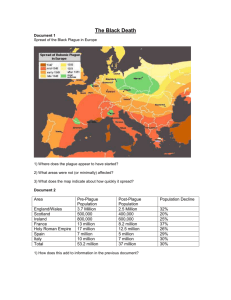

book - Cornell University

advertisement