problem can briefly be stated as if in the context of a small

population of SOEs (nine) which falls under Department of Public Enterprises, the compliance with guidelines is as inconsistent as it is, it points to a low degree of monitoring and evaluation – either contributed by the lack of capacity, or by ignorance.

3.3. Water Affairs Remuneration Review (DWA, 2011)

In July 2011 the Department of Water Affairs (DWA) issued a Remuneration Policy

Framework for Water Board Chief Executives. This had its origins in 1998 and had now been developed to the point where clear principles and agreements about remuneration could be communicated. The clear motivation for this protracted review process was to ensure that

Water Boards were able to attract and retain Chief Executives (CEs) with the capability of managing the Water Board as a company where costs were budgeted for and covered by income. Any excess could then either be offset against future cost increases. It could also be earmarked for use in capital projects to refurbish or enhance the assets required to ensure the sustainable uninterrupted supply of water to communities and industry. This also had to permeate to General Manager (GM) level technical people as the Public Service linked remuneration was not strong enough to ensure retention of critical skills.

The headlines from this Policy Framework include:

The need for central involvement in setting remuneration levels for CEs, especially as indicated by the Minister of Water Affairs approving remuneration levels which the board may have recommended.

The requirement for a common set of standards and centralised set of available remuneration data (through ongoing market surveys) to enable the minister to give appropriate approvals

A proper organisation and job sizing approach using recognised grading systems

(eg. Hay) to justify decision making

Ongoing benchmarking and comparisons to relevant market or industry grouping

Currently benchmarking is done against a mixture of companies which include: state-owned enterprises, tribunals, government-linked entities, and provincial- and municipal-linked entities.

Annual Ministerial recommendations for CE remuneration bands – per Water

Board

The overriding principle to be applied that if the Water Board cannot through its financial parameters afford the payment of the recommended salary then it shall not be paid and the Minister should be notified of the situation

The Board of the Water Board has the responsibility to implement the recommendations of the Minister for CEs. These recommendations apply to CEs who have met all the expectations for the year and are already on the appropriate pay scales.

Where the Board is of the opinion that the performance of the CE - above the requirements of the job - warrants a remuneration adjustment that falls outside that of the Minis ter’s recommendation, such motivation shall then be made to the

Minister. The Minister will apply his/her discretionary powers to ratify such an adjustment.

Should a Water Board for whatever reason change in size or complexity to such an extent that the role requirements of the incumbent will significantly change, the

Board can then motivate to the Minister why a remuneration adjustment is recommended.

The essence of what this DWA remuneration policy entails is that there is a central authority

– in this case the Minister of Water Affairs - that applies a proper process of evaluation and setting principles and standards on which to base remuneration. The private sector is not used as a benchmark for setting remuneration. This practice is different to other

commercially orientated SOEs, but may already have led to higher executive turn-over. This remuneration practice calls for a strong shareholder oversight role to ensure appropriate and acceptable remuneration numbers for these particular SOEs.

In further personal engagement with officials of the DWA it was ascertained that Water

Boards CEOs had not received increases in salaries over the past two years due to the absence of the proper remuneration policy. Furthermore, they expressed a discomfort in having to deal with the increases in terms of the necessary knowledge of remuneration practices and was keen to refer this to DPE. It indicates that despite the strong efforts of the

Department to bring some standardisation, the quality of implementation was still curtailing the effectiveness of the strategy. Institutional oversight capacity and capability still does not match up to the strategic intent of what the Department wishes to achieve.

3.4. National Treasury’s review of SOE remuneration (National Treasury,

2010)

In September 2010 National Treasury released a review of Board and Executive

Remuneration of Schedule 1, 2, 3A and 3B entities (as per PFMA). This review was presented to the PRC in the form of a presentation and contains telling information about the inconsistencies of especially executive remuneration in SOEs.

Notable findings from this study include (the period under review being 2007

– 2010):

Under Constitutional Entities (Schedule 1) there are anomalies of remuneration increases at CEO level of more than 100% in one year at the Human Rights

Commission (R 750k to R 1.6m) and more than 90% at ICASA over the last two years (R820k to R1.55m). However, t he IEC Chief Executive’s pay remained virtually the same in this period.

Under Major Public Entities (Schedule 2) two extraordinary remuneration jumps are notable. At Transnet the CE ’s total remuneration went from R11m to R19m and back to R11m in the last three years. In the same period SAA CE total remuneration went from R7m to R14m and then back to R 4m. What is not clear is why these fluctuations occurred, with the possibility that this was related to the personalities appointed.

Under National Public Entities the Road Accident Fund (RAF) over the last four years saw CEO salary increases from R3.5m to R 7.6m (more than 100%); at

SARS it went from R2.8m to R4.8m (71%) and at the National Home Builders

Registration Council (NHBRC) it went from R1.7m to R4m. At their Chief

Executive pay levels the RAF and NHBRC are way ahead of the rest of the entities in their group where the average CE remuneration is R1.5m. (It is worth noting that all the entities mentioned here collects funds, but that SARS is effectively the only one that does so actively while the others collect through levies and taxes, thus passively – and yet they pay exorbitantly higher CEO salaries).

