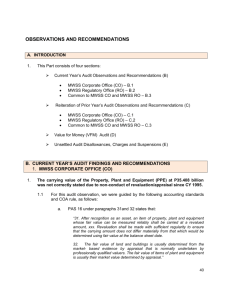

Monitoring mwss water rates_corral-oct01

advertisement

MONITORING THE MWSS PRIVATIZATION: Water Rates Violeta Q. Perez-Corral, NGO Forum on ADB, 4 October 2001 The management of Manila’s water and sewerage distribution system (MWSS) was privatized in August 1997 in what has largely been touted as a ‘successful’ water privatization, and the largest to date in the Asia-Pacific region. The International Finance Corporation (IFC), the World Bank’s private sector arm, was adviser1 to the privatization, which resulted in two 25-year concessions (east and west) competitively bid.2 Bidding was based on the lowest average tariff to cover operations, investments and profit. All bids came in below the prevailing tariff of PhP8/78/m3 ($0.00/m3). The winning bids were Benpres/Suez-Lyonnaise (Maynilad Water Services or MWS) for the west at PhP4.97/m3 ($0.12/m3) and Ayala/Bechtel/Northwest (Manila Water Company or MWC) for the East at PhP2.32/m3 ($0.06/m3). Under separate concession agreements, Maynilad and MWC have 25 years to rehabilitate and operate the water system, reduce physical losses, check illegal usage and expand service coverage. From the onset, civil society groups have challenged this so-called success due to the nondemocratic and non-transparent nature of the privatization process, the lack of a ‘full-options approach’, and massive job displacement which ensued. In recent years, protests have greeted regular water rate increases sought by the two private concessionaires. These water rate hikes will only bring added burden, especially to urban poor households and the women who manage these households and who are still struggling to keep pace with the aftermath of the 1997 Asian crisis and expected global recession following the September 11 attacks in the US. The 'privatization' of water is a consequence of the now prevailing view that water is an economic good rather than merely a social good. This is contrary to the long-held notion of water as a free natural resource on which whole cultures and livelihoods of rural and indigenous communities are based. International financial institutions like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and Asian Development Bank have been primarily responsible for this new paradigm, which also now looks at water as a tradable commodity. Regimes of 'tradable water rights' and 'water uses of higher value' in the near future will sell water to the highest bidder, and poorer men and women will no longer be able to compete. Where does ADB fit in? The ADB has played a leading role in the development of the country's water supply and sanitation sector since 1973, financing 13 water supply projects and a sewerage project and 13 technical assistance grants. Over the past ten years, the ADB has poured several loans amounting to roughly $426 million to improve the water supply and distribution of the MWSS; to other water districts nationwide, ADB poured in a total of $131 million.3 The Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS) advisory team consisted of IFC (World Bank), Sogreah/BCEOM (France) technical consultants, NERA (UK) regulatory/economics consultants, Cleary, Gottlieb & Hamilton (U.S.A) and ACCRA (Philippines) legal consultants, Punongbayan & Araullo (Philippines) and Ernst & Young International (U.S.A) financial accounting consultants and Ogilvy and Mather (U.S.A.) public relations consultants. The cost of the whole process was $5.8 million, made up of $3.8 million in advisor and consulting fees and $2.0 million in success fee. A technical assistance grant of $1.0 million was provided by the French government for the Study. 1 Four consortia, each 60 percent local and 40 percent foreign were prequalified for bidding. They were Aboitiz Equity Ventures (Philippines) with Compagnie Generale des Eaux (France); Ayala Corporation (Philippines), with Bechtel Enterprises (U.S.A) and Northwest Water (UK); Benpres Holdings Corporation (Philippines) with Lyonnaise des Eaux (France) and Metro Pacific (Philippines) with Anglian Water International (UK). All four consortia bid on both East and West concessions but no one consortia was allowed to win both. 2 3 Barring IFC’s strategic advisory role in the MWSS privatization, the World Bank was not as active in the MWSS, with Page 1 of 11 In September 1999, the ADB approved a $170 million loan to Maynilad Water to improve and expand water distribution and wastewater treatment services. This is the Bank's first assistance to a privatized water and sewerage utility. Maynilad has assumed implementation of two ADB-funded MWSS projects – (a) $130 million Angat Water Supply Optimization project and (b) $31 million Manila South Water Distribution