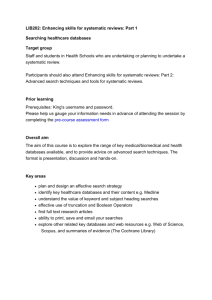

THE NATIONAL KNOWLEDGE SERVICE - e

advertisement