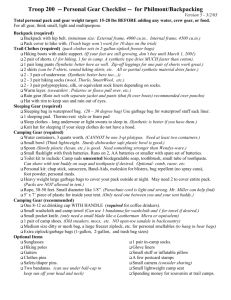

Backpacking 101 from Backpacker magazine

advertisement