NationalPatentJuryInstructions

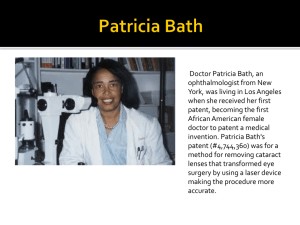

advertisement