The base pay (salary alone) at Major Public Entities range between R2m and

R4m, whilst at National Public Entities it ranges from R1m to R4m. At National

Business Enterprises it ranges between R700k and R3.1m. The rest is made up of bonuses, expenses and a category called other.

At National Business Enterprises the CSIR CE pay has increased from R2.8m to

R4.7m in the last four years; at Sentech from R1.6m to R4.6m and at the PIC from R2.6m to R3.8m. These increases vary between 46% and 187%. It is very difficult to explain such varying degrees of remuneration increases when there are no apparent reasons for such extraordinary movements. It should be noted

that this includes base pay, bonus, expenses and a category called ‘other’’. It is thus the total package.

National Treasury has suggested that the remuneration of CEs of State Owned

Entities should be:

Based on the Public Service salary structure

Should have a 5% of package short term incentive

Should have maximum 50% of package long term incentive (once in three years and twice in 5 years)

Should allow for cost of living adjustments.

Clearly these numbers show that there is something drastically wrong in the way the remuneration of SOEs are determined – either by their boards or by their executive authorities. National Treasury makes some recommendations as a counter to this situation including taking public sector remuneration as a broader guideline, but this may be counter again to finding suitable professionals for commercial entities. There are further anomalies in that whilst Treasury is promoting stronger alignment with Public Sector pay scales it clearly has stood by the increase allocated to SARS of 71% in four years – raising the CE pay to R

4.8m. This inconsistency does not help the credibility of the Treasury suggestions.

Eskom and Transnet are two entities that are equally critical to the economy and development of the country. However, the Transnet CEO earns double that of the Eskom

CEO. .

4. OTHER KEY CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE QUESTION OF SOE

EXECUTIVE REMUNERATION

As has been stated before the issue of SOE executive remuneration is an emotive issue and has elicited various contributions from a number of different stakeholders. These are briefly summarised below:

4.1. Labour Union inputs

According to a study undertaken by Solidarity in July 2010, CE remuneration in SOEs make up 1.7% of total profit while the average for all companies in the market is 0.6%. The incentive portion of CE pay is at 53%, that is 3% higher than the average for all companies.

Solidarity also found that the average CEO remuneration of all companies is 38.5 times that of the average worker in South Africa. T he CEO’s of SOEs earn on average 43.9 times more than the country’s average worker. Solidarity concluded that these excesses are contributing to inequality as predicated by the Gini coefficient.

At these high incentive rates there needs to be very clear indications of how a CE has contributed to the success or profits of an entity. More often than not this is not the case.

CEs often get handsomely rewarded for something all employees contributed to. Solidarity argues for a more equal distribution of the incentives amongst all levels of employees for achieving certain targets. They furthermore believe that there should be a direct link between the basic CEO pay and the pay of the lowest paid salaried employee. This is to avoid exorbitant increases at the executive level while labour has to endure with inflationary increases, if that much.

In a strongly worded memorandum to Eskom, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) raised its frustrations about the way in which Eskom was going about the issue of remuneration. It stated that Eskom seeks to implement multi-year wage agreements with labour and is attempting to do so unilaterally; the practice of exorbitant increases in executive pay continues unabated. The lack of transparency in remuneration decisions is particularly frustrating. For instance, as soon as a 9% increase for labour was concluded,

Eskom executives were awarded considerable increases and incentives. They further lament the practice of “phantom shares” for long term incentives of executives – a practice which they believe makes no sense in a state-owned entity and to which the ordinary worker has no access (e.g. as with ESOP schemes in mining houses like Kumba and Impala).

The general impression gained from the NUM memorandum is of two different treatments for two different classes of employees, resulting in an ever-increasing wage gap (in this memorandum reported as 1 to 85 – worker to executive). From a labour point of view uncontained executive remuneration is igniting growing dissatisfaction and militancy.

In view of some of the increases and numbers mentioned in the review of National Treasury above, the position of the labour organisations is stated There are clear indications that the system of remunerating SOEs and their executives is out of control. As will be shown later in this report, SOEs do tend to pay above the market in just about all job categories and there is a strong sense of this not being sustainable. However, as will furthermore be shown, increasingly the major contributor to this “practice of unsustainability” is the ever growing increases in especially executive pay. This means that every other category needs to catch up. Furthermore, it appears that the huge bonus allocations made to CEs and their executives are indicative of the monopolising of performance as if the rest of the staff

(including labour) made no contribution to the performance.

4.2. PWC Directors remuneration (PWC, 2010)

PWC issued the results of a study of executive remuneration in 2010 from which it became apparent that the remuneration levels of executives throughout the market was starting to move further and further away from the lowest level workers and so ensuring an ever widening wage gap. They determined that the remuneration paid to executive directors of large-cap JSE listed companies at a median level was around R 10m per annum – R4m base pay; R2m average performance bonus and R4m average share plan benefits.

Compared to this lowest paid workers were paid R 42 000 per annum – a wage differential in the order of 1:250/300. This is an absolute comparison of highest paid versus lowest paid and not the best way of expressing the measure of inequality. A more acceptable measure of taking CEO pay against the median of all those under the CEO, appear to be more useful and is also more widely used (21 st Century).

But it is in this environment of perceived severe inequality and high executive pay, that SOE remuneration frameworks, policies and practices are established. SOE executives (PRC round tables) justify their high pay by stating that “we compete in the same market for skills” .

