UWA_UnitOutline - The University of Western Australia

advertisement

Evidence – Laws 3310

Semester 2, 2007

Unit Outline

All material reproduced herein has been copied in accordance with and pursuant to a

statutory licence administered by Copyright Agency Limited (CAL), granted to the

University of Western Australia pursuant to Part VB of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

Copying of this material by students, except for fair dealing purposes under the Copyright

Act, is prohibited. For the purposes of this fair dealing exception, students should be

aware that the rule allowing copying, for fair dealing purposes, of 10% of the work, or

one chapter/article, applies to the original work from which the excerpt in this course

material was taken, and not to the course material itself.

© The University of Western Australia 2006

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

Important Notice to Students

Please note this study guide is supplementary to the course

lectures and tutorials.

Information provided in this study guide is subject to change

throughout the semester.

Students should not rely on the contents of this study guide as a

substitute for lectures and/or tutorials.

Unit Outline

Introduction

Welcome to LAWS 3310 – Evidence. For many of us, courtroom scenes on television or

in the movies were our first introduction to the law in operation. Although it all looks

rather dramatic, we do need to be careful. Television and film producers are permitted

something that lawyers, generally, are not – artistic licence! Also, as you have probably

guessed, the US produced programs can be rather misleading as their advocates are

permitted to be far more flamboyant than those in Australia.

However, through your television and movie viewing (probably when you should have

been studying but we will not dwell on this); you will find you will already be familiar

with some of the terminology used in the courts. For example you will have heard of

Examination in Chief and Cross Examination. You will have heard references to Hearsay

and a prohibition on ‘leading’ the witness. Perhaps you have heard of the need for

corroboration in certain types of case. Also, when listening to or reading reports of highprofile cases in the media, you may have questioned why juries are (usually) not made

aware of the previous convictions of an accused or why certain witnesses may be excused

from testifying through a claim of privilege. Hopefully, over the next 13 weeks, all will

be revealed!

The subject will provide students with a basic understanding of the common law and the

main pieces of legislation dealing with the law of evidence. The emphasis will be on the

common law and the Evidence Act 1906 (WA). Other legislation will also be examined

where applicable. Although reference will be made at times to the Evidence Act 1995

(Cth) this legislation will not be examinable. The emphasis in the course will be on the

practical application of the law, however, an understanding of theories relevant particular

areas of the law of Evidence will be referred to at times.

In your other law subjects to date, you have generally looked at the elements of an

offence or a cause of action. For example, in Criminal Law, you would have considered

whether the elements of the relevant provision of the Criminal Code have been satisfied.

The elements may seem to be satisfied on the facts in your problem but in Evidence we

go one step further. In this subject we will be looking at, for example, what evidence the

Prosecution must present to establish that the accused person has committed the offence.

What is the standard of proof required? In a criminal matter it is, of course, beyond

reasonable doubt.

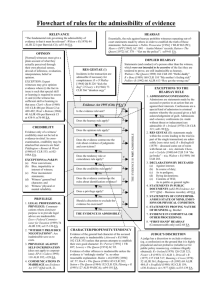

We will look at the types of Evidence, for example, real evidence, documentary evidence

and oral testimony. We also examine the rules of Evidence which dictate whether or not

the evidence sought to be presented to the court is admissible.

Now, just a word of warning. Evidence is tricky. It is a large subject. There is a lot of

information to take in. At times you will feel a little over-whelmed. It is one of those

subjects that can be compared to a large jigsaw puzzle. All through the semester we will

try to put the pieces together and it may not feel as though you are getting the full picture.

However, suddenly (hopefully) at the end of the semester everything should fall into

place. On the brighter side, Evidence is really very interesting, topical and, dare I say,

quite an exciting subject.

1

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

Assessment

Component

Weight

Due date

Mid-term assignment

30%

Students will receive the assignment

(via internet and hard copies available

at the Law School Reception) on

Friday 17 August at 12.00pm. The

assignment should be submitted by

12.00pm on Friday 24 August.

Final exam

70%

As scheduled

Tutorial exercises/activities

In 2007, tutorial participation in Evidence is not assessable. However, regular attendance

is highly recommended.

Assignment

The assignment will be worth 30% of the marks in this subject. It will be in the form of a

problem question based on material from weeks 1-4 of the course. The assignment will be

distributed at the end of week 4. It will available on the internet and at the Law School

Reception from 12.00 pm on Friday 17 August at 12.00pm. The assignment should be

submitted by 12.00pm on Friday 24 August. The assignment will be 2000 words in length

(maximum). There will be no lectures or tutorials in week 5 so you can focus on your

assignment. The material on the assignment will NOT be re-examined on the end of

semester examination.

Final exam

Due to the broad nature of the subject and the number of issues canvassed the coordinator

believes this is the most appropriate way to ensure students cover the majority of issues in

the course. The examination will be scheduled in the November examination period. The

examination will consist of a choice of questions on material from weeks 6-13. The

questions will be primarily problems but some may contain a short essay or a short

answer question. The examination will be worth 70% of the total marks for the subject.

More information will be provided during the semester.

The Evidence team in second semester 2007 is made up of Eileen Webb, Christian Porter,

Penelope Giles, Anthony Papamatheos, Laura Timpano and Judith Seif. We hope you

enjoy the lectures and tutorials. If you have any questions throughout the semester, please

do not hesitate to contact us – we are here to assist.

Goals

Evidence is a large subject and it is impossible to cover everything in a 13 week course.

Therefore our goal is to provide an overview of evidence law pursuant to the common

law and Evidence Act 1906 (WA). The subject aims to provide an introduction to the

fundamental rules of Evidence and to assist students in understanding and applying these

rules when utilised in the course of a civil or criminal matter.

2

Unit Outline

Broad learning outcomes

On completion of this unit, students will:

Appreciate the role played by the rules of evidence in litigation;

Identify the major case authorities relevant to each area of the law of evidence

studied, and discuss the relevance of those cases to the Evidence course;

Identify evidence needed to prove a client's case or disprove an opponent's case,

according to the rules of evidence;

Have acquired a good working knowledge of the most important rules of

evidence and an ability to apply those rules to diverse factual scenarios;

Understand the main sources, principles, techniques, terminology and concepts of

the law of evidence in Western Australia;

Developed skills in the analysis of evidence.

Contact details

Unit web site URL

Unit coordinator

Name:

e-mail:

Eileen Webb

ewebb@law.uwa.edu.au

phone:

6488 2947

fax :

6488 1045

Consultation hours :

TBA

Unit coordinator

Name:

Christian Porter

e-mail:

christian.porter@uwa.edu.au

phone:

6488 1754

fax :

6488 1045

Consultation hours :

Monday and Thursday 9.30am to 10.00am

Prerequisites

This unit assumes that students have already developed certain basic skills. It is expected

that students have an adequate command of:

1.

English and related communication skills – students are expected to have very high

English language skills and to be able to understand and follow the principles of

accepted expression and style;

3

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

Library research skills – research is an important aspect of studying law and

students will be expected to utilise the facilities of the Law Library on a regular

basis.

2.

If you are not well prepared in any of the above areas you should make every effort to

remedy the situation through undertaking additional reading and/or practice. Do not

hesitate to ask for advice from your tutor.

The University’s Student Learning, Research and Language Skills Service offers

assistance in a variety of areas, including writing skills, study skills, examination

preparation skills and stress management. The service is located on the second floor of

the Guild Village, south entrance/ exit and can be contacted by telephoning 6488 2423 or

6488 2258.

