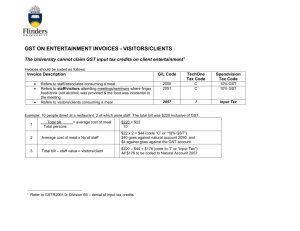

GST And Imported Services - Tax Policy website

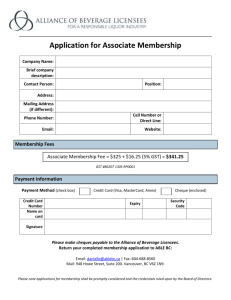

advertisement