Downloadable MS Word Format

Corporate Exchange Issues

By Gregory J. Rocca and Michael K. Phillips

Copyright © 2005 Pacific Realty Exchange, Inc. All rights reserved.

The different tax treatment of corporations as compared to individuals and other entities raises special issues for corporations that engage in like-kind exchanges. Corporations are different because they do not enjoy a capital gains preference, such as the 15% rate applicable to the longterm capital gains of individuals. Corporations also face different AMT rules. The tax benefit of an installment sale is reduced or eliminated by the interest charge on installment sales exceeding

$5 million. These factors, as well as corporate tax rates, may increase the relative desirability of a tax-deferred exchange for a corporate taxpayer. Corporations frequently engage in Section

1031 exchanges as a means of plant and equipment replacements (including aircraft and leased vehicles), addressing asset-based financial concerns, making divestitures preceding or following mergers and acquisitions, and increasing real estate holdings (primarily REITs).

Corporations are also subject to special rules for consolidated groups if they are affiliated.

Corporations may engage in various types of corporate reorganizations before, during and after completion of an exchange. Corporations typically own business assets other than real estate, including depreciable tangible personal property (such as planes, trains and automobiles) and intangible personal property (such as patents, franchises, and licenses). Much more restrictive like-kind rules apply to personal property, as compared to the very broad like-kind rule for real estate. Multinational corporations are the most likely taxpayers to be affected by Section 1031(h) which restricts exchanges of U.S. for foreign property and foreign for U.S. property. Finally, corporations may be sensitive to the financial reporting of exchange transactions under GAAP.

However, Section 1031 exchanges are on the “angel’s list” of items that are excluded from booktax differentials that may cause tax shelter reporting and registration.

In general, the same corporation that starts an exchange by relinquishing property must complete the exchange by receiving the replacement property. There is no blanket exception for consolidated group members, such that an exchange of relinquished property by a subsidiary may be completed by the parent corporation receiving the replacement property. The line of authorities applicable to “holding” property for a qualified use under Section 1031 applies to corporations, including authorities relating to pre-exchange and post-exchange contributions and distributions. However, a receipt or drop-down of property to a single-member LLC that is treated as a disregarded entity for tax purposes is allowed. See PLRs 199911033, 9850001,

9807013 and 9751012. Further, the IRS has ruled that corporate successors in Section 381 transactions, such as Section 332 liquidations and certain corporate reorganizations under

Section 368, can complete a like-kind exchange. See PLRs 9850001, 9751012, 9252001 and

9152010. The “holding” and “qualified use” requirements may also affect various transactions in which a taxpayer desires to transfer real property and ultimately end up with an interest in a real estate investment trust (REIT).

Exchanges Between Affiliates.

Consolidated returns can be filed by affiliated corporations which are part of a consolidated group under Section 1501. The concept is to treat the consolidated group as single economic

unit. These rules are generally beneficial to affiliated groups. The consolidated return regulations provide that Section 1031 does not apply to any intercompany transactions occurring in consolidated return years beginning on or after July 12, 1995. Reg. Section 1.1502-80(f). Thus, like-kind exchanges between the corporate members of an affiliated group that files a consolidated return are not governed by Section 1031. Rather, exchanges between affiliated corporations are subject to the intercompany transaction rules. Gain or loss on such exchanges is deferred under the deferred intercompany transaction (“DIT”) rules of Reg. Section 1.1502-13.

Gain from a DIT is triggered to the exchanger when either the exchanger’s property or the affiliated transferee leaves the consolidated group. These rules are similar to the related party exchange rules of Section 1031(f) except that they are of unlimited duration (not just applicable for two years as under Section 1031(f)) and gain is only triggered to the exchanger in such cases

(not both parties as under Section 1031(f)).

Section 1031 does apply to a subsequent exchange by a group member with a non-member following a DIT, including (but not limited to) an exchange between affiliates. The transfer of property outside the consolidated group in a Section 1031 exchange with a non-member does not trigger the gain from the prior DIT (except to the extent that the group member receives boot in the exchange). See Reg. Sections 1.1502-13(b)(3)(ii) and 13(c)(7), Example 1(h). Instead, the gain from the DIT is not triggered until the group member disposes of the replacement property that it received in the Section 1031 exchange with the non-member outside of the consolidated group. As noted above, the “holding” and “qualified use” requirements still must be satisfied with respect to the Section 1031 exchange if a DIT is followed by a like-kind exchange with a non-member or if a like-kind exchange with a non-member is followed by a DIT.

