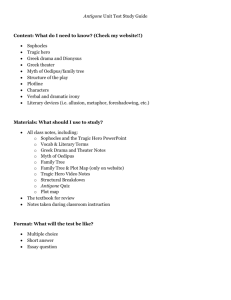

Terminology for Greek Drama

advertisement

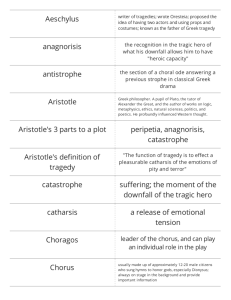

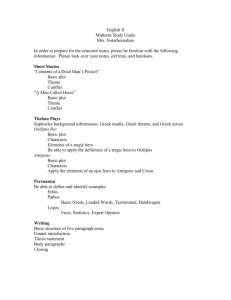

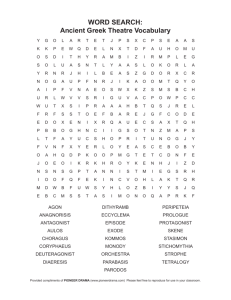

Terminology for Greek Drama Tragoedia: The tragedy of the ancient Greeks as well as their comedy confessedly originated in the worship of the god Dionysus. It is proposed in this article (1) to explain from what element of that worship Tragedy took its rise, and (2) to trace the course of its development, till it reached its perfect form and character in the drama of the Attic tragedians, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides Aristotelian Definition of Tragedy Aristotle defined tragedy as "the imitation of an action that is serious and also, as having magnitude, complete in itself." It incorporates "incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish the catharsis of such emotions." The tragic hero will most effectively evoke both our pity and terror if he is neither thoroughly good nor thoroughly evil but a combination of both. The tragic effect will be stronger if the hero is "better than we are," in that he is of higher than ordinary moral worth. Such a man is shown as suffering a change in fortune from happiness to misery because of a mistaken act, to which he is led by his hamartia (his "effort of judgment") or, as it is often literally translated, his tragic flaw. One common form of hamartia in Greek tragedies was hubris, that "pride" or overweening selfconfidence which leads a protagonist to disregard a divine warning or to violate an important law Trilogy: Three plays performed in sequence; the basic pattern of ancient Greek tragedies, of which one - Aeschylus' The Oresteia (Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides) is still extant. Satyr play: The fourth play in a Greek tetralogy. Satyr plays were short bawdy farces that parodied the events of the trilogies that preceded them. Orchestra: The circular area that functioned as a stage for action in Greek theater. In the Roman theater, scene structures and built up stages were created for the action, and the circular orchestra was thus truncated to a semi-circular area. Chorus: A group of actors in Greek drama who comment on the action of the play. The role of the chorus came directly from drama as religious ritual and dates from a time when there were no individual actors. What the chorus says about the action reflects the traditional values of ancient Greek culture. Chorus members chanted their lines together and moved as a unit from side to side on the stage. Theatron: originally referred to the "watching space" of the Greek theater, but later became synonymous with the entire auditorium consisting of the spaces for both the audience as well as the performance. Skene: a low building (made of wood in the fifth century, made of stone later) behind the orchestra. The skene served both as a changing house for the actors and as a background to the drama. The area in front of the skene used for some of the dramatic action is the proskenion (from which the modern term, “proscenium” derives). Parados: The ode sung by the chorus entering the orchestra in a Greek tragedy; the space between the stage house (skene) and audience seating area (theatron) through which the chorus entered the orchestra. Thespis: Although some scholars doubt his historicity, he was probably an Athenian playwright (c. 534 BC), known as the father of drama for having created the first role for an actor. Aeschylus: Aeschylus (525—456 BC; Greek: Αισχυλος) was a playwright of ancient Greece. Aeschylus was the earliest of the three greatest Greek tragedians, the others being Sophocles and Euripides. Sophocles: Sophocles (early 5th century–406 BC; Greek: Σοφοκλης) was an ancient Greek playwright, dramatist, priest, and politician of Athens. He is known as the second, chronologically, of the three great Greek tragedians; Sophocles was several decades younger than Aeschylus and a decade or so older than Euripides, and was often in competition with both in dramatic contests. Structure of a Greek Play: Prologue: In Greek tragedy, a speech or brief scene preceding the entrance of the chorus and the main action of the play, usually spoken by a god or gods. Subsequently, the term has referred to a speech or brief scene that introduces the play. Parode: (Entrance Ode): The entry chant of the chorus, often in an anapestic (short-short-long) marching rhythm (four feet per line). Generally, they remain on stage throughout the remainder of the play. Although they wear masks, their dancing is expressive, as conveyed by the hands, arms and body. Ode: A classical Greek poem modeled on the choric ode and usually having a three-part structure consisting of a strophe, an antistrophe, and an epode. Stasimon: In the Greek tragedy, a song of the chorus, continued without the interruption of dialogue Episode: 4. Greek Theaters Greek tragedies and comedies were always performed in outdoor theaters. Early Greek theaters