A9. The Not So Peaceful Pacific - International

advertisement

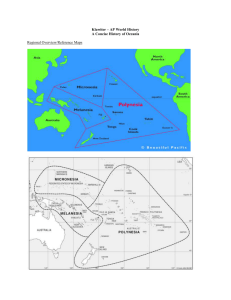

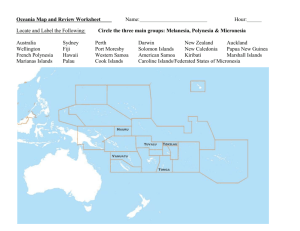

1 Australia and the Asia-Pacific Rosita Dellios © 2005 WEEK 9: THE NOT SO PEACEFUL PACIFIC As noted last week, the Pacific Ocean acquired its name from the Portuguese-born explorer Magellan when he crossed it in 1521. He called it Pacific because of the calm weather conditions he encountered. In contemporary times, the islands of the Pacific Ocean are often troubled. There have been coups in Fiji (May & Sept 1987, May 2000); a secessionist movement in Bougainville which, additionally, caused a mutiny in Port Moresby when the government hired mercenaries to solve the Bougainville problem; the post-1998 internal tensions in the Solomon Islands that resulted in a June 2003 Australian-led multinational police and military intervention to restore law and order; law & order problems also in Papua New Guinea which is deemed in 2004 to be on the brink of ‘failed state’ status 1 and which also has the Pacific region’s highest number of HIV/AIDS carriers (up to 50,000 sufferers in a population of 5.3m)2; anti-French and pro-independence sentiments in French Polynesia and New Caledonia, political violence in Palau, to name but the most turbulent of the USA’s Micronesian ‘quasi-empire’.3 Problems may be traced not only to relations among contending cultures (both intra-Pacific as well as indigenous and outsider), but also to geography and colonial history. Consider, for example, the following questions: Culture The 1200 languages of the Pacific Islands may be regarded as anchors into traditional cultures but also politically divisive for individual states and regional cohesion. Is this a Culture versus State dilemma? And if so, how would you deal with it if you were a local policy-maker? How and where have cultural/ethnic differences threatened state cohesion? Notable Quote: "Many of the island states have fragile economies and lack the economic resources to become viable independent states. And social and political developments have demonstrated the fundamental differences between political and economic modernity on the one hand and traditional practices on the other." 4 Geography In what ways does geography render the microstates of the Pacific politically vulnerable? (You might consider, for instance, the constraints of geographically determined economic factors and subsequent dependence on foreign aid.) Is geographic isolation from the mainstream of international affairs an advantage or a handicap or both? History What are some of the historical reasons for present-day political problems brought on by ethnic divisions? How has colonialism shaped contemporary politics and economics in the South Pacific Islands? Strategic Factors What has been the strategic attraction of this region to the USA? What is its strategic attraction to France? What about middle powers like Australia and New Zealand? In your view, what has been their real role and what is their ideal role? Notable Quote: 1 See Helen Hughes, Can Papua New Guinea Come Back From the Brink? Issue Analysis 49, 13 July 2004, The Centre for Independent Studies at http://www.cis.org.au/ (Refer also to Appendix 5) 2 Pacific Magazine, cited in The Weekend Australian, 10-11 July 2004, p. 23. 3 A term used in Timothy J. Gaffaney, ‘Linking Colonization and Decolonization: The Case of Micronesia’, Pacific Studies, Vol. 18, No. 2, June 1995 (pp. 23-59), P. 32. He explains the terms as “a relationship in which the mertropole determines the form of government, selects local government leaders, and controls some allocation of resources at the same time that it allows some degree of sovereignty in the periphery”. 4 Gen. Peter C. Gration, ADF, conference on the armed forces in Asia and the Pacific, ANU, Canberra, December 1989. 2 “. . . US interests in the islands has always been mainly military. Hawaii, whose independence was broken by a coup organized by American business and military interests, was then developed into the biggest US military base off the mainland. Guam, too, was converted into an enormous military basse (it was from there that much of the bombing of Vietnam was done) and American Samoa served as a naval base for more than half a century. Then at the end of the Second World War USA took the Mariana, Caroline and Marshall Islands by military action from Japan and is likely to maintain the controlling influence there for a long time.”5 More Specific Questions on Politics in the Pacific: How well organised are the microstates of the Pacific as a regional group? Identify the sources of political instability in (a) Fiji; (b) Papua New Guinea; (c) Solomon Islands Which Pacific Island states would fit the category of unstable and which could be described as areas of relative stability? Exercise: Issues of governance – A South Pacific Union? Read attached article: Benjamin Reilly, ‘Let’s Invite Islanders to Play in Our Backyard’, The Australian, 2 July 2004, p. 15. Form into small