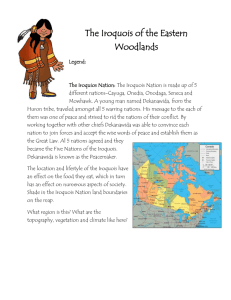

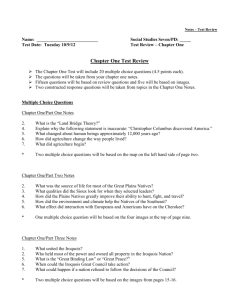

Cultural Group - Pacific University

advertisement