According to PWC SOE executive remuneration has also become increasingly more in the spotlight as large severance packages are paid out to underperforming executives and serving executives in underperforming entities continue to receive large increases and bonuses. One of the main reasons for this increased public interest is that the taxpayer rightfully believes the SOE executive and board has some accountability to him/her as the assets and liabilities of the SOE are state funded or underwritten.

The added interest has come from SOE executives in many cases being paid above similar roles in the private sector. A general impression exists that it should at least be market aligned and should go hand in hand with much greater accountability. According to the PWC report, government has taken a stronger look at remuneration through the establishment of a panel of review. This has been criticised by Mervyn King (Convener, King III - Code of

Governance Principles), who believes that this is interference in board duties and that boards are sufficiently equipped to address the matter of remuneration responsibly.

This view may very well indicate the level of misperception that exists around SOEs – often seen as only those large entities like Transnet and Eskom. If the critics of the government’s intervention into remuneration took a more informed look at the SOE remuneration environment, they may conclude that there are many boards who have apparently lost their way in dealing with the issues of executive remuneration. The reasons why this happens should also be dealt with and accountability should be allocated, especially if it relates to poor fiduciary duties or inappropriate motivations. The Congress of South African Trade

Unions (COSATU) has welcomed the establishment of a forum that will recommend a more appropriate and morally acceptable management of executive remuneration. It is fair to expect that remuneration should be commensurate with value add or contribution of the individual to the effectiveness of the SOE. From the indications provided by PWC and assuming that SOEs have themselves fallen trap to what is witnessed in the overall market, a strong intervention is required to bring alignment and appropriateness to remuneration in these entities.

Again, when studying these findings one is left with the distinct impression that without the necessary discipline of holding boards accountable for implementing guidelines there seems to be little constraint to the ever escalating executive pay scales. What is however also true is that in cases where there are strong boards and where proper remuneration practices have long been in place, SOEs do present a better overall picture of wage alignment and equality. An example that comes to mind is that of Transnet.

4.3. Views expressed by SOE boards, executives and middle management.

During a round-table exercise conducted with board, executive and middle management representatives during November 2011 the question of remuneration was pertinently raised.

The responses from the board representatives included strong calls for independent review and guiding principles to assist boards with making the right decisions. They also felt that

SOEs should not be painted with a single brush and that proper sizing and benchmarking is of critical importance. The mandates of SOEs would also have to play key roles in determining remuneration benchmarks.

They emphasised that board should account for the remuneration they awarded to executives against the performance of those executives. On the wage gap issue they stated that this is a global and systemic issue, which is best addressed as such. It would be irresponsible to just focus on SOEs as the “fix” to the remuneration gap. This feedback indicates that boards would welcome the existence of an independent advisory body.

Executives

Executives felt that remuneration had become such a big issue due to (1) the perception of non-performance of the entities and (2) the fact that in many cases SOEs are seen to be monopolistic and not having the same challenges as businesses operating in highly competitve environments. They believed though that the converse was true, that is, executives in SOEs have a much more complex environment to deal with. This is due to the diversity of stakeholders and the challenge to balance commercial objectives with developmental objectives. They felt though that the private and SOE sector were both looking for skills in the same market and this had an impact on remuneration levels.

These executives stated that an entitlement culture was still highly prevalent in SOEs and that nonperforming executives were still “paid to go” rather than answer for their nonperformance. The reason for existence of some SOEs also had to be looked at much deeper as it appeared that amalgamated entities did much better and warranted higher salaries for executives. They felt that longer term performance cycles needed to be used in setting remuneration. However, they were not comfortable with a higher performance-based component of executive pay.

On remuneration guidelines they were clear that what DPE issued in 2007 was not appropriate for the market in which they were operating and having to procure skills. They felt that guidelines should be put aside and that boards should retain ultimate responsibility for setting remuneration.

With regard the wage gap it was clear that not many SOEs at this level give much attention to it. There was however a strong view expressed that the wage gap is more of a symptom of a skills gap. The right way to address this was through more vigorous skills development.

This would, however, make SOEs vulnerable again to losing the skills to the private sector.

Middle managers

Middle managers stated that SOEs:

carried too much staff and

there were high degrees of laziness witnessed

According to middle managers remuneration was not linked to performance and that in general SOEs were ineffective in measuring performance. They held a different position to executives on guaranteed versus variable performance based pay. They believed a larger portion of remuneration needed to be put at risk (variable) by linking it to performance.

Middle managers also stated that the setting of remuneration levels needed to take into account:

skills

skills scarcity

the size of the organisation

the market influences on the organisation

An analysis of the feedback above brought the following to light:

there are vast differences as to how various levels in the organisation view the issue of remuneration

some boards in SOEs seem not to be able to provide proper leadership and guidance in remuneration practices and metrics. They are not held accountable for poor decision making thus perpetuating an already flawed situation

there is support for an independent body that could provide proper benchmarks and guidelines for remuneration;

comparison of remuneration of SOEs to the general market was acceptable given the challenges facing executives of SOEs

the link between performance and remuneration was not properly managed and accounted for in SOEs

there was no process in place for managing consequences, especially poor performance

the consolidation of SOEs was one way of improving performance and motivating higher levels of remuneration.