Example:

• Affiliated corporations A and B each own like-kind property

• A owns X with 100 FMV, 10 Adjusted Basis, 90 Gain

• B owns Y with 100 FMV, 80 Adjusted Basis, 20 Gain

• X is to be sold, but Group wants B to own replacement property Z

• A and B exchange X for Y, B then trades X for Z

Section 1031 does not apply to the exchange of X for Y between consolidated group members A and B. The exchange is a DIT. The DIT gain of A (the original owner of X) would be triggered on a sale of X by B outside the group. But if B makes a subsequent Section 1031 exchange of X for Z with a non-member the prior DIT gain of A should not be triggered (except to the extent that B receives any boot in the exchange) until B disposes of Z outside of the group. The tax treatment of post-exchange dispositions under the DIT rules may be more certain than for similar dispositions under Section 1031(f). Further, the DIT gain deferred by B on the exchange is only triggered to B if A disposes of Y or leaves the group.

Controlled partnerships may be used to avoid the prohibition on Section 1031 exchanges among group members. A partnership owned 100% by group members is not itself a member of the consolidated group (unlike a corporation, a partnership cannot be part of an affiliated group). A

Section 1031 exchange with a controlled partnership is subject to the related party exchange rules of Section 1031 and is not a DIT. Thus, gain is triggered on the exchange only if either property is disposed of the two-year period following the exchange under Section 1031(f) (not a

holding or tracking period of unlimited duration under the DIT rules). An asset sale to a controlled partnership was respected by the IRS in PLR 9645015.

Proposed regulations under Section 1.1502-13 contained an example of the use of a controlled partnership to escape treatment as an affiliated group. The example held that the use of such a partnership to avoid the DIT rules was an “abuse”. The example was deleted in the final regulations. See the DIT anti-abuse rules of Reg. Section 1.1502-13(h)(1). But the preamble to the final regulations warned of the potential application of the partnership anti-abuse rules of

Reg. Section 1.701-2. The IRS could also use judicial doctrines to attack related party transactions that it viewed as abusive. In FSA 199929009 and FSA 1999-1162, the IRS noted the potential application of the step transaction and substance over form doctrines to basis-shifting exchanges between a parent and subsidiary in anticipation of the sale of the unwanted low-basis property shortly after the exchange. The transactions predated Reg. Section 1.1502-13, and thus the IRS analyzed the transactions under general tax principles.

Similarly, in FSA 200244010, the IRS concluded that the doctrines of business purpose, step transaction and substance over form could be used to disregard a Section 1031 exchange designed to shift the basis of exchanged aircraft and accelerate depreciation. The taxpayer was a parent corporation that purchased and leased back a new airplane to a foreign airline. Due to the lease to a foreign person, the taxpayer would have been forced to depreciate the cost basis of the new plane using the alternative depreciation system (ADS) in Section 168(g) (straight-line depreciation over a 12-year class life). After the purchase and leaseback, however, the taxpayer exchanged the new plane for eight, substantially depreciated, domestic aircraft owned by a subsidiary. The taxpayer’s cost basis of the new plane was then shifted under Section 1031(d) to the eight old aircraft, and the taxpayer claimed accelerated depreciation on the domestic aircraft over a 7-year recovery period under MACRS. The transactions occurred before 1995 and predated Treas. Reg. Section 1.168(h)-1 (which prevents such basis freshening using a like-kind exchange). The IRS concluded that judicial doctrines allow the IRS to disregard the Section 1031 exchange, thereby achieving the same result as provided in Reg. Section 1.168(h)-1. The FSA cited the recent case of True v. United States, 190 F.3d 1165 (10th Cir. 1999), which applied the business purpose and step transaction doctrines to disregard a Section 1031 exchange and prevent a taxpayer from effectively depleting the cost basis of recently-purchased ranch land that could not otherwise be depreciated or depleted.

Effect of Consolidated Groups and Reorganization Provisions.

The effect of the DIT rules applicable to members of consolidated groups who engage in Section

1031 exchanges is illustrated by Reg. Section 1.1502-13(c)(7), Example 1(h). This is an example of an intercompany sale between group members followed by a Section 1031 exchange with a non-member. P is the common parent of the P consolidated group, P owns all the only class stock of subsidiaries S and B, and X is a person unrelated to any member of the P group. S holds land for investment with a basis of $70. In Year 1, S sells the land to B for $100. S does not recognize the $30 gain under the DIT rules. In year 3, B exchanges the land for property R owned by X in a Section 1031 exchange. There is no difference in Year 3 between B’s $0 corresponding item taken into account and the $0 recomputed corresponding item. Thus, none of

S’s intercompany gain is taken into account under the matching rule as a result of the Section

1031 exchange. Instead, B’s gain is preserved in property R received from X. Under the successor asset rule, S’s intercompany gain is taken into account by reference to property R, B’s replacement property. If B takes gain into account as a result of boot received in the Section

1031 exchange with X, S’s intercompany gain is taken into account under the matching rule to the extent the boot causes a difference between B’s gain taken into account and the recomputed gain.