Unit-specific prerequisites

200-130 The Legal Process

It is highly recommended that students should have completed Criminal Law 1 &

2 before undertaking the Evidence course.

Lectures

Monday

1.00 -1.45 Wilsmore lecture theatre, Chemistry Building.

Monday

2.00 -2.45 Wilsmore lecture theatre, Chemistry Building.

Wednesday

3.00 -3.45 Wilsmore Lecture Theatre, Chemistry Building

Attendance at lectures is not compulsory but is highly recommended. All lectures will be

recorded and will be available on the internet.

Tutorials

Tutorials will be held once per fortnight. Students will be allocated according to their

preferences indicated on the online class registration system.

4

Unit Outline

Unit schedule

Week

Topic

Lecturer

Tutorials

Administrative matters

1

23 July

Introduction to the law of

Evidence

Christian Porter

Relevance and

admissibility

2

30 July

3

6 Aug

4

13 Aug

The Course of the Trial

Competence and

compellability

Christian Porter

Christian Porter

Tutorial Groups

1-8

The accused as a witness

Question 1

Identification evidence

Tutorial Groups

9-16

Christian Porter

Question 1

5

20 Aug

6

27 Aug

Lecture free week due

to assignment

preparation

Opinion evidence

Christian Porter

Tutorial Groups

1-8

Question 2

7

3 Sept

Confessions and

admissions

Christian Porter

Tutorial groups

9-16

Question 2

Mid-Semester break

8

17 Sept

Tutorial Groups

1-8

Disposition and character

Eileen Webb

Similar fact evidence

Question 3

5

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

9

24 Sept

Hearsay

Eileen Webb

Tutorial Groups

9-16

Question 3

10

1 Oct

11

8 Oct

12

15 Oct

Exceptions to Hearsay

Eileen Webb

Res Gestae

Tutorial Groups

1-8

Question 4

Privilege

Eileen Webb

Corroboration

Real Evidence

Documentary Evidence

Tutorial Groups

9-16

Question 4

Eileen Webb

Tutorial Groups

1-8

Question 5

13

Revision

Eileen Webb

22 Oct

Tutorial Groups

9-16

Question 5

Textbook(s)

Recommended/required text(s)

Evidence Act 1906.(WA)

Arenson and Bagaric, Rules of Evidence in Australia, 2005, Butterworths, Australia

(“Arenson and Bagaric”) OR

P.K. Waight and C.R. Williams, Evidence - Commentary and Materials (6th

Edition), c.2002, LBC Information Services, Australia (“Waight and Williams”)

Additional/Suggested/Alternate text(s)

S.B McNicol, D.Mortimer, Butterworths Tutorial Series – Evidence (3ndEdition) c.2005,

Butterworths Ltd, Australia

The Hon. Justice Heydon, Cross on Evidence (7th Australian Edition), c2004, LexisNexus

Ltd., Australia

A Ligertwood, Australian Evidence (4th Edition), 2004 Lexis Nexis Butterworths

6

Unit Outline

Unit web site

TBA

Policies

The information in this unit outline has been prepared to answer the questions most

commonly asked by students enrolled in this unit. In addition to matters relating

specifically to this unit (eg class attendance), it summarises some of the information

contained in the Faculty of Law Handbook (and the abbreviated First Year Handbook)

and other Faculty of Law Policies.

This unit does not provide a comprehensive statement of Faculty of Law policy.

You should refer to those documents for any further information you require.

The Law School Policies you are most likely to want to refer to are:

Faculty of Law Examination Rules and Guidelines

Faculty of Law Credit Policy

Faculty of Law Cross-Institutional Enrolment Policy

Copies are available on the Law School website – Student Information Link - or by

emailing lawgen@law.uwa.edu.au.

The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Law School provides the Law School's policies in relation

to a number of matters

You will find an electronic copy of this guide and other useful administrative information

in the ‘Handbook’ section of the Law School home page: http://www.law.uwa.edu.au/.

Copies are also available in the Law Library for reference.

Class attendance

Attendance at and participation in all classes is always helpful to your learning. The role

of regular attendance and participation in calculating your assessment will depend on

your teacher. Your teacher will provide you with a copy of his or her policy on the matter

in the first class.

It is important you select the appropriate class time because once the lecture, tutorial and

small group allocation lists are finalised you will be permitted to change classes only in

exceptional circumstances. A student exit note will need to be completed. These are

available from Law School Reception. This process requires approval from the class

teacher of the class you are leaving and the class you wish to attend. The signed form will

need to be returned to Law School Reception. It is necessary to use this system because

for classes to be effective maximum numbers need to be set and switching classes after

allocation is very disruptive.

Submission of assignments

The following guidelines on submission of assignments have been extracted from the

‘Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Law School’.

7

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

Assignments should be submitted with a cover sheet which is available from the General

Office and contains the following information:

(a) Unit title.

(b) Student number - not student name.

(c) Lecturer's name.

(d) Lecture time and day.

(e) A declaration of the number of words.

Assignments should be typed where possible. Students are also required to retain a copy

of their assignment to safeguard against the possibility of loss or theft.

Assignment extensions

If a student is unable, for valid reasons, to comply with the deadlines for submission of an

assignment he or she may seek an extension of time from the unit co-ordinator prior to

the submission day. Students should contact the unit co-ordinator to discuss their

difficulties as soon as possible.

Applications for an extension of time should be in writing and should be supported by

medical certificates where appropriate.

Work conflicts and other educational

commitments will not ordinarily be considered sufficient to warrant an extension.

Late submission of assignments

Assignments must be handed in on time. The time for handing in assignments will be 12

noon on the due day at the Law School General Office unless otherwise advised. If a

student submits an assignment after the normal or extended date without approval, he or

she will be penalised by a loss of marks. The reason for this is simply to ensure fairness to

other students who hand in their assignments on time.

The penalty that will be incurred for all first year units is a proportional deduction of 5%

of the marks per day.

Exceeding word limits on assignments

Assignments must be within the stated word limit. The main reason for this is to

encourage students to write in a clear, concise and efficient manner. If a student submits

an assignment that exceeds the word limit, he or she may be penalised by a loss of marks.

Once again, as with late submission of assignments, the reason for imposing a penalty for

excessive words is to ensure fairness to other students who have complied with the word

limit.

The number of words in an assignment includes all the words in the text including

definite and indefinite articles, real nouns, headings and quotations. Footnotes are not

included in the word count provided they are used only to give citations or other brief

information. If footnotes are used more extensively to provide commentary then these

additional words may be counted.

The marks will be reduced by the percentage by which the word limit was exceeded.

Students are required to make a declaration of the number of words used in their

assignment. A misstatement of the number of words may be considered by the University

as academic dishonesty amounting to student misconduct.

8

Unit Outline

Use of non-discriminatory language

The University of Western Australia Senate has affirmed support for the principle of nondiscriminatory language. Teachers in this unit are committed to the use of nondiscriminatory language in all forms of communication. Both students and staff should

avoid the use of discriminatory language in this unit. This applies to both oral and written

communication.

Discriminatory language is that which excludes or refers in abusive terms to those of a

particular gender, race, age, sexual orientation, citizenship or nationality, ethnic or

language background, physical or mental ability, or political or religious views, or which

stereotypes groups of people. This is not meant to preclude or inhibit legitimate academic

debate on any issue; rather it is a means of opening debate to all without the pressures of

the risk of ridicule.