4.4. International Perspectives on SOE Remuneration

During November 2011 a subgroup of the PRC was sponsored to undertake a benchmarking tour to Europe where countries like Poland, Norway, Germany, Netherlands and France were visited. Although the group was asked to gather more details on remuneration, information sharing was limited. It appeared the issue of remuneration is as much a problematic, if not confusing, area by these European countries as it is in South Africa.

Following are some of the key findings of this subgroup:

In the Netherlands a previous government introduced a strategy to reduce SOE salaries to come in under that of the senior politician, but it seems they had problems implementing this. The remuneration of board members though was made partly dependent on the financial and public performance of the company.

In the Netherlands too, the shareholders had the right to define the remuneration policy headlines of the SOE. The Ministry of Finance also produced a policy in remuneration, which identified three categories of SOEs. Upper pay ranges for each category were capped. These categories are: (1) SOEs with a role in the economy and close to government (e.g. services); (2) SOEs with a clear public role and interest, also competing with private sector companies and (3) SOEs that were clearly private companies e.g. airports company.

In Germany salaries of SOEs are positioned to be competitive but it is aimed to keep them below the market average. How they position for competitiveness was not explained.

In Norway the remuneration of SOEs is a significant policy issue, particularly since it emerged that SOE executive pay was rising faster than their contemporaries elsewhere in the industry. Government, through the Ownership

Department, developed guidelines on remuneration that aimed at (1) inducing moderation in executive pay; (2) reduce severance packages; (3) ensure that variable pay did not exceed 50% of overall remuneration. SOEs are also required to develop a remuneration policy and submit it to the shareholder(s). In general it was aimed to make SOE remuneration much more transparent.

In Poland a draft bill on SOEs was not voted through parliament but was expected to resurface after the country’s 2011 general elections. This bill would have established Treasury as the point department for supervision and governance of SOEs. It furthermore proposed the abolishment of capped pay for

CEOs. With this capped pay policy, Treasury had to be notified when pay exceeded predetermined levels, even where the state had a less than 50% shareholding. The capping of CEO pay however meant that in some companies about 150 people earned more than the CEO.

In France the government’s ownership in companies is managed through the

Agencies des participations de l”Etat (APE). According to APE, remuneration was becoming more sensitive and the balancing of market forces with public sensitivities was an increasing challenge. The remuneration of executive staff was left in the ambit of board responsibilities but APE had representation on the board. From here they were seen to dominate in all probability dominated the debates as remuneration levels had to be approved by the Minister. An interesting approach to fixed and variable pay was introduced in stabilising the fixed component for two years (possibly placing more emphasis on two year performance cycles and the variable pay associated with that)

From these international perspectives it can be deduced that remuneration is a sensitive and troubling issue in the countries visited. The PRC was not able to undertake visits to Asia and determine some of the trends there. The OECD however reported that in most of the countries they co-operate with, the wage gap in SOEs was ever widening.

In an editorial article of the Business Day of 31 January 2012 the following excerpt appeared and which allowed for some understanding of how China approached SOE remuneration.

“The problem is that Chinese capitalism is so idiosyncratic and bound up with its history as a previously communist state that parallels with SA are hard to draw. The number and size of state-owned industries in SA is very small by comparison. The political and economic situation is vastly different. Just one example is that Wang

Jianzhou, the chairman and CEO of China Mobile, a company with 145000 employees and a turnover of about $70bn, technically earned $182000 in 2009. This is about a quarter of what Transnet CEO Brian Molefe earned last year for running a company with revenues about onetwentieth of China Mobile’s. The Chinese government’s power in the organisation and within society allows it to restrict the pay of everybody, from the CEO to ordinary workers. It’s no wonder they are such fearsome competitors internationally…..”

What are very clear from the international perspectives is that most governments are very aware of the public and political sensitivity of SOE executive remuneration. There are efforts and strategies introduced to bring some moderation into the process of rising salaries. It furthermore is clear that government or shareholder control in remuneration is quite strong and that there is a tendency to have the remuneration issues centralised under a

government department or agency.

In a report on interactions between private and public sector wages published by the

European Central Bank (ECB, 2008), insight into public sector versus private sector wages was obtained. In this report it was stated that in Greece, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Portugal – all economically troubled countries - real public sector wages have been significantly outstripping private sector wages over at least the last 20 years. Norway and Sweden – at the top of the pile in economic equality - present an opposite scenario. Private sector wages are constantly higher than public sector wages. A logical conclusion from this would be that there is a strong correlation between a too high public sector wage bill (in which we shall include SOEs) and a future of economic woes and potential bailout requirements. This issue will be addressed in section 5 in the report when South Africa’s public sector remuneration is compared with that of the private sector.

5. SOE REMUNERATION AND PRIVATE SECTOR BENCHMARKS

There are, as has been reported, different views from different stakeholders on how SOEs should be benchmarking themselves in terms of remuneration. As DPE explained, the guidelines issued from them have by and large been ignored by SOEs who insist that they need to be benchmarked against the private sector. As is shown in Graph 1 below, private sector benchmarking has actually led SOEs to pay higher salaries and wages at just about every level of employment (at median range).

Graph 1 – SOE remuneration benchmarked against private sector (21

st

Century, 2012)

Note: Patterson job grade scales were used throughout this report as indicated at X – axis above, where A1 represents most junior (unskilled) role and FU represents the highest end strategic management role.

