Market structure and price determination of foodgrains in Bangladesh

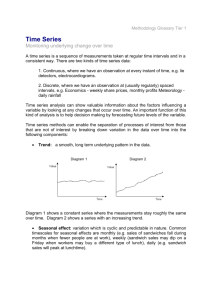

advertisement