focus groups and design a “kind of European Union of the South Pacific”. Then join up as a class and compare results. Note that Governance & Development is the theme of a development conference that I will be attending in December 2005. Students are welcome to attend this conference too. The Fifth International Conference on the Governance and Development (IIDS), 1-4 Dec 2005 at the University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji www.usp.ac.fj/IIDS APPENDICES Appendix 1: The Countries within the 3 Regional Groupings & The Pacific Regional Forum (1) MELANESIA Melanesia includes: 1. the whole island of New Guinea and its lesser islands; 2. Solomon Islands; 3. New Caledonia; 4. Vanuatu; and 5. Fiji. (2) MICRONESIA Includes the Mariana, Marshall and Caroline island chains. Micronesia usually refers to: 1. Guam, a US territory in the Marianas, and to the islands of the dissolving UN Trust Territory which have emerged as the political units of: 2. the Republic of the Marshall Islands; 3. the Federated States of Micronesia - Yap, Chuuk (formerly Truk), Pohnpei and Kosrae; 4. the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariaras; and 5. the Republic of Palau (aka Balau). These islands experienced 5 decades of US control. (3) POLYNESIA The 11 political units making up Polynesia are: 5 Ron Crocombe, The South Pacific: An Introduction, 5th edn, University of the South Pacific, 1989, pp. 181-2. Hawaii was annexed by trhe USA in 1898, and formally became the 50th state of the Union in 1959. 3 1. the French Territory of Wallis and Futuna; 2. Tuvalu (independent); 3. the Kingdom of Tonga (which is the only surviving monarchy in the Pacific); 4. Western Samoa (the 1st Pacific country to become independent, in 1962); 5. American Samoa 6. Tokelau (made up of 3 small atolls); 7. Niue (the world's smallest microstate); 8. the Cook Islands (formally under NZ administration); 9. French Polynesia; 10. Hawaii (a US State); 11. Easter Island Pacific Islands Forum Sixteen countries from the Pacific region that come together every year to discuss issues that impact on the Pacific community. The Pacific Islands Forum has evolved into the only regional grouping of Pacific nations with the scope to discuss, develop and implement strategies that enhance the security, governance and sustainable development of its membership. It also provides a collective voice for the region in wider international settings.6 See also DFAT website for Pacific Islands Forum: http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/spacific/regional_orgs/spf.html Appendix 2: I. C. CAMPBELL, A History of the Pacific Islands, University of Canterbury Press Christchurch, New Zealand, 1989 Chapter THE POLITICS OF ANNEXATION Ten By 1900, all Pacific islands had fallen under the authority of foreign powers. This experience links the history of the Pacific islands with the history of Asia, Africa and the Americas, and there may therefore seem to be an inevitability of design about the outcome. Contemporaries certainly thought so; by the second half of the nineteenth century, Europeans at home and overseas, and those in the derivative states of America and Australasia, were intoxicated with sentiments of racial supremacy, and had devised crude philosophies to justify the political and material ascendancy to which they had risen. In the resulting atmosphere of imperialism, and particularly during the 1870s and 1880s, the major powers of Europe had assumed sovereignty over most of the peoples inhabiting the tropical parts of the world. In the Pacific, this apparent 'rush' for colonies was slightly delayed, occurring for the most part in the 1880s and 1890s, giving the appearance of being the final stages in a grand design; but in fact the Pacific islands did not become incorporated in the European empires as part of any grand design to partition the world, nor simply to give expression to an irrational European fantasy of racial superiority. There was a multiplicity of motives and a diversity of circumstances, with ample testimony, as usual, to both the noble and despicable characteristics of humanity, and the process extended fitfully not over two decades, but over six. In most cases it resulted from actual or threatened chaos occasioned by the uncontrolled, selfinterested contact between foreigners and islanders. New Zealand was the first island-group to fall to an extra-regional empire, annexed by Britain in 1840. Unlike Tahiti and Hawai'i, there had been no indigenous trend towards political centralization. in New Zealand. The wars of the 1820s and 1830s were purely destructive, pursued for the traditional concerns of prestige and revenge. Defeat of an enemy, while it led to the territorial dispossession of the defeated in some cases, was not followed by any consolidation of power or attempt to create a new dominance by one tribe, or of any supra-tribal polity. Consequently, the challenges posed by increasing European trade and settlement in the 1830s had to be met by Maori clans or tribes acting individually with neither common... 