Article: "The Riba-Interest Equation and Islam: Reexamination of the

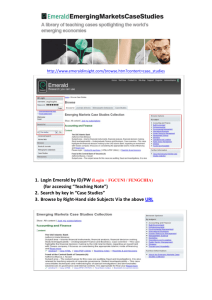

advertisement