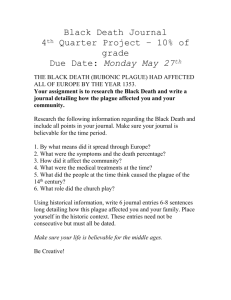

the black death and the peasants' revolt

advertisement

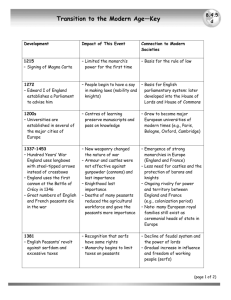

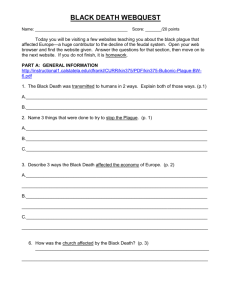

THE BLACK DEATH AND THE PEASANTS’ REVOLT by Leonard Cowie Chapter One: A Troubled England P11 BD produced important social changes. English society was based upon the principle that there were three main classes of people, each with its own purpose to fulfil. These were the clergy, the nobility and the peasants – those who prayed, fought and worked. The peasants (free people who could move around) were the largest group and it was accepted that they supported the other two classes by their labours. The church and nobility owned great estates to which the peasants were bound as serfs (could not leave the land of their lord) – by custom to plough the fields for the masters – by law. Serfdom was upheld by moral and religious reasons. Serfs were told to look upon their service as a calling from God. Serfdom would make people better. P13 Landlords were supposed to look after their serfs but many did not. When one lord was rebuked for taking a cow from a serf he said: “Let it suffice that the boor that I have left him the calf and his own life.” ** Medieval society was marred by a streak of cruelty and callousness. Death and suffering were common and people often felt contempt for the law and would often resort to violence. P17 Medicine was crude and often ineffectual. Medicine was mixed up with magic and ritual was common. Disease was often regarded as God’s judgement for sin. Falling ill was a punishment for past misdeeds. Chapter Two: The Plague from the East P19 The Black Death originated in the east. During 1346 rumours reached Europe that bad things were happening in the east. It was commonly thought that plague was caused by corrupted air. It was thought that this miasma had been drawn up from the depths of the ocean into the air. P22 Word came from the east about the plague – but it was unsubstantiated and caused little alarm. The plague came to Europe via the trade routes. P23 By 1348 plague had reached Sicily and then to Italy. Ships from the east tried to make landing at Genoa but were forced back to sea. The first symptoms were the buboes or swellings in the lymph nodes – under the arms and in the groin and neck – some as large as an apple or an egg. The infection then spread and changed. P24 Black spots appeared on the arms or legs – small and large – few and numerous. Some writers noted changes in the disease which was pneumonic plague which appeared in the winter months and stopped in the spring. P25 Despite medical beliefs that the plague was spread by air, people soon noted that it was spread through contact with the infected person or anything that they had touched. 1 P27 The plague took its toll on both the just and unjust. No amount of prayer and penance could stop the plague. People became obsessed with death. Chapter Three: The Black Death in Europe In Florence some people sequestered themselves in walled communities to try and stay safe. They ate and drank modestly and avoided luxury and distracting themselves with music and conversation. P32 Other people became reckless in the face of death. They allowed strangers into their houses. There was no-one left to enforce any laws. Everyman was free to anything he liked. Some tried to ward off infection, others fled the city. People carried flowers and herbs and spices which the sniffed to try and keep out the smell of death and decay. People avoided each other. Children were sometimes abandoned to their fate by their parents. P33 The dead were hurried to their graves without customary burial rites. P34 Death came swiftly and neighbours often dragged decaying neighbours into the street. Funerals often ceased to exist. Consecrated ground was used up and large pits were dug instead. “And there were so many dead throughout the city who were so sparsely covered with earth that the dogs dragged them forth and devoured their bodies.” People expected each day to be their last. Upwards of 100,000 people died in Florence. P38 Manors, castles, stately homes were empty. Aristocratic families were wiped out. Young people who were alive in the morning were often dead by nightfall. P39 The plague reached France 1348-9. The young were more afflicted than the old. As the plage spread to Germany and other countries there appeared religious fanatics called Flagellants who whipped themselves into a frenzy to avert God’s wrath Chapter Four: England Infected P41 Plague reached the Dorset coast in August 1348. Some people were well in the morning and dead by lunchtime. No-one who contracted the disease lived more than 3-4 days. King Edward lll wrote to the Governor of Jersey telling him to forgive the fishermen the tax they usually paid to the king. P42 People suspected that the infection was spread by the