Guidelines on avoiding discriminatory language can be found in Non-Discriminatory

Language: A guide for staff and students prepared by the Equal Opportunity Advisory

Committee. This pamphlet is available from the Equity Office, or on the WWW at:

http://www.acs.uwa.edu.au/hrs/policy/part04/6.htm.

For further guidelines on ways to avoid written discriminatory language, please see Style

Manual for Authors Editors and Printers (Canberra: AGPS) 6th ed

Academic dishonesty

All forms of cheating, plagiarism and copying are condemned by the University as

unacceptable behaviour. The Faculty’s policy is to ensure that no student profits from

such behaviour. The following is a summary of the Law School’s policy on plagiarism

and collusion.

Plagiarism occurs when a person takes the words or ideas of another and presents them

as his or her own, without acknowledging the original source.

Collusion is where two or more students work together and submit the same or similar

work for assessment as if it were the independent work of the student submitting it.

Deliberate plagiarism and collusion are forms of academic fraud and as such are viewed

as serious misconduct by the Law School and the University. Even unintentional

plagiarism is unacceptable, because it results from sloppy scholarship and falls below the

standards of attribution expected in academic work.

A full statement of the Law School's policy on plagiarism and collusion, including advice

to students on how to avoid infringing the policy, is available from the Law School home

page and the Business Law home page.

All written work submitted for assessment must carry a declaration by the student that the

work complies with the policy, and an acknowledgement that the assignment may be

electronically examined for evidence of plagiarism or collusion.

All suspected cases of deliberate plagiarism or collusion will be investigated by a

committee appointed by the Dean. Penalties for plagiarism or collusion include the loss of

marks, fines, and suspension.

Supplementary and deferred examinations

Supplementary Examinations

9

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

Students who fail a unit will only be permitted to sit a supplementary examination if they

fall into one of the following categories:

(i)

A student who receives a final mark of between 45 and 49 per cent in Legal

Process, Contract 1, Criminal Law 1, Torts 1, Property 1or Administrative Law 1 will be

awarded automatic supplementary assessment in the unit.

(ii)

A student who receives a final mark of between 45 and 49 per cent in Contract 2,

Criminal Law 2, Torts 2, or Property 2 will be awarded automatic supplementary

assessment in the unit provided that the student is in the second semester of their Law

studies.

(iii)

A student who is in the final semester of their LLB degree and who receives a

final mark of between 45 and 49 percent in a unit will be awarded automatic

supplementary assessment provided that the unit in question is the one remaining unit

required to complete the LLB degree.

(iv)

A student who receives a final mark of between 45 and 49 per cent in a unit

where the only form of assessment available is an examination (other than a “take-home”

examination) will be awarded automatic supplementary assessment in the unit.

Students re-examined by supplementary examination are classified pass or fail.

Enquiries concerning entitlement to, and scheduling of, supplementary examinations

should be directed to the Associate Dean.

The supplementary examination will be on all material covered in the unit (ie material

covered in Semesters 1 and 2 in the case of a year long unit).

Deferred examinations

A student may be permitted to take a deferred examination in one or more units if the

Dean of the Faculty is satisfied that for medical or other exceptional reasons the candidate

was either (a) substantially hindered in preparation for an examination; or

(b) absent from or unable to complete an examination.

Students wishing to apply for a deferred examination must complete the necessary

application form and hand the application form and any attachments to the Associate

Dean. The latest date such an application can be submitted is three University working

days after the date of the relevant scheduled examination.

Requests for special consideration

The Board of Examiners may give special consideration to medical or other exceptional

and unavoidable factors which may have substantially hindered the student's preparation

for or performance in an examination in cases where the student was still actually able to

sit the scheduled examination and could not be available for or benefit from taking a

deferred examination.

There is no discretion to award further supplementary assessment outside of those

conditions listed above. Students in the Faculty of Law who apply for special

consideration will, in appropriate cases, be awarded deferred examinations. Applications

should be made to the Associate Dean before the examination period, or where that was

not possible within 3 working days of the examination.

10

Unit Outline

Appeals against academic assessment

If students are unhappy with their mark for assessable work in a Law School unit, they

should, in the first instance, speak to the Unit Coordinator.

If students feel they have been unfairly assessed, they have the right to appeal their mark

by submitting an Appeal against Academic Assessment form to the Head of School and

Faculty Office. The form must be submitted within twelve working days of the formal

despatch of your unit assessment.

It is recommended that students contact the Guild Education Officers to aid them in the

appeals process. They can be contacted on +61 8 6488 2295 or

education@guild.uwa.edu.au. Full regulations governing appeals procedures are available

in the University Handbook, available online at

http://www.publishing.uwa.edu.au/handbooks/interfaculty/PFAAAA.html .

Information and advice on the appeal procedure and a booklet entitled Appeals against

Academic Assessment is available from the Associate Dean, Faculty Administrative

Officer and the Student Guild.

Students who have been awarded a fail grade and who are contemplating an appeal

should be aware that in the Law School, as a matter of course, all fail scripts are required

to be second-marked before the publication of results.

Charter of student rights

This Charter of Student Rights upholds the fundamental rights of students who undertake

their education at the University of Western Australia.

It recognises that excellence in teaching and learning requires students to be active

participants in their educational experience. It upholds the ethos that in addition to the

University's role of awarding formal academic qualifications to students, the University

must strive to instil in all students independent scholarly learning, critical judgement,

academic integrity and ethical sensitivity.

Please refer to the guild website the full charter of student rights, located at

http://www.guild.uwa.edu.au/info/student_help/student_rights/charter.shtml.

Student Guild contact details:

The University of Western Australia Student Guild

35 Stirling Highway

Crawley WA 6009

Phone: (+61 8) 6488 2295

Facsimile: (+61 8) 6488 1041

E-mail: enquiries@guild.uwa.edu.au

Website: http://www.guild.uwa.edu.au

11

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

Enquiries

General enquiries of a non-academic nature

General enquiries of a non-academic nature, such as enrolment questions and admission

requirements should be directed in the first instance to the Faculty Administrative Officer

(6488-2961) in the Student Centre, Law Link Building.

Enquiries of an academic nature

Questions of an academic nature, such as selection of electives and overloads should be

directed to the Associate Dean of the Faculty. Appointments to see the Associate Dean

can be made with Law School Reception. Enquiries that relate to the administration or

assessment of a particular unit should be directed to the unit co-ordinator.

12

Unit Outline

Week 1 - Introduction to the Law of Evidence

Prescribed reading

Arenson and Bagaric, page xxxix – xivi OR Waight and Williams Chapter 1.

Administrative issues

Class structure

Lecture times

Assessment

Some introductory comments…..

From the very beginning a student of evidence must accustom himself (herself!)

to dealing as wisely and understandingly as possible with principles which

impeded freedom of proof. He /she is making a study of calculated and

supposedly helpful obstructionism.

Maguire; Evidence – Common Sense and Common Law, pp 10-11

Evidence involves a study of the rules and principles regulating the collection and

presentation of facts and information in both civil and criminal court proceedings. In

summary the law of evidence is a system of rules which determine what evidence may be

admitted as proof of disputed facts at trial. These rules will impact on how a trial is

conducted, the evidence which may be admitted or excluded and for what purpose the

evidence may be used. Evidence may take the form of testimony, documents, physical

objects and anything else presented to the judge and/or jury.

