human rights and international relations

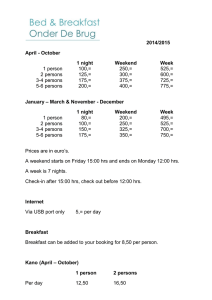

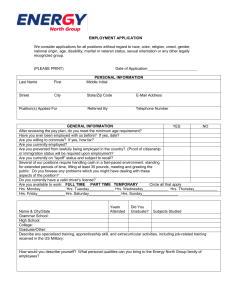

advertisement