6 From Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade: Pacific Islands Forum 2003 ... Pacific Islands Forum. pac@mfat.govt.nz Pacific Islands Forum Special Leaders' Retreat ... URL: http://www.mft.govt.nz/foreign/regions/pacific/pif03/pifindex03.html 4 Appendix 3: Solomon Islands – The Failing State Our failing neighbour by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI). A paper on the Solomon Islands launched by the Hon. Alexander Downer on 10 June 2003 Extract from Ch. 3 What we see in Solomon Islands is a classic vicious circle. Weak institutions, corrupt governments, criminalisation of politics, poor law and order, insufficient revenue, economic stagnation, social dislocation, disaffected and alienated youth, a growing culture of violence, international neglect, collapse of government services, disillusioned and passive populations, and a plentiful supply of guns. Each of these elements reinforces the others to create a trap from which there appears no escape. On present trends it seems likely that the violence of 1998–2000 has fatally damaged a country that was already very fragile and in many ways barely functional. But there is hope. Many Solomon Islanders remain committed to making their country work. There is a ready acceptance of the need for deep reforms and big changes. There is also a ready acceptance of the need for help from outside on a larger scale than has been provided so far. Furthermore, there appears to be a recognition that help from outside will do nothing if the people of Solomon Islands themselves are not prepared to take responsibility for their own future. Appendix 4: Economic Stagnation July 2004 Pacific states stagnate Helen Hughes The Dominion Post Nearly all the Southwest Pacific islands have recorded another year of per capita income decline in 2003. The exceptions are Samoa, and modest growth in Fiji and Tuvalu. See The Centre for Independent Studies at: http://www.cis.org.au/ Appendix 5: Can PNG come back from the brink? After seven months of wrangling, arrangements to deploy more than 260 Australian police and other officials to Papua New Guinea have finally been made. In a paper to be released on Tuesday 13 July by The Centre for Independent Studies, Professor Helen Hughes argues that Papua New Guinea, in addition to restoring law and order, needs to implement economic reforms to put it on a growth path of the 7% a year needed to raise living standards. The report, Can Papua New Guinea Come Back From the Brink?, identifies the principal problems that face Papua New Guniea and outlines a reform agenda that would lead the country out of stagnation. Two major new resource projects are currently being negotiated in Papua New Guinea - the Ramu nickel/cobalt mine to be developed by the Chinese government and the on-again, off-again 4,000 kilometres gas pipeline from Papua New Guinea's Southern Highlands to Queensland. 'Such resource projects are important, but they should be seen as the icing on the cake of labour-intensive agriculture, tourism and manufacturing that would provide the jobs and income needed to meet the aspirations of a young and growing population.' Hughes warns that these new mineral projects may even be counter-productive because they reduce the pressure on the government to reform. Good weather and high primary product prices have given the Somare government an opportunity to improve economic performance. But political maturity is essential if new mineral incomes are to be harnessed constructively. In an age of globalisation when human capital (education and health) is vital, Papua New Guinea's social sectors are in dire straits and it has lost a generation to underemployment and crime. 5 'Education funding like health funding, seems designed to ensure minimal administrative efficiency and maximum opportunities for waste and theft. "Leakages" of funds are substantial.' As the largest donor to Papua New Guinea, Australia contributed more than $A300 million of aid annually between 2000-01 and 2003-04, but Australian aid was not able to stem the decline in roads, education and health. Australia's new, enhanced aid programme is thus designed to address some of the basic issues in law enforcement and administration. The budget for 2004-05 is $4.2 million. At this level of support Australian aid to Papua New Guinea would be over $2 billion over the next five years. 