project -- to increase water supply, with a new water source expected from the $92-million Umiray-Angat Transbasin, another ADB-funded project. The ADB private sector loan to Maynilad is part of a $350 million debt package being raised by the water firm to meet its financing needs up to the year 2002. Other ADB co-financiers include the European Investment Bank and a syndicate of international commercial banks. Equity financing of $135 million supposedly will be provided by Maynilad's sponsors -- i.e., Benpres Holdings Corporation of the Philippines, Suez-Lyonnaise and Lyonnaise Asia Ltd. of Singapore. In other words, at least half of the financing requirements needed by the MWSS private concessionaires was raised from inter-governmental public funds (ADB) in what may be a case of the private 'crowding out' the public. A $0.6 million Technical Assistance (TA),‘Capacity Building for the MWSS Regulatory Office’, is in the pipeline. Another $0.15 million TA is also in the offing on Laiban Dam to augment water supply, which may be as big as the controversial San Roque Dam and implemented through BOT; funding required is initially estimated at $1 billion. Moreover, two other TAs on (Small Towns) Water Supply and Sanitation are in the pipeline. What happened to water rates? Grounds for rate increase. Water rates can be adjusted in three ways: (i) based on the consumer price index (ii) extra-ordinary price adjustment (EPA) for the financial consequences of unforeseen events beyond control of the concessionaire and (iii) rate re-basing adjustment (every five years). There are 11 grounds for EPA in the Concession Agreements; these include inflation (to be determined by the consumer price index), foreign currency fluctuations of more than 2%, and force majeure such as El Nino. The first rate re-basing may take place either in 2003 or 2008, largely on the discretion of the MWSS Regulatory Office (RO). Water rates will then be set at a level that will permit the concessionaires to recover, over the 25 year term of the concession, all operating, maintenance and investment expenditures prudently and efficiently incurred. The rates of return on these expenditures for the remaining term shall be in line with rates of return being allowed from time to time operators of long standing infrastructure concession agreements in other countries having a credit standing similar to that of the Philippines. Annual water rates. Table 1 shows the increase in water tariffs (basic charge) since 1997. The two private concessionaires filed its first petition for rate increase barely a year after privatization, citing ‘extraordinary circumstances’. Vigilance on the part of citizens’ groups, however, ensured that the amount of water rate hikes sought by Maynilad and Manila Water were not granted by the MWSS RO. The EPA component in annual rate increases had only been an insignificant percentage (2-6%) of the total tariff increase granted. (See Attachments A and B for rebuttal statements submitted by oppositors – e.g., ordinary consumers, Freedom from Debt Coalition.) only a $50-million loan in 1996 to finance the rehabilitation of the sewerage network and the Ayala treatment plant. Over the past 10 years, the World Bank has provided loans amounting to $171 million in support of PSP in LGU water districts outside Metro Manila; ADB's contribution is $131 million. Page 2 of 11 Table 1. Average tariff rate (PhP/m3). MAYNILAD Pre-privatization 1997-1998 1999 2000 2001 (Source: MWSS Regulatory Office, 2001) MANILA WATER PhP 8.78 PhP 4.96 PhP 5.80 PhP 6.13 PhP 6.58 PhP 2.32 PhP 2.61 PhP 2.76 PhP 295 Aside from the basic charge, other fees are also collected in the monthly water bills – a fixed cost of PhP1/m3of water consumed for currency exchange rate adjustment (CERA), environmental and sewerage charges, and miscellaneous fees. Today, a household consuming an average 30 m3 of water per month pays PhP15.54/m3, or PhP466.20. 1998: Rate dispute between MWSS RO and Manila Water. . In 1998, a major dispute has arisen between Manila Water and the MWSS over tariffs. The concessionaire sought a PhP2.23/m3 increase in its tariff over a period of four years and P0.97/m3 for the next 20 years; this is equivalent to a PhP2.06/m3 increase for the whole concession period. The MWSS granted only PhP0.04/m3 or a mere 6% of the increase sought. Manila Water sought international arbitration4 in September 1998 which promptly ruled in favor of the private concessionaire. The MWSS appealed this ruling at the Philippine Court of Appeals; by some mysterious twist of events, this appeal was recently withdrawn. The MWSS-Manila Water dispute is related to the so-called ‘appropriate discount rate’ or ADR which the MWSS had set at a constant 5.2% for Manila Water, based on the concessionaires’ 1997 financial model and bidding assumptions. (ADR for Maynilad was 10.4%.) In May 1998, Manila Water claimed a market-based ADR of 18% which the MWSS RO did not allow. Had Manila Water used the 18% ADR in 1997, it would not have won the bid. Now that MWSS withdrew its appeal, a major consequence would be the retroactive increase (to 1998) in water rates, and significant rate increases to be granted to Manila Water in future. 