breath of infected people. P43 1349 was the worst year. Between a quarter and a third of the population did not survive. In January 1349 it was noted by the Bishop of Bath that many people were dying without the Last Rites being performed and that his remaining priests should, “…publicly command and persuade 2 all men…that, if they are on the point of death and cannot secure the services of a priest, then they should make confession to each other…whether to a layman or, if no man is present, then even to a woman.” P45 Plague reached London. It was a dirty city even though there had been moves to clean it up since 1309 by prohibiting people from dumping sewage and rubbish in the streets and instead they should dump it in the Thames. Fines were to be imposed on those who did not obey. P46 People who had dung in front of their houses were also to be fined – as well as those people who left dung outside other people’s houses. About 30,000 out of a population 70,000 died in London. P48 Some people suffered from abscesses all over their body and if they had them lanced they had a chance of survival. But those who had small black pustules almost never survived. Many villages were totally wiped out. A group called the Flagellants came to London as the plague was waning and held their public demonstrations in front of St Paul’s Cathedral. They were soon deported as undesirable aliens. Chapter Five: Prayer and Despair P50 As the plague subsided it was obvious that there were too few people to carry out the work. The summoning of Parliament was postponed twice during 1349. P53 There were scarcely enough of the living to bury the dead. Monasteries were particularly hard hit because of the close living quarters. The pestilence was immediately followed by a pestilence among beasts. Lands were uncultivated and animals were untended. P56 Medieval people did not keep statistics and often figures were exaggerated. P57 As the plague swept north the Scots decided to attack the English. But the Scots got the plague as well. 1350 was a bad year for Scotland as they suffered the full force of the Black Death. By the end of 1350 there was scarcely anywhere in Britain that did not have the plague. Families were broken; communities shattered. English society itself had been shaken to its very foundations. Chapter Six: A Changed Society P59 There was a hope that those who had survived were in God’s grace. That somehow they would be more tolerant and full of love and charity. “But no sooner had the plague ceased than we saw the contrary.” People gave themselves up to gluttony, games of hazard, unbridled lechery, strange fashions and indecent manners. People displayed, not their best qualities but their worst. They thought there would be an abundance of everything since the population had dropped. In some countries there was famine. 3 P60 Most commodities were more costly – twice the price of before the plague. Law suits and disputes increased. Villages were robbed and pillaged. P61 Labourers wanted more money and priests left their stipends – seeking more money elsewhere. People’s immortal souls were in danger. Many priests had died and there followed an influx of middle-aged widowers seeking to be priests. Many were ordained but many were illiterate although some could read but with little understanding of what they were reading. P62 The Archbishop of Canterbury tried to insist that priests serve their own church and be moderately paid. Most teachers were clerics which brought about huge changes in English education. School children had been educated in Norman French which was not a procedure followed in other countries. But with so few left who could speak French, students had to be taught in English. P63 By 1385 children in all the grammar schools in England were taught in English. This was considered a disadvantage for young men who might want to work and travel abroad. P64 1362 a law was passed ordering law courts to use English instead of French. Many poorer people had been disadvantaged by not speaking French. It was thought people would be more law abiding if they understood the laws in English. All written work in courts was to be in Latin. New universities were set up to fill the gaps. P66 There was a great shortage of labour. Horse 40/- now half a mark Fat ox now 4/Cow 12d Heifer 6d Fat wether 4d Sheep 3d Lamb 2d Large pig 5d Stone of wool 9d Sheep and ox strayed over lands and among crops. There was not enough labour to bring in the crops as they were – even when there were higher wages. Crops rotted in the fields. Landlords began competing for tenants and labourers and had to offer better terms. P67 Many buildings fell into disrepair. “In the following winter there was such a dearth of servants for all sorts of labour as it was believed had never been seen before. For the sheep and cattle strayed in all directions without herdsmen, and all things were left with none to care for them.” Lords often remitted rents to half or 1-3 years to prevent their tenants leaving. P68 It became common for tenants to have a reduced rent until the landlord could find someone willing to pay more. Other lords charged a higher rent but remitted some of the feudal duties. 