'This aid can only succeed in a framework of "mutual obligation" in which, in return for financial assistance, the Papua New Guinea Government pursues reforms that will remove the roadblocks to growth.' Helen Hughes is Professor Emeritus at the Australian National University, and a Senior Fellow at CIS. She is available for comment. Copies of the paper are available here ENQUIRIES For more information, please contact: Nina Blunck Public Affairs Officer The Centre for Independent Studies t: 02 9438 4377 e: media@cis.org.au www.cis.org.au Appendix 6: The Economic Importance of the Marine Environment The marine environment is traditionally the economic lifeline of Pacific island communities. Today, fish is still the most valuable resource of the island states. It remains a major source of their income, and it is one of the few renewable resources. South Pacific island nations claim over 60 million sq km as exclusive economic zones (EEZs). In effect, each nation claims marine resources within 200 nautical miles out to sea beyond the last dry land. In cases of overlapping claims - say between 2 nations - they have exactly half the waters. Licensed fishing by foreign vessels in these zones provides revenue to the island states. However, it should be noted that fisheries income obtained mainly through leasing sovereign waters rather than through owning fishing fleets usually amounts to less than 5% of the value of the catches. Appendix 7: French Polynesia Extract from NZ Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Trade: http://www.mft.govt.nz/foreign/regions/pacific/country/frenchpolynesiapaper.html#General Tahiti became the first island in the Pacific to come under the control of a foreign power and was made a French Protectorate in November 1842. The French Protectorate continued until 1880 when King Pomare V abdicated and a French colony was proclaimed. By 1901 the French colony in Tahiti incorporated all of the Society Islands as well as the Marquesas Islands, Austral Islands, and the Tuamotu Archipelago. Today, descendants of the Tahitian “royal” family, Pomare, press claims for lost rights but to little practical effect. Political Situation Following the end of the Second World War, indigenous nationalism began to develop under the leadership of Pouvana’a a Oopa. With the support of war veterans, Pouvana’a pressed for equal rights for Polynesians under French law. In 1945 all Tahitians were granted French citizenship. The French Government also established the first territorial assembly in 1946 with 30 elected members. In July 1957 6 the territory was reconstituted “French Polynesia”, broadening the assembly’s responsibilities and creating a government council of 6-8 ministers. In 1984 French Polynesia’s powers of self-government were enhanced by the passage of the Statute of Autonomy. This allowed French Polynesia to have its own flag and anthem alongside the emblems of the French Republic. The President also acquired chief executive powers and new areas of responsibility. The regulatory powers of the Council of Ministers were extended as well. Since 1984 French Polynesia has celebrated Autonomy Day on 29 June, although the date is not without controversy, being also that of French Polynesia’s annexation by France. Further revisions were made to the Statute in April 1996, transferring additional responsibilities over to French Polynesia (eg territorial budget, health, primary education, social welfare, public works, agriculture) as well as a greater say over external trade, international airline and shipping links, exploitation of lagoon and EEZ marine resources, and the possibility of negotiating specified regional or international agreements. The French constitution is currently being amended to provide for decentralisation of competencies from the centre to the departments and to overseas “communities.” Economic Situation French Polynesia’s economy is characterised by a narrow export base and its dependency on French financial aid. The high reliance on France as a critical source of income has distorted the economy, creating a high cost of living (with a growing income disparity), an inflated public sector, high wage costs and a decline in primary production. French Nuclear Testing In June 1996, France ended thirty years of nuclear testing in the atolls of Mururoa and Fangataufa. The testing sites have since been dismantled, the surrounding military structure disbanded, and only a small contingent remains stationed on Mururoa for purposes of radiological monitoring. French Polynesia is adjusting to a reduced inflow of French funds. Easing this adjustment is a ten-year funding package of NZ$300 million a year, 1996-2005, calculated to compensate the Territory for testingrelated spending and targeted at encouraging greater economic self-sufficiency. This French aid package is in addition to the 1994-2003 Pact of Progress (NZ$1 billion in the first five years), since extended to 2006, designed to compensate for the earlier 1992-1995 testing moratorium. The rewewed “Reconversion Fund” was signed in October 2002 by Prime Minister Raffarin and President Flosse, continuing indefinitely the transfer of 150 million euros per annum to French Polynesia Foreign Relations Under the French Constitution, France is responsible for conducting foreign relations on behalf of French Polynesia. France represents French Polynesia in international bodies such as the United Nations and the World Trade Organisation (WTO). However, French Polynesia’s regional links in the Pacific have been growing in recent years to reflect its constitutional status as an autonomous territory.