The first thing to remember is that only relevant evidence is admissible. This sounds

logical however actually determining what is relevant has been the cause of much judicial

(and student!) consternation. Thayer in Preliminary Treatise on Evidence1 noted;

There is a principle - not so much of a rule of evidence as a presupposition

involved in the very conception of a rational system of evidence...- which forbids

receiving anything irrelevant, not logically probative. How are we to know what

these forbidden things are? Not by any rule of law. The law furnishes no test of

relevancy. For this, it tacitly refers to logic and general experience - assuming

that the principles of reasoning are known to its judges and ministers, just as a

vast multitude of other things are assumed as already sufficiently known to them.

Later the passage continues;

There is another precept…namely that unless excluded by some rule or principle

of law, all that is logically probative is admissible. This general admissibility,

however, of what is logically probative is not, like the former principle [that is

that irrelevant facts are inadmissible] a necessary presupposition in a rational

1

1898 Rothman Reprints, USA, 1969, pp 264-266, Aronson and Hunter at 672

13

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

system of evidence there are many exceptions to it…In an historical sense…

[w]hat has taken place, in fact, is the shutting out [of certain evidence] by the

judges of one and another thing from time to time; and so gradually, the

recognition of…[certain exclusionary rules]. These rules of exclusion have had

their exceptions; and so the law has come into the shape of a set of primary rules

of exclusion; and than a set of exceptions to these rules.

Therefore the prima facie rule is that all evidence that is relevant will be admissible

subject to certain exclusionary rules. Why do we need these exclusionary rules? Because

if we were to admit all evidence gathered in relation to a particular matter we may

encounter a number of difficulties. Firstly the evidence may be extremely prejudicial to

the accused or the defendant. Certainly we could argue that all evidence is prejudicial that is the idea - to build the case against a particular person. However what if the

evidence is extremely prejudicial but inherently unreliable, has been obtained illegally or

was hearsay? Think about the following example - Tom is on trial for the murder of Jerry.

Tom denies the allegations however the following evidence has been gathered by the

police;

testimony from Rastus, a habitual criminal who has an axe to grind with Tom. He

claims that Tom got drunk one evening and confessed to the murder,

testimony from Tom’s wife, Maggie,

a confession from Tom which was obtained after he was held in police custody for

24 hours without access to a lawyer,

evidence that Tom has previous convictions for car theft and drug dealing, and

testimony from Mrs Codd, the owner of the local fish and chip shop, that she

overheard one of her customers say to another that Tom was the murderer. The

customer cannot be found.

As you will have probably worked out yourself there are major problems with all these

pieces of evidence. What are these problems? Do you think the evidence should be

admitted? Why/why not?

We have seen that evidence that is otherwise admissible can be excluded by the operation

of the exclusionary rules. But it can also work the other way. There are also inclusionary

rules. Therefore take the example of Mrs Codd. Her evidence is hearsay as she merely

overheard another conversation and was repeating the contents of that conversation. The

customer participating in the conversation cannot be found - otherwise they could have

come to court to give direct testimony of their conversation and the reasons why Tom was

the murderer. (Unless of course that was hearsay too) The evidence would be excluded

under the rule against hearsay which is an exclusionary rule. However if the statement

could be said to be part of what is termed the res gestae evidence which may otherwise be

hearsay may be admissible. This is because in the circumstances the events were actually

held to be “part of the transaction”. Therefore, if Jerry was being assaulted outside Mrs

Codd’s shop and, during the course of the assault, a person ran into the shop and said,

“Tom is killing Jerry”, the statement may been held to be part of the res gestae and thus

be admissible. What if the assault had finished when the words were spoken? Sound

confusing? It is sometimes but you’ll soon get the hang of it. Rules, rules, rules but at

least the cases are mildly interesting.

There is also another factor which may tell against the admission of evidence. Otherwise

admissible evidence may also be excluded through the operation of a judicial discretion.

Therefore a piece of evidence may pass our requirements of relevancy but the judge may

14

Unit Outline

choose to exclude the evidence due to factors such as unfairness, the prejudicial effect of

the evidence or improper nature by which the evidence was obtained. So with this very

basic introduction lets proceed with the course…..

The law of evidence in Australia

The law of evidence in Western Australia is derived from a number of sources:

(i) the common law;

(ii) the Evidence Act 1906 (WA);

(iii) the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), and

(iv) miscellaneous legislation.

The Course of a Trial

We will now discuss some preliminaries (a bit of scene setting) and then address some of

the fundamentals of evidence. Basically we will be looking at the hurdles we have to

jump to ensure evidence, whether it be oral testimony, a document, an expert’s opinion or

whatever, is admitted and is considered by the finder of fact. In summary we will see that

evidence will be admissible and therefore capable of being received by a court in

circumstances where

- the evidence is sufficiently relevant and

- does not infringe an exclusionary rule and

- the evidence is not excluded by judicial discretion.

Sound simple? Let’s look at this in more detail…..

Prescribed reading

Waight and Williams Chapter 1 & 3 OR Arenson and Bargaric Chapters 1 & 2.

Court proceedings (again very brief)

Pleas

The jury

Witnesses

Examination in chief, Re examination, rebuttal and reopening

No case submissions

Summing up

The verdict and sentencing

Appeals

15

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

The judge and jury

The role of the judge and jury

The Voir Dire

Functions of the judge and jury

Judicial control of the jury

Aids to proof

The Burden and standard of proof

The legal burden,

The evidential burden,

The tactical burden,

The standard of proof,

No case submissions.

No case to answer

The standard of proof on a voir dire.

Direct evidence and Circumstantial evidence.

Note that direct evidence is evidence that establishes directly a fact in issue.

Circumstantial evidence is evidence of a fact from which a fact in issue can be inferred.

Comparison and examples

Circumstantial evidence

(i) Motive

Plomp v R (1963) 110 CLR 234 (W&W page 31

(ii) Relationship between accused and the victim

Wilson v R (1970) 44 ALJR 221 (W&W page 34)

(iii) Habit

Eichstadt v Lahrs [1960] QdR 487

Relevance and Admissibility

Prescribed reading

Arenson and Bagaric (A&B) Chapter 1

Additional reading

McNicol and Mortimer, Butterworths Tutorial Series – Evidence 3rd Edition Chapter 2

These articles are for general interest only – do not feel obliged to read them.

Roberts, Methodology in Evidence: Facts in Issue, Relevance and Purpose, (1993) 19

Mon LR 68

Hodgson, The Scales of Justice: Possibility and proof in Legal Fact Finding, (1995) 69

ALJ 73

In summary: Only evidence which is relevant is admissible.

Relevance is a matter of law for the judge.

The weight to be attached to admissible evidence is a matter of fact for the jury.

16

Unit Outline

What are we trying to prove?

Facts in Issue

The facts in issue are the main facts or subordinate (or collateral) facts. The main facts in

issue are all those facts which the plaintiff or the prosecution must prove in order to

succeed.

W&W state at page 1;

What the facts in issue are in a given case is determined first by the substantive

rules of law; secondly by the charge and plea in criminal cases and by the

pleadings in civil cases; and thirdly, by the manner in which the case is

conducted.

The main facts will include any further facts that the defendant or the accused must prove

in order to establish a defence or excuse, as opposed to simply denying the case made out

by his or her opponent.

Subordinate or Collateral Facts in Issue

The two most important examples of subordinate or collateral facts in issue are

those which reflect on the credibility of a witness and

those which affect the admissibility of certain types of evidence.

facts which affect the exercise of a judicial discretion.

W&W note (again page 1) that an alternative way of expressing the same requirement is

to say that evidence must be probative of a fact in issue. Evidence is directly relevant to a

fact in issue when the evidence itself bears on the probable existence or non existence of

that fact. Evidence is indirectly relevant to a fact in issue when it affects the probative

value of evidence said to be directly relevant to a fact in issue.