4 Chapter Seven: Peasant Discontent Lords complained that there were three things that were not good when they were out of control; water flood, wasting fire and the common multitude of small folk. “For the poor and small folk, who should cleave to their labour, demand to be better fed than their masters. Moreover, they bedeck themselves in fine colours and fine attire, whereas (were it not for their pride and privy conspiracies) they would be in sackcloth of old.” (John Gower, small landowner) Gower also complained about the demand for higher wages. He lamented the loss of the good old days when peasants were ‘content’ with drinking water and not eating wheaten bread. And when they considered eating bread and milk to be a feast. “Now they work little, dress and feed like their betters, and ruin stares us in the face.” P72 King Edward lll did try to address the problem of wages. In 1349 a statute was passed forcing the able-bodied to work and to fix wages at their 1346 level. In 1351 – the first Parliament since the plague passed the Statute of Labourers. This defined the labour laws. Lords were instructed not to pay more than they had previously. But it was not easy to get labour at all and higher wages were paid. P73 The King fined lords who had given higher wages. He also tried to restrain the peasants by arresting them. Many seemed to have escaped prison and fled to the forests. Others were freed when they promised not to take the higher wages. Many labourers refused to accept salt meat instead of fresh meat and to eat yesterday’s cabbage. They resented the King for making the Statute. There was some sympathy for peasants who were expected to agree to low wages while prices rose. P75 Langland sympathised with the poor and he attacked the greed of the landlords. Tensions rose further in the land when in 1377 Edward lll died and ten-year-old Richard ll became the king. In his first Parliament it was noted that serfs were refusing to work for their lords and may be conspiring to revolt. Chapter Eight: John Wycliffe and John Ball P77 The peasants were reaching flashpoint and were further inflamed by Wycliffe (1325-84). He wished to reform the church. He called on the church to give up its property and live in poverty to assist the poor. He also denied that the pope could excommunicate anyone, and that the King or church could not give land in perpetuity. He sent out ‘Poor Priests’ called Lollards to preach to the people. His words were quickly misconstrued by his preachers and he had to quickly deny that peasants could refuse to serve their lords. P78 He did criticise lords who ripped off their workers. The chief agitator on behalf of the peasants was a priest called John Ball. It was commonly thought that Ball was a follower of Wycliffe. He spoke against the lords and the clergy and he had the support of the common people. He believed that tithes should come from the rich. 5 P79 He had been forbidden to preach in churches and so he preached in the streets and villages and fields. The church often condemned him and he was often thrown in jail. Ball preached, “My friends , the state of England cannot be right until everything is held communally, and until there is no distinction between nobleman and serf, and we are all as one.” P80 “They are dressed in velvet and furs, while we wear only cloth. They have wine, and spices and good bread, while we have rye, and straw that has been thrown away, and water to drink. They have fine houses and manors, and we have to brave the wind and rain as we toil in the fields. It is by the sweat of our brows that they maintain their high state…Let us go to the King...When the king sees us, either he will listen to us, or we will help ourselves.” By 1381 Ball had gathered many supporters. He called for a march on London. Some in London began to hear about the peasants’ grievances and thought that all the silver and gold was in the hands of the rich and that the country was badly governed. They began to send word to the counties to come at one to London where they “…would press the King so hard that there would not be a slave left in England.” The messages, sent to villages in Essex and Kent, contained codewords that would be understood by Ball’s followers. P82 The peasants were on the brink of rebellion. Peasants began to say that their servitude was excessive and in the beginning of the world no man was a slave. In 1358 there had been a peasant (Jacquerie) rebellion in France. Chapter Nine: The Flame of Rebellion P85 The immediate cause of the Peasant’s Revolt was a Toll Tax. They