The effect of a corporate reorganization immediately after an exchange is examined in PLR

9850001. In PLR 9850001 the IRS ruled that the liquidation and merger of a company involved in a like-kind exchange will not disqualify the exchange under Section 1031. The company that started the exchange was owned by a U.S. holding company subsidiary of a foreign corporation.

The company transferred hotel property to a qualified intermediary in a like-kind exchange.

After transferring the property, but before receiving the replacement property, it formed a limited liability company (a single-member LLC treated as a disregarded entity) and directed the replacement property to be transferred to its newly formed LLC. After the LLC receives the property, the company will liquidate into its holding company parent, which will then merge with another U.S. operating subsidiary of the foreign corporation. The statutory merger will qualify as a tax-free reorganization under Section 368(a)(1)(A). That subsidiary will then be the sole owner of the LLC, but plans to transfer its interest in the LLC to another LLC that it already owns and that is treated as a disregarded entity. Due to the special provisions of Section 381, the

IRS ruled that the liquidation and merger of the company will not violate the Section 1031(a)(1) requirement that the company “hold” the replacement property for productive use in a trade or business or for investment. Additionally, the IRS ruled that the surviving subsidiary’s transfer of the LLC to another LLC will not adversely affect the like-kind exchange since the LLC is a disregarded entity for tax purposes.

The IRS noted that Section 368(a)(1)(A) provides that the term "reorganization" includes a statutory merger or consolidation. Section 1.381(a)-1(b)(3)(i) of the regulations provides, in part, that Section 381 does not apply to the carryover of an item or tax attribute not specified in

Section 381(c). Section 381(c) does not refer to like kind exchanges under Section 1031.

However, the legislative history of Section 381 explains that "[T]he section is not intended to affect the carryover treatment of an item or tax attribute not specified in the section or the carryover treatment of items or tax attributes in corporate transactions not described in subsection (a). No inference is to be drawn from the enactment of this section whether any item or tax attribute may be utilized by a successor or predecessor corporation under existing law." H.

R. Rep. No. 1337, 83rd Cong., 2d Sess. A135 (1954). See also section 1.381(a)-1(b)(3)(i) of the regulations (to the same effect). In other words, Congress did not intend the tax attributes listed in Section 381(c) to be the exclusive list of attributes available for carryover. The IRS stated that the legislative history further reveals that the purpose of Section 381 is to put into practice the policy that "economic realities rather than ... such artificialities as the legal form of the reorganization" ought to control in the question of whether a tax attribute from an acquired corporation is to be carried over to the acquiring one. Section 381 was enacted "to enable the successor corporation to step into the 'tax shoes' of its predecessor corporation without necessarily conforming to artificial legal requirements which [then existed at the time of its enactment] under court-made law." See S. Rep. No. 1622, 83rd Cong., 2d Sess. 52 (1954).

The IRS found that the stated rationales for Section 1031 (continuity of investment and administrative convenience) “are equally applicable when, as a result of a liquidation under section 332 or a reorganization under section 368(a)(1)(A), a successor corporation obtains ownership of like kind property previously received by a liquidated or an acquired corporation in a transaction to which section 1031 applies. Accordingly, we conclude that for purposes of section 1031(a)(1) there is a carryover of tax attributes following both a section 332 liquidation and a section 368(a)(1)(A) reorganization. Thus, the intervening liquidation and reorganization, under the facts of this case, will not affect whether the replacement property is held for productive use in a trade or business or for investment.” Accordingly, the IRS ruled that the liquidation of the company into the holding company, and the merger of the holding company into the subsidiary, will have no effect on the requirement under Section 1031 (a)(1) that the replacement property be “held” [by the taxpayer] for the productive use in a trade or business or for investment. See also PLR 9751012.