The pay ranges that exist in SOEs and private sector companies is indicative again of how

SOEs are outliers when compared to similar roles in the private sector. In Table 4 below, the actual metrics on the position of SOE pay points to the private sector market are indicated.

At these pay levels one would expect a deliberate if not aggressive approach to performance management and achievement of set targets. Whether this is the case with SOEs is doubtful if one takes the feedback that has been coming forth from engagement with SOEs themselves as well as the customer base of SOEs.

In Table 5 the comparative ratio of the sample SOEs to the SOE median and the private sector market median is indicated per SOE. There is a range of deviation that is regarded as within the norm. However, according to 21 st Century, when a metric falls below 75 and above

125 a serious issue is indicated and some corrective steps need to be taken.

It would be appropriate to not only look at the outliers as indicated by the 25% gaps above, but consider every SOE for its particular role and contribution (plus job complexity) and to determine whether the remuneration levels are warranted. SOE salaries are a huge burden on the state and a more appropriate model could put extensive capital back in the fiscus for investment infrastructure and other developmental needs of the country. This is a point argued by Mike Schussler as part of the 21 st Century report section on wage differentials, which will be addressed in section 7.

Graph 2

– Upper and lower ranges of pay (below management): SOEs to

Private Sector (21

st

Century, 2012)

Graph 3 – Upper and lower ranges of pay (Upper management): SOEs to

Private Sector (21

st

Century, 2012)

Table 2 – SOE Comparative pay ratio to private sector – per job level* (21

st

Century, 2012)

Paterson

A1

A2

A3

B1

B2

B3

BU

C1

C2

C3

CU

D1

D2

D3

DU

EL

EU

FL

FU

Level

Unskilled /

Basic Skills

Operational

Skills

Advanced

Operational

Leader /

Specialist 368 623

426 038

Management /

Professional

565 284

635 862

Strategic

Execution

Strategic

Intent

SOE Median

Private Sector Comparative Ratio of SOE

38 238

Median

33 144 versus private

115

81 848

78 603

94 520

113 704

146 177

53 075

69 055

69 408

83 040

111 397

154

114

136

137

131

159 768

244 889

222 449

277 701

845 665

1 040 583

1 486 246

1 981 795

3 104 933

125 647

161 568

201 990

252 036

760 980

984 464

1 331 646

1 841 044

337 788

390 020

518 400

616 152

3 041 555

* 100 represent private sector benchmark in % terms

127

152

110

110

109

109

109

103

111

106

112

108

102

Table 3

– Comparative pay ratio of some of the sample SOEs to private sector and SOE medians* (21

st

Century, 2012)

Company Name

Compared to Private

Median

Compared to SOE

Median

AIR TRAFFIC NAVIGATION SERVICES (ATNS)

AIRPORTS COMPANY OF SOUTH AFRICA (ACSA)

132

108

120

95

AMATOLA WATER

ARMSCOR PTY LTD

109

106

96

98

AUDITOR GENERAL OF SOUTH AFRICA (AGSA)

BANKSETA

BROADBAND INFRACO

BUSHBUCKRIDGE WATER BOARD

CENTRAL ENERGY FUND

110

97

124

110

138

CITY POWER

CROSS-BORDER ROAD TRANSPORT AGENCY

138

COUNCIL FOR SCIENTIFIC & INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH-

CSIR 108

88

DENEL DYNAMICS 107

99

89

114

93

126

121

99

79

97

Company Name

Compared to Private

Median

Compared to SOE

Median

DEVELOPMENT BANK OF SOUTH AFRICA (DBSA)

EASTERN CAPE RURAL FINANCE CORPORATION

ESKOM

106

119

131

FINANCIAL SERVICES BOARD (FSB)

FOODBEV SETA

FREE STATE TOURISM AUTHORITY

115

114

104

GAUTENG FUND PROJECT OFFICE

GAUTENG GAMBLING BOARD

129

121

GAUTENG PARTNERSHIP FUND 129

INDEPENDENT COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY OF

SA (ICASA) 136

INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION (IDC)

114

ITHALA DEVELOPMENT FINANCE CORPORATION

LIMITED 81

JOHANNESBURG DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (JDA) 113

JOHANNESBURG SOCIAL HOUSING COMPANY

(JOSHCO) 77

LIMPOPO GAMBLING BOARD

MEDICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL (MRC)

113

82

97

93

117

105

104

92

118

112

118

122

106

71

103

69

104

76

MPUMALANGA TOURISM AND PARKS AGENCY

NATIONAL ARTS COUNCIL OF SOUTH AFRICA

122

NATIONAL GAMBLING BOARD

123

NATIONAL EMPOWERMENT FUND (NEF)

101

NATIONAL ENERGY REGULATOR OF SOUTH AFRICA

(NERSA) 118

82

NATIONAL RESEARCH FOUNDATION

102

NATIONAL URBAN RECONSTRUCTION AND HOUSING

AGENCY 114

NORTH WEST GAMBLING BOARD 116

NORTH WEST PARKS AND TOURISM BOARD 103

NUCLEAR ENERGY CORPORATION OF SOUTH

AFRICA (NECSA) 124

106

114

94

109

75

93

105

105

90

111

Company Name

PETRO SA

PETROLEUM AGENCY

PRASA

RAILWAY SAFETY REGULATOR

RAND WATER

ROAD TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT CORPORATION

SA CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY

SA EXPRESS

SA POST OFFICE

SERVICES SETA

123

115

115

121

SMALL ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (SEDA)