were graduated by wealth and rank. Three were implemented between 1377 and 1380. Everyone was to pay 3 groats and the rich to pay not more than 60 groats and none less than 1 groat. Tax commissioners were to be employed to collect the tax. P86 Widespread tax evasion took place. Lists of eligible taxpayers were to be made and the commissioners had to bring the tax (less their cut) to the Exchequer. Tax evaders were to be arrested and punished. The Revolt itself began on the 30th May 1381. A tax commissioner named Thomas Bampton summoned men from three villages; Fobbing, Corringham and Stanford to Brentwood to ask them who had been evading tax. Thinking they had not paid, he wanted a new tax. The people of Fobbing had a receipt for the tax they has already paid and they refused to pay more. The men of Fobbing were joined by the other two villages and they all gathered together and refused to pay more. Thomas Bampton ordered their arrest but the people resisted and threatened to kill Bampton and his sergeants. Bampton fled to London. The villagers fled to woods and his until they were too hungry to stay longer. They then went about to other villages to get support. P87 The King sent Sir Robert Belknap, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, into Essex to restore order. He swore in local people to speak against the villagers who had refused to pay more tax. The 6 villagers went to speak to him and told him he was a traitor and that he was telling lies about the tax. They made him swear on the Bible that he would never hold such a session again. They made him give them a list of names of those who had spoken against them. They caught as many as possible and cut their heads off and tore their houses down. Sir Robert fled. By this time there were around 50,000 disgruntled villagers and they went to manors and townships and those who would not join them had their homes torn down. They caught three clerks of Thomas Bampton and cut their heads off and carried them on poles for several days. They were now determined to kill all lawyers, jurors (special witnesses who had knowledge of the case and could speak against others), and servants of the King. The flame of revolt spread through Essex. The men called for all able bodied men to join them and demand their freedom. They threatened that those who did not come and help would be punished. ‘ P88 The Essex rebels sent messages to the people of Kent. They rose up too and stopped all pilgrims on the road to Canterbury to swear allegiance to the King and Commons and that they would join the rebellion when needed and that they would not consent to raising any new taxes. The rebels in Kent released all prisoners from jail, including John Ball. P91 The Kentish rebels decided to march on London. On the 10th June 1381 they were joined by Wat Tyler and Jack Straw. They were going to demand that no Englishman should remain a serf. They sent word to other counties to come to London and thereby surround London. Another group attacked Rochester Castle and seized the governor, Sir John Newton who was coerced into becoming their commander-in-chief. The mob marched to Blackheath burning and lootingespecially lawyers’ homes for enforcing the Statutes of Labourers. Thousands of peasants waited just outside London for the King. Meanwhile Richard was lodged in the Tower for safety with 600 of his advisers and Council. Chapter Ten: March and Massacre Sir John Newton was sent to the king with a message requesting a meeting at Blackheath the next day. 60,000 rebels were stirred up by John Ball that night: When Adam delved and Eve span Who was then the gentleman? He wanted them to kill the lords then the lawyers, justices and jurors, and anyone else who might be harmful to the community in the future. The people called out that he should be Archbishop and Chancellor and that the Archbishop should be executed. P96 The King arrived to speak to the rebels on his barge. But the royal party, feeling unsafe, did not stay long and soon departed. The Earl of Salisbury called out: “Gentlemen, you are in no fit state nor are you properly dressed to speak to the King.” P98 The mob then attempted to get in to London – destroying homes on the way and releasing prisoners from Marshalsea Prison. The bridge was closed to them but sympathisers inside the city opened the gate and let them in. Peasants from Essex Kent, Sussex and Bedford entered London led by War Tyler and Jack Straw and John Ball. All of London was in terror. They destroyed the Palace of Savoy, the home of John of Gaunt, the King’s uncle. P99 They ransacked the Temple and destroyed documents that listed feudal dues. At night they camped around the Tower. Richard could see the fires from the Tower. His advisers had little 7 advice for him. He ordered that it be cried out that all every man between fifteen and sixty should go to Mile End where the