Full paper - University of South Australia

advertisement

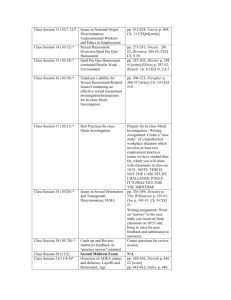

Using the CEQ as an impetus for improving learning and teaching: A whole-of-school approach Beverley Oliver, Curtin University of Technology, b.oliver@curtin.edu.au Shelley Yeo, Curtin University of Technology, s.yeo@curtin.edu.au Abstract: This paper discusses a program designed to initiate change in learning and teaching within whole schools or departments. Data generated by student evaluation of teaching instruments, such as the CEQ, are analysed and presented in compelling, easy to interpret format. Through this, schoolwide strengths and weaknesses in student learning are identified. After presentation of the findings to a school, teaching staff identify strategies for bringing about change within the school. Using CEQ data as the impetus for improvement in teaching and learning is not new and there are mixed reports about its effectiveness, particularly if the aim is simply to improve scores. The deeper aims of this program are to bring about the type of cultural change needed to transform teaching practice through guided collegial discussion on learning and teaching issues and scholarship. Keywords: CEQ, student evaluation of teaching, higher education Introduction This paper reports on a project aimed at improving learning and teaching at Curtin University of Technology. It is a joint project of the Learning Support Network (LSN) and University Planning (UP). The process aims to provide academic departments with analysis of data from instruments such as the Course Experience Questionnaire (CEQ) and the Curtin Assessment of Student Satisfaction (CASS), to help teaching staff to understand the links between educational practices and student evaluations of teaching, and to subsequently develop – as a school or department – ways of improving students’ learning experiences and outcomes. Curtin University of Technology is divided into five main divisions, with the divisions subdivided into discipline-based schools (and in some cases, departments). Academic staff typically value the research basis of their own discipline but sometimes lack awareness of the research basis of their concurrent academic role, teaching. It can be difficult to engage staff in scholarly debate about teaching and learning because few are either familiar with the literature of research on higher education or know about their own disciplinary education research literature. In some cases, even those with an education background have not managed to keep abreast with changes in education theory or practice. While the ideal would be for every teaching academic and school to participate in staff development programmes to keep them abreast of the latest ideas in effective teaching practice in their discipline, such programmes are beyond the temporal and financial constraints of most universities. This project recognises those constraints, and so aims to present teaching staff with (i) sound and compelling reasons, supported by data from student feedback, for the need to change teaching and learning practices; and (ii) a set of relevant strategies that make educational sense, that are aimed at improving the data, and which are feasible given the constraints and circumstances of staff and schools. Quality of learning and teaching Data from the CEQ and CASS provide evidence of students’ perceptions of the quality of learning and teaching within a school. The CEQ, which measures some aspects of the quality of learning and teaching and the development of generic skills (Wilson, Lizzio & Ramsden 1996), is used to survey all graduates from all Australian universities soon after graduation. It is considered a useful instrument for the purpose of improving the quality of teaching in universities and also for informing student choice, managing institutional performance and promoting accountability of the higher education sector (McInnis et al. 2001). This information base is funded by the Federal Department of Education, Science and Training (DEST) and supported by the Australian Vice-Chancellors’ Committee (AVCC). CEQ data are derived from graduates and are usually not available until about a year after those graduates have left the University. CEQ scores provide the opportunity to benchmark the quality of learning and teaching both nationally and within the local university. The CASS is an internal Curtin online evaluation instrument available to the whole student body in September each year. Its purpose is to collect data on students’ perceptions of all areas of campus life, including learning and teaching, learning spaces, library facilities and the availability of computers. Some items relating to teaching and learning are very similar to CEQ items. For example: The teaching staff in my course motivate me to do my best work. The teaching staff give me helpful feedback on how I am going. The goals and requirements of my course are made clear to me. The items have a five-point response scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Unlike the CEQ, items are not aggregated into scales. CASS scores are an important intrauniversity student evaluation of the quality of learning and teaching, and the data from this instrument have the added advantage of being available to the Curtin community a short time after the instrument is used. The Project Our project involves benchmarking a school’s CEQ scores against divisional and university data and national equivalent Field of Study CEQ scores. CASS data adds to the richness and currency of information derived from students. It provides data from students in all years, which is useful because CEQ data is from graduates and is not available until about one year after they have graduated. We present the data and a brief analysis in a report to schools, and subsequently work with school staff to evaluate their data and teaching practices, and find solutions for identified problems. Provision of CEQ data to universities, divisions or schools for the purpose of improving teaching and learning is not new (Wilson, Lizzio & Ramsden 1996; Trembath 1999; Niland 1999). However, there is some evidence that staff do not know what to do with the data or how to respond to it effectively. As Patrick (2003) notes, the intent of the CEQ is not always clear to staff and that the CEQ alone cannot provide them with the information that they need to make actual improvements in students’ experiences. We also take the view that simply reporting data or results summaries to schools with little or no follow-up and support will result in no substantive change at the teacher or classroom level. Students may report excessively high workloads or assessment that emphasises rote learning but if staff do not connect these perceptions with their own teaching behaviours no change will happen. Hence, it is not surprising that schools and universities do not see improvements in CEQ scores even after being provided with appropriate data. Thus, a core element of this project is to help staff understand the research origins of the CEQ and to value the data for the information that it provides. We ‘unpack’ the instrument scales to make more explicit the links between what staff do (or might do) in classrooms and how this affects students’ learning behaviours and their perceptions of teaching. So far, sixteen schools in four divisions have become part of the CEQ improvement programme. This is greater than we had anticipated for the first year of the programme. The scales most commonly identified as needing improvement are Good Teaching, Appropriate Workload and Appropriate Assessment. Reports When schools volunteer to become part of the programme, their CEQ data are collected, analysed and presented back to the school as a report. The CEQ data is primarily in graphical form. The first graph for each scale compares the school’s performance with that of the relevant division and the University as a whole for a period of five years (1998-2002). See Figure 1. The second graph compares the school’s data with national data over the same five years. School data is compared with the mean of the three highest-scoring and the three lowest-scoring schools nationally in the same field of education/study. See Figure 2. The scale in the graphs (–100 to +100) is proportional to the item scale, 1 to 5, where the middle scale score of three corresponds to zero on the graphs. This is the neutral point where students neither agree nor disagree with each statement. A score of less than zero on the graphs corresponds to an overall negative response for the scale. In addition, a brief statistical analysis of the school’s teaching-related data from CASS is provided where available, and where there are sufficient data for inferences to be made. The report also contains sufficient guidance to enable staff to evaluate the data for themselves. Good Teaching Scale - University Comparisons 100.0 75.0 50.0 25.0 0.0 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 -25.0 -50.0 -75.0 -100.0 School. Division Curtin Figure 1. Graph showing comparison between school, division and university CEQ data over a five-year period (1998-2002). Good Teaching Scale - National Comparisons 100.0 75.0 50.0 25.0 0.0 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 -25.0 -50.0 -75.0 -100.0 School. Mean Top 3 Aust. Uni/s Mean Bottom 3 Aust. Uni/s Figure 2. Graph showing comparison between school CEQ data and mean of the three highest and three lowest scoring universities’ CEQ data for comparable courses/fields of study over a five-year period (1998-2002). Taking reports to schools The graph that generates most productive discussion with staff is the one displaying national data (based on the CEQ). It is the one about which most concerns are raised but paradoxically, the one that leads to better discussion outcomes. When staff are presented with the CEQ data, their first responses are often to question the data, the sample sizes and to bemoan the lack of resources or high workloads in comparison with better resourced universities. Once these issues have been worked through (and there are cogent arguments for doing this) and staff encouraged to find meaning in the data and implications for their courses and themselves as teachers, they will finally address real teaching and learning issues. When staff eventually ask such questions as: Why do the students at other universities perceive the teaching and learning in Course X to be better (or worse) than do students at Curtin? Is the teaching different? Why are students saying that assessment is less ‘appropriate’ at our university compared with another?, they really begin to address fundamental issues in teaching and learning. They then start to engage productively in talk about perceived shortcomings, targets they should aim for, what can be