General Rule

As a general rule all evidence sufficiently relevant to a fact in issue or to the credibility of

a witness before the Court is admissible and all evidence that is not sufficiently relevant

should be excluded.

Relevance and Admissibility

What do we mean by “Relevance”?

Hollingham v Head (1858) 4CB(NS) 388, 140 ER 1135 (page 2 A&B)

Remember! Evidence will be regarded as admissible and therefore capable of being

received by a court in circumstances where

the evidence is sufficiently relevant and

does not infringe an exclusionary rule and

the evidence is not excluded by judicial discretion.

Logical relevance and legal relevance

17

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

Stephen, Thayer, McCormick and Wigmore - Students should note the table in McNicol

and Mortimer at page 18.

R v Buchanan [1966] VR 9

Horvath v R [1972] VR 533

*R v Stephenson [1976] VR 376 (page 4 A&B) Students should note the brief discussion

on page 9 A&B regarding the more recent application of the sufficient relevance

approach in R v Stajkovic [2004] VSCA 84 (18 May 2004)

For a Western Australian perspective on relevance and admissibility see Jeppe v R (1985)

61 ALR 383

There has recently been confirmation by the High Court as to the importance of relevance

as a key principle underlying the law of Evidence. Note that this case deals with s55 of

the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

*Smith v R (2001) 206 CLR 650

What were the facts in issue in this case?

What were the grounds of appeal?

What were the objections to the admissibility of the policemen’s evidence?

Note the comments of Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ

As is always the case with any issue about the reception of evidence,

identification evidence being no exception, the first question is whether the

evidence is relevant. No attention was given to this question in the arguments

advanced at trial, or on appeal to the Court of Criminal Appeal, but that question

must always be asked and answered. Further, although questions of relevance

may raise nice questions of judgment, no discretion falls to be exercised.

Evidence is relevant or it is not. If the evidence is not relevant, no further

question arises about its admissibility. Irrelevant evidence may not be received.

Only if the evidence is relevant do questions about its admissibility arise. These

propositions are fundamental to the law of evidence and well settled. They reflect

two axioms propounded by Thayer and adopted by Wigmore:

"None but facts having rational probative value are admissible",

and

"All facts having rational probative value are admissible, unless some specific

rule forbids."

In determining relevance, it is fundamentally important to identify what are the

issues at the trial. On a criminal trial the ultimate issues will be expressed in

terms of the elements of the offence with which the accused stands charged. They

will, therefore, be issues about the facts which constitute those elements. Behind

those ultimate issues there will often be many issues about facts relevant to facts

in issue. In proceedings in which the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) applies, as it did

here, the question of relevance must be answered by applying Pt 3.1 of the Act

and s 55 in particular. Thus, the question is whether the evidence, if it were

accepted, could rationally affect (directly or indirectly) the assessment by the

tribunal of fact, here the jury, of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue

in the proceeding.

18

Unit Outline

Was the evidence in this case relevant? Why/why not?

Do you agree with the majority?

Compare the judgment of Kirby J. Did Kirby J regard the evidence as relevant?

How does Kirby J describe the test of relevance pursuant to section 55?

Judicial discretion

Preliminary

Please note that our discussions regarding discretion at this stage will be

introductory. We will examine the various discretions as we proceed through the

course. As a result don’t worry if it seems a little unclear at the moment – you will

come to understand over the course of the semester.

The nature of discretion

Under both the common law and the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), a trial judge has a general

discretion to exclude otherwise admissible evidence. In a criminal case a trial judge has

the discretion to exclude legally admissible evidence if;

the prejudicial effect of the evidence outweighs the probative value of the

evidence,

the evidence is unfair to the accused (the fairness discretion), or

the evidence has been unfairly obtained (the public policy discretion).

Note the potential for overlap between the three discretions. R v Foster (1993) 113 ALR

1. Some commentators suggest the first two discretions could really be treated as one.

What do you think?

Discretion

General

discretion

Examples

Cth Evidence Act

S135 (nb applies to

civil and criminal

proceedings.)

Probative value

is exceeded by

prejudicial

effect

Fairness

discretion

Similar fact evidence,

Identification evidence

S137 (nb applies

only in criminal

proceedings.)

Evidence which is unfair to the accused due to

its unreliable/prejudicial nature eg the

circumstances under which a confession was

made.

Circumstances where evidence has been

obtained improperly, illegally or irregularly. For

example the methods used to obtain a

confession and/or the failure to follow statutory

procedures.

S 90 (nb applies

only in criminal

proceedings.)

Public policy

discretion

S138 (nb applies to

civil and criminal

proceedings)

We will discuss briefly the operation of these discretions. Students should generally refer

to *R v Swaffield; Pavic v R (1998) 192 CLR 159 (but don’t get too bogged down at this

stage!) We will look at the fairness discretion in much more detail in relation to the

admissibility of confessions (week 12) In relation to the public policy discretion please

read the following extracts from Bunning v Cross (1978) 141 CLR 54 and note the High

19

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

Court’s approach in relation to the public policy discretion per Stephen and Aicken JJ

pp79-80

The first material fact in the present case, once the unlawfulness involved in the

obtaining of the "breathalyzer" test results is noted, is that there is here no

suggestion that the unlawfulness was other than the result of a mistaken belief on

the part of police officers that, without resort to an "on the spot" "alcotest", what

they had observed of the appellant entitled them to do what they did. The

magistrate himself described what occurred as an unconscious trick, a phrase

which, whatever its precise meaning, is at least inconsistent with any conscious

appreciation by the police that they were acting unlawfully. This impression is

consistent with the evidence as a whole; no deliberate disregard of the law

appears to have been involved. The police officers' erroneous conclusion that the

appellant's behavior demonstrated an incapacity to exercise proper control of his

car may well have been much influenced by what they observed of his staggering

gait. Unlike the magistrate, they were unaware that the appellant suffered from a

chronic condition of his knee joints which could, apparently, affect his gait. If the

unlawfulness was merely the result of a perhaps understandably mistaken

assessment by the police of the inferences to be drawn from what they observed

of the appellant's conduct this must be of significance in any exercise of

discretion. Although such errors are not to be encouraged by the courts they

are relatively remote from the real evil, a deliberate or reckless disregard

of the law by those whose duty it is to enforce it.

The second matter to be noted is that the nature of the illegality does not in this

case affect the cogency of the evidence so obtained. Indeed the situation is

unusual in that the evidence, if admitted, is conclusive not of what it

demonstrates itself but of guilt of the statutory offence of driving while under the

influence of alcohol to an extent rendering him incapable of having proper

control of his vehicle To treat cogency of evidence as a factor favouring

admission, where the illegality in obtaining it has been either deliberate or

reckless, may serve to foster the quite erroneous view that if such evidence be but

damning enough that will of itself suffice to atone for the illegality involved in

procuring it. For this reason cogency should, generally, be allowed to play no part

in the exercise of discretion where the illegality involved in procuring it is

intentional or reckless. To this there will no doubt be exceptions: for example

where the evidence is both vital to conviction and is of a perishable or evanescent

nature, so that if there be any delay in securing it, it will have ceased to exist.

Where, as here, the illegality arises only from mistake, and is neither deliberate

nor reckless, cogency is one of the factors to which regard should be had. It bears

upon one of the competing policy considerations, the desirability of bringing

wrongdoers to conviction. If other equally cogent evidence, untainted by any

illegality, is available to the prosecution at the trial the case for the admission of

evidence illegally obtained will be the weaker. This is not such a case, due to the

mistaken reliance of the police, when they first intercepted the applicant, upon

what they thought to be their powers founded upon s. 66 (2) (c) of the Act.