Thus, midstream or post-exchange corporate reorganizations are permitted. The surviving company is treated as succeeding to the disappearing company's “qualified use” and other tax attributes for purposes of Section 1031. The key is the availability of Section 381. Section 381 applies to Section 332 liquidations of a subsidiary into a parent company and reorganizations under subparagraphs (A)(statutory mergers), (C) (stock for assets), (D)(divisive reorganizations and spin-offs), (F) (mere change in identity, form, or place of organization), and (G) (transfers of assets in connection with a title 11 or similar bankruptcy case) of Section 368(a)(1). But Section

381 does not apply to stock-for-stock “B” reorganizations. Further, there is no Subchapter K analogue to Section 381 applicable to partnerships, or similar analogue applicable to individuals.

But see Section 708(b)(2)(A) (in a partnership merger, successor partnership is partnership with more than 50% common ownership with prior partnership) and PLR 9829025 (executor or successor trustee may complete deceased individual’s deferred exchange in certain circumstances).

TAM 9252001 applied the same analysis as PLR 9850001 to an exchange by a corporation

(Corp. M) that merged before the completion of a deferred exchange. After Corp. M transferred the relinquished property in a deferred exchange and before it received a certain replacement property, Corp. M was merged with another corporation into a third corporation (Corp. O) under

Section 368(a)(1)(A). Then the stock of the third surviving corporation (Corp. O) was distributed in a spin-off by the taxpayer to the taxpayer’s shareholders in a tax-free reorganization that qualified under Section 368(a)(1)(D) and Section 355(a)(1). The IRS ruled that the intervening merger and spin-off did not prevent the receipt of the replacement property by Corp. O in a deferred exchange from being treated as received in exchange for Corp. M’s earlier transfer of the relinquished property.

In PLR 9152010, the IRS applied the same analysis to a very interesting transaction involving a

REIT’s acquisition of an exchanging corporation’s assets in exchange for the REIT’s stock in a

“C” reorganization. The exchanging corporation wanted to convert its existing real estate holdings into properties that would be considered investment grade for a publicly traded REIT and then seek to be acquired by a REIT. The exchanging corporation found a buyer and transferred the relinquished property in a deferred exchange. The acquiring REIT wanted to participate in the identification and acquisition of the replacement property. Thus, the

exchanging corporation was acquired by the REIT after the acquired corporation’s transfer of the relinquished property but before the acquisition of the replacement property. The IRS ruled that, for purposes of Section 1031, the REIT will step into the shoes of the acquired corporation and be treated as the transferor of the relinquished property even though the relinquished property was transferred in a deferred exchange before the “C” reorganization. Again, the key to this holding is the application of Section 381 which allows the acquiring corporation (the REIT in the ruling) to succeed to and take into account tax items and attributes of the acquired corporation in a “C” reorganization.

In connection with certain corporate acquisitions, buyers have considered the effect of making a

Section 338(h)(10) election but the election does not work to create like-kind property that the buyer may exchange into under Section 1031. These transactions involve the purchase of S

(subsidiary) stock from P (parent) by buyer B. Under a Section 338(h)(10) election, the transaction is treated as the purchase of S assets by NewS and sale of S assets by OldS, as part of

P's affiliated group. The gain in the deemed sale of assets by OldS is triggered, and B receives a step-up in the basis of the assets through the deemed purchase of S assets by NewS. However, the transaction is still treated for purposes of Section 1031 as a purchase of stock which is excluded property under Section 1031(a)(2) and is not of like kind to any assets eligible for

Section 1031 treatment. As an alternative, buyers have considered structures using LLCs. These structures require planning and the seller’s cooperation. S’s assets are transferred to a singlemember LLC (SMLLC) prior to sale. Since the SMLLC is a disregarded entity for tax purposes,

B's purchase of the SMLLC membership interest is treated as an asset acquisition. Delaware

Series LLCs may be used to isolate S’s assets into classes or specific S assets may be dropped down into a SMLLC prior to the sale and in anticipation of a future Section 1031 exchange by B into those assets.

Replacement Property Options.

Corporations that exchange real estate benefit from the broad like-kind rule applicable to real estate. They may trade residential rental property for commercial property, business property for investment property, improved property for unimproved land, or a fee interest in property for an undivided interest or a leasehold interest with 30 years or more to run. Corporations have a broad array of replacement property options with respect to real estate exchanges. Some of the interesting issues include the creative use of leasehold interests and build-to-suit exchanges as discussed in Part III above, synthetic leases, and exchanges involving REITS.