King would meet them at seven o’clock. P101 As the King exited the Tower 400 rebels led by Tyler, Straw and Ball dashed in and created havoc. They murdered Simon Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury who was a Lord Chancellor and had introduced the Poll Tax. P102 They also beheaded Sir Robert Hales at Tower Hill. They killed many prominent citizens and Flemish weavers who were thought to be sending gold out of the country. Chapter Eleven: King Richard and Wat Tyler The King made his way to Mile End where 60,000 men had assembled. “My friends, I am your King and your lord. What do you want? And what do you wish to say?” Those who heard him replied: “We want you to set us free for ever, us and our descendants and our lands, and to grant that we should never again be called serfs, nor held in bondage.” The King promised them what they wanted and arranged to have it drawn up in writing. He promised a banner for: Kent, Essex, Bedford, Cambridge, Stafford and Lincoln. He gave a free pardon to the people of the counties if they returned home. Half the mob dispersed and thirty secretaries drew up the letters. P105 However, many of the peasants refused to leave. Tyler, Straw and Ball remained with 30,000 followers. The next morning the massacre continued. P106 The King went to church and then sent a message for all rebels to meet at Smithfield. They were led by Wat Tyler. The King asked the Mayor of London, William Walworth, to summon Tyler. Tyler was shockingly over-familiar with the King. He approached on a small horse so that he might be seen. He dismounted but held a small dagger in his hand, he half bent his knee and then took the King by the hand and shook it roughly saying “Brother, be of good comfort and joyful, for you shall have, in the fortnight that is to come, praise from the commons even more than you have yet had, and we shall be good companions.” P110 The King asked them to leave and Tyler demanded his charter and the King promised him what he wanted. Tyler sent for a flagon of water and washed his mouth out in a rude and disgusting manner. Then he demanded a jug of ale and drank deeply. Then he remounted his horse. Then a man of the King’s from Kent recognised Tyler and called out that he was “…the greatest thief and robber in Kent..” Tyler tried to attack him with his knife, in the King’s presence. The Mayor arrested him but Tyler stabbed him (luckily he was wearing armour under his robes). Then the Mayor struck Tyler with his sword on his neck and head and another of the King’s men drew his sword and ran Tyler though. As he was dying he called for the commons to avenge him then he fell from his horse. P111 The King was in great danger because many of Tyler’s followers were archers and they cried out, “They have cut down our captain.” The king rode up to them and said “Gentlemen, what do you want? You have no captain but me. I am your King. Keep the peace.” Some of the crowd then began to disperse. The King left the 8 rest out to Clerkenwell Fields where they were surrounded by citizens and guards summoned by the Mayor. Meanwhile the Mayor went to look for Tyler at Smithfield and was surprised to find the body gone. He had been taken to a local hospital. The Mayor had him taken to the middle of Smithfield and beheaded. With the death of Tyler the revolt in London collapsed. Many fell to the ground before the King and pleaded for mercy for their misdeeds. Mercy was granted and the hurried off home. Chapter Twelve: The End of the Revolt P113 While this had been happening in London there had been serious rioting around the countryside. The Bishop of Norwich rounded up rebels and heard their confessions and executed them. The King sent out an order to capture rebels and many were rounded up and executed. P114 Most of the ringleaders were rounded up and executed. John Ball did not deny the evidence against him and was hanged in the King’s presence on the 15th July 1381. William Grindcobbe led the rising at St Albans and was arrested and released on the condition that he subdued his followers. Instead he declared to them: :Friends, who after so long an age of oppression, have at last won yourselves a short breath of freedom, hold firm while you can, and have no thought for me and what I may suffer. For if I die for the cause of liberty that we have won, I shall think myself happy to end my life as a martyr. Act now as you would have acted supposing that I had been beheaded at Hertford yesterday.” He was taken back to prison and executed. On the whole the government acted with moderation. Executions were later followed by pardons. The royal charters were “recalled and annulled” P116 But it was impossible to set the clock back. The issues remained and sporadic risings took place. The revolt had failed but serfdom was already declining. Landlords found it more profitable to release serfs and hire labour. 9