2000-01: ‘Accelerated’ EPA sought by Maynilad. Last year, Maynilad filed a petition for an ‘automatic currency exchange rate adjustment’ (autoCERA) and consequent rate increase of PhP4.75/m3. This increase in water rate will allow Maynilad to recover some PhP2.7 billion ($52 million) of foreign exchange losses due to peso devaluation covering the period August 1997 to endDecember 2000. (Maynilad absorbed 90% of MWSS’ foreign-denominated loans.) Maynilad claims to be experiencing these huge losses and severe liquidity and bankability problems as a result of the Asian crisis and the more recent impeachment trial. Since March 2001, Maynilad halted its monthly concession payments of PhP200 million to MWSS, in what is tantamount to a situation holding the MWSS hostage to ensure that Maynilad’s petition is acted on favorably. An overzealous MWSS Chief Regulator (now resigned, and amidst allegations of bribery) ensured the signing of a so-called Memorandum of Cooperation (MoC) between Maynilad and the MWSS in June 2001. The MoC would allow Maynilad to: (a) accelerate the recovery of its foreign exchange losses and subsequently impose a rate increase amounting to P4.75; (b) scale down Maynilad’s performance targets, and (c) lower the billed volume from the levels in Maynilad’s financial model (on which basis it won the bid for the west zone), to actual levels.5 Cost of arbitration was roughly $1 million (~P40 million in 1998-99), with half the fees going to the international arbitrator. It is unsure who bore the costs of the international arbitration. 4 In particular, lowering the billed volume to Maynilad’s actual volume would in effect reward Maynilad for its inefficiency and mismanagement, since the latter account for a significant part of Maynilad’s current high levels of non-revenue water and therefore low billed volume. 5 Page 3 of 11 What the MoC approved in effect was an ‘accelerated’ EPA and the deferment by Maynilad of its service obligations (e..g., almost 100% coverage by 2006, which should also include urban poor households; decrease in ‘non-revenue water’; sewerage/sanitation services). In effect, the MoC is a case of ‘dagdag presyo, bawas serbisyo’ (or, increased prices for less services). The ‘accelerated EPA’ under the MoC will allow Maynilad to recover 95% of its foreign exchange losses upfront (within 18 months), and 5% over the remaining life of the 25-year concession. Civil society groups have again raised strong protests over the legality of the MoC, citing that the MoC has violated the original concession agreement and undermined the integrity of the 1997 bidding process.6 Maynilad’s huge losses are a result of its inefficiency and mismanagement.7 Hence, government should not allow the rate increase which bails out the water firm and passes on the costs to consumers, especially to women in customer-households who have to manage tighter budgets also as a result of the same peso devaluation. Due to the strong opposition, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo ordered that the MoC be reviewed. The most recent news, however, is that Maynilad will finally be getting the increase it has sought. It will also be allowed to implement a so-called foreign currency differential adjustment (FCDA) – the same banana as an autoCERA but termed differently. Thus, Maynilad will be allowed to recover 95% of its forex losses (for August 1997-December 2000) upfront within the next 18 months. Thus, the same household consuming a 30 m3 of water monthly will now be paying PhP592.50 from the previous PhP466.20, or an increase of 64%. Manila Water also filed its own petition for rate increase, at P1.24/m3, and has now demanded ‘equal treatment’ as the Maynilad. More rounds of increases. In the near future, at least two instances of rate increases are foreseeable: 1. In January 2002, consumers may again be confronted with another rate increase due to EPA – this time from grounds aside from foreign exchange. Both private concessionaires have already griped and petitioned for increases in 2002 due to ‘cost over-runs’ which they claim are a result of government delay in the completion of the Umiray-Angat Transbasin project which augments the water supply in Metro Manila. The fact that both concessionaires have not completed their own obligations re laying down additional pipelines and addressing losses due to non-revenue water anyway lends little credence to this claim, however. 