were probably little more than open areas in city centers or next to hillsides where the audience, standing or sitting, could watch and listen to the chorus singing about the exploits of a god or hero. From the late 6th century BC to the 4th and 3rd centuries BC there was a gradual evolution towards more elaborate theater structures, but the basic layout of the Greek theater remained the same. The major components of Greek theater are labeled on the diagram above. Orchestra: The orchestra (literally, "dancing space") was normally circular. It was a level space where the chorus would dance, sing, and interact with the actors who were on the stage near the skene. The earliest orchestras were simply made of hard earth, but in the Classical period some orchestras began to be paved with marble and other materials. In the center of the orchestra there was often a thymele, or altar. The orchestra of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was about 60 feet in diameter. Theatron: The theatron (literally, "viewing-place") is where the spectators sat. The theatron was usually part of hillside overlooking the orchestra, and often wrapped around a large portion of the orchestra (see the diagram above). Spectators in the fifth century BC probably sat on cushions or boards, but by the fourth century the theatron of many Greek theaters had marble seats. Skene: The skene (literally, "tent") was the building directly behind the stage. During the 5th century, the stage of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was probably raised only two or three steps above the level of the orchestra, and was perhaps 25 feet wide and 10 feet deep. The skene was directly in back of the stage, and was usually decorated as a palace, temple, or other building, depending on the needs of the play. It had at least one set of doors, and actors could make entrances and exits through them. There was also access to the roof of the skene from behind, so that actors playing gods and other characters (such as the Watchman at the beginning of Aeschylus' Agamemnon) could appear on the roof, if needed. Parodos: The parodoi (literally, "passageways") are the paths by which the chorus and some actors (such as those representing messengers or people returning from abroad) made their entrances and exits. The audience also used them to enter and exit the theater before and after the performance. 5. Structure of the plays read in Humanities 110 The basic structure of a Greek tragedy is fairly simple. After a prologue spoken by one or more characters, the chorus enters, singing and dancing. Scenes then alternate between spoken sections (dialogue between characters, and between characters and chorus) and sung sections (during which the chorus danced). Here are the basic parts of a Greek Tragedy: a. Prologue: Spoken by one or two characters before the chorus appears. The prologue usually gives the mythological background necessary for understanding the events of the play. b. Parodos: This is the song sung by the chorus as it first enters the orchestra and dances. c. First Episode: This is the first of many "episodes", when the characters and chorus talk. d. First Stasimon: At the end of each episode, the other characters usually leave the stage and the chorus dances and sings a stasimon, or choral ode. The ode usually reflects on the things said and done in the episodes, and puts it into some kind of larger mythological framework. For the rest of the play, there is alternation between episodes and stasima, until the final scene, called the... e. Exodos: At the end of play, the chorus exits singing a processional song which usually offers words of wisdom related to the actions and outcome of the play. Strophe: In Greek choruses and dances, the movement of the chorus while turning from the right to the left of the orchestra; hence, the strain, or part of the choral ode, sung during this movement. Also sometimes used of a stanza of modern verse. Antistrophe: In Greek choruses and dances, the returning of the chorus, exactly answering to a previous strophe or movement from left to right. Hence: The lines of this part of the choral song. It was customary, on some occasions, to dance round the altars whilst they sang the sacred hymns, which consisted of three stanzas or parts; the first of which, called strophe, was sung in turning from east to west; the other, named antistrophe, in returning from west to east; then they stood before the altar, and sang the epode, which was the last part of the song. Aristotle Theories: Six elements of Tragedy: plot, characterization, thought, diction, music, and spectacle Tragic hero: Definition of a Tragic Hero A tragic hero has the potential for greatness but is doomed to fail. He is trapped in a situation where he cannot win. He makes some sort of tragic flaw, and this causes his fall from greatness. Even though he is a fallen hero, he still wins a moral victory, and his spirit lives on. TRAGIC HEROES ARE: BORN INTO NOBILITY: RESPONSIBLE FOR THEIR OWN FATE ENDOWED WITH