106

SOUTH AFRICAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION

(SABC) 119

SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL BLOOD SERVICE

(SANBS) 119

102

100

115

Compared to Private

Median

Compared to SOE

Median

121

125

115

111

116

96

112

102

100

110

93

86

102

97

109

104

SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL ROADS AGENCY LIMITED

122

SOUTH AFRICAN RESERVE BANK (SARB)

TELKOM SA LIMITED

124

109

TRANS-CALEDON TUNNEL AUTHORITY (TCTA)

TRANSNET

121

114

UMALUSI 112

* 100 represents private sector benchmark in % terms

112

113

100

112

99

101

6. SOE TAXONOMY MODEL FOR REMUNERATION

Part of the terms of reference for the Remuneration study was to develop a classification model or taxonomy of SOEs that would serve as a guide to the determination of remuneration levels and ranges for the individual entities. 21st Century was asked to develop such a taxonomy using the data they had gathered from the sample SOEs. They used the following elements as key determinants in this taxonomy that eventually came to 10 clusters of SOEs. (p 59)

Budget / Revenue of the SOE – A clear set of rules as to the use of either Budget or

Revenue as a dimension to be used. There are clearly significant differences in size between SOEs that are Budget or Revenue focused and a matrix to determine the relativity of each dimension has been constructed. The budget of some SOEs would be an appropriate measure. If one considered the revenue of SARS, they would be the biggest corporation in the country. In other cases the revenue generated from operations would be more important than the budget. Denel would be an example of such a SOE.

Operating costs

– Indicative of the relative financial space in which the SOE operates.

SAA may have an operating cost that is significantly higher than the operating cost of a similar organisation due to the nature of the operation. A matrix to recognise this dimension has been developed that is organisation-specific but applicable across the

SOE landscape.

Number of employees – This dimension would not just be about absolute numbers but also about the type of employees employed by the SOE. An organisation employing 200 professors may well remunerate the CEO at a higher level than the remuneration for a

CEO employing 2000 manual labourers.

Structure of the organisation

– Does the organisation have relative autonomy in the direction and strategic objectives that are set or are these dimensions mandated? Within the private sector a subsidiary of a holding company has a significantly reduced autonomy than the holding company itself.

Strategic intent of the organisation - This dimension would require participative agreement. Conceptually, when all of the above factors have been taken into account, two SOE’s could turn out to be the exact same ranking, but it would be obvious to anyone in a position of National Authority that one SOE is more strategically important than the other.

Number of operations / branches

– Another element that determines complexity of the role performed. At a superficial level the Reserve Bank operates from relatively fewer locations than SASSA, however the sheer number of SASSA offices undoubtedly adds to the complexity of management.

Number of core businesses

– Is the organisation involved in one specific area of authority (e.g. ICASA or CAA), or is the organisation involved in multiple and sometimes disparate types of operation (e.g. Transnet). The complexity of running an organisation can be reliably anchored on the number of core businesses managed.

Nature of the organisation – A Regulatory Body may be less or more complicated than another Regulatory Body. One could consider the scheduling status as defined by the treasury as input to this factor. For example, a body concerned with developing regulations that are specific to the South African context may well be considered to be operating in a more complex space than a body that simply adopts international standards and ensures that these are complied with (i.e. ISO 9000). Equally, an SOE that designs, manufactures, markets and sells products (e.g. Denel) may be considered more complicated than an organisation that simply ensures compliance with a predefined set of regulations. The nature of the organisation is a sound measure to determine the level of CEO or executive employed. Diversity of appropriate experience and ability would clearly be a determinant of remuneration.

Number of countries in which the SOE operates – Although a large number of the

SOEs examined have their roles confined to South Africa, there are a proportion that operate across borders. These operate in both Southern African and in a broader international context. In the same way that a dual listed executive is remunerated at a higher level than a single listed executive, the same may be said for executives in the

SOE environment. Understanding multiple legislatures, tax regimes, company laws etc. add complexity to the role. At another level, executives exposed to international markets operate within an international remuneration space.

Qualifications and experience required for performing the role – Certain roles have legislative qualification requirements and these should be factored. However, certain roles would have a combination of qualifications and experience. An example of this would be the difference in pay between the Auditor General and the Attorney General.