A third consideration may in some cases arise, namely the ease with which the

law might have been complied with in procuring the evidence in question. A

deliberate "cutting of corners" would tend against the admissibility of evidence

illegally obtained. However, in the circumstances of the present case, the fact that

the appellant was unlawfully required to do what the police could easily have

20

Unit Outline

lawfully required him to do, had they troubled to administer an "alcotest" at the

roadside, has little significance. There seems no doubt that such a test would have

proved positive, thus entitling them to take the appellant to a police station and

there undergo a "breathalyzer" test. Although ease of compliance with the law

may sometimes be a point against admission of evidence obtained in disregard of

the law, the foregoing, together with the fact that the course taken by the police

may well have been the result of their understandably mistaken assessment of the

condition of the

applicant, leads us to conclude that it is here a wholly equivocal factor.

A fourth and important factor is the nature of the offence charged. While it is not

one of the most serious crimes it is one with which Australian legislatures have

been much concerned in recent years and the commission of which may place in

jeopardy the lives of other users of the highway who quite innocently use it for

their lawful purposes. Some examination of the comparative seriousness of the

offence and of the unlawful conduct of the law enforcement authority is an

element in the process required by Ireland's Case (1970) 126 CLR 321

Finally it is no doubt a consideration that an examination of the legislation

suggests that there was a quite deliberate intent on the part of the legislature

narrowly to restrict the police in their power to require a motorist to attend a

police station and there undergo a "breathalyzer" test. This last factor is, of

course, one favouring rejection of the evidence. However it is to be noted that by

the terms of s. 66 (1) the legislation places relatively little restraint upon "on the

spot" breath testing of motorists by means of an "alcotest" machine. It is

essentially the interference with personal liberty involved in being required to

attend a police station for breath testing, rather than the breath testing itself

(albeit by means of a more sophisticated appliance), that must here enter into

the discretionary scales.

The magistrate does not appear to have considered some of the above criteria. He

seems to have much relied upon what he regarded, we think erroneously, as the

"inherent unfairness" of what occurred and to have stressed the prejudicial nature

of the evidence, which was only prejudicial in the sense that it was by statute

made conclusive of the guilt of the appellant. He also does not seem directly to

have accorded any weight to the public interest in bringing to conviction those

who commit criminal offences.

In the end we believe that the balance of considerations must come down in

favour of the admission of the evidence.

Appeals from the exercise of Judicial Discretion In the marriage of Richards (1976) 10

ALR 230

21

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

Week 2- The Course of the Trial

Prescribed reading

A&B Chapter 4

COURSE OF EVIDENCE

Order of witnesses

Briscoe v Briscoe [1968] P 501

Exclusion of witnesses

R v Tait [1963] VR 420

The right to begin

In criminal cases where there is a plea of not guilty, the Crown has the right to begin

calling witnesses because there must be invariably some issue upon which the evidential

burden of proof is borne by the prosecution. Exceptions with regard to special pleas will

be discussed in lectures.

In civil cases, the plaintiff has the right to begin if he bears the evidential burden on any

issues raised by the pleadings including the quantum of damages.

THE ADVOCATES’ SPEECHES

In criminal cases, the prosecution opens, and then the defence is permitted to open. The

prosecution then calls evidence. The accused may or may not call evidence. At the end of

the trial, the prosecutor sums up leaving the accused with a right of reply.

In civil cases, assuming that he has the right to begin, the plaintiff opens the case to the

court, calls his witnesses and sums up if the defendant does not call witnesses. The

defendant then replies and thus has the final word. If the defendant does call witnesses,

the plaintiff does not sum up at the conclusion of his case, but the defendant opens his

case, calls his witnesses and sums up leaving the plaintiff with the right of reply.

PRESENTATION

Generally, the parties or their Counsel have the right to determine what witnesses they

will call and in what order they will call them. Note that in criminal cases the accused

should be called before any of his witnesses. He/she ought to give his/her evidence before

he/she has heard the evidence and cross-examination of any witness he/she is going to

call.

EXAMINATION IN CHIEF

The object of examination in chief is to obtain testimony in support of the version of the

facts in issue or relevant to the issue which the party calling the witness contends.

Remember your aim is to prove or disprove the facts in issue so witnesses are called to

support the facts you desire to establish.

22

Unit Outline

There are four main points to remember about examination in chief:

1. As a general rule, witnesses may not be asked leading questions;

2. A witness may refresh his memory by referring to documents previously prepared by

him

3. A witness cannot usually be asked about his former statements with a view to their

becoming evidence in the case or in order to demonstrate consistency.

4. A party may discredit his own witness only if the judge considers him to be hostile.

We will discuss all these points in lectures.

1. LEADING QUESTIONS

In examination in chief Counsel must not ask leading questions.

Leading questions are:

(a) Certain questions which suggest the desired answer or which put the disputed

matter to the witness suggesting a yes or no answer:

Example:

Did you see the car coming very fast from the opposite direction?"

This is a leading question. It is best to split it up, for example:

"Did you notice any traffic?"

"What direction did it come from?"

At what pace was it going?"

"What colour were the traffic lights?” or

(b) A question which assumes the existence of disputed facts (i.e. suggesting

evidence of facts not yet in evidence):

Example:

"What did you do after D hit you?"

"What did you do after D's car hit yours?

It may not yet have been decided whether in fact D had hit anybody by asking these

questions we are asking the witness about something that may have happened before it

was established it did in fact happen.

23

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

"How much did X pay you?" It may not have been established that a payment had been

made.

Leading questions are regarded as objectionable due to the possibility of collusion

between the person asking the questions and the witness or the impropriety in suggesting

evidence of facts that are not yet in evidence.

Also a question answerable some way other than a yes or no answer will still be

objectionable if it rehearses lengthy details which the witness might not otherwise have

mentioned and by this supplies him with suggestions.

Leading questions are allowed on introductory or undisputed matters in order to save

time. For example, name, occupation, address and other disputed matters. This approach

can be used by prior arrangement with the other Counsel or until it becomes too

controversial to continue questioning in this way.

Mooney v James [1949] VLR 22

Moor v Moor [1954] 1 WLR 927

Also, it is permissible to use leading questions to alert the witness' mind to the subject of

inquiry. Nicholls v Dowding & Kemp (1815) 171 ER 408. There is a list of exceptions

on page 250 W&W.

Answers to leading questions are not inadmissible in evidence however the method by

which they are obtained can rob them of their significance.

Students should refer to s29 and ss37-38 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

2. REFRESHING MEMORY

There are a number of reasons why a witness may need to refresh his/her memory while

testifying, for example, lapse of time since the occurrence of the event, the facts to be

testified may be complex etc. Try to remember what you were doing this time last week,

month, year… Even if something is hard to forget details can fade in your memory. On

the other hand what if you spend your life working in, for example, a hospital emergency

room with lots of cases and pressure? Would it be easy to recall a particular accident or

the nature of an injury after a lengthy period of time? If the witness does refresh his

memory a question can arise as to whether the document from which the memory is

refreshed must be produced to the court.

There are two different cases:

(i) Where the witness sits in the witness box and refreshes his memory directly inside the

court.

(ii) Where the witness refreshes his memory from material outside the court.