2. Since the stage has already been set, a rate re-basing is likely to occur sooner (in 2003) rather than later (2008). This would mean another round of increase and more protests. This accelerated EPA is tantamount to the AUTOCERA (automatic currency exchange adjustment) petitioned by MAYNILAD - and thwarted by the MWSS RO! -- in the past. Granting an AUTOCERA would have allowed MAYNILAD to completely escape prudential regulation with regard to foreign currency borrowing, and hence violated the spirit and principle of the1997 Concession Agreement. Moreover, by this single act, the MWSS has compromised the integrity of the 1997 bidding process which has the effect of 'changing the rules' midstream and rewarding bid winners making wrong financial assumptions. 6 For instance, Maynilad’s ‘non-revenue water’ (NRW) which has been increasing—from 60% in 1998 to 66% last year—rather than decreasing (as projected in its financial model), could still be reduced, with better management. At present, for every three cubic meters of water it produces, Maynilad earns from only one. 7 Page 4 of 11 Co-oprivatization – An alternative to water rate hike All through the period of its appeal for water rate hike, Maynilad -- through its giant media conglomerate -- has appealed to the Filipino public’s emotions in portraying the choices only between having water and no water at all. To counter Maynilad’s water rate increase, an alternative and win-win ‘co-oprivatization’ solution was set forth by the Freedom from Debt Coalition (FDC) in September 2001, with endorsements from many Philippine-based groups. Co-oprivatization would enable consumers to buy into Maynilad and participate in its ownership – ‘Instead of simply paying more for a water rates increase without getting anything in return, consumers would develop their stake in Maynilad and eventually benefit from it not only as consumers but also as owners.’ Co-oprivatization is also an alternative way of generating cash from consumers that is at the same time long-term capital, based on the principle of simply charging them a price that they can bear and afford. Through co-oprivatization, Maynilad’s capital position would be beefed up enough to improve its creditworthiness and thereby enable Maynilad to procure medium to long term loans for its capital expenditures. Co-oprivatization would strengthen Maynilad’s accountability to consumers cum part-owners of the privately-managed enterprise. In addition, there are clear macroeconomic benefits of a large-scale application of cooprivatization, as follows -- Development of capital markets, with the introduction of new debt instruments and the emergence of a mass base of investors; Creation of a base of forced savings as millions of consumers regularly and reliably plunk equity on the basis of their consumption; Emergence of management discipline tools to check institutional management and investors (failure to perform efficiently and effectively results in dilution of their position and control); Real possibility of a diminished fiscal burden with greater consumer accountability. From the FDC position paper: “In the final analysis, the option is not between having water and the more expensive anti-poor alternative of having no water. It is now a matter of economic justice, of equitably sharing the risks and benefits of a precious commodity and becoming more pro-poor and pro-people than ever.” REFERENCES: A.C. McIntosh and C.E. Yniguez, Privatization of water supplies in ten Asian cities, January 2000, Asian Development Bank Ma. Teresa Diokno-Pascual, Jude Esguerra, Rhoda Viajar and Joffre Balce, Co-oprivatization, not Rate Hike, the Answer to Maynilad's Woes', Freedom from Debt Coalition, September 2001. Violeta Q. Perez-Corral, The WB-IMF/ADB at Work in the Philippine Privatization Program, Freedom from Debt Coalition, August 2000. Page 5 of 11 ATTACHMENT A 29 May 1998 MR. FERNANDO VICENTE Chief Regulator, MWSS Regulatory Office Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS) 4/F Administration Building, MWSS Complex Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon City 1105, Philippines Telefax: 435-8898 RE: ANSWER TO PETITION FOR EXTRAORDINARY PRICE ADJUSTMENT (EPA) OF MANILA WATER COMPANY AND MAYNILAD WATER SERVICES We, the undersigned oppositors, manifest our strong and vehement objections to the petition for extraordinary price adjustment (EPA) filed by Manila Water Company (Ayala) and Maynilad Water Services (Benpres) for the following reasons: 1. ON PETITIONERS' CLAIM FOR REDUCTION OF WATER SUPPLY