The 10 clusters were derived through multiple regression models to determine the weighting of the dimensions above. The sample of SOEs were then assessed according to the taxonomy and were positioned in the different categories or clusters as follows:

Table 4

– Application of Taxonomy to SOE sample (21

st

Century, 2012)

Organisation Cluster

NATIONAL GAMBLING BOARD; INVEST NORTH WEST; JOHANNESBURG SOCIAL HOUSING COMPANY

(JOSHCO); NATIONAL FILM AND VIDEO FOUNDATION; OMBUDSMAN FOR FINANCIAL SERVICES; MEDIA

DEVELOPMENT AND DIVERSITY AGENCY (MDDA); SA LIBRARY FOR THE BLIND; NATIONAL HERITAGE

COUNCIL; AFRICA INSTITUTE OF SOUTH AFRICA; CROSS-BORDER ROAD TRANSPORT AGENCY; LIMPOPO

GAMBLING BOARD; NATIONAL ARTS COUNCIL OF SOUTH AFRICA; FREE STATE TOURISM AUTHORITY;

GOVERNMENT EMPLOYEES PENSION FUND (GEPF); RURAL HOUSING LOAN FUND; THE MARKET THEATRE

FOUNDATION

1

EDUCATION LABOUR RELATIONS COUNCIL; FOODBEV SETA; GAUTENG GAMBLING BOARD; NATIONAL URBAN

RECONSTRUCTION AND HOUSING AGENCY; NORTH WEST GAMBLING BOARD; THE INDEPENDENT

REGULATORY BOARD FOR AUDITORS; THE JOBURG THEATRE; JOHANNESBURG DEVELOPMENT AGENCY

(JDA); RAILWAY SAFETY REGULATOR; SOUTH AFRICAN NURSING COUNCIL (SANC); UMALUSI; FASSET;

GAUTENG ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (GEDA); GAUTENG PARTNERSHIP FUND; NATIONAL

LOTTERIES BOARD; TECHNOLOGY INNOVATION AGENCY (TIA)

2

PORTS REGULATOR OF SA; HEALTH AND WELFARE SETA; MPUMALANGA TOURISM AND PARKS AGENCY;

NATIONAL METROLOGY INSTITUTE OF SOUTH AFRICA; ROBBEN ISLAND; LIMPOPO BUSINESS SUPPORT

AGENCY (LIBSA); BANKSETA; BUSHBUCKRIDGE WATER BOARD; ITHALA DEVELOPMENT FINANCE

CORPORATION LIMITED

3

NATIONAL ENERGY REGULATOR OF SOUTH AFRICA (NERSA); SOUTH AFRICAN WEATHER SERVICE (SAWS);

INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION CENTRE DURBAN (ICC); SA CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY; SASRIA LIMITED;

FINANCIAL SERVICES BOARD (FSB); SOUTH AFRICAN MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY (SAMSA)

4

AMATOLA WATER ; BROADBAND INFRACO; MEDICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL (MRC); TRANS-CALEDON TUNNEL

AUTHORITY (TCTA); HUMAN SCIENCES RESEARCH COUNCIL (HSRC); NATIONAL EMPOWERMENT FUND (NEF);

WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION; INDEPENDENT COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY OF SA (ICASA); MERSETA;

EASTERN CAPE RURAL FINANCE CORPORATION; PIKITUP; SERVICES SETA; SMALL ENTERPRISE

DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (SEDA); ARMSCOR PTY LTD; COUNCIL FOR SCIENTIFIC & INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH-

CSIR; NUCLEAR ENERGY CORPORATION OF SOUTH AFRICA (NECSA)

5

DEVELOPMENT BANK OF SOUTH AFRICA (DBSA); AIR TRAFFIC NAVIGATION SERVICES (ATNS); AIRPORTS

COMPANY OF SOUTH AFRICA (ACSA); DENEL DYNAMICS; CITY POWER; EZEMVELO KZN WILDLIFE; SA

EXPRESS; SAFCOL; UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG; AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL

(AIDC); LAND BANK

6

Organisation Cluster

AUDITOR GENERAL OF SOUTH AFRICA (AGSA); NATIONAL RESEARCH FOUNDATION; RAND WATER; SOUTH

AFRICAN NATIONAL ROADS AGENCY LIMITED; SOUTH AFRICAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION (SABC);

CENTRAL ENERGY FUND; SA POST OFFICE

7

INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION (IDC); SOUTH AFRICAN RESERVE BANK (SARB) 8

PETRO SA; PRASA 9

TRANSNET; ESKOM; TELKOM SA LIMITED 10

This taxonomy only covers the SOEs that formed part of the sample provided by the PRC in conjunction with its Research and Development Unit (RDU) and the HSRC. It does, however, provide a clear method and formula to determine the positioning point of SOEs relative to each other. It could serve as a valuable tool to categorise SOEs in future for the purposes of remuneration or other analyses. A web-based tool that enables all SOEs, shareholder executives and other stakeholders to determine the positioning point of a specific SOE relative to another further supports the taxonomy. This allows for clear indicators and parameters on pay points per job grade that applies to that specific SOE. To put perspective to this taxonomy the following table shows the relative pay ranges for the 10 different categories from Patterson levels A to D.

Table 5

– Pay progression between company sizes in SOE market (A-D levels)

Although the dimensions that were used in this taxonomy bring about a high degree of granularity in distinguishing one SOE from another, there may be other aspects, which should also be included to assist with an even better discrimination – although the latter would need to be statistically tested. One such dimension is the Strategic Risk Factor (e.g. if

Eskom collapses) but this may well be a subset of the Strategic Intent dimension.

One of the critical areas to address further is the dimension of strategic intent. 21 st Century suggests that it cannot be dependent on them to determine the strategic intent dimension of the SOE in question. The delineation of it would have an impact on the categorization

(although they feel it may only change a category one up or down). The issue of strategic intent - and where it originates from - was extensively debated and the PRC has taken the view that the first place to look for differentiating definitions would be in the current proposed categorization model. A useful model for categorizing State Owned Entities was done by

Genesis Analytics (in BUSA, 2011) as contained in Figure 1 below. This model also appears in presentations by National Treasury.