Corporations may also acquire the lessee’s interest in a “synthetic lease” as replacement property in a Section 1031 exchange. Under a synthetic lease, the lessee is treated as the owner of the property for tax purposes. The lessee is allowed the depreciation and interest deductions for tax purposes. The lessee can acquire the property as replacement property in a Section 1031 exchange since the lessee is considered to be the beneficial owner of the property for tax purposes. However, the lessee under certain synthetic leases is treated as a lessee and not as the owner for financial reporting purposes. Thus, synthetic leases are used for financial reporting purposes to keep assets and related debt off the corporation’s balance as a means to improving certain financial ratios, such as the return on assets, debt/equity ratio, return on equity and earnings per share. FASB 13 and FASB 98 detail the fundamental requirements for treatment of

a synthetic lease as an operating lease for financial reporting purposes, including requirements that the lessee does not have the automatic right to acquire title, there is no bargain purchase option, the lease term is less than 75% of estimated economic life of the property, and the present value of minimum lease payments is less than 90% of the property’s value.

Section 1031 exchanges are very attractive to REITs because exchanges avoid the need to distribute proceeds and shrink their capital base. Thus, exchanges give REITs the opportunity to increase their holdings significantly. The use of reverse exchanges allows REITs to have integrated purchase and sale transactions and ensures that they acquire investment grade properties. Exchanges by REITs can be very complicated due to the large size of the transactions, multiple property exchange issues, prohibited transaction issues, and GAAP issues.

Exchanges by other taxpayers into REITs can be even more complicated. Shares of stock in a

REIT or a partnership interest in a typical UPREIT structure are excluded property under Section

1031(a)(2) and may not be received tax-free in exchange for relinquished property. If the exchanging taxpayer is a corporation, a “C” reorganization into the REIT may be possible. See

PLR 9152010 (discussed above). If the exchanging taxpayer is an individual or a partnership, however, complicated structures must be used. These structures involve pre-exchange contributions to a REIT operating partnership (OP) with OP subsequently making a Section 1031 exchange for investment grade property, a post-exchange contribution to OP with the taxpayer first completing a Section 1031 of its relinquished property for investment grade property, and merger of an exchanging partnership into OP (in the case of an exchanger that is a partnership).

These structures raise issues under Section 1031 with respect to the “holding” and “qualified use” requirements, as well as step transaction and substance over form issues (is the end result and substance of the transactions the taxable receipt of excluded property?). Taxpayers frequently desire to convert direct ownership to REIT ownership to eliminate management responsibility, create liquidity, receive stable returns and diversify investments. But the disadvantages of direct or indirect REIT ownership include the loss of control, the significant transaction costs and tax risks associated with a pre-exchange or post-exchange contribution to

OP, and the triggering and allocation of the pre-contribution gain to the taxpayer under Section

704(c) if OP disposes of the replacement property in a taxable transaction.

Corporations that exchange entire businesses and personal property have much more limited replacement property options. The transactions must be structured as dispositions and acquisitions of assets since stock cannot be exchanged under Section 1031. Further, the transaction is treated as a disposition of individual assets, although the individual assets may be grouped together into like-kind exchange groups for purposes of determining boot and making other tax computations under Section 1031. See Reg. Section 1.1031(j)-1 (the multiple property exchange regulations). The key limitation on exchanges of businesses and personal property is the very narrow and restrictive like-kind rules applicable to personal property. See Reg. Section

1.1031(a)-2. Under these regulations, there are two ways for a taxpayer to achieve like-kind treatment for Section 1031 exchanges of properties that constitute depreciable tangible personal property: (i) characterize the properties as like kind, which the regulations define as having the same nature or character; or (ii) characterize the properties as like-class. The like-class standard uses both General Asset Classes and Product Classes. With respect to Product Classes, new regulations under Section 1031 replace the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) system of

codes with the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) for purposes of determining what depreciable tangible personal property is of like class to other property. For transfers of property on or before the date of publication of final regulations, taxpayers may treat properties within the same SIC product class or the same NAICS product class as property of a like class and of like-kind. T.D. 9151 (8/12/04).

Little guidance existed for determining the like-kind status of depreciable tangible personal property until 1991 when the regulations were issued. Earlier cases allowed certain personal property exchanges without detailed analysis of the like-kind requirement as applied to personal property. The cases allowed exchanges of printing press for printing press, car for car, well equipment for well equipment, buses for buses, trucks for trucks, and construction and excavation equipment, dairy farm equipment, and oil and gas equipment for the same kind of equipment. In 1991 the regulations created the like-class standard for depreciable tangible personal property exchanges based on General Asset Classes and Product Classes. The like-class standard is a safe harbor under which the properties will be treated as like kind. The regulations provide that in determining whether personal properties are of like kind, no inference is to be drawn from the fact that the properties are not of a like class.