BROUGHT ABOUT BY EL NINO. The claim of the 30-35% water loss brought about by El Nino does not translate to a showing of "significant additional cost". Because petitioners operate commercially, receipt reductions or lost revenues cannot be subsidized through an extraordinary price adjustment (EPA). The consumers cannot be made to subsidize management mistakes. Significant additional cost and not lost revenues is one of the basis for claiming EPA. Petitioners merely present lost profits which allegedly has been exacerbated by El Nino but it is not receipt reduction which is of the moment in claiming EPA. Petitioners operate commercially and therefore suffer the normal risks of business, including loss of profits. The proper grounds of EPA is significant additional costs that are not covered by insurance which have not been shown by Petitioners in the documents. It is noteworthy that peasants insure their crops against drought, and, considering that the worst instance of EL Nino took place in 1993 and corporations that submitted their bids were advised to factor in the effect of El Nino into their respective bids, the failure of the Petitioners to comply with such an advice and/or obtain such insurance coverage is a management call within their control and not force majeure. They must therefore suffer any consequent commercial loss for it. Further, Petitioners have not submitted, and therefore must now submit, their income statements to show the nature and extent of their commercial operations and how the element of EL Nino has factored into significant additional costs that are not covered by insurance. These income statements must show dividends that have been awarded to stockholders, salary perks, incentive bonuses to top management, consultancy fees, especially those that are dollar-denominated paid to foreign consultants by Petitioners. This will give us an appreciation of what would constitute admissible significant additional costs that are not covered by insurance. It is not sufficient to disclose cash flows as an element of establishing significant additional costs where you are dealing with a private for-profit utility and not a public utility. Further, assuming without admitting that El Nino actually resulted in significant additional costs that are not covered by insurance to the Petitioners, that adverse effect lasted only for at most five months from January to May 1998. Projected additional costs cannot be claimed for an alleged continuing El Nino during the effectivity of the EPA requested by the Petitioners, which is four years in the case of Ayala, and twenty-five years in the case of Benpres. EL Nino is a meteorological phenomenon which occurs within a cycle of seven years within a period of twenty-five years. Page 6 of 11 2. ON PETITIONERS' CLAIM FOR CHANGE IN GOVERNMENT REGULATIONS, RULES OR ORDERS AFFECTING RAW WATER ALLOCATION. Lowered release rate of Angat Dam does not constitute a change in government regulation, rule or order sufficient to justify an EPA. There is a standard operating procedure governing water release contingent on the water levels at Angat Dam. Petitioners are aware of this. The claim for stable water supply as a bidding assumption is necessarily dependent on the water level of Angat Dam. Stability and perpetuity are not one and the same. Any business enterprise like the Petitioners' would factor any reduction of the supply of goods or services that they are selling commercially, even if they are free to begin with, as in the case of water as a natural resource. Precisely, the National Water Crisis Act of 1995 was a recognition of the El Nino phenomenon and any of its consequent results, including the reduction of water supply from Angat Dam. The historical antecedent that led to the privatization of MWSS is El Nino, therefore the Petitioners cannot now pretend to factor it in as a basis for EPA. 3. ON PETITIONERS' CLAIM FOR MATERIAL DETERIORATION OF WATER DISTRIBUTION NETWORK. Material deterioration of the water distribution network is not a natural consequence of the reduction of water release due to El Nino. Natural deterioration is expected which is accelerated by a lack of maintenance. As a matter of fact, folk wisdom says that the new distribution networks are the illegal connections. Has any annual Public Performance Audit been made to justify such claims? To claim deterioration, there has to be a showing of the status of the distribution network before and after privatization. All claims presented by Petitoners have merely been anecdotal and self-serving, such as pictures of uniformed and ID-ed personnel with airconditioned service vehicles. (No wonder they are complaining of increased costs!). 