realistically achieved and so on. The national data graphs seem to indicate what is possible and achievable. Unpacking the scales We believe that it is important for staff to understand what each CEQ scale measures. To begin with, the titles given to scales can be misleading. The ‘Appropriate Assessment’ scale is really about inappropriate assessment insofar as it refers to the extent to which students perceive that their assessment rewards rote learning of facts. It is not about assessment task clarity, relevance or variation, links to learning outcomes, fairness, quality of the assessment process or amount of assessment – all of which might be indicators of ‘appropriate assessment’. In a similar way, the Appropriate Workload scale might also be considered to measure inappropriate workload. It talks about ‘pressure to do well’ and ‘sheer volume of work’. It is also very difficult to know what students make of these terms – pressure from whom, number or length of readings, class contact hours, assessment tasks etc. The most widely used form of the CEQ consists of five scales of between three and six items and one item asking students’ to rate their overall satisfaction with their course. The five scales are called: Good Teaching, Clear Goals and Standards, Appropriate Workload, Appropriate Assessment and Generic Skills Research underpinning the design of the CEQ suggests that the instrument does not measure ‘good teaching’ but rather it is a “… proxy measure for the quantity and quality of student learning outcomes ...” (Ramsden 1999). It thus measures how students experience aspects of the learning environment that affect how they go about their learning. More exactly, it measures the extent to which students perceive they have been involved in ‘good learning’ practices. This last point is not well understood by many academic staff. ‘Unpacking’ a CEQ scale involves identifying the ‘effective’ learning behaviours implicit in the scale construction, or teaching strategies or models that support these behaviours. For example, the items in the Clear Goals and Standards scale are: It was always easy to know the standard of work expected I usually had a clear idea of where I was going and what was expected of me in this course It was often hard to discover what was expected of me in this course The staff made it clear right from the start what they expected from students We have identified the underlying educational factors in this scale as: Formulating and communicating clear learning outcomes Mapping assessments to learning outcomes Developing explicit grading criteria for assessment tasks Hence, we focus discussion not on the scale items but on the important educational factors that give students the learning experiences on which they base their responses to items in questionnaires. Strategies for improvement We consider improvement strategies under two headings – Classroom strategies and School strategies. Each is designed to help staff individually and collectively to reassess their own practices and to conceptualise how they might adopt better, more effective teaching behaviours. During follow-up sessions, staff are encouraged to identify weaknesses and to devise their own strategies in response to what they perceive as the needs of themselves and their students. We also provide a limited list of strategies (drawn from a large set) for any given school depending on our perception of their needs. ‘Classroom strategies’ for improving the Clear Goals and Standards scale include such suggestions as: List the learning outcomes of your unit (subject) clearly and prominently on the Unit Outline, then show how each outcome is tested in the assessment for the unit. Give students models of excellent, acceptable and unacceptable practices or pieces of work for them to critique or to emulate. Take time each week to remind students where they are in the programme, what is coming up and what they need to have completed. A school-based strategy would be: Ensure all unit outlines have clearly stated student learning outcomes. How do staff respond to the need for change? Implementing change in the context of learning and teaching is an involved process (James, McInnis & Devlin 2002). We have found that, initially, many staff do not have an immediate solution other than to try to ‘do the same better’. They do not have the epistemological or pedagogical resources to conceptualise a fundamental change in their teaching behaviours or to believe that some of the suggested strategies can possibly result in improved learning. It has been noted that staff who traditionally adopt a strongly ‘teacher-focused’ approach appear to have most difficulty believing that there are effective alternatives (Trigwell & Prosser 1996). Thus staff subconsciously (or otherwise) reject many strategies as being unreasonable, potentially ineffective or simply nonsense. Thus to have staff change their practice is not easy. For some (and arguably more in science and engineering disciplines) changes in teaching behaviour requires a type ‘cultural change’ to occur in either the individual and/or within the school (Patrick 2003). We describe our experiences in further implementing this approach with staff in the Division of Engineering, Science and Computing in more detail in another paper to be delivered at this conference. See Gribble, Yeo and Zadnik. Resolving problems and issues There are a number of