(i) Inside the Court

A witness is allowed to refer to a document to refresh his/her memory provided certain

conditions are fulfilled. It is not necessary that the witness must exhaust his/her memory

24

Unit Outline

as to the whole of his narrative -he can refer to notes each time he reaches a gap in his

memory. Baffingo l1957] VR 303: Hetherington v Brooks [1963] SASR 321.

cf R v Van Beelen (1972) 6 SASR 534.(W&W 253)

A witness may obtain the leave of the court to refer to a document for the purpose of

refreshing memory. Conditions upon which memory can be refreshed by reference to a

document:

(i) The account must be made or verified by the witness

*R v Van Beelen (1972) 6 SASR 534.

(ii) The account should be made at a time when the facts were fresh in his witness’s

memory. R v Van Beeean(1972) 6 SASR 534 per Sangster J at 537.

(iii) It must be produced to the Court or opposite party on demand.

Walker v Walker (1937) 57 CLR 630. MacGregor (1984) 1 QdR 256.

S32 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth)

(i) Outside the Court

You can refresh your memory outside the court. There are four situations listed in King v

Bryant [1956] QSR 570.

(a) The witness looked at the document because he had no recollection at all apart

from the document i.e. no genuine recollection" is revived.

In this case, it is not the witness’ evidence at all really and he is just proving the

document. That is not proper as the witness in effect is giving oral secondary evidence of

an available and unproduced document.

The document "verified and adopted" by the witness must be produced to make the

evidence admissible.

Alexander l1975] VR 741.

(b) The witness had no recollection until he looked at the document and his memory

was rekindled.

i.e. He looked at the document out of court and his memory is genuinely rekindled.

Therefore, when he gets into the witness box he gives evidence from memory. Here it

does not matter whether the document is lost, not produced etc. It is the oral testimony of

the witness the court may or may not believe. Admissible without need to produce the

report.

(c) Matters of which the witness has an actual memory of everything contained in

the report.

This is admissible without having to produce the report.

(d) Matters of which the witness had at all times retained an actual memory but are

not in report - i.e. he could not refresh his memory as it was not in the report.

25

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

This is admissible.

3. PRODUCTION OF THE DOCUMENT

There is an old rule that if a party calls to inspect a document held by the other party, the

other party is bound to put it in evidence if required. However, if it is simply to refresh

the witnesses memory, Counsel for the other party can just inspect the document without

making it evidence.

Walker v Walker.

Rule: If you as Counsel call for a document which has been used to refresh a witnesses

memory you will not find yourself in a Walker v Walker situation because you can call

for it, look at it and decide not to use it or cross-examine on it. BUT be careful to only

cross-examine on the parts used by the witness -if you go outside of this you must admit

the whole document into evidence.

MacGregor (1984) 1 QdR.

Kingston (1986) 2 QdR 114.

4. PRIOR CONSISTENT STATEMENTS

Students should read generally Waight and Williams pp 275-296.

Exceptions

Corke v Corke and Cook [1958] P 93

Nominal Defendant v Clements (1960) 104 CLR 476

5. HOSTILE WITNESSES

A hostile witness is one who is not desirous of telling the truth at the instance of the party

calling him. You can show the judge as a matter of law the witness is hostile and then

cross examine at length accuse him and use proof of evidence as a prior inconsistent

statement. It is a matter of discretion for the Court.

Bastine v Carew - in deciding to treat the witness as hostile the judge must have regard to

the witness’ demeanour the terms of an inconsistent statement etc

McCleland v Bowyer (1961) 106 CLR 95 (W&W 297) - a witness is likely to be hostile if

he exhibits a general reluctance to answer questions.

Price v Bevan (1974) 8 SASR 81 (W&W 300)

Driscoll v R (1977) 137 CLR 517

R v Hadlow (1991) 56 A Crim R 11

Western Australia

See sections 20-21

Judicial control over time spent in trial on examination and cross examination of

witnesses.

Order 34 Rule 5A SCR(WA) (This also applies to cross examination)

26

Unit Outline

CROSS EXAMINATION

There are two objects of cross-examination:

1. To weaken, qualify or destroy the case of the opponent.

2. To establish the party's own case by means of his opponent's witnesses.

A witness may be asked not only as to the facts in issue or directly relevant thereto bud

all questions which though otherwise irrelevant tend to impeach his credit.

R v Chin (1985) 157 CLR 671

The rule in Browne v Dunn:

1. Any matter upon which it Is proposed to contradict the evidence in chief of a witness

must be

put to him so he might have the opportunity to explain the contradiction. Basically, if you

want

to contradict a witness, do it clearly.

2. Failure to do this may be held to imply acceptance of the evidence in chief.

3. This is a rule of fairness which is strictly enforced.

4. It does not apply if it is manifestly obvious due to the pleadings and the trial that the

witness is being impeached.

5. The rule in Browne v Dunn is not as strict as regards the accused because is has been

through the committal and the trial and knows what has been saw which may be used to

impeach his credit.

An example is Allied Pastoral Holdings v The Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1983]

1 NSWLR 1

The Federal Commissioner of Taxation did not examine six witnesses with regard to a

specific provision which the Commissioner wanted to rely on his submissions. In other

words, the witnesses have no chance to explain.

Hurt J identified the rule in Browne v Dunn and outlined the reasons for it:

1. If you do not put to the witness specifically that he is wrong (i.e. you are contradicting

him) you deny his chance to explain under cross examination.

2. The rule gives the party calling a witness an opportunity to call corroborative evidence

which

in the absence of such a challenge is unlikely to be called.

27

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

3. The witness can explain/qualify his own evidence In the light of contradiction of

which warning had been given and also if he can explain/qualify other evidence of which

the challenge is based.

Therefore, if as Counsel you:

(i) Fail to cross examine; or

(ii) Fail to put your parts of the case which contradict him but in addition you call other

evidence which contradicts him or invite the tribunal of fact to reject the evidence of the

witness when you fail to cross-examine him, you are in breach of the rule.

The rule applies to both civil and criminal proceedings.

Breach of the rule may result in an opponent being able to recall a witness even though

the case is closed

FINALITY OF ANSWERS ON COLLATERAL MATTERS

Counsel can cross-examination on

1. The issues;

2. Collateral matters.

When Counsel cross-examines on collateral matters he or she is stuck with the answers he

has given. The reason for this is to stop a multiplicity of issues confusing the matter.

What is a collateral matter?

Attorney General v Hitchcock (1847) 1Exch 19

Test - per Pollock C B:

If the answer of a witness is a matter which you would be allowed on your own part to

prove in evidence - if in had such a connection with the issues that you would be allowed

to give n in evidence - then it is a matter on which you may contradict him. i.e. if it is not

of this type It is collateral and consequently Counsel must accept the answer as final.

The most obvious of the collateral matters is the credibility of a witness.

Piddington v Bennett and Wood Pty Ltd (1940) 63 CLR 533.

A witness for the plaintiff in an action for damages arising out of an accident was asked

how he could account for his presence at the place where the accident occurred. He said

that he had been doing business at a particular bank for a Major Jarvie. The High Court

ordered a new trial on the grounds that the trial judge had wrongly permitted the manager

of the bank to give evidence that no business had been done for Major Jarvie on the day

in question.

Per McTiernan J:

28

Unit Outline

This evidence could throw no light whatsoever on the question whether the witness had

seen the accident or not. It could discredit the witness but it was incapable of

contradicting any act upon which proof of the opportunity which the witness had of

observing the accident depended."

cf Latham CJ (dissent):

The question whether the witness has gone to the bank for Major Jarvie had considerable

bearing on the truth of his evidence that he had been at the scene of the accident.