4. ON PETITIONERS' CLAIM FOR PESO DEVALUATION. Petitioners' claim for peso devaluation since July 1997 has not been rationalized as a basis for EPA. Nine months have already passed, and they have not established in their petition their actual monthly drawdowns and payments, as well as reflect the average monthly devaluations for foreigndenominated loans. The assumption implied in the Petitioners' claims is that they were doing the drawdowns and undertaking payments from the get-go of the Concession Agreement. They may not now seek to apply the lump 52% average devaluation by the Manila Water Company and 40% by Maynilad Water Services for the enitre period of nine months covered for the loans and other operating costs, especially in the light of their 10:90 ratio in foreign debt servicing. Cash flow statements are not sufficient for Petitioners to establish effect of devaluation as a basis for EPA. Corporate income statements must be presented, including the schedule of monthly drawdowns and repayments. They should indicate the foreign-denominated obligations of their partner investors whether as dividends or in whatever form of return or income or earmarks. Therefore, full financial disclosure must be compelled by the Regulatory Office to establish the validity and competence of the financial data already presented. 5. ON PETITIONERS' CLAIM FOR PROJECTED HIGHER OPERATING COSTS BASED ON A PROJECTED COST OVERRUNS OF AN EXISTING PROJECT, I.E., UMIRAY-ANGAT TRANSBASIN PROJECT (UATP). There is no such basis for EPA since it is merely anticipated or imagined, not an actual significant addtional cost. The Concession Agreement does not refer to such prospective cost. Further, Maynilad's projected additional operating and capital expenditures cannot be utilized as basis for the EPA as it is still prospective and in the future as a prognostication. These matters are not referred to at all in the Concession Agreement. Page 7 of 11 6. ON AYALA'S CLAIM OF SIGNIFICANT INCREASE IN EMPLOYEE SALARIES. There is no basis for invoking this in the present petition. Nothing in the concession agreement refers to employees salaries as a factor that could be invoked to justify an EPA. Further, such salary increases are not prohibited by the agreement as a static salary level was never made a bidding instruction or assumption. Aside from the fact that the larger compensation packages/ increases have principally been given to executive officers (relative to the salary levles provided ordinary rank-and-file) , including their perks and benefits which are non-taxable, most employees were hired nine months ago which now places petitioners in estoppel. Petitioners cannot now complain about these salary levels. The above claim is also unacceptable especially in the light of recent massive retrenchments of MWSS employees as a consequence of the MWSS privatization. 7. ON THE FAILURE TO PUBLICLY DISCLOSE THE BIDDING INSTRUCTIONS AND BIDDING ASSUMPTIONS. In the bidding process, assumptions made by the Petitioners are not beyond their control. Petitioners must therefore assume the risk and consequences should certain assumptions not hold. If the assumptions were those of the previous MWSS, the petitioners accepted those assumptions and are therefore bound by those assumptions. The failure of the original MWSS and the Petitioners to publicly disclose bidding assumptions in a timely manner and in a language accessible to consumers display a cavalier attitude unresponsive to the public interest. A full understanding of the basis of the petitions before the Regulatory Office can only be obtained through access to all material information relevant. WHEREFORE, PREMISES CONSIDERED, OPPOSITORS PRAY THAT THE PETITION BE REJECTED ON ITS FACE DUE TO INSUFFICIENCY OF EVIDENCE TO ESTABLISH SIGNIFICANT ADDITIONAL COST AND THE FAILURE TO ESTABLISH FORCE MAJEURE THROUGH A SO-CALLED CONTINUING EL NINO. FURTHER, PETITIONERS HAVE NOT ESTABLISHED A CHANGE IN GOVERNMENT RULE, ORDER OR POLICY GOVERNING THE RELEASE OF WATER SUBJECT TO THE WATER LEVELS PREVAILING IN ANGAT AS SUCH IS A MATTER OF STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE . MANAGEMENT STUPIDITY AND INCOMPETENCE, CULPABILITY AND/OR CRIMINALITY SHOULD NOT AND CANNOT BE SUBSIDIZED BY WATER CONSUMERS THROUGH AN EXTRAORDINARY PRICE ADJUSTMENT. WE FURTHER PRAY THAT THE REGULATORY OFFICE USE THE OCCASION OF THE PETITION TO IMMEDIATELY PUT IN PLACE MEASURES TO ASSURE GREATER TRANSPARENCY AND MORE COMPREHENSIVE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT, ESPECIALLY IN THE LIGHT OF EXTREMELY INADEQUATE PUBLIC CONSULTATIONS CONDUCTED BY THE REGULATORY OFFICE ON THE WATER RATE INCREASE. THE PARTICIPATION OF CONSUMER GROUPS, ESPECIALLY URBAN POOR WOMENS' GROUPS, SHOULD HAVE BEEN PRO-ACTIVELY