problems and issues to be resolved in getting this project up and working: In relation to CEQ data, there may not be easily recognised ‘equivalent’ Fields of Study (or education) for national data comparison. Does ‘Public Health’ at Curtin equate to ‘Public Health’ elsewhere? Where there has been uncertainty, it has been necessary to look at elements of the programme or course structure at different institutions. What is the ‘significance’ of data differences and trends? This is one of the first questions asked by many staff. In our reports to the schools, we have attempted to address concerns about the meaningfulness of data without imposing undue complexity on data presentation. We argue that one should not focus unduly on any individual data point but consider trends or broad comparisons in relation to expectations. We have chosen to use the school as the unit of analysis – even if there are two or three courses taught within the school. Smaller numbers (as for course-level analysis) result in more variation and uncertainty in the data. Aggregating course data for a given school results in larger numbers but may provide less interpretable data and has lead to staff concerns that their course’s results are confounded by those of the other course(s). Getting schools to take part in the project is sometimes difficult. There are several impediments to school involvement – time, willingness, satisfaction with existing CEQ data etc. On this last point, some divisions or schools always have better scores than the rest of the University, leading staff to believe that they do not need intervention or change. There seems little doubt that the CEQ favours the dominant teaching culture in some disciplines (and is at odds with others) but we argue that comparisons between different disciplines is not a valid use of CEQ data – even within the one university. Staff in a school that has always had ‘good’ CEQ scores may be surprised to learn that these are only average or below when compared with data from equivalent schools elsewhere in Australia. This alone may prompt the request for more information. Staff all have similar concerns and questions about the CEQ data that must be addressed. For example, there is a tendency to argue that there is a difference between the population of students who responded to the surveys and the population that did not respond. If presented with relevant research data to counter such arguments (e.g. Guthrie & Johnston 1997), staff usually ‘take this on board’ and are prepared to move on. In addition, more immediate data generated by CASS helps to allay staff concerns that respondents to the CEQ have already left the university system Conclusion The aim of this programme has been to take measures of some importance to teachers and schools – even imperfect measures of students’ perceptions such as CEQ and CASS – and to present an analysis of the data which highlights a schools’ strengths and its weaknesses. This “whole school approach” has several important benefits, among them is the opportunity for colleagues to discuss whole of school as well as classroom strategies for improving student learning. While students’ perceptions of teaching are only one aspect of teacher and course evaluation, they do provide an impetus for commendation – where teaching practices are effective – and recommendation – where teaching practices are seen as ineffective. This project aims to ‘kick start’ the conversation among colleagues about how to improve learning. Acknowledgements We gratefully acknowledge Matthew Griggspall and Julie-Ann Pegden for their work in preparing the school statistical reports for this project. References Guthrie, B. & Johnston, T. 1997, Study of non-response to the 1996 Graduate Destination Survey, DEETYA (AGPS), Canberra. James, R., McInnis, C. & Devlin, M. 2002, Assessing learning in Australian universities: Ideas, strategies and resources for quality in student assessment, Centre for the Study of Higher Education, Melbourne. McInnis, C., Griffin, P., James, R. & Coates, H. 2001, Development of the Course Experience Questionnaire (CEQ), Centre for the Study of Higher Education, Melbourne. Niland, J. 1999, 'The CEQ and accountability: a system-wide perspective and the UNSW approach', in T. Hand & K. Trembath, (eds.), Course Experience Questionnaire Symposium, 1998, DETYA, Sydney (The University of New South Wales), pp. 5-15. Patrick, K. 2003, 'The CEQ in practice: Using the CEQ for improvement', in GCCA symposium: Graduates, Outcomes, Quality and the Future, Canberra, March 2003. Ramsden, P. 1999, 'The CEQ looking back and forward', in Course Experience Questionnaire Symposium 1998, eds. T. Hand & K. Trembath, DETYA, Sydney (The University of New South Wales). Trembath, K. 1999, 'Enhancing and customising the analysis of the CEQ', in T. Hand & K. Trembath, (eds.), Course Experience Questionnaire Symposium, 1998, DETYA, Sydney (University of New South Wales), pp. 93-116. Trigwell, K. & Prosser, M. 1996, 'Changing approaches to teaching: A relational perspective', Studies in Higher Education, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 275-284. Wilson, K. L., Lizzio, A. & Ramsden, P. 1996, The use and validation of the Course Experience Questionnaire, Griffith Institute for Higher Education, Nathan, QLD. This paper was first presented at the Evaluations and Assessment – a Commitment to Quality Conference, Adelaide, November 2003.