In its rulings on personal property exchanges, however, the IRS has taken the position that the lenient standard applied to real property exchanges is not appropriate for personal property exchanges, citing California Federal Life Insurance Co.v. Commissioner, 680 F.2d 85 (9th Cir.

1982), aff'g 76 T.C. 107 (1981). This case held that Swiss francs and U.S. double-eagle gold coins were not of like kind. See also FSA 199941005 (taxpayer could not demonstrate that certain machinery and equipment were of like kind even if they were not in the same Product

Class and thus not of a like class). In many rulings on vehicle exchanges, the IRS has ruled that automobiles and SUVs are of like kind to each other, but neither is of like kind to trucks. The restrictive like-kind rules for personal property place major constraints on the replacement property options for corporations exchanging businesses and personal property. Unless the exchanged properties are of a like class, taxpayers may be hard pressed to argue that the properties have the same “nature or character” (as distinguished from differences in grade or quality) under the general like-kind rule.

In FSA 199941005 (June 10, 1999), the taxpayer exchanged business assets and treated the exchange as an exchange of multiple properties in accordance with Reg. Section 1.1031(j)-1. The bulk of the assets were categorized into exchange groups using General Asset classes. But the remaining assets consisting of certain machinery and equipment were combined into one group.

The revenue agent argued that the assets should be broken down into three different exchange groups based on three separate SIC product codes. This would result in the recognition of additional gain by the taxpayer. The taxpayer argued that the assets were of a “like kind,” even if they were not in the same product class and of a like class.

The Service found that there were sufficient distinctions between certain assets to warrant the conclusion that the nature or character of the assets was fundamentally different. The Service stated that such assets should not be considered of a like kind, despite the fact that they were used in a similar activity. Accordingly, the National Office concurred in the agent’s conclusion that the taxpayer must establish that the assets are of a like class under Reg. Section 1.1031(a)-

2(b)(3) (providing for “Product Classes”). The Service stated: “[T]he issue of what constitutes like-kind property in the context of an exchange of personal property has not been the subject of much judicial review. In California Fed. Life Ins. Co. v. Commissioner, 680 F. 2d 85 (9th Cir.

1982), aff’g 76 T. C. 107 (1981), the Ninth Circuit affirmed the Tax Court’s determination that the exchange of Swiss francs for United States Double Eagle gold coins was not an exchange of like-kind property. The court concluded that ‘the Tax Court did not err in refusing to apply the lenient treatment of real estate exchanges to the exchange of personal property. Id. at 87.’ In addition to California Federal Life, the examples in the regulations provide some guidance on the issue of what constitutes like-kind property where the property is personal property. These examples consistently speak of exchanges of assets of the same type. Reg. Section 1.1031(a)-

2(b)(7). To the extent there are references to exchanges of assets of different types, i.e., an exchange of a grader for a scraper, the references are made in the context of demonstrating the use of General Asset Classes or Product Classes to determine whether assets are of a like class.

The examples do not suggest that different types of depreciable personal property would be considered like class or like kind.”

This FSA shows that the Service is likely to view the “like class” provisions as determinative, although the regulation refers to property either of a like kind or a like class. See Reg. Section

1.1031(a)-2(b)(1). As practitioners feared, the introduction to the personal property regulations may not be taken very seriously by the Service. Those provisions state that an exchange of properties of a like kind may qualify under Section 1031 regardless of whether the properties are also of a like class. Further, in determining whether exchanged properties are of a like kind, no inference is to be drawn from the fact that the properties are not of a like class. See Reg. Section

1.1031(a)-2(a).

The cases and rulings indicate that the courts and the Service have used a very limited and restrictive test in determining whether personal properties are of a “like kind.” Under the general like-kind test, personal properties deemed to be of like kind include the following:

1 Printing press for printing press [W.H. Hartman Co. v. Commissioner, 20 B.T.A. 302 (1930), acq. x-1 C.B. 27];

2. Car for car [Goggan & Bros. v. Commissioner, 45 B.T.A. 218 (1941); Joseph J. Vidmar, 11

TCM 854 (1952); John W. Snow, Jr., 12 TCM 1281];