SOUGHT AS THEY ARE THE MOST VULNERABLE SECTORS THAT WOULD BE SEVERELY AFFECTED BY ANY INCREASE IN WATER RATES. WOMEN ARE DOUBLYBURDENED NOT ONLY AS WATER CONSUMERS BUT AS HOUSEHOLD FINANCIAL MANAGERS AMIDST ESCALATING PRICES OF ALL BASIC COMMODITIES, WHICH WOULD NOW INCLUDE WATER, IF PETITONERS' CLAIMS ARE TO BE GRANTED. Page 8 of 11 SIGNED: (MRS.) VIOLETA Q. PEREZ-CORRAL Manila Water Company Paying Consumer (Account No. 13-7950-1900-2) [Contact Tel. No. 371-5740] EARTH-SAVERS' MOVEMENT [Contact: Roger Birosel, Tel. No. 815 2689] TRADE UNION CONGRESS OF THE PHILIPPINES (TUCP) [Contact: Luis Corral, Tel. No. 433 8768 / Fax: 921 9758] ASSOCIATION OF PHILIPPINE ELECTRIC COOPERATIVES (APEC) [Contact: Rene Silos, Tel. No. 374 2601] cc: MWSS BOARD OF TRUSTEES [THRU: Mr. Reynaldo Vea, MWSS Administrator, Fax: 921 2887] MANILA WATER COMPANY [THRU: Mr. Virgilio C. Rivera, Regulatory Director, Fax: 928 5713 / 920 5288] MAYNILAD WATER SERVICES [THRU: Mr. Philip Cases, Corplan & Regulatory Affairs Manager, Fax: 920 5420] Page 9 of 11 ATTACHMENT B Mr. Fernando Z. Vicente Chief Regulator Regulatory Office MWSS Compound Balara, Quezon City May 29, 1998 RE: POSITION PAPER ON THE PETITION FOR AN EXTRAORDINARY PRICE ADJUSTMENT In the light of the petition of the private concessionaires for an Extraordinary Price Adjustment, the Freedom from Debt Coalition (FDC) respectfully submits its position and comments on the grounds and justifications raised by Manila Water Company, Inc.. and Maynilad Water Services, Inc. 1.) On the El Niño Phenomenon as a form of Force Majeure and as a cause to the increase in Capital Expenditures and Operating Expenses: FDC is in the position that the justification of EL Niño being a form of Force Majeure must be stricken down as it should have been incorporated into the bidding assumptions of the two concessionaires, considering that the phenomenon was foreseen to occur. It should not be the burden of the consumers to assume reckless and adventurous projections and conduct of business entities who did so with the objective of winning bids and sentiments of consumers. The Regulatory Office is likewise urged to look into the items pointed out by the concessionaires relating to the added operating and capital expenditures allegedly as a result of the El Niño phenomenon. As regards this point, the FDC would like to raise these questions: Should not all the items mentioned by the concessionaires, be part of normal business undertakings and must not constitute a ground or justification for an increase? b) How were these items utilized to address difficulties caused by the El Niño phenomenon? c) Maynilad Water applied the additional operating and capital expenditures from February to August of this year, what then is its basis for doing so, considering that the rainy season has already set in during the latter part of May? a) 2.) On the Devaluation of the Value of the Peso to the Dollar This cannot be used as a justification or a ground for an extraordinary price adjustment thereby passing entirely the burden and risks of the fluctuation of the foreign exchange rate to the consumers. As any business entity which is faced with normal business risks, the private concessionaires should have been prudent enough to assume that the peso-dollar rate will not remain at P26:$1 and should have appropriated such in their bidding assumptions. The Regulatory Office should determine the extent to which exchange rate fluctuations should be borne by private concessionaires, as well as the limit to which they may pass this burden on to the consumers. The assumed peso-dollar rate is a vital element of the concessionaire’s bidding assumptions, and they should be made to account for any errors they make in forecasting this. Again, the consumers cannot be made to pay for all the costs of running a business such as provision of water thereby freeing the capitalists of risks while at the Page 10 of 11 same time ensuring super profits. While it now appears that the two private concessionaires won their respective bids on the basis of erroneous assumptions, the Freedom from Debt Coalition maintains that, for the Regulatory Office to decide in favor of the petitions of the two private concessionaires, would be tantamount to a failure of the bidding process. To this end, therefore, all grounds and justifications mentioned which are either errors in the bidding price or errors in projections committed by the concessionaires must be stricken down and not be used as a basis for an extraordinary price adjustment. We urge the Regulatory Office to hear these points and we pray that that the petition of the two concessionaires be dismissed. Ma. Teresa Diokno-Pascual FREEDOM FROM DEBT COALITION Page 11 of 11