A TRAGIC FLAW DOOMED TO MAKE A SERIOUS ERROR IN JUDGEMENT EVENTUALLY, TRAGIC HEROES FALL FROM GREAT HEIGHTS OR HIGH ESTEEM REALIZE THEY HAVE MADE AN IRREVERSIBLE MISTAKE FACES AND ACCEPTS DEATH WITH HONOR MEET A TRAGIC DEATH FOR ALL TRAGIC HEROES THE AUDIENCE IS AFFECTED BY PITY and/or FEAR Hamartia: hamartia (his "effort of judgment") or, as it is often literally translated, his tragic flaw. Hubris: One common form of hamartia in Greek tragedies was hubris, that "pride" or overweening self-confidence which leads a protagonist to disregard a divine warning or to violate an important law Mimesis: The imitation or representation of aspects of the sensible world, especially human actions, in literature and art. Catharsis: A purifying or figurative cleansing of the emotions, especially pity and fear, described by Aristotle as an effect of tragic drama on its audience. Freytag’s Triangle—1863 In his book Technique of the Drama (1863), The German critic Gustav Freytag proposed a method of analyzing plots derived from Aristotle's concept of unity of action that came to be known as Freytag's Triangle or Freytag's Pyramid. In the illustration above, I have borrowed from both critics to present a graphic that can be employed to analyze the structure and unity of a narrative's plot. The Greek Labels: Desis: Desis is everything leading up to the moment of peripeteia. Lusis: lusis is everything from the peripeteia onward (denouement). Peripeteia: The reversal of the situation in the plot of a tragedy is the peripeteia. According to Aristotle, the change of fortune for the hero should be an event that occurs contrary to the audience's expectations and that is therefore surprising, but that nonetheless appears as a necessary outcome of the preceding actions. Anagnorisis: Anagnorisis is the recognition by the tragic hero of some truth about his or her identity or actions that accompanies the reversal of the situation in the plot, the peripeteia. Oedipus's realization that he is, in fact, his father's murderer and his mother's lover is an example of anagnorisis. Catharsis: Aristotle describes catharsis as the purging of the emotions of pity and fear that are aroused in the viewer of a tragedy. Debate continues about what Aristotle actually means by catharsis, but the concept General Literary Terms: Point of Attack: that moment nearest the beginning of the play in which the major conflict to be resolved occurs, sometimes called the inciting moment. In Medias res: (Latin: "In the middle[s] of things") The classical tradition of opening a story not in the chronological point at which the sequence of events would start, but rather at the midway point of the story. Later on in the narrative, the hero will recount verbally to others what events took place earlier. Usually in medias res is a technique used to heighten dramatic tension or to create a sense of mystery. Antecedent action: everything that has happened before the play begins Visible Action: Invisible Action: Parallel Scene: Deus ex Machina: Literally, "god out of a machine," a literary or staging device which refers to some last-minute salvation of a tricky situation by a god or goddess who has been watching the entire plot unfold from afar. In the baroque period, elaborate scenery was devised whereby a particular god (more often than not Amor, the god of love) would descend from above the stage in a little cloud or carriage. Allegory: a figurative mode of representation conveying a meaning other than and in addition to the literal. Foil: A foil character is either one who is in most ways opposite to the main character or nearly the same as the main character. The purpose of the foil character is to emphasize the traits of the main character by comparison or contrast. Paradigm: From the Greek word paradhma (paradigma), the term paradigm was introduced into science and philosophy by Thomas Kuhn in his landmark book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962). Essentially, a paradigm is simply the predominant worldview in the realm of human thought. For instance, today we would say that we live within an evolutionary paradigm since evolution is the predominant worldview regarding origins. Verisimilitude: Literally, the appearance of truth. In literary criticism, the term refers to aspects of a work of literature that seem true to the reader. Verisimilitude is achieved in the work of Honore de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert, and Henry James, among other late nineteenth-century realist writers. Ambiguity: The existence of several possible meanings, including conflicting attitudes or feelings. For the formalist critic ambiguity may not be a weakness but a virtue of the text as it reflects a richness or complexity of meaning in the literary work. In Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), William Empson defines variant types of ambiguous language that can be identified in literature and used to explore its meaning. Mimetic Theory of Art: Art is essentially an imitation of Nature.