3. Well equipment for well equipment [Laster v. Commissioner, 43 B.T.A. 159 (1940)];

4. Buses for buses [Commissioner v. North Shore Bus Co., Inc., 143 F.2d 114 (2d Cir. 1944)]

5. Trucks for trucks [Redwing Carriers, Inc. v. Tomlinson, 399 F.2d 652 (5th Cir. 1968);

National Outdoor Advertising Bureau, Inc. v. Helvering, 89 F. 2d 878 (2nd Cir. 1937)];

6. Construction and excavating equipment [Farish v. Commissioner, 4 T.C.M. 199 (1945)];

7. Dairy farm equipment [PLR 7837053 (June 16, 1978) exchange of dairy treated as seven exchanges of matched categories of dairy assets];

8. Oil and gas equipment [Rev. Rul. 68-186, 1968-1 C.B. 354];

9. Noncurrency bullion-type gold coins [Rev. Rul. 76-214, 1976-1 C.B. 218];

10. Gold bullion for Canadian maple leaf coin [Rev. Rul. 82-96, 1982-1 C.B. 113; but see

California Federal Life, supra (Swiss francs not of like kind to U.S. Double Eagle gold coins);

Rev. Rul. 82-166, 1982-2 C.B. 190 (gold bullion not of like kind to silver bullion); Rev. Rul. 79-

143, 1979-1 C.B. 264 (numismatic coins not of like kind to bullion coins)];

11. Steer calves for registered Aberdeen Angus livestock [Wylie v. U.S., 281 F. Supp. 180 (N.D.

Tex. 1968)];

12. Half-blood heifers for three-quarter blood heifers [Rutherford v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo

1978-505; but see Section 1031 (e) (livestock of different sexes are not of like kind)].

However, these cases and rulings, for the most part, simply assume or conclude without analysis that the personal properties are of a like kind without stating any general or definitive test. The only standard is the general definition of “like kind” set forth in the longstanding regulations:

“the words ‘like kind’ have reference to the nature or character of the property and not to its grade or quality.” Reg. Section 1.1031(a)-1(b). It is unclear what these words mean when applied to various items of personal property. Taxpayers will be forced to make many like-kind determinations in exchanges of hotels, restaurants and similar businesses. For example, many items of depreciable tangible personal property may be described in different Product Classes or in Product Classes ending in a “9.” In addition, the Product Classes may be used to distinguish industries based on manufacturing or materials, such as wood, metal, rubber, plastic, glass, etc.

The FSA indicates that the Service may take a very restrictive position in determining whether the assets are of like kind.

Corporations may also exchange significant amounts of intangible property, including patents, franchises, contract rights, customer lists, licenses and goodwill. The regulations provide that the determination of whether intangible property is of like kind generally depends on (1) the nature or character of the rights involved and (2) the nature or character of the underlying property to which the intangible property relates. Further, the regulations state that the goodwill or going concern value of two businesses is never of like kind. See Reg. Section 1.1031(a)-2(c).

Exchanges of intangible property that have been or would be allowed include exchanges of a copyright on a novel for a copyright on a different novel (but not for a copyright on a song), FCC radio license for FCC television license, major league sports contracts, Chamber of Commerce memberships, transferable mitigation credits, commodity exchange memberships, and airport landing rights or “slots”. The blanket prohibition on the exchange of the goodwill or going concern value of two businesses, irrespective of how similar the businesses are, is very controversial but the IRS has indicated its intent to enforce the regulation. See FSA 199951006

(“regulation is a valid exercise of agency discretion that should be sustained”); T.D. 8343

(Preamble) (1991). Compare FSA 1999-1162 (IRS would “prefer to litigate” the exchange of goodwill issue after the effective date of the regulation); Notice of Proposed Rule Making (IA-

12-89) 55 Fed. Reg. 17635 (1990). Under the above proposed regulations, the exchange of goodwill was not completely prohibited but only allowed in “rare and unusual circumstances.”

This prohibition may encourage taxpayers to classify and value its intangibles in creative ways and allocate the purchase and sale price to intangible properties other than goodwill.

Thus, corporations that exchange intangible properties will have very limited replacement property options. For example, the IRS issued a technical advice memorandum (TAM) that narrowly interpreted the “underlying property” in a television license to its assigned frequency of the electromagnetic spectrum in accordance with a prior TAM. TAM 200224004. See also TAM

200035005. The IRS ruled that the value of the FCC television license received in exchange for

FCC radio licenses did not include television network affiliation rights, as the taxpayer had contended. The taxpayer claimed that the ability to affiliate with a major television network was

not attributable to its existence as a separate asset but was inherent in the television license itself.

