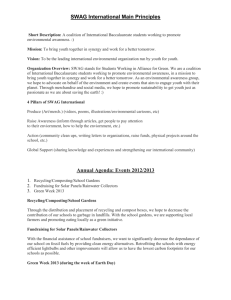

The Origins of the International Socialists

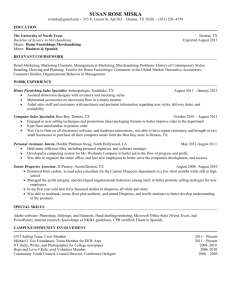

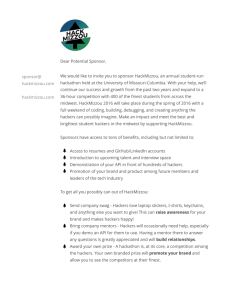

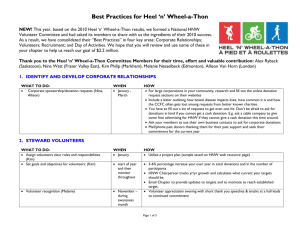

advertisement