NB exceptions.

For a recent case from Western Australia with a detailed consideration of the collateral

evidence rule see Nicholls v R; Coates v R [2005] HCA 1. You should read this.

1. The fact that a witness has been convicted of a crime (s.23 Evidence Act (WA)).

Livingstone (1984) QdR

2. The fact that the witness is biased in favour of the party calling him.

Umanski (1961) VR 242

Smith v R (1993) 9 WAR 99

3. The fact that the witness has previously made a statement inconsistent with his

present testimony.

4. The fact that the moral character of the witness is such as to militate against his/her

telling the truth

5. Mental or physical ailments which may influence the person giving evidence

Toohey v Metropolitan Police Commissioner (1965) AC 595

RE-EXAMINATION

Students should refer to the extract from Mr Justice Wells in Waight and Williams at

page 333.

Re-examination must be confined to matters arising out of the cross-examination and new

matters may only be introduced with the leave of the judge.

R v Connell (1994) 12 WAR 133 at 209-210 and 216-217

Wojcic v Incorpoated Nominal Defendant [1969] VR 323 W&W 334

RE-OPENING

Hansford v McMillan [1976] VR 743 (W&W 338)

REBUTTAL

29

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

There is a general principle of practice, not a rule of law, requiring all evidential matters

the Crown intends to rely on as probative of the guilt of the defendant to be adduced

before the close of the prosecution's case.

Evidence in rebuttal will only be allowed if it relates to a maker which the prosecution

was unable to foresee and this is stringently applied.

Of traditional importance is the relevance of such evidence to the defence of alibi. See

Killick vR (1981) 56 ALJR 35 (W&W 339).

The defence of alibi had been raised although the Crown had called no evidence in chief

to rebut the alibi. However, after the defence case had been closed evidence was called to

show that the accused account of his alibi was untrue.

By majority the High Court ordered a new trial for the following reasons:

1. Because of the earlier conduct of the case (prior to committal proceedings the accused

had consistently put forward the defence) the Crown should have foreseen that the

accused would rely on the alibi at the trial.

2. The submission that the evidence in rebuttal would have been admissible as evidence

in chief was rejected. The prosecution cannot give evidence in this proof of an alibi which

the accused has no intention of raising. R v Natasien [1972] 2 NSWLR 227 (W&W page

341)

THE FAILURE TO CALL EVIDENCE

Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298

Booth v Bosworth [2001] FCA 1453 (17 October 2001)

Weissensteiner v R (1993) 178 CLR 217

See too section 20 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth)

30

Unit Outline

Week 3 -Competence and compellability of witnesses

To date we have examined the preliminary concepts of relevance and admissibility.

We have also introduced you to judicial discretion (but there is much more to come

here!). Now we are going to start looking at the evidence itself. Think of this. We

have a prospective witness who is prepared to testify. The testimony is directly

relevant to a fact in issue. Sounds good? But…our witness is only eight years old. Or

our witness is married to the accused person. Do you see a potential problem here?

Why?

Prescribed reading

A&B Chapter 3

Waight and Williams Chapter 2

Introduction

General concepts

Competence and compellability vs privilege. Please note privilege will be dealt

with in week 10.

Students should refer generally to sections 6-17, 106A-S Evidence Act 1906 (WA).

In summary:

Competence

A witness who is competent may lawfully be called to give evidence. As a general rule all

persons are competent to testify BUT there are exceptions in respect of witnesses;

- who do not believe in a deity,

- children,

- persons who are intellectually impaired,

- the accused’s family, and,

- the accused.

Compellability

A witness who is compellable may be lawfully obliged to give evidence. Again as a

general rule a witness who is competent is also compellable BUT there are again

exceptions involving;

- the accused’s family,

- the accused,

- sovereign and diplomatic immunity.

31

Evidence Study Guide Semester 2 2007

Oaths and affirmations generally

Witnesses usually give evidence after swearing an oath on the bible. In Western

Australia, if a person objects to being sworn and states as his or her ground for doing so

either that he or she has no religious belief or that the taking of an oath is contrary to his

or her religious belief, he or she is permitted to make a solemn affirmation: ss. 610,97,99,100A Evidence Act 1906 (WA), ss70-71 Justices Act 1902(WA) If the proposed

witness has a religious belief which is not opposed to the taking of oaths, but declines to

take the usual form of oath or declines or is unable to say what form of oath binds him or

her or he or she is unable to take a binding oath there is provision for the judge to declare

in what manner the evidence of such person shall be taken. This will usually be by

affirmation. Students should read generally ss97-106 Evidence Act 1906 (WA)

The Consequences of giving false evidence

Cabassi v Vila (1940) 64 CLR 130 (W&W 42)

Competence

Witnesses who do not believe in a deity

Under the common law persons who did not believe in a deity were not competent to

testify. Today, such persons are competent to testify upon making a solemn

affirmation. Refer to the paragraph above for reference to the relevant statutory

provisions.

The evidence of children

Under the original rules of evidence children were not regarded as competent witnesses.

This situation was amended by legislation. Today children are competent witnesses

subject to the matters discussed below. It is important for students to note the provisions

of section 106A – 106R of the Evidence Act 1906(WA) regarding protections available for

child witnesses and other persons classified as “special” witnesses. Also, please be

aware of significant amendments in 2004 regarding these provisions.

The common law position

R v Brasier (1779) 168 ER 20 “A child can give evidence on oath if he has sufficient

knowledge of the nature and consequences of an oath”

Omychund v Barker (1744) 125 ER 1310 “Nothing but a belief in God and that He will

reward or punish us according to our desserts is necessary to qualify a man to take an

oath”(Sorry about the language – old cases.)

R v Brown [1977] QdR 220 (A&B 33) but compare Re Attorney General’s Reference of 1993

(1994) 73 A Crim R 567

Western Australia

Students should commence their study of this area by examining the various definitions in

section 106A.

A child under the age of 12 years will be permitted to give sworn evidence if it is understood by

the child when testifying that the giving of evidence is a serious matter and that he or she is

under an obligation to tell the truth that is over and above the ordinary duty to tell the truth. (See

section 106B) R v Stephenson (2000) 23 WAR 92

32

Unit Outline

Students should familiarise themselves with sections 106A – 106S Evidence Act 1906 (WA

and bring a copy of the legislation to lectures.

When is a child competent to give sworn evidence?

If a child is under the age of 12 years when is the child competent to give sworn evidence?

Section 106B(1),(2)

In Hamilton v R (you do not have to read this case – the extract below is sufficient)

unreported; CCA SCt of WA; Library No 970082; 4 March 1997, Malcolm CJ said:

"In my opinion, it is most important that the jury should hear the child's answers

and have the opportunity to observe the demeanor of the child when questioned

by the Judge. These matters are relevant to the weight which the jury may attach

to the evidence of the child."

“…...Because of the significance of the enquiry, it is important that it be

sufficiently detailed to enable an opinion to be formed with confidence."

Malcolm CJ then explained what he meant by a "sufficiently detailed" enquiry:

"First of all, it must be remembered that upon first being questioned by a Judge a

child is likely to be very nervous and, possibly, frightened. Consequently, in my

opinion, it is desirable that the child be first asked a series of questions designed

to overcome that nervousness such as questions about age, birthday, the school

attended, the grade the child is in and the number of children in the class. If

leading questions are avoided, this gives the child the opportunity to give a

substantive answer. It may also be helpful to enquire about any particular friends

at school, whether the child has a favourite subject or a favourite television