It would be important to determine which SOEs fall under the different categories mentioned in the model and to what extent the 10 Category Taxonomy supports the current classification model. It may be that in Stewardship or Service delivery entities, as example, the range of categorized SOEs may be as wide as eight categories. This would indicate that strategic intent might have a lower influence than the combination of other key dimensions.

This may be a correct interpretation as the complexity of an organization is often determined more by size and diversity or number of divisions/business units than by the subject of its mandate. Additional research work is being undertaken on this matching process.

Figure 1

– A categorisation of State Owned Enterprises (Genesis Analytics)

(BUSA submission, 2011)

7. WAGE CONTRIBUTIONS TO INEQUALITY

Part of the terms of reference related to remuneration focused on the ever-widening wage gap problem and strategies on how to reverse the trend. In a presentation delivered to the

SMOE team by 21 st Century in February 2012 various elements of the wage gap or wage differential were addressed that provided a clear picture of these impacts.

The wage differential is normally synonym with the level of inequality that exists within a chosen or defined population. This level of inequality is presented in the form of a coefficient where zero means there is no inequality (everyone earns the same) and where 1.0 means there is maximum inequality (one person earns all the income). This coefficient – called the

Gini coefficient – is also expressed in percentile format and the closer a population comes to

100 the higher the degree of inequality. The Gini coefficient may not always be the most reliable measure to assess the quality of life of the citizens of different countries. In the graphic and table below there are clear indications that in some “high inequality societies” - like South Africa - people may have a much better quality of life than those in countries with lower inequality ratings such as Zimbabwe, Nigeria and India. Quality of life includes aspects such as life expectancy, the human development index, improved water sources and overall access and crude death rate (death per 1000 population).

Figure 2: Gini coefficient in world – from CIA’s The World Factbook 2009 (CIA website)

Table 6: Gini coefficient by country

– CIA The World Factbook (CIA, 2012)

1 Namibia

2 Seychelles

70.7

65.8

3

4

5

13

14

South Africa 65.0

Lesotho

Botswana

63.2

63.0

Brazil

Thailand

53.9

53.6

70

71

83

94

46

52

53

62

28

40

41

42

15

25

26

27

Hong Kong

Zimbabwe

Dominican Republic

Peru

53.3

50.1

48.4

48.0

Singapore 47.8

United States 45.0

Cameroon

Iran

44.6

44.5

Nigeria

Russia

China

Turkey

Malawi

Mauritius

India

United Kingdom

43.7

42.0

41.5

40.2

39.0

39.0

36.8 #

34.0

97

101

102

106

107

111

113

120

Switzerland

Greece

France

Spain

Italy

Korea, South

Netherlands

Ireland

33.7

33.0

32.7

32.0

32.0

31.0

30.9

29.3

129

135

136

137

Germany

Luxembourg

Malta

Norway

27.0

26.0

26.0

25.0

140

*

Sweden 23.0

* Data collected over periods ranging from 1989 to 2010

# Red line indicates where SOEs in South Africa rate

According to 21 st Century the current Gini coefficient for State Owned Entities is 34.8

(denoted by red line). This is significantly lower than the rest of the country and would immediately give the observer a sense of comfort that SOEs are actively reducing the wage gap. The sustainability of this approach is questionable as the SOEs at the median level pay anywhere between a 102% and 140% of private sector salaries at all levels of employment.

This means that when executive level salaries leap forward, so too do salaries at lower level.

Eventually the salary burdens become too large for the entity or company to carry, who then need to revert to the state for financial relief.

Inequality remains an important indicator of the degree of social stability and health in different countries. In the 21 st Century presentation done to the SMOE work group, the correlation between inequality and social ills were found to be very high and almost linear, bar for a couple of outliers. In their first sample, Japan was the country with the lowest inequality with Singapore and the USA at the highest end (at least 2.5 times that of Japan).

The following correlations were pointed out quite clearly:

the higher the inequality, the lower the life expectancy

the higher the inequality, the higher the infant mortality (except in Singapore)

the higher the inequality, the higher the level of obesity

the higher inequality, the higher unemployment

the higher the inequality, the higher the percentage of teenage pregnancies and births

the higher the inequality, the higher the percentage of homicides

the higher the inequality, the higher the levels of imprisonment

the higher the inequality, the lower the number of average years of schooling

(Portugal a lower outlier and USA a higher outlier)

South Africa has an inequality rate of at least double that of Singapore. When South Africa is included in the data sets , and with the continuation of the linearity, all the issues above become exponentially worse.

According to a paper published by the OECD in 2008, income in South Africa has become increasingly concentrated in the top decile. Across the three years the richest 10% accounted for 54%, 57% and 58% of total income respectively. The share of income accruing to the richest 10 percent increased at the expense of all other income deciles. The cumulative share of income accruing to the first five deciles (lowest

50%) decreased from 8.32% in 1993 to 7.79% in 2008 (OECD, 2010).

It thus holds that the oftenmentioned theme of a “ticking time bomb” is exactly that. South