Complex_trauma_papers

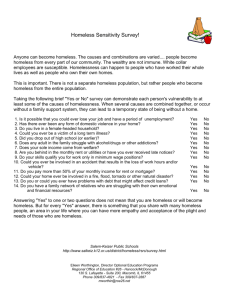

advertisement