The IRS rejected this argument and stated that the appropriate manner of identifying the

“underlying property” is to look to the license itself and the license merely authorized the use of the radio transmitting apparatus.

The prior TAM approved an exchange of a radio license for a television license, finding the licenses to be of like kind under Reg. Section 1.1031(a)-2(c)(1). See TAM 200235005. The

TAM examined (1) the nature or character of the rights involved (finding the rights conferred on an FCC licensee to be basically the same, despite differences regarding the specific terms and conditions of operation with respect to radio and television licenses); and (2) the nature or character of the underlying property (finding the “underlying property” to be the assigned frequency of the electromagnetic spectrum referred to in each license). The TAM did not view the “underlying property” as the entire array of assets of a radio or television station or even as the tangible personal property referred to in the licenses, such as transmitters, towers and antenna, which are described in the same Product Class in the SIC Manual. The TAM noted that the FCC license principally relates to the use of the radio transmitting apparatus, rather than the apparatus itself. Although radio and television broadcasts are assigned to different frequency bands and have other differences, the TAM found these to be merely differences in grade or quality. The TAM stated that “even the narrowest interpretation of the like kind standard does not require that one property be identical to another or that they be completely interchangeable.”

Some commentators believe that under this test an exchange of broadcast television or radio licenses might be of like kind to cellular or satellite licenses, but that an exchange of broadcast television or radio licenses for cable television licenses will probably not be allowed.

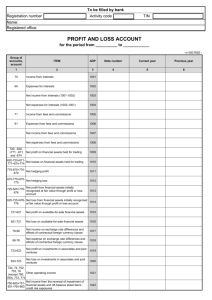

Financial Reporting Issues.

Almost all Section 1031 exchanges involving corporations or other taxpayers are treated as full recognition sales for financial reporting purposes. APB No. 29, Accounting for Nonmonetary

Transactions, requires such reporting for GAAP purposes because (i) almost modern exchanges are in fact “monetary transactions” whose amounts are fixed in terms of units of currency by contract or otherwise (this is especially true for deferred exchanges involving a QI’s sale of the relinquished property to a buyer) and (ii) even if the exchange qualifies as a “nonmonetary transaction, ” the fair values of the properties are determinable within reasonable limits and thus must be recognized for GAAP purposes. Opinion 29 states that “accounting for nonmonetary transactions should be based on the fair values of the assets (or services) involved which is the same basis as that used in monetary transactions. Thus, the cost of a nonmonetary asset acquired in exchange for another nonmonetary asset is the fair value of the asset surrendered to obtain it, and a gain or loss should be recognized on the exchange.” In general, only if the fair values of the assets transferred in a nonmonetary transaction are not determinable within reasonable limits would the gain or loss not be recognized for GAAP purposes. Thus, today’s Section 1031 exchanges are almost invariably treated as sales and purchases for GAAP purposes and then reclassified for tax purposes as exchanges in which recognition of the taxable gain or loss is deferred.

FASB Statement No. 153 was issued in December 2004 to further restrict the exceptions to recognition of gain or loss in nonmonetary transactions. The Statement amended Opinion 29 to

eliminate the exception for nonmonetary exchanges of similar productive assets and replaced it with a general exception for exchanges of nonmonetary assets that do not have commercial substance. A nonmonetary exchange has commercial substance if the future cash flows of the entity are expected to change significantly as a result of the exchange. Opinion 29 provided an exception to the basic measurement principle (fair value) for exchanges of similar productive assets. That exception required that some nonmonetary exchanges, although commercially substantive, be recorded on a carryover basis. The Statement eliminated the exception to fair value for exchanges of similar productive assets and replaced it with a general exception for exchange transactions that do not have commercial substance-that is, transactions that are not expected to result in significant changes in the cash flows of the reporting entity. By focusing the exception on exchanges that lack commercial substance, the Board believed that the Statement will produce financial reporting that more faithfully represents the economics of the transactions.

Since gain or loss on a Section 1031 exchange is recognized for financial reporting purposes but not for tax purposes, a book-tax difference arises. The replacement property is carried as an asset at its fair value (assets are debited), the book gain is credited to earnings, and a liability for deferred income taxes is credited. Debits equal credits. If the replacement property is subsequently sold in a taxable transaction, a tax-book difference arises. The book gain attributable to the relinquished property was already recognized for book purposes but now the tax gain must be recognized for tax purposes and the taxes must be paid. To pay the taxes, cash is credited and the liability for the deferred income taxes is debited. Credits equal debits. This is a very simplistic account of the book entries, and other adjustments and entries may be needed.